Source: Link

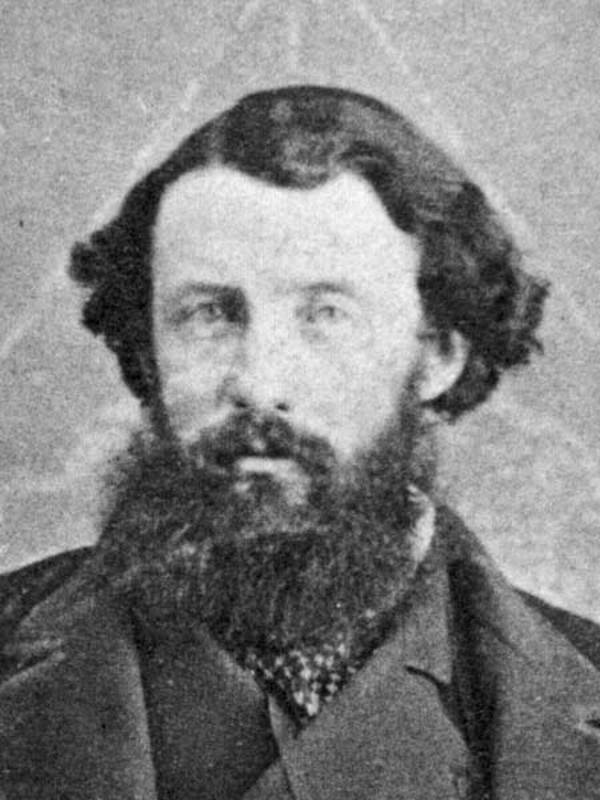

BOWN, WALTER ROBERT, dentist, businessman, journalist, publisher, politician, and office holder; b. 27 Jan. 1828, probably in Dorset, England; d. unmarried 8 March 1903 in Battle Creek, Mich.

Walter Robert Bown spent his early adult years in Brantford, Upper Canada, where his family was solidly middle class and his stepfather and brothers were leading citizens. Bown’s own prospects were not as promising; after some experience in commerce, he trained as a dentist, which in the mid 19th century was a calling but one step removed from that of barber. In order to improve his fortunes he left sometime around 1860 and moved to the western United States.

According to family sources, Bown served on the staff of a general of the Union army in the far west for several years. He also acted as a volunteer during the Sioux uprising of 1862–63 [see Tatanka-najin*]. Afterwards he practised dentistry, but also engaged in trade, which took on increasing importance during the mid 1860s. Working out of St Paul, Minn., and Pembina and Devil’s Lake (N.Dak.), he gradually became involved in commerce with the Red River settlement (Man.), first as a purveyor of vegetables through his firm, the International Vegitable House, and later as a fur trader in association with John Christian Schultz*.

It was Bown’s involvement with Schultz, dating from 1864, that propelled the diminutive dentist and trader to the forefront of affairs in Red River. Schultz, a highly controversial figure, introduced Bown to various business endeavours and, most important, to the politics of Canadian expansionism in the northwest and to anti-Hudson’s Bay Company rhetoric. During the next three decades Bown and Schultz were to be bound together to so great a degree that it was commonly accepted by both contemporaries and later historians that Bown was almost entirely the creature of Schultz.

Bown’s first direct brush with controversy came early in 1868 when Schultz, in jail for debt, was broken out by his wife, Agnes Campbell Farquharson. Acting as the editor of the Nor’Wester in Schultz’s absence, Bown portrayed the jailbreak as an action which had the support of the majority of Red River’s inhabitants, and which constituted a blow for freedom against the tyranny of HBC rule in general and its system of justice in particular. That this view was shared by only a handful of recent Canadian immigrants was soon demonstrated by a petition from 804 residents questioning the veracity of Bown’s assertions. When a delegation of these memorialists asked that their petition be inserted in the Nor’Wester, Bown refused, pleading a lack of paper. After being threatened with the seizure of the Nor’Wester’s plant and with forcible removal from the colony, he agreed to print 50 copies. An apparent misunderstanding concerning payment ensued. Bown publicly accused the two Métis who had picked up the printed petition with thievery, a charge which was met with a suit for defamation of character. Bown was convicted and briefly imprisoned when he failed to pay the costs and damages amounting to £14 19s. 6d.

The events of March to May 1868 strengthened Bown’s convictions concerning the impropriety of HBC rule, the company’s inability to control the settlement (the threats against him had been made in the presence of the governor of Assiniboia and Rupert’s Land, William Mactavish*), and the unfair nature of company-dominated courts. Thus, both he and Schultz redoubled their efforts to discredit HBC rule and to encourage annexation of Rupert’s Land to Canada, using the columns of the Nor’Wester to promote their views. They swore out affidavits in the United States attacking the judgement against Bown as “unlawful and offensive” and charging that the magistrates of Assiniboia were “owned and manipulated” by the HBC.

On 1 July 1868 Bown purchased the Nor’Wester from Schultz. He immediately moved the paper to larger quarters, improved the quality of its print, and made it into a weekly instead of a fortnightly publication. What he did not change was the paper’s politics. There were, however, times when the Nor’Wester served a purpose other than stirring up discord. During the late summer and fall of 1868, for example, Bown’s editorials raised awareness in St Paul and Canada of the plight of Red River settlers who were near starvation owing to a plague of grasshoppers and drought. At least partially because of his efforts as a journalist and as secretary of the Red River relief committee, enough food and seed were collected from Canada, the United States, and England to help the poorest settlers survive the winter of 1868–69.

By May 1869 the inhabitants of Red River had become aware that Rupert’s Land was soon to be annexed by Canada. While cognizant of the antipathy to the impending transfer of authority, Bown could scarcely credit the actions of the Métis in October and November 1869. He condemned the “French Half-Breed Insurrection” and in particular the blocking of lieutenant governor designate William McDougall’s entry into Red River, but he did not seem to realize how serious the resistance was until early in November when Métis leader Louis Riel* demanded that he use the Nor’Wester to print a public notice. Bown refused to cooperate, so Riel simply imprisoned him in his own office. Although Bown was later released, it was clear that the Nor’Wester could be commandeered whenever it suited Riel’s purpose.

Throughout November 1869 Bown remained active on behalf of the Canadian party, circulating petitions and publishing documents. By the following month Riel had had enough of Bown; he seized the Nor’Wester and sent men looking for its owner. Bown narrowly avoided capture and remained hidden at a remote HBC post north of the settlement until the end of the Métis resistance.

He was almost totally ruined by the events of 1869–70; his newspaper had been lost and his business as a commission agent for several Montreal houses had been badly hurt by his enforced absence. He returned to Ontario for several extended visits and there pleaded for speedy restitution of his “rebellion” losses. From late 1869 to early 1872 he was apparently dependent on the “bounty of friends” and relatives. Penury did not seem to lessen his taste for intrigue, however, for in March 1872 he accompanied Schultz to St Paul, where Riel was in hiding. The two men attempted to arrange for the theft of Riel’s personal papers, but the plot failed when the potential thieves informed Riel. Shortly thereafter Bown went to Ottawa, where his claims for losses were finally settled and the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald*, promised him a government job for the following year as “Storekeeper of the Surveys.”

Bown never again rose to the level of prominence which he had enjoyed in 1868–69, but he did not fade entirely from public view. Having befriended the fraudulent nobleman Lord Gordon Gordon* in 1872, he went about Winnipeg trying to clear Gordon’s name in the summer and fall of 1873. Later the same year, apparently in order to appease the so called Canadian “loyalists,” he was appointed to the Council of the North-West Territories [see Alexander Morris*]. By the mid 1870s his role had diminished to that of a mere servant in the interests of Schultz. Following the reorganization of the territorial council in 1876 he lost his position and thereafter devoted most of his time to looking after Schultz’s business affairs: at treaty payment time he would travel throughout the west, trading goods to natives; in Winnipeg he served as vice-president and general manager of Schultz’s North West Trading Company Limited; and he was Schultz’s partner in several real-estate speculations, some of which landed him in court. In 1888, when Schultz was named lieutenant governor of Manitoba, Bown became his private secretary, a post which he filled, despite failing health, until the end of Schultz’s term in September 1895.

This should have been the end of his life in the public eye but in October 1896 he was drawn back, under protest. Already in poor health and devastated by the recent death of his old friend Schultz, he had come to be dependent on Lady Schultz and was living under her care. Hearing of his circumstances, his twin sister, Mrs Ferrier, arrived in Winnipeg and quickly launched proceedings to have him declared a lunatic so that his financial affairs could be properly looked after. An embarrassing public hearing followed, during which Bown was found to be competent, on the testimony of several physicians, Archdeacon Robert Phair, and Lady Schultz. It was a sad victory for Bown. His health continued to deteriorate. Appropriately enough, when he died in 1903 he left his entire estate to Lady Schultz, for she and her husband had indeed been his surrogate family for the better part of 40 years.

NA, MG 26, A. PAM, ATG 25, file 72; MG 2, C14; MG 3, B11; B15; D; MG 12, E; MG 14, C66. Manitoba Morning Free Press, 21 Oct. 1896, 12 March 1903. Nor’Wester, 1859–69. Alexander Begg, History of the north-west (3v., Toronto, 1894–95). J. J. Hargrave, Red River (Montreal, 1871; repr. Altona, Man., 1977).

James David Mochoruk, “BOWN, WALTER ROBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bown_walter_robert_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bown_walter_robert_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | James David Mochoruk |

| Title of Article: | BOWN, WALTER ROBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |