Source: Link

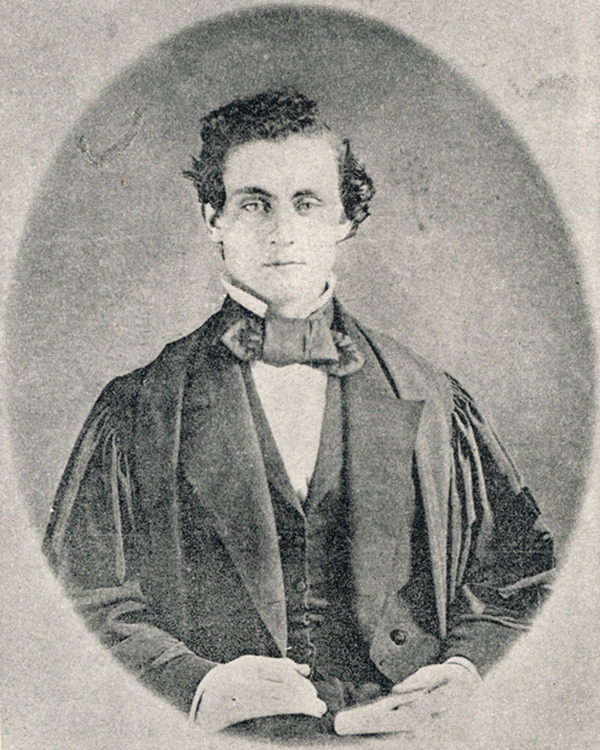

McMICKING, THOMAS, gold-seeker, municipal official, and author; b. 16 April 1829 in Stamford Township (city of Niagara Falls), Upper Canada, eldest son of William McMicking and Mary McClellan; m. 12 July 1853 Laura Chubbock, and they had two girls and two boys; d. 25 Aug. 1866 near New Westminster, B.C.

Thomas McMicking’s grandfather had come from Scotland and had settled at Stamford about 1780. Thomas attended the local public school and Knox College, Toronto. He was a teacher at Stamford and Queenston, and then in business at Queenston. In June 1861 he stood for election as the Clear Grit candidate at Niagara but was defeated by the Conservative John Simpson*.

In autumn 1861, when news of the rich gold finds in the Cariboo reached Canada West, Thomas was the leading spirit in organizing a party of 24 or 28 to travel overland to the Cariboo from the Queenston and St Catharines area. The party, including Thomas’ youngest brother, Robert Burns McMicking, left Queenston in April 1862. It travelled through the United States by rail and steamer to St Paul on the Mississippi, by coach to the Red River, and then by steamer to Fort Garry.

Other parties (perhaps as many as 20 from Canada West, two from Canada East, and one from New York State), were organized independently and travelled in much the same manner on their own to Fort Garry. At St Paul and Georgetown in Minnesota, or at Fort Garry, these parties bought animals, supplies, and Red River carts for the trek west. Thomas McMicking met the new governor of Rupert’s Land, Alexander Grant Dallas*, at Georgetown on 12 May 1862. Dallas and his wife joined the Overlanders for the journey on the steamship International to Fort Garry.

On 5 July, at Long Lake just west of Fort Garry, 138 men from at least 15 of the original groups organized themselves into a single party; Thomas McMicking was elected captain with an advisory committee of 13, approximately one member for each original party. McMicking’s group adopted rules governing its order of march, behaviour in camp and en route, and defence against possible Indian attack. McMicking wrote later in the year that “We found the red men of the prairies to be our best friends.”

As McMicking’s party proceeded westward, additional members, notably the family of Augustus Schubert who travelled with horse and buggy across the prairies, joined the group. Catherine Schubert was the only woman among the Overlanders, who had a policy of excluding women, thinking their presence inappropriate in large groups of men. Yet even this one family proved an asset for the morale and work of the expedition.

Two smaller parties followed the main contingent. One had left Toronto with 45 men (the largest number of any group) under the authoritarian leadership of former policeman Stephen Redgrave, but it was now split by dissension; some members transferred to other groups, including McMicking’s. Redgrave himself was one of nine of the original Torontonians to join a group led by the adventurer Timolean Love in a futile attempt to find gold on the upper North Saskatchewan. After wintering there, and encountering Eugene Francis O’Beirne who delivered sermons and sponged upon them, most of Love’s party crossed into the Cariboo in 1862. The other party was that of Dr Symington, and it followed the two others. Its movements and membership are little known; when Archibald McNaughton of McMicking’s party fell back with an injured comrade he travelled with this group for a time.

The main party under McMicking reached Fort Edmonton, the last depot for supplies, on 21 July 1862. When it left eight days later, some of its members stayed behind to prospect before crossing the mountains the next year. McMicking crossed with pack animals, proceeding up the Athabasca and then the Miette River, and over the height of land by Yellowhead Pass to reach the upper Fraser and Tête Jaune Cache. Here, near starvation, McMicking’s party was provisioned by a band of Shuswaps. Owing to disputes about the best route to follow, a meeting of those still with the party was held on 1 September dissolving the agreement of 5 July.

About 20 of the members, including Catherine and Augustus Schubert and their three children, chose to cross to the North Thompson. On it two drowned, and the remainder reached Thompson’s River Post (Kamloops) destitute and near their end on 13 October; the next day Mrs Schubert, with the help of an Indian woman, gave birth to a fourth child, Rose, the first white girl born in the interior of British Columbia. The main party, including McMicking, had chosen instead to descend the Fraser River. Some went on rafts, at no loss of life, but of a group that used dugout canoes three drowned and one died of pneumonia after surviving an upset. Thomas McMicking, travelling by raft, reached Quesnelle Mouth (Quesnel) on 11 September. Here he drew up a summary of expenditures by the Queenston parties until that time. They worked out to $97.95 per person. He commented drily on their purchases: “Our mining tools were the only articles . . . that we found to be unnecessary.” He tried, although the season was late, to reach the diggings at Williams Creek, but turned back because of the weather and discouraging reports of miners departing for the coast.

Many of the Overlanders left the country without ever mining. As a gold seeking expedition the trek of the Overlanders of ‘62 was almost fruitless. A few returned to the Cariboo in 1863 but they found the gold deposits becoming exhausted. Late in 1862 Thomas McMicking went down from the Cariboo to New Westminster, where he was befriended, as many Overlanders were, by John Robson*, editor of the British Columbian. McMicking worked for a short time in a shingle mill. He also quickly prepared an interesting, well-written narrative of the journey which was published in the British Columbian between 29 Nov. 1862 and 23 Jan. 1863 in 14 instalments. This is the basic published primary document on the Overlanders.

Thomas McMicking’s education and talents soon won him civic responsibility. In 1864 he was appointed town clerk for New Westminster and in April 1866 deputy sheriff. He was active in the affairs of St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church and was a member of the volunteer Hyack Fire Company. On 26 June 1866 he was secretary of a meeting called to organize a local home guard, when news arrived from Canada of the Fenian raids. The corps subsequently elected him 1st lieutenant. A short time afterwards, however, on 25 August during a family visit to a friend ten miles below New Westminster, McMicking’s second son William Francis, six years old, fell into the Fraser River. The father went to the rescue, but with his son was swept under a boom and drowned.

McMicking was one of the few who came to the British Columbia gold-rush overland from Canada as against the tens of thousands who came by sea. Apart from a handful in 1859, nearly all the Canadians who did arrive by land were in the three 1862 groups; their exact number is hard to determine, but Thomas McMicking’s figure of 200 seems the most reliable. Their purpose in making the journey was not fulfilled but it had other positive results. The passage of the Overlanders through the Rocky Mountains helped to show that the geographical barriers to union between Canada and British Columbia could be overcome.

Many of the Overlanders who remained in British Columbia became outstanding contributors to the development of the province, a result undoubtedly of the self-sufficiency and of the organizational capacity developed by the journey. One of these was Robert Burns McMicking, a resident of the province till his death in 1915 and a central figure in the introduction of the telegraph, the telephone, and electric power into British Columbia.

Thomas McMicking was author of an “Account of a journey overland from Canada to British Columbia during the summer of 1862 . . . ,”British Columbian (New Westminster), 29 Nov., 3, 10, 13, 17, 20, 24, 27, 31 Dec. 1862; 10, 14, 17, 24, 28 Jan. 1863 (typescript at PABC).

PABC, R. H. Alexander, Diary, 29 April–31 Dec. 1862; R. B. McMicking, Diary, 23 April 1862–29 April 1863; Miscellaneous material relating to Thomas McMicking, R. B. McMicking, memo, 3 Dec. 1912; Stephen Redgrave, Journals and sundry papers, 1852–75 (typescript); J. A. Schubert, Notes of conversation, 18 July 1930 (typescript). University of British Columbia Library, Special Coll. Division (Vancouver); A. L. Fortune, coll. of addresses and narratives (type script); John Hunniford, Journal and observations (typescript). R. B. McMicking, “Second overland journey,” Year book of British Columbia . . . , comp. R. E. Gosnell (Victoria, 1897), 100–2. J. B. Kerr, Biographical dictionary of well-known British Columbians, with a historical sketch (Vancouver, 1890), 253–61. Margaret McNaughton, Overland, to Cariboo; an eventful journey of Canadian pioneers to the gold fields of British Columbia in 1862 (Toronto, 1896; repr., intro. V. G. Hopwood, Vancouver, 1973). M. S. Wade, The Overlanders of ‘62, ed. John Hosie (Victoria, 1931).

Victor G. Hopwood, “McMICKING, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcmicking_thomas_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcmicking_thomas_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Victor G. Hopwood |

| Title of Article: | McMICKING, THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |