Source: Link

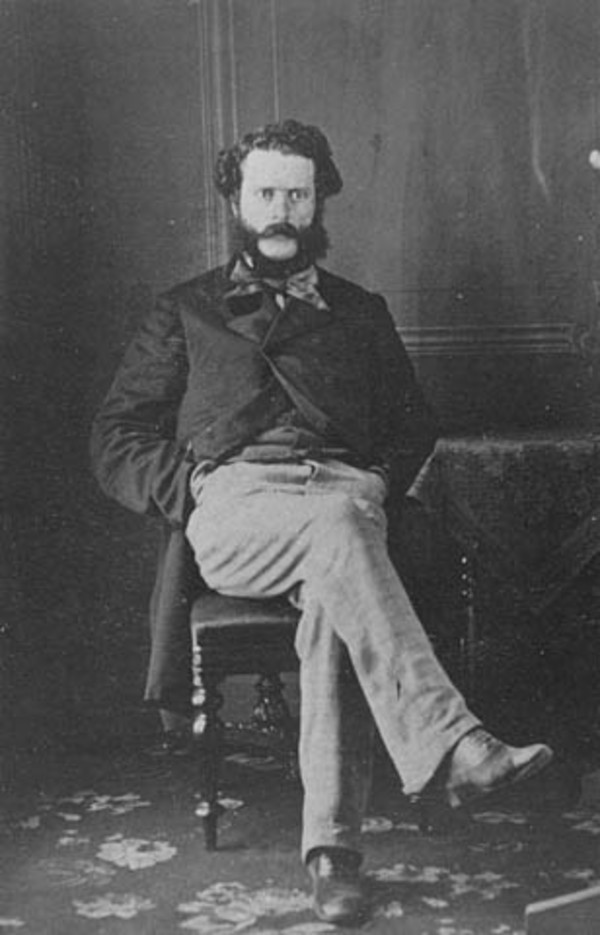

ROBSON, JOHN, businessman, journalist, and politician; b. 14 March 1824 in Perth, Upper Canada, fifth of 16 children of John Robson and Euphemia Richardson, natives of Roxburgh, Scotland; m. 5 April 1854 Susan Longworth in Goderich, Upper Canada; d. 29 June 1892 in London, England.

John Robson’s formal education was received in the common and grammar schools of Perth, where he began his career as a merchant. Later he moved to Montreal and then to Hamilton and Brantford. By 1854 he and his brother Robert had opened a large dry goods store in London. Business there was dull, so the Robsons moved to Bayfield. That April John married in nearby Goderich. When, on 1 April 1859, the brothers dissolved their partnership, John, leaving his wife and two young children in Goderich, went to British Columbia, where his brother Ebenezer was a Methodist clergyman. His wife and children did not join him until February 1864.

Robson had a “very bad attack of the gold fever.” After spending two months panning unsuccessfully, he earned his keep grading, grubbing, chopping wood, making shingles, and cutting timber for the church Ebenezer was building in New Westminster, then the capital of the colony of British Columbia. Until the church got its bell, John, himself a “faithful son of the ‘Old Kirk,’” called people to the Methodist services by blowing a large tin horn, thus “earning for himself the sobriquet, ‘Angel Gabriel.’”

Robson came to the attention of a group of influential citizens who had recently bought the printing-plant of the colony’s only newspaper, Leonard McClure*’s New Westminster Times. The new proprietors, supporters of local reformers, disagreed with McClure on the political future of the colony, and they installed Robson as editor of a new paper, the British Columbian. In his editorial for the first issue, on 13 Feb. 1861, Robson set out his main objectives: “Responsible Government, liberal institutions, the redress of all our grievances, and the moral and intellectual improvement of the people.” The owners were so pleased with his performance that after a year they made him “sole and absolute proprietor as well as editor” of the paper.

The liberal institutions Robson wanted would prepare British Columbia for responsible government. In creating the gold colony in 1858, the British authorities had denied it any semblance of representative institutions. Governor James Douglas* had “absolute powers.” Robson, along with his New Westminster friends, also complained that Douglas, who was governor of Vancouver Island as well, and most of his officials governed the mainland from Victoria. He opposed the tariff policy, which forced “the entire commerce” of British Columbia to pass through Victoria, and called for improved navigation on the lower Fraser River, construction of roads, removal of tonnage duties on goods taken upriver, and designation of New Westminster as a terminus of ocean transportation. He believed that his campaign against the colonial administration cost him the arrangement whereby until December 1862 he printed the Government Gazette on the last page of the British Columbian.

Robson had become somewhat of a local political hero when, earlier that month, judge Matthew Baillie Begbie briefly imprisoned him for having published an anonymous letter hinting that Begbie had been bribed to grant a certificate of improvement on a pre-emption. His next editorial (“A Voice from the Dungeon!”) described the colonial press as “virtually enslaved.” The incident strengthened his view that Begbie was “wholly unfit to administer, alone and unassisted, the Judiciary of the Colony,” but Robson gradually moved from attacking Begbie personally to demanding a general reform of the judicial system. He also participated in local politics in New Westminster. In 1863 he was elected to the municipal council, of which he would be president in 1866–67. But civic government was never his main preoccupation.

Robson’s complaints about the colony’s affairs were initially directed chiefly at Governor Douglas. When Frederick Seymour* replaced Douglas on the mainland in 1864, Robson placed his hopes in the new governor, whose instructions were to create a legislative council, a third of whose members were to be elected. He was generally pleased with Seymour’s “able and liberal” administration but, as the governor prepared to go to England on leave in September 1865, Robson publicly told him, “We have still virtually to submit to the humiliation of ‘Taxation without Representation.’” Yet the following year he reluctantly admitted that perhaps the colony was “not yet ripe” for fully representative institutions. He had been upset when, in the election of November 1865, the Quesnel District allowed Chinese to vote and the people of the district showed their contempt of the government by electing a “petty Government official.” Moreover, he was unsure of the possible effects of the proposed union of the mainland with Vancouver Island, a colony he believed had “rotten institutions,” a “bankrupt exchequer,” a “self-traducing policy,” and “tricky and unscrupulous” politicians. Robson could not quite admit that union was financially sensible because the population and revenues of both colonies were declining while the expense of servicing their debts and maintaining relatively large civil services remained high. By 1865 their combined debt was $1,389,830 and their population, excluding Indians, was approximately 10,700. Robson reluctantly accepted the union of 1866 designed by Seymour because by it Vancouver Island became an integral part of British Columbia.

Despite opposition on the part of government officials, Robson was elected in October 1866 to the Legislative Council of the united colony as member for the city and district of New Westminster. Although during the campaign he had not mentioned representative or responsible government, he was soon discontented with Seymour’s refusal to increase the number of elected councillors, interference from the Colonial Office, and the persistently heavy civil list. He revived his agitation for responsible government, which he defined as “a system by which those officers constituting the government are chosen by the people and are directly responsible to the people from whose pockets the revenue is derived.”

In the Legislative Council Robson had been “the great man on the Westminster side,” but he lost the battle to retain it as the capital. When Victoria was made the capital of British Columbia in May 1868, New Westminster, already suffering from commercial depression, ceased to be “a favourable base” from which Robson could “advocate the broader political questions of the day.” Early in 1869 he moved the British Columbian to Victoria. That city could not, however, support two daily newspapers, and on 25 July the last issue of the British Columbian appeared. A few days later Robson was earning $250 a month as editor of the Daily British Colonist and Victoria Chronicle, which since 1866 had been published by David William Higgins, a strong advocate of responsible government and confederation.

As early as 1862 Robson had predicted that the “scattered and detached” British North American colonies must be linked “into one united Federation which should extend from ocean to ocean.” One of his principal arguments was that confederation would break the Colonial Office’s “yoke of oppression.” He was also keen to have improved overland communication. Yet he warned British Columbians not to enter confederation without terms that provided “every fair and legitimate advantage.” Thus, at a public meeting in New Westminster in April 1868, he moved a resolution favouring “immediate admission into the Dominion of Canada, upon fair and equitable terms.” That fall he was one of the representatives from New Westminster at the Yale Convention [see Amor De Cosmos], which passed resolutions favouring confederation and responsible government, and the same year he was re-elected to the Legislative Council by acclamation. When the new council decided that “under existing circumstances the Confederation of this Colony with the Dominion of Canada would be undesirable, even if practicable,” Robson formally protested that the council “did not fairly reflect public opinion.”

Robson continued to exhort British Columbians to support confederation. Following his move early in 1869 to Victoria, where there was considerable apathy or opposition to it, he emphasized its possible economic advantages for Vancouver Island such as lower tariffs, the restoration of Victoria’s free port status, improved communications, an efficient mail service, increased population, reduced administrative costs, the transfer of Britain’s main Pacific naval base to Esquimalt, a thorough geological survey, and even a low-interest loan to pay for improvements to Victoria’s drainage, sewage, and water systems.

By the time the Legislative Council met in February 1870, the situation had changed dramatically. Governor Seymour, who had opposed confederation, had died, and his replacement, Anthony Musgrave*, Sir John A. Macdonald’s personal choice, had arrived with instructions to promote confederation. Robson observed that union with Canada was now “a foregone conclusion.” Although generally satisfied with the proposed terms of union, he protested against the colonial secretary’s assertion that British Columbia was not ready for responsible government. He described British Columbia’s claim as being much stronger than that of the rebels of Red River. “No union,” he explained, “can be equitable and just which does not give the colony equal political power – equal control over their own local affairs with that possessed by the people of the provinces with which it is to unite.”

Governor Musgrave apparently invited Robson to join the British Columbia delegation sent to Ottawa in May 1870 to negotiate the terms of union, but then, according to Robson, asked him to step down in favour of John Sebastian Helmcken*. Much later Robson said he had declined to go for “business reasons.” He was not happy with the choice of Helmcken, Joseph William Trutch*, and Robert William Weir Carrall* as delegates because they opposed responsible government. David Higgins agreed with Robson, and together they guaranteed the expenses of a lobbyist, Henry E. Seelye, to inform the federal government that any terms that excluded responsible government would not be acceptable to the people of British Columbia. Although the compromise solution, which allowed the province to adopt responsible government if it wished, was less than ideal, Robson accepted the new constitution. British Columbia entered confederation on 20 July 1871.

Robson had not served in the last Legislative Council of British Columbia. Despite the support of Robert Dunsmuir*, an important mine owner, he had lost the election of November 1870 in his new constituency, the Vancouver Island coal-mining community of Nanaimo. In October 1871 he was elected to the first provincial assembly, and he continued to represent Nanaimo until the spring of 1875. His platform, which took responsible government for granted, stressed other important concerns such as the tariff, free schools, homestead grants, retrenchment, and economical administration.

Robson was so certain of a post in the first provincial cabinet that he accepted only a nominal salary of $100 monthly from the Daily British Colonist. He criticized Premier John Foster McCreight*, however, for constructing “an extremely weak” cabinet, whose members did not really believe in responsible government or confederation. Despite this attack, or perhaps because of it, Robson was offered a cabinet seat, but he refused on grounds that the cost of government was already too high. Though he briefly softened his comments on the McCreight administration, Robson was clearly on the opposition side during the first legislative session. He was content that British Columbia did not yet have provincial political parties, believing that the formation of hostile factions was an abuse of responsible government and that “the cry for ‘party government’ is simply a cry for office.” Federally he supported both the Conservatives and the Liberals at different times. In 1889 the Colonist was to observe that because he made “no appeal to party feeling, it would be hard to tell from his remarks that there are two parties in the province.”

Interested in federal matters, Robson had hoped in 1870 for a patronage appointment from Sir John A. Macdonald, but though the prime minister appreciated his work on behalf of confederation, he had no suitable position to offer. Robson nevertheless supported Macdonald’s government, but he prophetically noted that the Colonist’s policy was “strict neutrality, so that we may find ourselves in terms of friendship with the ‘Grits’ should they be the winning party.” When the Pacific Scandal broke in April 1873 [see Lucius Seth Huntington*], Robson called it “the crowning act of Grit malignity,” but as the scandal unfolded his paper began to favour Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberal party. After Mackenzie was asked in November to form a new government, Robson suggested that if the prime minister showed “an honest and earnest disposition” to fulfil the terms of union, British Columbia would forget his earlier unkind remarks about the railway. Robson insisted, however, that the obligation to complete the transcontinental line by 1881 was “cast iron,” and he urged readers to protest any delay in its construction.

Having clearly made a favourable impression on the new government, which had few friends in British Columbia, Robson was appointed in April 1875 paymaster and purveyor for the engineering parties of the Canadian Pacific Railway survey in British Columbia, at an annual salary of $3,000. He was grateful to Mackenzie for the position, which freed him from the “slavery of politics and editorial duties.” Later he was, however, accused by Amor De Cosmos of favouring his friends with contracts. In return for patronage, Robson acted as one of Mackenzie’s unofficial informants on British Columbia. Although some Conservatives considered Robson a “Grit,” he worked easily with Conservatives such as William Smithe* and John Andrew Mara. Nevertheless, with Macdonald’s return to power in 1878, Robson “felt the loss of influence and confidence,” and early the following year the government abolished his position.

For a year and a half Robson was without regular employment, though he did acquire the provincial agency for Confederation Life Association. His personal finances were, however, in good order; by 1876 he had paid off family debts and was contributing to his father’s support. In addition he invested in land and in such enterprises as the B.C. Gold and Silver Mills and Mining Company.

In October 1880 Robson purchased the New Westminster Dominion Pacific Herald. Unlike his approach in his 1861 inaugural editorial for the British Columbian, in which he had laid out a detailed platform, he now merely promised “a thoroughly independent journal” which would place “country before party” and promote “unity of action” in the province. In January 1882 he renamed the paper the British Columbian. Later that year he returned to the legislature as member for New Westminster District and in February 1883 he was appointed provincial secretary (a portfolio which included education), minister of finance and agriculture, and minister of mines. After the death of Premier William Smithe in 1887, the new premier, Alexander Edmund Batson Davie*, retained Robson in the cabinet although Simeon Duck took over finance and agriculture. During the premier’s long illness Robson served as acting premier, and after Davie’s death on 1 Aug. 1889 the lieutenant governor called on Robson to form a government, which he did on 3 August.

Smithe, Davie, and Robson all shared a desire to cooperate with the federal government. In the Herald Robson had repeatedly attacked Premier George Anthony Walkem* for fighting Ottawa, and in May 1883 he told the assembly that the province had “fought Canada for years and years” and had grown “poorer and poorer.” The Smithe government believed in an “honorable peace.” For example, it did not send a representative to the interprovincial conference held at Quebec in October 1887, which called for increased provincial powers and revenue [see Honoré Mercier], even though Robson was in Ottawa at the time on government business. As a cabinet minister and as premier, Robson made several journeys to Ottawa. Though he publicly referred to his discussions there as “successful” and “satisfactory,” by 1892 delays in federal payments for the Esquimalt graving dock and other difficulties led him to muse that he might “adopt the Walkem ‘Fight Ottawa’ policy.”

Robson’s main concerns had always been, and continued to be, within the province. Problems and solutions might vary over time, but he held to certain basic principles throughout his career. He never ceased to advocate political reform, and he was concerned about land settlement and the development of British Columbia. In his 1882 election manifesto he had complained that British Columbia did not have representation by population since 15 electors in the Kootenay sent the same number of representatives to Victoria as 800 voters in the Fraser valley. Renewed mining activity in the Kootenay soon ended that anomaly, but the sudden growth of Vancouver after the completion of the railway made redistribution imperative. In 1890 Robson sought a major redistribution, but other cabinet members, fearful of upsetting the “balance of power” between Vancouver Island and the mainland, opposed it. Robson, explaining that he was “premier not only for his own district but for the whole Province,” reluctantly accepted a minor adjustment until the 1891 census results became available. This decision, which denied his own constituents in New Westminster full representation, suggests he could not control the cabinet.

In advocating female suffrage, Robson was also out of tune with contemporary thinking. Although in 1873 he had claimed “respectable women didn’t want the right” to vote, he later had second thoughts, and by 1885 he was championing the enfranchisement of women because of their good work in voting for school trustees and their support of morality. Almost every year thereafter Robson introduced a private member’s bill to enfranchise women; each time the legislature rejected it.

Robson did share, however, the common British Columbia belief that certain ethnic groups should not participate in the political process. In 1872 he had moved an amendment to the provincial franchise law that disfranchised Chinese and Indians. He had been one of the first to call for a special tax on Chinese because they were “essentially different in their habits and destination,” did not contribute a fair share to the provincial treasury, and competed with “civilized labour.” Although he endorsed the anti-Chinese legislation of the Smithe government, he defended the right of employers to hire Chinese.

His view of Indians, who, until the 1880s, formed the majority of British Columbia’s population, was paternalistic. Despite his belief that the native peoples would become “utterly extinct,” he argued that in the mean time the government had a responsibility to civilize and Christianize them. Thus they should be removed from the immoral towns and cities, protected from whisky traders, and made aware of the force of the law. He recognized Indians’ rights as the “original ‘lords of the soil’” but demanded that treaties be negotiated and reserves established so that Indians should not have more land than they could use well.

In order to develop British Columbia, Robson wanted to make land more readily available to white settlers, and he advocated improved transportation, a liberal trade policy, a sound land policy, and the promotion of immigration. He long attacked the practice of building fine roads to the Cariboo instead of basic roads and trails for the agricultural districts of the Fraser valley, the Kootenay mines, and the interior cattle ranches. As late as 1881 he reminded his coastal readers of the province’s dependence on the prosperity of the interior. Ironically, once Robson joined the cabinet in 1883, critics accused him of spending too much of the public works budget to serve his constituents in the New Westminster District. Robson’s most persistent cause was an “enlightened and liberal land system” to keep out speculators and provide “a free homestead to every bona fide settler.” He complained of inadequate surveys and explorations, of unnecessarily complex laws, and of “soil grabbers” who locked up choice lands. While he was in the cabinet, the government gradually revised the law in order to preserve scarce agricultural lands for genuine settlers. Yet he was willing to use land to assist railways. Between 1883 and 1892 the provincial government set aside almost six million acres for railway subsidies. Robson’s critics charged that he was in the pocket of the CPR, but the fragmentary evidence available indicates he assisted all railways, even ones such as the Nelson and Fort Sheppard Railway which the CPR opposed.

Despite his attacks on speculators, Robson was himself described in 1892 by John Grant, mla for Victoria City, as “the most successful land speculator in the province.” While in the employ of the federal government in the 1870s he had begun acquiring acreage for as little as $30 at English Bay and at Coal Harbour which, he believed, was “the only true and proper terminus for the CPR.” Subsequently he played a prominent role in arranging for the provincial government to give approximately 6,000 acres and private owners to provide one-third of their holdings in return for the CPR’s construction of a 12-mile extension from its terminus at Port Moody to Granville [see David Oppenheimer]. Robson encouraged residents of Granville to apply for municipal incorporation in 1886; when incorporation was debated in the legislature [see Malcolm Alexander MacLean], he championed the name Vancouver though he had once called it “undesirable and confusing.” Robson never denied his involvement in Vancouver real estate but carefully noted he had not acquired land, either directly or indirectly, from the crown. Although he described himself in 1886 as “land poor,” by 1888 some of his lands were being sold at a profit. Unfortunately, the surviving probate records do not reveal the value of Robson’s estate at his death. Thus the claim that he was worth $500,000 cannot be verified, but there is no doubt he died a wealthy man.

Land, even if available, was of little value without settlers. Robson believed it was essential first to determine the agricultural resources of the province. As early as 1864 he had called for exploratory expeditions; as minister of agriculture he dispatched search parties to relatively unknown areas such as the Chilcotin. He also thought it advisable to advertise British Columbia by producing pamphlets and other promotional material, and by appointing agents in San Francisco, England, and possibly Toronto. The province appointed an agent general in London in 1872. Although Robson had doubts about assisted immigration, in 1869 he chaired a select committee of the Legislative Council that recommended subsidizing the immigration of female domestic servants. Even though $5,000 was appropriated for the purpose, only 22 women took advantage of the offer. This experience may have confirmed his uncertainties about such schemes, but by 1890 Alexander Begg* had aroused his enthusiasm for a plan to aid Scottish crofters to develop the deep-sea fisheries of British Columbia. Robson’s death in 1892 deprived the scheme of its most influential supporter and contributed to its failure.

Throughout his career Robson worked for “the moral and intellectual improvement of the people.” He staunchly supported Sabbath observance and favoured temperance measures such as restricting the number of liquor licences and adopting local option (though he did not endorse prohibition). Indeed, he defended brewers against federal legislation that would have confined the provincial brewing industry to New Westminster and Victoria. Robson’s moral beliefs were rooted in his Presbyterian faith. He long served his church as an elder and latterly was a major benefactor of the Presbyterians’ provincial building fund. Yet he was not a sectarian. Recalling the clergy reserves problem in Upper Canada, he had reminded Governor Douglas in 1864 that “in this Colony all denominations of Christians are upon a perfect equality.”

His concepts of religious equality and “intellectual improvement” appeared most clearly in his campaign for public education. Declaring in the Colonist in 1869 that British Columbia did not “possess an educational system,” he called for state-subsidized common schools in every community and a government boarding-school for children from sparsely populated areas. Because education constituted “the best safeguard against crime, indolence, poverty [and] intemperance,” he considered it the duty and interest of “every man, whether he has children of his own to educate or not, to aid in placing within the reach of every child in the community a liberal and wholesome education.”

In the 1860s Robson advocated an educational system similar to that in Ontario (which he believed was the “most perfect” in the world), hoping it would link British Columbia with Canada and encourage immigration. He insisted, however, that it be non-sectarian, so that it might counteract bigotry and cement together “socially, politically and religiously the heterogeneous population of the young colony.” Religious training, he argued, should be provided at home and in Sabbath schools. Yet he did not want “godless” schools. He defended the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer in provincial schools and endorsed the custom of having the major Protestant denominations represented on local school boards and boards of examiners.

Parents in British Columbia had been accustomed to supporting private schools or sending their children away for advanced education. To encourage the local schools, Robson repeatedly called for the establishment of high schools. In 1876 one was opened in Victoria, but when he returned to New Westminster in the early 1880s Robson complained it was unfair to tax the whole province to support a free high school for the benefit of Victoria residents only. The New Westminster high school, which had operated privately for several years, became a free school in 1884, but by the time of Robson’s death only two other cities, Nanaimo and Vancouver, had high schools. Yet in 1886 Robson was already talking about a provincial university and in 1890 his government passed an act to establish one. The plan fell victim, however, to the rivalry between Victoria and Vancouver, and the University of British Columbia would not open until 1915. By 1891–92 there were 10,733 students enrolled in public schools, whereas there had been only 2,693 in 1883, when Robson had become responsible for education. Nevertheless, few British Columbians shared Robson’s enthusiasm for education. Perhaps it was because of this apathy that he was able to centralize the school system to such an extent that critics accused him of running a political machine.

Robson continued to attend public school examinations and closing exercises even when he became premier. Such activities reflected his self-admitted fault of “doing two or three people’s work under the impression that nobody else can do it.” His critics agreed. The Victoria Daily Times suggested on 4 Nov. 1890 that his ministers were too busy with their own commercial and professional interests to provide more than nominal attention to their portfolios. When even friendly journalists suggested Robson could not “dominate his colleagues,” enemies agreed that he was a powerless puppet. His premiership was plagued by poor health, a failure to delegate responsibility, and an inability to command the consistent support of supposed allies in the legislature and the cabinet. Robson opposed the party system, but his administration would have been much easier had there been a party whip.

For several years Robson had wanted rest to preserve his health. In 1890, after winning both his New Westminster District seat and an “insurance” seat in the Cariboo, Robson resigned the former, explaining that he could not do the necessary duties in such a large and important constituency and maintain his other responsibilities and his health. The long illness and death in April 1891 of his younger son, Frederick William, was a blow. In the spring of 1892 his doctor advised a year’s “absolute rest from the work and worry” of the premiership. He tried to free himself of administrative responsibilities, but citizens with real or imagined complaints against the government took their problems directly to him. That May he appointed Colonel James Baker minister of education and immigration, and he actively lobbied for the lieutenant governorship. Perhaps hoping that a change of atmosphere would improve his health, he then set off for London to discuss an imperial loan and crofter immigration. On 20 June he crushed the tip of his little finger in the door of a hansom cab. Blood poisoning set in and nine days later he was dead.

Portraits of Robson suggest he was somewhat gruff. Though active in many organizations, including the Home Guard Volunteer Rifle Company, the St Andrew’s and Caledonian Society, and the Upper Canada Bible Society, he apparently had few personal friends. In later life he seemed sober and serious, but a contemporary remarked that “under a rather cold exterior there was a warm heart and a kindly manner.” As a journalist his pen had sometimes been vitriolic. His attacks on Victoria won him support in New Westminster, and his feuds with rival journalists, notably Amor De Cosmos and James K. Suter, probably helped sell newspapers and certainly contributed to lively political debate. In his promotion of liberal institutions, social and moral improvement, and land settlement, Robson was remarkably consistent during his 31 years of public service. Yet in other areas he sometimes appeared contradictory. He presented himself as a man of the people but moved easily in the company of prominent business leaders and railway executives, and he had little sympathy for the striking miners of Robert Dunsmuir’s Wellington colliery or CPR trainmen. Although he proclaimed the advantages of free institutions, he did not extend them to Indians or Chinese. He believed in making common schools widely available but thought students should pay for secondary education. He favoured freer trade yet wanted to protect home industries. In New Westminster he had been a local booster, but in calling for the extension of such government services as roads and schools to all parts of British Columbia he was never parochial. He persistently attacked land speculation but openly speculated in land himself, and he generously used crown lands to aid railways. Many of the apparent contradictions, however, suggest that he was very much a practical journalist and politician who, except in matters of moral reform, was generally in agreement with his fellow British Columbians and their desire for economic advancement.

Robson was not an original thinker. His most important reform ideas, responsible government and non-sectarian public education, were drawn from his central Canadian experience. So too were his support of confederation and his willingness to cooperate with the federal government. Certainly he was not the only one in British Columbia to favour these policies, but as a journalist and a politician he had an unusually wide forum. He thus became one of the most influential British Columbians of his time and a major contributor to the strengthening of connections with Canada in his adopted province.

PABC, Add. mss 525; H/D/R57; W/A/R57R. Journals of the colonial legislatures of the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, 1851–1871, ed. J. E. Hendrickson (5v., Victoria, 1980). British Columbian, 1862–69, esp. 6 Dec. 1862, 2 Sept. 1865, 18 Aug. 1866, 1882–86, and Daily Columbian, 1886–92. Daily British Colonist and Victoria Chronicle, 1866–72, continued as Daily British Colonist, 1872–86, and as Daily Colonist, 1887–90, 4 Feb. 1892, 11 May 1893. Daily Telegram (Vancouver), 1890. Dominion Pacific Herald (New Westminster, B.C.), 16 Oct. 1880, 29 July 1881. I. E. M. Antak, “John Robson: British Columbian” (ma thesis, Univ. of Victoria, 1972). R. E. Cail, Land, man, and the law: the disposal of crown lands in British Columbia, 1871–1913 (Vancouver, 1974). Olive Fairholm, “John Robson and confederation,” British Columbia & confederation, ed. W. G. Shelton (Victoria, 1967), 97–123. Ormsby, British Columbia. W. K. L[amb], “John Robson and J. K. Suter,” BCHQ, 4 (1940): 203–15. S. G. Pettit, “His Honour’s honour: judge Begbie and the Cottonwood scandal,” BCHQ, 11 (1947): 187–210. Jill Wade, “The ‘gigantic scheme’; crofter immigration and deep-sea fisheries development for British Columbia (1887–1893),” BC Studies, no.53 (spring 1982): 28–44.

Patricia E. Roy, “ROBSON, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robson_john_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robson_john_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Patricia E. Roy |

| Title of Article: | ROBSON, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |