Source: Link

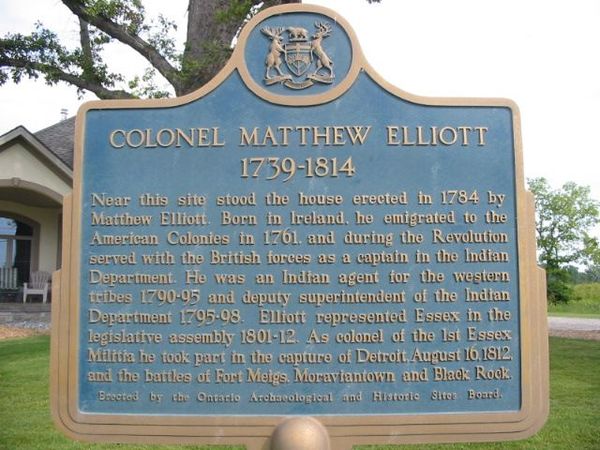

ELLIOTT, MATTHEW, farmer, Indian Department official, politician, and militia officer; b. c. 1739 in County Donegal (Republic of Ireland); d. 7 May 1814 at what is now Burlington, Ont.

Matthew Elliott came to North America in 1761 and settled in Pennsylvania. During Pontiac*’s uprising he served as a volunteer in Colonel Henry Bouquet’s forces, going with him to the relief of Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh, Pa) in 1763 and against the Indians of the Ohio country the following year. In the decade before the American revolution Elliott traded among the Shawnees on the Scioto River, in what is now Ohio. In 1774 he was the emissary for the Shawnees who met Lord Dunmore, the governor of Virginia, when he advanced into the Ohio country. On the eve of the revolution Elliott was the partner of Alexander Blaine of Carlisle, Pa. He continued to trade in the Ohio region during the winter of 1775–76, and in the summer of 1776 acted as an American emissary to invite the Shawnees and Delawares to a treaty at Fort Pitt. He kept this episode secret later in his life when he became a loyalist.

During the winter of 1776–77 Elliott again journeyed to the Shawnee towns, and in the spring he visited British-held Detroit in an attempt to regain goods stolen from him by Senecas. Arrested as a suspected American spy, he was sent to Quebec but was soon allowed to return to Pittsburgh on parole. He arrived there in early 1778. Apparently feeling he had little to gain by staying, in March he fled to Detroit along with Alexander McKee* and Simon Girty. He served as a scout on Henry Hamilton*’s expedition to Vincennes (Ind.) in the autumn of 1778 but left before Hamilton was captured by the Americans in February 1779. For the remainder of the revolution Elliott served as a British Indian agent. He saw action at the defeat of American captain David Rodgers on the Ohio in the summer of 1779 and during Captain Henry Bird’s expedition against Kentucky in 1780. The next spring he accompanied a band of warriors into Kentucky once again. Later in the year he headed the party that forcibly removed from their homes a colony of Indians converted by the Moravians and settled along the Muskingum (Tuscarawas) River (Ohio) [see Glikhikan*]. These Indians had on an earlier occasion saved Elliott’s life, but he brought along some trade goods, intending to buy up their cattle for a few dollars each and sell them at high prices in Detroit; the possibility of a quick profit was never far from his thoughts. In 1782 he fought near present-day Upper Sandusky, Ohio, in the defeat of American colonel William Crawford and again at Blue Licks (near Cowan, Ky).

After the revolution Elliott established himself on a farm at what later became Amherstburg, Upper Canada. His home developed into a show-place in the region; he eventually owned over 4,000 acres and many slaves, a number of whom he had acquired in the course of raids during the revolution and refused to relinquish despite government pressure. In partnership with William Caldwell* he renewed his trading activities, dealing with the Indians South of Lake Erie and bringing flour, cattle, bacon, and other provisions from Pittsburgh to sell at Detroit as well. But it was becoming increasingly difficult to do business in that disputed area and the firm went bankrupt in 1787. In spite of this misfortune and the handicap of illiteracy, Elliott became a justice of the peace for the new District of Hesse in 1788.

Elliott continued to encourage the Shawnees to oppose the American advance across the Ohio River, and in 1790 he became assistant to McKee, who was Indian superintendent at Detroit. Along with McKee, in the early 1790s Elliott helped organize the various tribes to resist American military expeditions and refuse American requests for land cessions. His main area of operations was along the Miamis (Maumee) River. Much of his time was spent in distributing British supplies to the Indians, a necessity if the warriors were to stay assembled, and it is likely that he went beyond official British policy in his efforts to strengthen their resistance. Elliott was present at the battle of Fallen Timbers in August 1794, but as an observer not as a participant; the British chose not to support the Indians militarily and the Indian forces were crushed.

Meanwhile, earlier in the decade Elliott had made amends for his harsh treatment of the Moravians and their converts, first by allowing them to take refuge on his farm and then, because they wished to be at a distance from the corrupting influences of the white community, by arranging for them to settle near what is now Thamesville, Ont. [see David Zeisberger]. He even attended the service at their meeting-house on Christmas Day 1791.

In the summer of 1796 Elliott became “superintendent of Indians and of Indian Affairs for the District of Detroit,” but he was suspected of peculation and was involved in clashes with the military authorities. In December 1797 he was dismissed. The Indian Department was traditionally careless in its accounting and secretive about its business, and Elliott appears to have been about as honest as the average officer. He had been accustomed to working in an atmosphere of crisis, and after that atmosphere evaporated following the signing of Jay’s Treaty in 1794, he failed to adapt to the more orderly practices of peace-time administration. During the next ten years he made considerable efforts to secure reinstatement. He even travelled to England in 1804, but his efforts failed despite recommendations by Sir John Johnson*, superintendent general of Indian affairs, and David William Smith*, former speaker of the Upper Canadian House of Assembly. His farm, however, was prospering. In 1796 one traveller, Isaac Weld*, described it as “cultivated in a style that would not be thought meanly of even in England.” From 1800 to 1804 he was a member of the House of Assembly, attending regularly and participating actively in the proceedings. He was re-elected in 1804 and 1808 but attended less frequently because of other business. On several occasions he appeared before authorities at York (Toronto) on behalf of groups of his constituents who were seeking land grants.

When after 1807 another crisis erupted in British-American relations, the great importance of Elliott’s influence among the Indians was recognized. In the spring of 1808 he was reappointed superintendent in place of Thomas McKee, Alexander’s son. During the years preceding the War of 1812 he helped persuade the Indians within American territory to join the British in the event of war, supplied them with provisions, and encouraged the confederacy being organized by the Shawnee Tecumseh and his brother the Prophet [Tenskwatawa*] for the purpose of resisting American encroachments on Indian lands. In the war itself he was actively in the field, leading the Indian allies of the British and bearing the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the Essex County militia. He was present in August 1812 at the taking of Detroit from the Americans and the next month accompanied the Indians on Major Adam C. Muir’s abortive expedition against Fort Wayne (Ind.). In order to ease the pressure on provisions at Detroit, Elliott led a large number of Indians to winter at the rapids of the Miamis River (Maumee, Ohio), where the Americans had abandoned supplies of corn and cattle. In 1813 he was at the battle of Frenchtown and the sieges of Fort Meigs (near Perrysburg, Ohio) and Fort Stephenson (Fremont, Ohio). The British commander, Henry Procter*, blamed him for failing to prevent the Indians from killing American prisoners, and it is possible that Elliott, being over 70 and having lost his son Alexander in the war, did not make every effort; however, the warriors in their growing bitterness were more and more inclined to take revenge on the Americans who were driving them from their lands. In the autumn he was with the Indians who covered Procter’s retreat and who fought with desperation in the battle of Moraviantown. During the last months of his life his base of operations was the Burlington area and in the winter of 1813–14 he led the Indians in raids on the Niagara frontier. He became ill and died on 7 May, after almost half a century’s experience of border warfare.

Elliott for many years had lived with a Shawnee woman, and she was the mother of Alexander and of Matthew, who was active among the Shawnees in the Amherstburg region for many years. In 1810 Elliott married young Sarah Donovan, and they had two sons, Francis Gore and Robert Herriot Barclay. Perhaps influenced by some “ungentlemanly remarks” of Elliott’s, an American prisoner whom he had ransomed from the Indians about 1793 left the following description of his rescuer: “Elliott’s hair was black, his complexion dark, his features small; his nose was short . . . turning up at the end, his look was haughty, and his countenance repulsive.” Throughout his career Elliott was always willing, and often able, to turn any situation to his own advantage, but he was also effective in maintaining British influence among the Indians along the borders of Upper Canada.

An extensive bibliography on Elliott is contained in Reginald Horsman, Matthew Elliott, British Indian agent (Detroit, 1964). Particularly useful sources include the following: BL, Add. mss 21661–892 (transcripts at PAC). Carnegie Library (Pittsburgh, Pa.), George Morgan, letter books, 1775–79. DPL, Burton Hist. Coll., John Askin papers; Solomon Sibley papers. Pa., Hist. Soc. (Philadelphia), Yeates family papers, corr, 1762–80. PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q; MG 19, F1; RG 1, E3, 12–13; RG 4, B17, 13–14; RG 8, I (C ser.); RG 10, A1, 1–4; A2, 8–12. PRO, AO 12/40, 12/66, 12/109. Corr. of Hon. Peter Russell (Cruikshank and Hunter). Corr. of Lieut. Governor Simcoe (Cruikshank). Frontier defense on the upper Ohio, 1777–1778 . . . , ed. R. G. Thwaites and L. P. Kellogg (Madison, Wis., 1912; repr. Millwood, N.Y., 1973). J. [E. G.] Heckewelder, Narrative of the mission of the United Brethren among the Delaware and Mohegan Indians, from its commencement, in the year 1740, to the close of the year 1808 . . . (Philadelphia, 1820; repr. [New York], 1971), 232–36, 244–45, 276–77. Mich. Pioneer Coll., 9 (1886), 10 (1886), 12 (1887), 15 (1889), 20 (1892), 23 (1893), 24 (1894), 25 (1894). Isaac Weld, Travels through the states of North America, and the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (London, 1799), 343–59. Windsor border region (Lajeunesse). [David Zeisberger], Diary of David Zeisberger, a Moravian missionary among the Indians of Ohio, ed. and trans. E. F. Bliss (2v., Cincinnati, Ohio, 1885),1: 3–17; 2: 153–54, 173–75, 179–81, 203–6, 210–11.

Reginald Horsman, “ELLIOTT, MATTHEW,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/elliott_matthew_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/elliott_matthew_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Reginald Horsman |

| Title of Article: | ELLIOTT, MATTHEW |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |