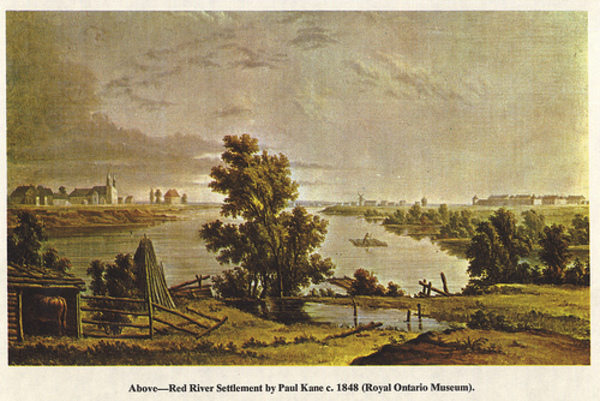

From the Red River Settlement to Manitoba (1812–70)

Source: Link

The year 2012 marked the bicentenary of the founding of the Red River settlement by Scotsman Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk. The settlement was able, with great difficulty, to take root and grow until it became part of Canada. In 1870, after a turbulent transition, the colony became Manitoba, the fifth Canadian province.

According to the terms of a royal charter issued in 1670, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) enjoyed exclusive commercial and settlement rights over Rupert’s Land, a vast territory that included the Red River region. The idea of establishing a community there was discussed by the company’s authorities in 1810, and the plan gained support. Then, in 1811, Selkirk, along with two partners (one of whom was John Halkett (Wedderburn)), acquired large interests in the HBC. Selkirk, who had dedicated a part of his fortune to launching settlements in Prince Edward Island and Upper Canada in previous years, wanted to help Highland Scots who had been dispossessed of their lands during the Highland clearances. He obtained a concession of a considerable area [see Maps] and an assurance that the HBC would cover the settlers’ transportation costs. In return, Selkirk undertook to establish an agricultural settlement while respecting certain conditions. For instance, retired HBC agents and their aboriginal or Métis wives (a French word meaning “mixed blood,” applied to those born to European fathers and aboriginal mothers or descendants of these marriages) would obtain a piece of land in the colony. As well, the fur trade, despite the fact that it could help sustain the settlers, would be forbidden so that it would not compete with the HBC’s monopoly.

The first contingent of settlers, comprising not only Scottish but also Irish men and women, arrived in Red River in 1812. They were followed two years later by a group of Scots from the Kildonan region. In 1815 about 300 people, the majority of whom were Roman Catholic, were living there. Some 40 French Canadian settlers, recruited by the colony’s first Catholic missionaries, settled in 1818, thereby increasing linguistic and cultural diversity.

The first decade of the colony’s existence was tumultuous. The hostility of the Nor’Westers, agents of the North West Company (NWC), a rival of the HBC that was active in Rupert’s Land despite the charter of 1670, exacerbated the challenges of establishing a settlement in a pioneer setting. The Nor’Westers included many Métis among their ranks, such as Cuthbert Grant. Other Métis were involved in supplying the NWC with foodstuffs, especially pemmican (dried meat, traditionally bison, sometimes mixed with berries). The NWC and the Métis saw the Red River settlement as a threat to their survival. The result was a violent conflict between the HBC on the one hand and the NWC and their Métis allies on the other; at stake was the control of the fur trade and supply networks in the northwest. Until the merger of the two companies in 1821, which put an end to the pemmican war, the settlers were periodically subjected to intimidation and harassment by the Nor’Westers and by their Métis allies, who were led by Grant. Twenty settlers lost their lives at Seven Oaks (Winnipeg) on 19 June 1816 [see Robert Semple].

The administration of the settlement passed from Selkirk’s estate (he had died in 1820) to the HBC in 1835. Until 1870 the company appointed the governors of the settlement and members of the Council of Assiniboia, who were responsible for assisting the governor. These authorities focused on attracting settlers, defending the territory, maintaining order, developing transport infrastructure, and keeping the settlement supplied. They also tried to preserve, to the extent that they could, the commercial monopoly of the HBC. Many inhabitants, including a large number of Métis, participated in the fur trade despite the company’s ban since the limited market for agricultural products in the isolated region forced the settlers to seek other forms of income. The HBC’s monopoly, which had been frequently denounced, finally came to an end in 1849 after the sensational trial of Pierre-Guillaume Sayer, who had been accused of illegal trading.

Over the next two decades Canadian, British, and American merchants and businessmen, such as Norman Wolfred Kittson, came to settle or invest in Red River. These new arrivals contributed to, among other things, the development of Winnipeg as an urban centre. At the end of the 1860s the economy was nevertheless still largely based on agriculture, partly because of the disappearance of the buffalo from the area and the scarcity of other animals, which upset hunting activities. About 600 Métis who were involved in the buffalo hunt and the trade of hides left Red River during the 1850s and 1860s and migrated further west towards the remaining herds, which subsequently became victims of overhunting [see Jules Decorby; Gabriel Dumont].

The population of the settlement grew from about 600 to 6,500 between 1821 and 1856, and to over 10,000 in 1870. After the arrival of some 170 Swiss recruited by Selkirk’s agents in 1821, the population increase was owing to natural growth as well as to retired HBC agents of European or Métis origin and their families. A large proportion of the inhabitants were francophone and anglophone Métis. Red River was one of the centres of Métis society and many of its leaders, including Cuthbert Grant, Charles Nolin, Pascal Breland, John Bruce, Gabriel Dumont, and Louis Riel, had been born or had homes there.

The settlement also included several dozen aboriginals who had been converted to Christianity. Other aboriginals frequented the Red River area to trade at the HBC posts while resisting the exhortations of Roman Catholic and Protestant missionaries (such as George-Antoine Bellecourt) who called not only for their religious conversion but also for their cultural assimilation. The number of aboriginals in the colony rose to a few hundred in the late 1860s, probably because of the scarcity of food resources and the increasing episodes of famine elsewhere in the northwest.

Communal infrastructure, including facilities for health and education, was gradually established in Red River [see Curtis James Bird; Marie-Louise Valade]. Simultaneously, the settlement’s arts and cultural life was sustained by musicians and poets such as Pierre Falcon. Information on the geography and the history of Red River and on the region’s flora and climate also began to appear [see Donald Gunn]. In 1859 the colony’s first newspaper was published [see Walter Robert Bown]. Nevertheless, living conditions remained difficult. Various measures were adopted to assist settlers who suffered from natural disasters or struggled with poverty. But floods, droughts, and grasshopper infestations still pushed many families to leave.

The settlement’s governance structure was, increasingly, the target of criticism during the 1850s and 1860s. Many residents resented the fact that the settlement was run by a private company, the HBC, and that its leaders and administrators were appointed, not elected. John Christian Schultz, for example, did not hesitate to describe the HBC regime as a “tyranny.” Three possibilities emerged from the discussions on the future of the settlement. Some wanted the settlement to be given the status of a British crown colony, independent from Canada; others, such as Schultz, wanted Red River to join the United Province of Canada (or, after 1867, the Dominion of Canada); and there were those who wanted the colony to be annexed to the United States, with which it already maintained close trade relations.

The fate of the colony had previously been met with relative indifference from united Canada. But from the 1850s onward there was a growing interest in expansion, particularly noticeable in Canada West (Upper Canada; present-day Ontario), and Red River became the object of special attention. The northwest gradually came to be seen as the natural extension of Canadian territory and as a vast space where settlement would stimulate economic growth. Two expeditions – one British, led by John Palliser, and the other Canadian, under the leadership of George Gladman, Henry Youle Hind, and Simon James Dawson – were organized in 1857 to further knowledge of the territory and confirm its agricultural potential. Their reports sparked enthusiasm and fed expansionist rhetoric. A few English Canadians who supported annexation settled in Red River after the expeditions concluded their work. The newcomers, as was the case with other settlers of British and Irish origin, held prejudices against the Métis, who made up 80 per cent of the settlement’s population at the end of the 1860s; they were particularly biased against the Franco-Catholic Métis. This hostility stirred up local tensions and raised concerns about respect for the rights of the Métis and their continued presence in the region.

Fearing northward American expansion, the British authorities, echoing some of the company’s former leaders, called upon the HBC [see Sir George Simpson] to negotiate the sale of Rupert’s Land, and therefore of the Red River settlement, to Canada. An agreement setting the date of the land transfer as 1 Dec. 1869 was signed without consulting local populations [see Sir George-Étienne Cartier]. The Canadian government did not formally guarantee that titles of ownership would be respected, which increased the fears of the settlement’s residents, since a large number of them had no official title to their lands. In September 1869 the Canadian authorities appointed William McDougall the first lieutenant governor of the territory. The nomination of such a strong supporter of expansionism, along with the arrival of a team responsible for surveying the colony’s land [see John Stoughton Dennis], precipitated events that led to the Red River rebellion.

On 11 Oct. 1869 a group of Métis headed by a young, educated, eloquent, and bilingual leader, Louis Riel, forced the team of surveyors to stop their work. At the beginning of the following month some Métis commanded McDougall to leave Red River and seized Upper Fort Garry (Winnipeg), an HBC trading post at the heart of the settlement. A provisional government, responsible for negotiating the terms of the colony’s annexation to Canada and ensuring that the rights of the local populations were respected, was established on 8 December; Riel became its president on 27 December. The composition of this representative government, which notably included Irish teacher William Bernard O’Donoghue [see The Fenians] as treasurer, reflected the ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity of the colony. On 3 March 1870 a Métis court martial condemned to death Orangeman Thomas Scott for insubordination. A man with an explosive temperament, Scott was contemptuous of the Métis. He had arrived at Red River the previous summer, when he joined John Christian Schultz and a group of others who attempted to overthrow the provisional government. Scott’s execution on 4 March sparked a storm of anger in Ontario directed at the Métis.

Negotiations with the Canadian authorities led to the provisional government’s ratification of the Manitoba Act on 24 June 1870. It met several demands, such as respect for land-ownership titles, provincial status, responsible government, bilingual institutions, and denominational schools [see Sir Wilfrid Laurier]. The creation of the province of Manitoba on 15 July [see Maps], did not, however, put an end to tensions. A Canadian–British military detachment that was officially in charge of maintaining peace, but partly composed of Ontario militiamen who wanted revenge for Scott’s execution, arrived at the end of August. Acts of intimidation and violence followed [see André Nault]. Elzéar Goulet, who had been a member of the court martial that condemned Scott, was killed. Fearing for his life, Riel fled to the United States. The new, bilingual lieutenant governor, Adams George Archibald, arrived on 2 September and established the first provincial government, composed of francophones and anglophones.

Despite the provisions of the Manitoba Act, thousands of Métis left the Red River area in the following years, either driven off their lands by a huge influx of settlers, mainly from Ontario, or relocating with the desire to be closer to the remaining buffalo herds so that they could continue hunting them and processing their hides. Many Métis migrated to the west, particularly to the territories of the present-day provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, where the fight for recognition of their rights led to the North-West rebellion and Riel’s execution in 1885. That year, the Métis formed only 7 per cent of the population of Manitoba.

Like all biographies in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography/Dictionnaire biographique du Canada, the biographies relating to the Métis in this thematic ensemble reflect the historiography of the time in which they were written. The majority of these articles were edited between 1960 and 1990. However, advances in research and the adoption of new perspectives since that period have led to a reconsideration of certain views and new debates on the development of Métis communities and their changing relationships with white populations. In particular, the question of whether the events of Seven Oaks should be described as a “battle” or a “massacre” remains a subject of passionate debate. A list of suggested readings about Métis history, with a particular focus on Red River, has been prepared to assist those interested in reading recent interpretations of the experiences of Métis Canadians.

The establishment of the Red River settlement is one of the pivotal events of the colonization of the Canadian west. We invite you to discover the community’s history, from its founding in 1812 to the creation of Manitoba in 1870, by reading the stories of men and women who were part of it.