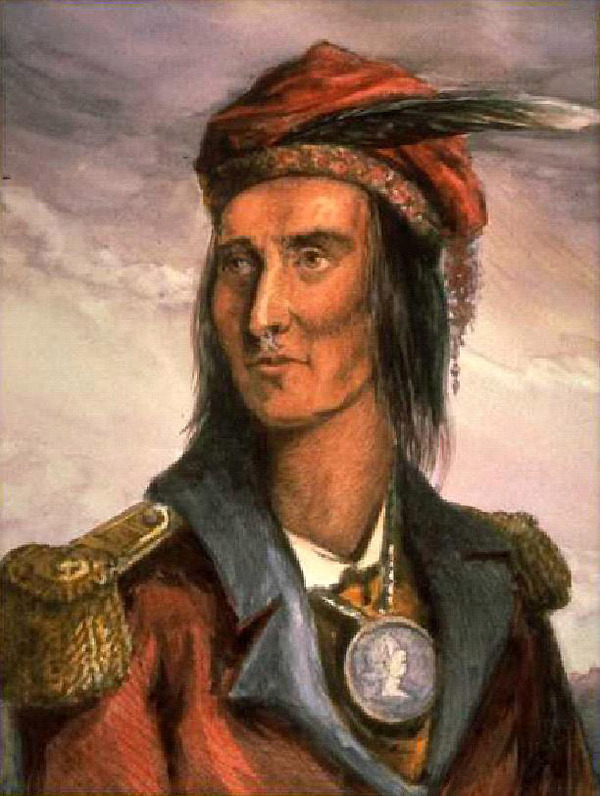

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

TECUMSEH (Tech-kum-thai), Shawnee chief; his name has been said to mean shooting star or panther crouching in wait; b. c. 1768, probably near present-day Springfield, Ohio; his father, who may have been named Puckeshinwa, was a Shawnee chief, and his mother may have had some Creek blood; d. 5 Oct. 1813 at what is now Thamesville, Ont., in the battle of Moraviantown.

During the closing decades of the 18th century, Indian lands west of the Appalachian Mountains were increasingly threatened by white colonization. The boundary that Great Britain had tried to erect by the Quebec Act of 1774 was shattered by the American revolution, and in the following years the Americans demonstrated their determination to extend their settlements at Indian expense. Efforts by Little Turtle [Michikinakoua] and others to unify the Six Nations and the various western tribes into a confederacy met with only limited success; the Americans dealt with individual tribes or parts of tribes and absorbed more and more land. Indian resistance to American expansion resulted in three major battles over the Ohio country during the 1790s. Many authorities claim that Tecumseh participated in all of them, but it appears that he was absent from the first. In the second, the defeat in 1791 of an American force near the Miamis Towns (Fort Wayne, Ind.), Tecumseh served as a scout with the warriors of the confederacy. In the third, the battle of Fallen Timbers (near Waterville, Ohio) in August 1794, he headed a small party of Shawnees and distinguished himself when other warriors were retreating by charging a group of Americans who had a field piece, cutting loose the horses, and riding off. Although Indian and American casualties were about the same in this battle, the Indians lost their hope of assistance from the British who, after apparent promises of aid, even refused them shelter in Fort Miamis (Maumee) following the battle. At the Treaty of Greenville in August 1795, the Indians gave up most of present-day Ohio and made other smaller cessions as well. They became caught in a vicious spiral. Scarcity of game and fur-bearing animals meant that to survive they were forced to sell more land to the whites and in so doing they grew even more dependent on them. Between 1803 and 1805 at least 30 million acres were relinquished. Moreover the American insistence on peace both with and among the various tribes weakened the foundations of the Indians’ warrior society.

For a few years after Fallen Timbers Tecumseh lived as a band chief at several locations near present-day Piqua, Ohio. He and his band then moved to the west fork of the White River (Ind.). In 1799 he took part in a council near what is now Urbana, Ohio, to smooth out differences between the races, presenting a speech of such “force and eloquence” that the interpreter had trouble translating it. At Chillicothe, Ohio, in 1803 he repeated assurances of peace after the murder of a settler. Two years later, Tecumseh and his band located at Greenville on the urgings of his brother the Prophet [Tenskwatawa*], who had been instructed by the Great Spirit to set up his headquarters there.

The millenarian religion preached by the Prophet was not unique. Throughout the world such movements have promised supernatural aid to native peoples faced with the realization that their way of life cannot be retained by physical strength alone. Like the leaders of the Delaware nativist revival in the 1750s and 1760s and the prophet of the ghost-dance religion on the prairies in the late 19th century, he predicted that divine intervention would save the Indians from their white oppressors. He taught that their present suffering was a chastisement. If they would purge themselves of white influence, stop practising witchcraft, and return to a purified Indian religion, the Great Spirit would see them live happily as before. There was also a thinly veiled hint that they would be delivered from the Americans, who “grew from the Scum of the great Water when it was troubled by the Evil Spirit.” “They are unjust,” the Great Spirit had told him, “they have taken away your Lands which were not made for them.” Stories of the Prophet’s revelations and commandments were soon in circulation all over the country south of the Great Lakes, along with accounts of his miracles. Some Delawares went so far in their fervour that they executed opponents of the movement. Whites at posts as distant as Michilimackinac (Mackinac Island, Mich.) complained of his influence.

There is no evidence that Tecumseh was involved in the evolution of this religion, but as Pontiac* had harnessed the energies of the Delaware revival, so Tecumseh transformed the Prophet’s religion into a movement dedicated to retaining Indian land. By the spring of 1807 he revealed a new firmness towards the Americans. When agent William Wells asked him to come to Fort Wayne for talks, Tecumseh replied: “The Great Spirit above has appointed this place for us, on which to light our fires, and here we will remain. As to boundaries, the Great Spirit above knows no boundaries, nor will his red people acknowledge any.”

Americans thought they detected the hand of Great Britain in the Indians’ activities. Governor William Henry Harrison of Ohio called the Prophet a “fool, who speaks not the words of the Great Spirit but those of the devil, and of the British agents.” He was unhappy that the Indians were still in the habit of calling on British posts to trade and to receive gifts from the king. He was also justly suspicious of the activities of Canadian-based traders who came gathering intelligence as well as furs. Indeed the governor-in-chief, Sir James Henry Craig, and lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, Francis Gore*, had set about revitalizing the Indian Department and recruiting Indian allies in the period of tension following the Chesapeake affair of 1807 [see Sir George Cranfield Berkeley]. In Craig’s view, “if we do not employ them, there cannot exist a moment’s doubt that they will be employed against us. . . .” Authorities sought out a few Indians who they thought could be trusted with the confidential information that war with the United States might not be far off. In return for support in such an event they were promised aid during the fighting and the eventual return of at least some of their lands. Apparently unaware of Tecumseh’s existence, the British were intrigued by stories of the Prophet. Craig suggested that his influence be purchased “at what might be a high price upon any other occasion.”

Attempts in 1808 to bring the Prophet to Fort Malden (Amherstburg), Upper Canada, failed because of enmity between him and the Shawnee chiefs visiting there and because he had been instructed by the Great Spirit to move to Tippecanoe (near Lafayette, Ind.). In June the unknown Tecumseh appeared in his place. Gore, who visited the fort in July, met Tecumseh and in a report to Craig called him “a very shrewd intelligent man.” The Shawnee chief had told Indian Department officials William Claus* and Matthew Elliott that he and the Prophet were attempting to gather all the tribes into one settlement to defend their lands. They had no intention at the moment of taking part in a war between Britain and the United States, although he added that “if their father the King should be in earnest and appear in sufficient force they would hold fast by him.” But though Tecumseh had made an impression, he was to be referred to for some time in British correspondence as the “Brother of the Prophet.”

In the spring of 1809 Tecumseh began a journey to the Senecas and Wyandots in the neighbourhood of Sandusky (Ohio) and to the Six Nations Indians in New York State to spread the message of unification against encroachment and to argue the case for common ownership of all Indian land. At Sandusky opposition from Tarhe (Crane), a Wyandot signatory to the Treaty of Greenville, prevented any move by Indians there. On his trip to the Six Nations, Tecumseh had with him as translator Caleb Atwater. According to Atwater, Tecumseh said he “had visited the Florida Indians, and even the Indians so far to the north that snow covered the ground in midsummer.” It is not clear if the statements were intended literally. This visit also brought no immediate results. Support for the confederacy continued to come from the tribes south of the Great Lakes and north of the Ohio River. It was strongest among the Potawatomis, Ojibwas, Shawnees, Ottawas, Winnebagos, and Kickapoos, but it could also be found among the Delawares, Wyandots, Menominees, Miamis, Piankeshaws, and others. It tended to come from young warriors, whereas older chiefs were more likely to be opposed, not the least of their reasons being the fact that the confederacy undermined their authority within their respective tribes. Blue Jacket [Weyapiersenwah] was one of the few older chiefs who remained consistently hostile to the Americans. All sorts of circumstances caused favour for the movement to ebb and flow. The degree of support among a tribe was probably linked to the level of frustration its people felt in their efforts to fend off the American advance and maintain an Indian way of life. On the other hand, some of the most militant adherents were drawn from tribes that had never considered themselves really defeated in previous clashes with the whites, whether French, British, or American. The effect of British agitation must also have been a factor in determining the amount of sympathy with which a group regarded the movement.

The confederacy was threatened with a loss of support later in 1809 when Governor Harrison, judging the organization, weak enough to be ignored, purchased another large tract from individual tribes. Tecumseh and the Prophet had promised to stop such transactions, and if they did nothing the movement would appear impotent. Direct action, however, would mean heavy loss of Indian life and withdrawal of British favour. Tecumseh responded therefore by preventing survey of the cession and by threatening death to those chiefs who had signed the treaty if the land were not returned. Tensions ran high, and in August 1810 Tecumseh went to Vincennes to meet with Harrison. He repeated the aims of the confederacy: the unification of the tribes and the establishment of the principle of common ownership of the land so that none of it could be sold without the consent of all Indians. He added that the village chiefs would be stripped of their powers and authority put into the hands of the warriors. The meeting solved nothing, and as fall approached war remained a distinct possibility.

In November Tecumseh was at Fort Malden where he suggested, to Elliott’s astonishment, that he was ready to go to war with the Americans. Elliott replied that he would lay the matter before the king; in fact, he wrote to Claus urgently requesting direction. His letter passed up the ladder to Craig, whose main concern was not setting a new policy but avoiding American retribution for his previous belligerent one. He instructed the British chargé d’affaires in Washington to warn the Americans that the Indians might attack. In February 1811, long after the Indians had gone to their hunting and sugaring grounds, he wrote to Gore ordering him to keep them peaceful by whatever means were available, including denial of arms and ammunition to those who appeared bellicose.

Tension between the Indians and the Americans continued to grow. Late in July Tecumseh, accompanied by some 300 Indians, arrived at Vincennes for talks with Harrison. Again nothing was solved, and on leaving Tecumseh told Harrison he was going to the south to spread the message of common ownership and unification to the Indians there. In anticipation of his absence Harrison began to plan a march on Tippecanoe in hopes of goading the Prophet to some rash, hostile act that would justify extermination or removal of his followers. When fighting did take place, on the morning of 7 November, casualties on both sides were about the same. The Indians ran out of ammunition and fled, their faith in the Prophet shaken, and the Americans looted and burned their village. Harrison mistakenly equated their disillusionment with the death of the movement. However, the relative strength of their resistance had shown the Indians that they did not have to rely on the supernatural alone to oppose the Americans. The sense of invincibility was perhaps gone, but a new determination to fight had been born.

When Tecumseh returned to Tippecanoe, he found “great destruction and havoc – the fruits of our labour destroyed,” the bodies of his friends lying in the dust, and his village in ashes. He began to rebuild his following and prepare for the eventual fight. By June 1812 it was clear that the confederacy was at least as strong as before Tippecanoe. Unaware that war between Britain and the United States had already been declared, Tecumseh boldly announced at Fort Wayne on 18 June that he was on his way to Fort Malden for lead and powder. Though he was warned by the Americans that his trip would be considered “an act of enmity,” no other attempt was made to stop him.

The extent of Tecumseh’s authority over the Indians who would fight alongside the British in the war is not easily defined. John Mackay Hitsman contends that he was “merely the most forceful of several tribal chiefs,” and certainly there were other prominent leaders present on the Detroit frontier, Roundhead [Stayeghtha], Myeerah, Thomas Splitlog [To-oo-troon-to-ra*], and Billy Caldwell* among them. The evidence suggests, however, that the only person who rivalled Tecumseh in his ability to marshal Indian support for the war effort was Robert Dickson*, a Scottish trader from the upper Mississippi valley. Matthew Elliott reported: “Tech-kum-thai has kept . . . [the Indians] faithful – he has shewn himself to be a determined character and a great friend to our Government.” It should not be thought, however, that Tecumseh had any sort of absolute control over the Indians who had followed him into Upper Canada. What authority he had had before the war was badly damaged by their loss of faith in the Prophet’s teachings. But no Indian leader had ever been able to dictate to the warriors. White officers had that kind of authority because white societies were able to carry on despite huge losses in battle. The Indians could not sustain such losses; the continued existence of a tribe depended on its having enough young men to hunt and fight, and it was left to the individual warrior to make the decision about his own survival in war. White officers found the practice made Indians unreliable, in their terms, and they strongly disapproved. Nor did they ever come to understand the Indian habit of deciding to fight or not to fight on the basis of omens and visions and dreams. The fact that some Indians were not above using visions to extort special favours from their allies made relations worse. Tecumseh was different. There is no record of his having used such tactics with the British, and they liked working with him because he seemed to understand military operations as if he were a trained soldier.

The first official word of Tecumseh’s presence in Upper Canada after the outbreak of the war came on 8 July: he was reported to have played “a conspicuous part” in a council at Sandwich (Windsor) the day before. On 13 July the American forces under Brigadier-General William Hull, governor of the Michigan Territory, seized that village. Then, encouraged by desertions among the Upper Canadian militia and the apparent neutrality of Indians he had expected to support the British, Hull began to send detachments farther into the province. He was fearful, however, that Indians might cut his lines of supply, which ran south by land to Ohio, and indeed on 5 August one of his provision trains was ambushed in the neighbourhood of Brownstown (near Trenton, Mich.) by Tecumseh and some others. This action, combined with the news that the British had captured Fort Michilimackinac [see Charles Roberts] and were advancing from the Niagara frontier, prompted Hull’s withdrawal of most of his forces from Canadian territory on 8 August. The next day Tecumseh and Roundhead led the Indians who joined some regulars and militia in a bloody skirmish south of Detroit at Maguaga (Wyandotte) with an American force sent out to protect another supply train. Isaac Brock, the British commander in Upper Canada, reached Fort Malden with reinforcements on 13 August and immediately formulated a bold plan for an attack on Detroit. Tecumseh was delighted, since the Indians, about 600 in number, had been fretting at British caution. On 16 August Brock advanced on the fort, having threatened Hull that “the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond controul the moment the contest commences.” The American commander surrendered without a fight. Legend has it that Tecumseh rode beside Brock when he entered Detroit and that Brock gave him his sash as a mark of respect. Whatever the case may be, there is no doubt of Brock’s esteem for him. “A more sagacious or a more gallant Warrior does not I believe exist,” the commander wrote. Moreover, Brock became convinced that an Indian state south of the Great Lakes should be created.

In the early weeks of the war many Indians stood aside from the fighting, remembering broken promises of British aid and feeling the odds against the confederacy too great. The successes of the British at Detroit and Michilimackinac, however, created the impression that they were willing and able to take American territory in this war, and the Potawatomi capture of the garrison from Fort Dearborn (Chicago) on 15 August gave the Indians a new self-confidence. Hundreds of them abandoned their neutrality. By the autumn of 1812 Tecumseh had about a thousand warriors with him.

Tecumseh’s whereabouts during the winter of 1812–13 are not clear. Some authorities claim he travelled south again, but the sole notice in primary sources says simply that he was ill for part of the season. When spring came, the British began an offensive out of Fort Malden into the country south of Lake Erie. In April Tecumseh and Roundhead led about 1,200 Indians who joined with some 900 regulars and militia under Major-General Henry Procter* in the siege of Fort Meigs (near Perrysburg, Ohio). The American garrison, which numbered about a thousand, resisted successfully but a relief force was attacked and 500 prisoners were taken. The Indians, carried away with their triumph, began to kill them, and Procter made no effort to stop the slaughter, which ceased only with the arrival of Tecumseh. Indeed, Tecumseh’s humanity on this occasion was long remembered and it contributed to his reputation among whites. The Indians were eager to have this fort taken, and after the first siege failed Tecumseh and the others put such pressure on Procter that a second was undertaken in July. The British committed only a few regulars to the attack, depending on the Indians, whose numbers had been augmented from a force of some 1,400 that Robert Dickson brought to Fort Malden from the upper country. Tecumseh and Matthew Elliott began by leading a scouting party eastward to check for approaching reinforcements. The British did not have proper siege equipment with them, and the Indians were apparently relying on a sham battle to draw the garrison out of the fort; so when the trick failed, the operation was abandoned. Procter then chose Fort Stephenson (Fremont, Ohio) as a more vulnerable target, but it too resisted fiercely when besieged at the end of July. Morale among the British and the Indians flagged as a result of the heavy casualties suffered there.

The situation on the Detroit frontier worsened with the defeat of the British fleet under Captain Robert Heriot Barclay* at the battle of Put-in Bay (Ohio) on 10 September. Procter, with about 1,000 regulars and nearly 3,000 warriors and their dependents, had no way now to obtain sufficient provisions, and he knew that the Americans under William Henry Harrison were preparing an invasion. Without consulting the Indians he began dismantling Fort Malden and preparing to retreat towards the head of Lake Ontario. Tecumseh had long suspected that Procter would flee without a fight and he begged him to provide the Indians with arms so that they could carry on their struggle alone. Their goal of retaining their homeland could hardly be achieved from the Niagara frontier. Procter promised to make a stand at the forks of the Thames (Chatham), and some of the Indians, including Tecumseh, agreed to make the retreat. Tecumseh repeatedly urged Procter to stop and face the enemy, but even when the promised location for a fight was reached Procter continued on ahead of the main force, looking for a more defensible site. A number of Indians, believing no stand would be taken, left in disgust. Tecumseh was apparently infuriated by the general’s behaviour but was unable to find him.

Finally, on 5 October, Procter met the Americans, in the battle of Moraviantown, not far from the village that missionary David Zeisberger had founded in 1792 for converts fleeing the disorder on the American frontier. The British formed their lines with the Indians stationed in swampy ground on the right. The troops were so demoralized that at the first American attack they broke and ran. Their flight left about 500 Indians to face some 3,000 Americans. During this futile resistance Tecumseh was fatally wounded. To this day neither the identity of his slayer nor what his comrades did with his remains is known. With his death, effective Indian resistance south of the lakes practically ceased. Little more than a week later some of the tribes represented at the battle signed a truce with the Americans. Various efforts by the British to re-enlist them failed. By July 1814, months before the end of the war, Harrison met with more than 3,000 Indians to outline his conditions for peace. Neither those talks nor the Treaty of Spring Wells (1815) demanded new land cessions. By 1817, however, the Americans had returned to their old policy. In that year, except for a few left on small reserves, the Indians were removed from Ohio. By 1821 the native inhabitants of Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan had met the same fate. A small number of the displaced came to Upper Canada but most were gradually pushed westward. Of Tecumseh’s confederacy nothing remained. Ottawa chief Naywash (Neywash) pronounced its epitaph in 1814 when he said, “Since our Great Chief Tecumtha has been killed we do not listen to one another, we do not rise together. We hurt ourselves by it. . . .” Tecumseh’s enemy, Harrison, had described him in 1811 as “one of those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions.” The revolution had been crushed.

Tecumseh’s struggle and death have haunted the imagination of poets in Canada until the present day. To George Longmore, in his “Tecumthé; a poetical tale, in three cantos” (1824), he was a tragic hero, whose flaw was that he was swayed by “nature not reason.” John Frederick Richardson* in his poem Tecumseh, or the warrior of the west (1828) depicted Tecumseh in a similar manner, the personification of goodness and humanity transformed into a savage fiend by the Americans’ murder of his (imaginary) son. In 1886 Charles Mair* published a long verse-drama, Tecumseh, in which the Shawnee chief is again the tragic and romantic hero, and in, his alliance with the British and his opposition to American expansionists is a symbol of the dual aims of the Canada First movement. An analogy is made in Bliss Carman*’s “Tecumseh and the eagles” (1918) with the struggle of nations for freedom in World War I. In Don Gutteridge’s Tecumseh (1976) the hero is a potential mediating figure between Indian and white cultures, whose vision, like the poet’s, is to “weave a new history from our twin beginnings.”

Over the course of the 19th century, historians writing in Upper Canada about the War of 1812 made him into one of its heroes, until he had a place in the mythology alongside Brock, Laura Secord [Ingersoll*], and the Canadian militia. To historian David Thompson he was simply “that great aboriginal hero.” To Richardson and Gilbert Auchinleck he was the noble savage, “ever merciful and magnanimous,” of a “gallant and impetuous spirit,” eloquent, high-minded, and dignified. The fact that he died fighting while a British general retreated before the invading Americans enhanced his appeal to the loyalist mind. The worshipful approach that these tastes inspired had two serious consequences. It encouraged the uncritical embellishment of Tecumseh’s image with pieces of hearsay and invention, and it discouraged consideration of his motives. Late in the century Ernest Alexander Cruikshank* broke with the tradition and for the first time Tecumseh’s war service was subjected to a scholarly analysis of the records. Historical writers of a lesser stature have, however, perpetuated and extended the old interpretation. In 1910 Katherine B. Coutts wrote, “Of his great gifts he gave all in the Canadian cause.” It was and is impossible to cast Tecumseh as a Canadian patriot first and an Indian second. His loyalty was never to Canada or even to the British in Canada. It was to a dream of a pan-Indian movement that would secure for his people the land necessary for them to continue their way of life. The few months he spent fighting with the British forces were in service of that vision. In his failure and death the cynical British and Canadians were only slightly less his enemies than the Americans.

[Until recently it was thought that Levi Adams had written “Tecumthé; a poetical tale, in three cantos,” which appeared in the Canadian Rev. and Literary and Hist. Journal (Montreal), 2 (1824): 391–432. Mary Lu MacDonald’s introduction to The charivari, or Canadian poetics (Ottawa, 1977), 3–10, however, established George Longmore as its author.

The portrait of Tecumseh most likely to be an accurate representation of him is the one drawn in 1808 by trader Pierre Le Dru. The evidence for its authenticity is circumstantial: Le Dru also did a sketch of the Prophet at this time, and his drawing bears a strong resemblance to a later painting of the Prophet done from life by George Catlin. If Catlin’s Prophet and Le Dru’s Prophet are the same man, then there is a good chance that Le Dru’s Tecumseh is also a good likeness. The sketch of Tecumseh that appears in B. J. Lossing, The pictorial field-book of the War of 1812 . . . (New York, 1869), and is reproduced in James Mooney, “The ghost-dance religion and the Sioux outbreak of 1890,” Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Annual report (Washington), 1892–93, pt.2, 1896, is a composite, the head being taken from the Le Dru work and the shoulders from a probably unauthentic drawing by an unknown artist. h.c.w.g.]

Fort Maiden National Hist. Park Arch. (Amherstburg, Ont.), Information files, Tecumseh. National Arch. (Washington), RG 75, M15. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 114: 74–82; MG 19, A3; F1; F2; RG 8, I (C ser.), 257: 211, 217; 678: 267; 682: 101; RG 9, I, B1; B3; RG 10, A1; A2; A6. PRO, CO 42/89, 42/146–52, 42/160, 42/165; FO 5/48, 5/61–62, 5/77, 5/84, 5/87, 5/92, 5/112. Wis., State Hist. Soc., Draper mss, ser.YY. Anthony Wayne . . . the Wayne–Knox–Pickering–McHenry correspondence, ed. R. C. Knopf (Pittsburgh, Pa., 1960; repr. Westport, Conn., 1975). Corr. of Hon. Peter Russell (Cruikshank and Hunter). Corr. of Lieut. Governor Simcoe (Cruikshank). Diplomatic correspondence of the United States: Canadian relations, 1784–1860, comp. W. R. Manning with M. A. Gillis (4v., Washington, 1940–45), 1. Documents relating to the invasion of Canada and the surrender of Detroit, 1812, ed. E. A. Cruikshank (Ottawa, 1912). Fort Wayne, gateway of the west, 1802–1813: garrison orderly books, Indian agency account book, ed. and intro. B. J. Griswold (Indianapolis, Ind., 1927; repr. New York, 1973). George Rogers Clark papers . . . [1771–84], ed. J. A. James (2v., Springfield, Ill., 1912–26). J. [E. G.] Heckewelder, Narrative of the mission of the United Brethren among the Delaware and Mohegan Indians, from its commencement, in the year 1740, to the close of the year 1808 . . . (Philadelphia, 1820; repr. [New York], 1971). William Hull, Memoirs of the campaign of the north western army of the United States, A.D. 1812, in a series of letters addressed to the citizens of the United States . . . (Boston, 1824). J. D. Hunter, Manners and customs of several Indian tribes located west of the Mississippi . . . (Philadelphia, 1823; repr. Minneapolis, Minn., 1957). Indian affairs: laws and treaties, comp. C. J. Kappler ([2nd ed.], 2v., Washington, 1904). John Johnston, “Recollections of sixty years,” ed. C. R. Conover, in L. U. Hill, John Johnston and the Indians in the land of the Three Miamis . . . (Piqua, Ohio, 1957), 147–92. Letter book of the Indian agency at Fort Wayne, 1809–1815, ed. Gayle Thornbrough (Indianapolis, 1961). The life and correspondence of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, K.B., ed. F. B. Tupper (2nd ed., London, 1847). Richard M’Nemar, The Kentucky revival; or, a short history of . . . Shakerism . . . (New York, 1846; repr. 1974). [Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak], Black Hawk, an autobiography, ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana, Ill., 1964). Humphrey Marshall, The history of Kentucky . . . (2nd ed., 2v., Frankfort, Ky., 1824). Memoirs and correspondence of Viscount Castlereagh, second Marquess of Londonderry, ed. C. [W. Stewart] Vane (12v. in 3 ser., London, 1848–53). Messages and letters of William Henry Harrison, ed. Logan Esarey (2v., Indianapolis, 1922). Mich. Pioneer Coll. The new American state papers [1789–1860], Indian affairs, ed. T. C. Cochran (13v., Wilmington, Del., 1972). Outpost on the Wabash, 1787–1791; letters of Brigadier-General Josiah Harmar and Major John Francis Hamtramck . . . , ed. Gayle Thornbrough (Indianapolis, 1957). [John Richardson], Richardson’s War of 1812; with notes and a life of the author, ed. A. C. Casselman (Toronto, 1902; repr. 1974); War of 1812 . . . ([Brockville, Ont.], 1842). The St. Clair papers . . . , ed. W. H. Smith (2v., Cincinnati, Ohio, 1882). Select British docs. of War of 1812 (Wood). Tecumseh: fact and fiction in early records, ed. C. F. Klinck (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1961). The territorial papers of the United States, comp. C. E. Carter and J. P. Bloom (28v. to date, Washington, 1934– ; repr. vols. 1–26 in 25v., New York, 1973). U.S., Congress, American state papers (Lowrie et al.), class II, vols.[1–2]. Kentucky Gazette (Lexington, Ky.), 1807–12. National Intelligencer (Washington), 1807–12. Quebec Gazette, 1807–12. Western Sun (Vincennes, [Ind.]), 1807–12. Caleb Atwater, A history of the state of Ohio, natural and civil (Cincinnati, 1838); The writings of Caleb Atwater (Columbus, Ohio, 1833). Gilbert Auchinleck, A history of the war between Great Britain and the United States of America, during the years 1812, 1813, and 1814 (Toronto, 1855). Pierre Berton, Flames across the border, 1813–1814 (Toronto, 1981); The invasion of Canada, 1812–1813 (Toronto, 1980). [These two works perpetuate the romantic and spectacular view of Tecumseh. h.c.w.g.] H. M. Brackenridge, History of the late war, between the United States and Great Britain; containing a minute account of the various military and naval operations (4th ed., Baltimore, Md., 1818). C. W. Butterfield, History of the Girtys . . . (Cincinnati, 1890). G. C. Chalou, “The red pawns go to war: British-American Indian relations, 1810–1815” (phd thesis, Indiana Univ., Bloomington, 1971). Moses Dawson, A historical narrative of the civil and military services of Major-General William H. Harrison . . . (Cincinnati, 1824). J. B. Dillon, A history of Indiana from its earliest exploration by Europeans to the close of the territorial government, in 1856 . . . (Indianapolis, 1859; repr. [New York], 1971). R. C. Downes, Council fires on the upper Ohio: a narrative of Indian affairs in the upper Ohio valley until 1795 (Pittsburgh, 1940). Benjamin Drake, Life of Tecumseh, and of his brother, the Prophet . . . (Cincinnati, 1841). [Still the most reliable secondary source. h.c.w.g.] Dennis Duffy, Gardens, covenants, exiles: loyalism in the literature of Upper Canada/Ontario (Toronto, 1982). N. W. Edwards, History of Illinois, from 1778 to 1833; and life and times of Ninian Edwards (Springfield, Ill., 1870; repr. New York, 1975). Edward Eggleston and Lillie Eggleston Seelye, Tecumseh and the Shawnee Prophet . . . (New York, 1878). E. S. Ellis, The life of Tecumseh, the Shawnee chief . . . (New York, 1861). Timothy Flint, Indian wars of the west . . . (Cincinnati, 1833; repr. [New York], 1971). W. A. Galloway, Old Chillicothe: Shawnee and pioneer history; conflicts and romances in the Northwest territory (Xenia, Ohio, 1934). H. C. W. Goltz, “Tecumseh, the Prophet, and the rise of the Northwest Indian Confederation” (phd thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1973). N. St C. Gurd, The story of Tecumseh (Toronto, 1912). H. S. Halbert and T. S. Ball, The Creek war of 1813 and 1814 (Chicago, 1895). W. H. Harrison, A discourse on the aborigines of the Ohio valley . . . (Chicago, 1883). History of Greene County, together with historic notes on the northwest, and the state of Ohio . . . , comp. R. S. Dills (Dayton, Ohio, 1881). Hitsman, Incredible War of 1812. Reginald Horsman, Expansion and American Indian policy, 1783–1812 ([East Lansing, Mich.], 1967); Matthew Elliott. T. L. M’Kenney and James Hall, History of the Indian tribes of North America, with biographical sketches and anecdotes of principal chiefs . . . (3v., Philadelphia, 1838–44). Leslie Monkman, A native heritage: images of the Indian in English-Canadian literature (Toronto, 1981). J. M. Oskison, Tecumseh and his times: the story of a great Indian (New York, 1938). Bradford Perkins, Prologue to war: England and the United States, 1805–1812 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, Calif., 1961; repr. 1963). E. T. Raymond, Tecumseh: a chronicle of the last great leader of his people (Toronto, 1915). David Thompson, History of the late war, between Great Britain and the United States . . . (Niagara [Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.], 1832; repr. [New York], 1966). Glenn Tucker, Tecumseh: vision of glory (Indianapolis and New York, 1956). [Contains much apocryphal material. h.c.w.g.] K. B. Coutts, “Thamesville and the battle of the Thames,” OH, 9 (1910): 20–25. E. A. Cruikshank, “The ‘Chesapeake’ crisis as it affected Upper Canada,” OH, 24 (1927): 281–322; “The employment of Indians in the War of 1812,” American Hist. Assoc., Annual report (Washington), 1895: 319–35. Reginald Horsman, “American Indian policy in the old northwest, 1783–1812,” William and Mary Quarterly (Williamsburg, Va.), 3rd ser., 18 (1961): 35–53.

Herbert C. W. Goltz, “TECUMSEH (Tech-kum-thai),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tecumseh_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tecumseh_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Herbert C. W. Goltz |

| Title of Article: | TECUMSEH (Tech-kum-thai) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |