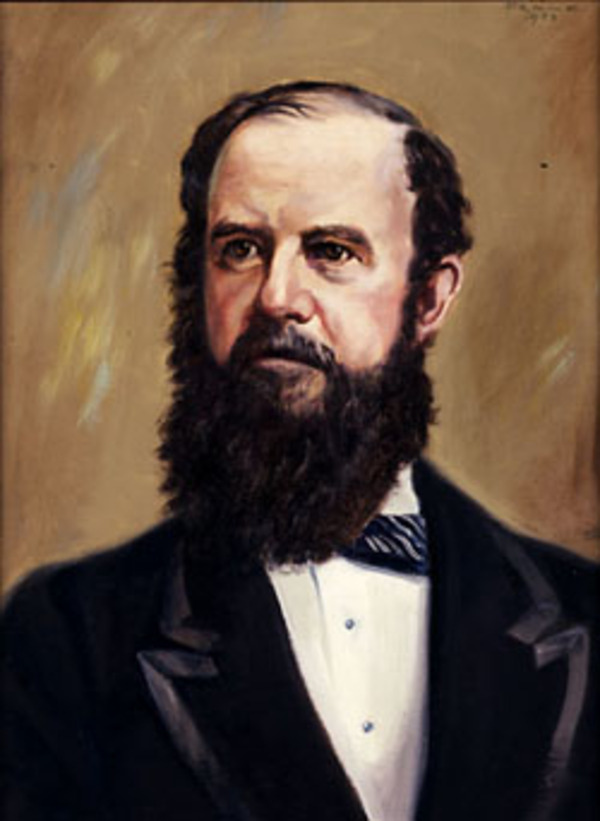

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MUSGRAVE, Sir ANTHONY, colonial administrator and author; b. 31 Aug. 1828 at St John’s, Antigua, third of 11 children of Anthony Musgrave and Mary Harris Sheriff; m. 3 Aug. 1854 Christiana Elizabeth Byam (d. 1859), and they had two children; m. secondly in 1870 Jeanie Lucinda Field; d. 9 Oct. 1888 at Brisbane, Queensland.

Anthony Musgrave’s family had established itself early in the 19th century in Antigua where both his grandfather and father held public office. Anthony received a “strictly orthodox” education at a grammar school in Antigua and what his father regarded as a better education in Great Britain. On his return to Antigua he was appointed, on 14 Sept. 1850, private secretary to Robert James Mackintosh, governor-in-chief of the Leeward Islands. In April 1851 he travelled to England and was admitted as a student to the Inner Temple. On 24 Jan. 1854 the Duke of Newcastle, secretary of state for the colonies, formally notified Musgrave that he had been selected for the position of colonial secretary of Antigua and Musgrave therefore abandoned his legal studies. He served as colonial secretary from 1854 to 1860 and as acting president of Nevis from 1860 to 1861 when he became temporary administrator of St Vincent. The Duke of Newcastle was impressed with Musgrave’s “capacity and zeal” and commissioned him lieutenant governor of St Vincent in 1862.

Musgrave was notified of his appointment as governor of Newfoundland on 12 Sept. 1864 and arrived at St John’s on 5 October. The extensive powers he had wielded in Nevis and St Vincent were in contrast to those he could exercise as governor of Newfoundland, a colony with a much larger population and full responsible government. Throughout his tenure Musgrave was to argue that the solution to Newfoundland’s desperate economic condition, destitute population, and factious politics was the union of the British North American colonies. Confederation was supported by the new secretary of state for the colonies, Edward Cardwell, and from his first speech before a cautious and ambivalent legislature to the end of his governorship in 1869 Musgrave directed his energies to accomplishing that goal. He soon realized that Newfoundland would not be rushed into accepting the scheme and sought to build support for it. In 1865 a new Conservative premier, Frederic Bowker Terrington Carter*, a Protestant, replaced Hugh William Hoyles, and brought with him into the government as colonial secretary Ambrose Shea*, a Roman Catholic. Both Carter and Shea had been delegates to the Quebec conference and were strong supporters of confederation; Musgrave encouraged these changes and could well believe that this coalition forecast the acceptance of confederation after the elections expected in the fall of 1865.

Confederation was not, however, an issue in these elections as the ministry felt it prudent to allow more time to convince voters of the tangible benefits of union as a cure for Newfoundland’s economic problems. In April 1866 Musgrave reported to Cardwell that the new House of Assembly favoured confederation but that all would depend on the terms of admission; he could not, however, persuade the government even to take up the question let alone discuss the possibility of sending delegates to London with those from Canada and the maritime colonies. Musgrave had suggested to Cardwell in February 1866 that he might “turn the screws” by threatening to reduce the naval garrison at St John’s, but the Colonial Office wisely ignored his suggestion, recognizing that initiative for union had to come from the colony itself. Moreover, the French Shore question had caused renewed exasperation between English and French diplomats and Downing Street saw the prospective new negotiator, should Newfoundland join Canada, as an additional encumbrance in an already complicated problem.

Disheartened but still optimistic, Musgrave visited Ottawa in November 1867 to witness the opening of the first session of the new dominion parliament. In long hours of private discussions with Governor General Lord Monck* and Sir John A. Macdonald* he formulated terms of admission to confederation that he thought would be acceptable to his council and assembly. But, when another session of the legislature ended in May 1868, his efforts had still produced no results. The loss of his son in the early summer, together with the ambivalence of officials in the Colonial Office and of the Newfoundland government, left Musgrave disconsolate, and he took leave in England.

During his stay in London, Musgrave was consulted by the new secretary of state for the colonies, the Duke of Buckingham, about confederation and the French fishing treaties. On his return to Newfoundland in December 1868 he was confident that the legislature would agree to confederation and, believing it virtually accomplished, raised the matter of his future employment with Macdonald and the Colonial Office. He knew that Frederick Seymour*’s term as governor of British Columbia was due to expire and asked that he be considered as Seymour’s successor. When Seymour died on 10 June 1869, Musgrave was immediately granted the post. His mandate from the Colonial Office was to unite the Pacific colony with Canada.

Musgrave met his successor in Newfoundland, Stephen John Hill*, at Halifax, and confidently informed him that Newfoundland’s entry into the dominion was inevitable. In the last session of the legislature a greater acceptance of confederation had been evinced and it was to be a major issue in the election in late 1869. Nevertheless the confederates in the event managed to win only nine seats, while the oppositionists captured 21. Many reasons for the collapse of the confederation movement were offered, such as the implacable opposition of most Roman Catholics, divisions among the merchants, and the highly emotional character of the anti-confederate campaign. The Colonial Office preferred to put the responsibility not on local issues, Musgrave, or themselves, but on the Canadians, whom they judged to be precipitate in their haste to have Musgrave sent to British Columbia.

Musgrave arrived in British Columbia on 23 Aug. 1869, having travelled from Halifax to New York, then by rail to San Francisco, and steamer to Victoria. He was the first governor to have travelled to British Columbia by rail and, given his mandate to unite the colony with Canada, his trip west impressed upon him the value of a transcontinental railway in forging the link. The colony was as anxious to receive the governor as the secretary of state had been to send him, for Lord Granville had been reluctant to leave it in the hands of the temporary administrator, Philip James Hankin. There were many long standing grievances, and among government officials little initiative. Far from confident about its future, the colony looked for a bold leader and a decisive administrator.

Musgrave found that the pressing matters of administration confronting him were largely a consequence of Seymour’s neglect of duty. Lord Granville had requested Musgrave’s “serious attention” to Seymour’s disregard for instructions in drawing up the estimates and revenues for 1869; two Supreme Court judges were independently deciding cases in one jurisdiction; crown agents complained that the colony’s financial position was “imperfectly understood” by the colonists; there was no treasurer, the duties being carried out by a clerk “who has given no security for the safe custody of the Public Monies”; the vexed question of the governor’s salary had never been settled; no reply had been made to inquiries from the secretary of state for the colonies respecting revised postal arrangements for the colony. Having been constrained by perfunctory administrative tasks as a governor in Newfoundland, Musgrave was anxious to display his capabilities and determined to direct events. He spent nearly six weeks after his arrival in the colony touring major mainland settlements and in his first six months corrected many of the outstanding problems. He could then devote all his energies to the union of the colony with Canada.

Once Musgrave was installed in British Columbia, Lord Granville’s unqualified support for its inclusion in the dominion was made known. Musgrave himself did not need convincing on the desirability of federations in general, and his future in the colonial service would hinge largely on his success in British Columbia. Yet on his mainland tour he had observed less than unanimous sentiment about confederation; his government also had shown little enthusiasm for the project and in February 1869 the Legislative Council had voted against the measure. However, Musgrave was determined to make the issue a government-sponsored measure and to seize the initiative from individuals, including Amor De Cosmos*, who were campaigning for it and who were in communication with officials in Canada. Musgrave realized also that to overcome the opposition of prominent officials and members of the community such as Henry Pering Pellew Crease*, Joseph William Trutch*, and John Sebastian Helmcken* he would have to ensure adequate provision in the terms of union for government officials. Finally, he felt that if the dominion guaranteed the construction of a railway to British Columbia, the opposition and indifference of the general population to union would soon give way to enthusiasm.

Musgrave convened the Executive Council to discuss terms of entry almost every day from 31 Jan. 1870 through the first two weeks of February, despite being bedridden as a result of a severe leg injury. On 1 January he had appointed Helmcken and Robert William Weir Carrall* as unofficial members of the council, thereby permitting two legislative councillors to take part in the executive’s deliberations. Once terms of union were drafted Musgrave commended them to the Legislative Council, which convened on 15 February; he was careful to emphasize that he had no wish to force confederation on British Columbia without a reference first to its British subjects. He announced his intention to modify the colony’s constitution to institute representative government by providing for the election of a majority of the members of Legislative Council. He also declared himself opposed to any form of responsible government which he believed was too expensive for the colony, a position with which men such as Crease and Helmcken heartily concurred.

Musgrave knew that neither the Colonial Office’s nor his own advocacy of the cause of confederation could ensure unfailing support of government officials in the Legislative Council and he set out to persuade Crease, Trutch, and the influential Dr Helmcken of the importance of their strong support. He took Trutch into his confidence; he knew that Helmcken would agree with the principle of confederation if the terms were attractive to British Columbia; and before the council met he was able to inform Crease of his efforts to secure a judgeship for him. The fact that Crease introduced confederation and presented the first arguments in its favour before the Legislative Council is eloquent testimony to Musgrave’s influence over his officers. Confederation was now a legitimate measure of the government and the issue was successfully removed from the initiative of agitators outside it.

The debate on the proposed terms took place in the Legislative Council from 9 March to 6 April 1870. They were adopted with some modifications and then submitted to the Canadian parliament. In letters to the Colonial Office and to the governor general of Canada, Sir John Young*, Musgrave argued that adoption of the terms in toto as mutually agreed upon would be a certainty if Canada could guarantee construction of a railway. With agitation for confederation beginning to give way to demands for responsible government, Musgrave considered Canada’s promise of a railway as essential if the growing movement for self-government was to be contained.

Musgrave could not travel to Ottawa for negotiations over terms because of his leg injury but he was confident that Trutch, Helmcken, and Carrall, his appointees as delegates, would serve the colony’s best interests. Near the end of July news of the satisfactory conclusion of negotiations reached him and he was particularly gratified by the dominion’s commitment to undertake construction of a transcontinental railway. When the Colonial Office’s approval of his suggestions for altering the colony’s constitution was received on 14 October, he immediately issued writs calling for the election of nine of the 15 members in the new Legislative Council which would be charged with accepting or rejecting the terms of confederation. Until its first meeting Musgrave was given broad powers to oversee the election, including those of determining the qualifications of electors and candidates and of establishing the electoral districts. The only qualification Musgrave imposed upon the male electors was the ability to read English and three months residence in their district.

The election of 1870 was fought more on the question of responsible government and when it should be introduced than on confederation. Therefore, in his speech opening the newly constituted Legislative Council on 5 Jan. 1871, Musgrave promised a bill to provide for its introduction if the council adopted the proposed terms of union. On 20 January the terms were accepted and Musgrave dispatched Trutch to Ottawa and then to London to complete the final arrangements for the colony’s formal entry into the dominion. Relieved by the outcome, Musgrave predicted the result would expedite the entry of Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island.

With responsible government soon to be a certainty, Musgrave was anxious that his guarantees to his officials, whose support for confederation had been essential to the successful outcome, be placed in writing. He introduced a civil list bill to place the appointments of public officials on a legal foundation and to give them higher salaries in order to protect them from the “jobbing combinations” which he considered to be the more deleterious results of responsible government. The bill became law but both it and the governor were criticized by colonists and by officials at the Colonial Office who considered it a mistake for a “moribund legislature,” comprised largely of appointed members, to increase salaries.

After his frustrations in Newfoundland at having to work within the constraints of responsible government and at his failure to get Newfoundland to accept confederation, it was a testimony to his administrative abilities that in less than two years British Columbia was prepared for admission as the sixth province of Canada. He was appointed cmg for his services on 12 April 1871 but he was now anxious to leave the colony. He was offered the first lieutenant governorship of the province but he regarded the cost of living as too high to enable him to stay on at the lower salary he would receive. Moreover, he continued to suffer from the effects of his leg injury and he wanted surgical advice from doctors in London. In addition, his wife Jeanie was pregnant and he wished to avoid crossing the Rockies and the Atlantic in winter. Thus on 25 July 1871 Musgrave left the colony before the return of Joseph Trutch, his successor and the first lieutenant governor of the province.

Musgrave went on to important posts as governor of Natal (1872–73), South Australia (1873–77), Jamaica (1877–83), and Queensland (1885–88) where he died, appropriately, in the midst of a constitutional furore over the principle of the supremacy of a responsible ministry. In South Australia and Queensland, colonies with full responsible government, he had had more time on his hands, and had published his views on a variety of economic questions in journals and pamphlets. Some of these were subsequently revised and published in one volume as Studies in political economy. He was made kcmg in 1875, a further recognition of a distinguished career in colonial service.

Anthony Musgrave was the author of Studies in political economy (London, 1875; repr. New York, 1968).

Duke Univ. Library (Durham, N.C.), Field–Musgrave family papers. National Library of Australia (Canberra), Anthony Musgrave papers. PABC, B.C., Governor (Musgrave), Despatches to London, 11 Jan. 1868–24 July 1871 (letterbook copies); Colonial corr., Anthony Musgrave corr.; Crease coll., Anthony Musgrave, corr. outward; Helmcken papers, Anthony Musgrave, corr. outward; O’Reilly coll., Anthony Musgrave, corr. outward. PAC, MG 26, A. PRO, CO 7/103: Newcastle to Musgrave, 24 Jan. 1854; CO 60; CO 194; CO 398. “The annexation petition of 1869,” ed. W. E. Ireland, BCHQ, 4 (1940): 267–87. B.C., Legislative Council, Journals, 1869–71. [J. S. Helmcken], The reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken, ed. Dorothy Blakey Smith ([Vancouver], 1975). Cariboo Sentinel, 1869–71. Daily British Colonist and Victoria Chronicle, 1869–71. Government Gazette – British Columbia (Victoria), 1869–71. Victoria Daily Standard, 1870–71. ADB. The Colonial Office list . . . (London), 1871. DNB. British Columbia & confederation, ed. W. G. Shelton (Victoria, 1967). R. J. Cain, “The administrative career of Sir Anthony Musgrave” (ma thesis, Duke Univ., 1965). J. W. Cell, British colonial administration in the mid-nineteenth century: the policy-making process (New Haven, Conn., and London, 1970). Creighton, Road to confederation. C. D. W. Goodwin, Economic enquiry in Australia (Durham, 1966). K. M. Haworth, “Governor Anthony Musgrave, confederation, and the challenge of responsible government” (ma thesis, Univ. of Victoria, 1975). W. P. Morrell, British colonial policy in the mid-Victorian age: South Africa, New Zealand, the West Indies (Oxford, 1969). W. L. Morton, The critical years: the union of British North America, 1857–1873 (Toronto, 1964). E. C. Moulton, “The political history of Newfoundland, 1861–1869” (ma thesis, Memorial Univ. of Newfoundland, St John’s, 1960). V. L. Oliver, The history of the island of Antigua, one of the Leeward Caribbees in the West Indies, from the first settlement in 1635 to the present time (3v., London, 1894–99). Ormsby, British Columbia; “The relations between British Columbia and the dominion of Canada, 1871–1885” (phd thesis, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pa., [1937]). J. H. Parry and P. M. Sherlock, A short history of the West Indies (London and New York, 1956). Barry Scott, “The governorship of Sir Anthony Musgrave, 1883–1888” (ba honours thesis, Univ. of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia, 1955). Waite, Life and times of confederation. W. M. Whitelaw, The Maritimes and Canada before confederation (Toronto, 1934; repr. 1966). Isabel Bescoby, “A colonial adminstration; an analysis of administration in British Columbia, 1869–1871,” Canadian Public Administration (Toronto), 10 (1967): 48–104. K. M. Haworth and C. R. Maier, “‘Not a matter of regret’: Granville’s response to Seymour’s death,” BC Studies, 27 (autumn 1975): 62–66. F. W. Howay, “Governor Musgrave and confederation,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 15 (1921), sect.ii: 15–31. K. A. Waites, “Responsible government and confederation: the popular movement for popular government,” BCHQ, 6 (1942): 97–123. W. M. Whitelaw, “Responsible government and the irresponsible governor,” CHR, 13 (1932): 364–86.

Kent M. Haworth, “MUSGRAVE, Sir ANTHONY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/musgrave_anthony_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/musgrave_anthony_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kent M. Haworth |

| Title of Article: | MUSGRAVE, Sir ANTHONY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |