Source: Link

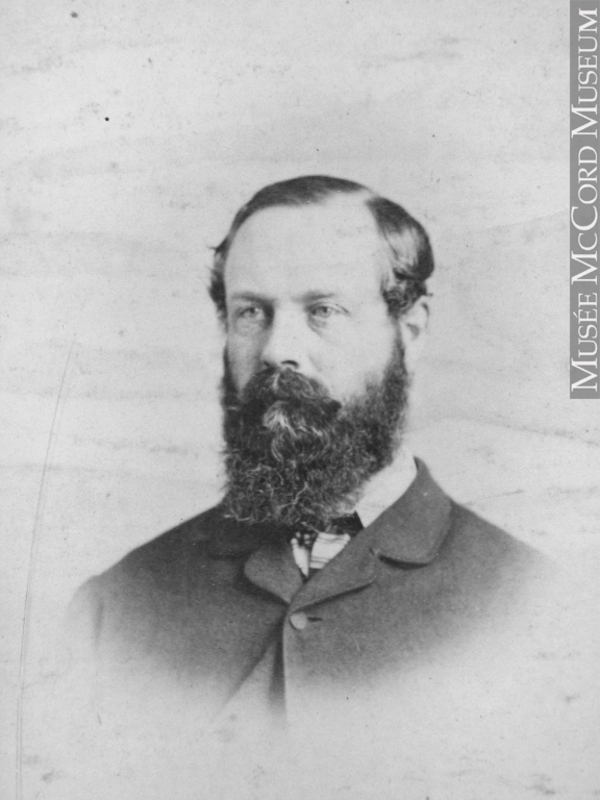

MONCK, CHARLES STANLEY, 4th Viscount MONCK, governor general; b. 10 Oct. 1819 in Templemore (Republic of Ireland), eldest son of Charles Joseph Kelly Monck, 3rd Viscount Monck, and Bridget Willington; m. 22 July 1844 his cousin Lady Elizabeth Louise Mary Monck, a daughter of Henry Stanley Monck, 1st Earl of Rathdowne, and they had at least two sons and two daughters; d. 29 Nov. 1894 at Charleville, his seat in County Wicklow (Republic of Ireland).

When Charles Stanley Monck was appointed governor general of British North America on 2 Nov. 1861, as successor to Sir Edmund Walker Head*, articles in the French Canadian press linked his family with that of the celebrated Charles Le Moyne* de Longueuil. The former descended from the Norman nobleman Guillaume Le Moyne, who had settled in Devon after the conquest of England in 1066. The Monck viscountcy dated from 1801, and Charles Stanley succeeded to its titles and estates when his father died on 20 April 1849.

Monck was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and then at the Inns of Court until he was called to the bar in June 1841. By then he had become active in Irish politics as a liberal and begun a career which, after his defeat as a candidate in Wicklow in 1848, led him to the House of Commons as the member for Portsmouth in July 1852. He received an appointment as lord of the Treasury in Lord Palmerston’s administration in March 1855 and held it until the government fell in 1858. Defeated at the general elections that followed, he decided to leave active politics.

With his estates, Monck had also inherited very large debts. He was thus chronically in need of a secure income, and when offered the governor generalship by Lord Palmerston in 1861, he accepted it – as he later admitted simply and frankly – “for the money.” A relative unknown, who had played an unimpressive role in politics and lost even his minor office after a mere three years, he found himself at the head of British North American affairs during one of the most difficult and turbulent periods in their history. Perhaps even to his own surprise, he succeeded in making himself indispensable in guiding the colonies peacefully through the bitterness, fear, and disquiet that characterized their relations with the republic to the south, and in keeping solid control of the otherwise wild, chaotic, and intense politics that marked each one of their governments.

Monck arrived at Quebec in the fall of 1861 and took office on 28 November, just as war with the United States seemed inevitable over the Trent affair [see Sir Charles Hastings Doyle*]. Throughout his term, he found relations inflamed by renewed crises such as the events surrounding the St Albans raid in 1864 [see Charles-Joseph Coursol*] and the menace of Fenian invasions in 1866 [see John O’Neill*]. His friendship with Lord Lyons, the British minister at Washington, and his personal sympathy for the North helped him significantly in cooling tempers on the American side and mitigating the outrage of Union politicians at Confederate use of Canadian territory. His own good connections with the successive military commanders of British North America, Sir William Fenwick Williams* and Sir John Michel*, also strengthened him in pressing the imperial government for a single military system for all the colonies, one capable of operation even in the absence of political union. He was in turn greatly influenced by the counsel of his secretary and confidant, Dennis Godley, a British colonial reformer and hard-working official, whom Canadians nicknamed “the Almighty,” and whose views on British North American union and independence encouraged many of his political initiatives.

Confederation soon became Monck’s aim. In June 1864, when advised to dissolve the legislature of the Province of Canada by Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché*, whose supporters had just been defeated in the House of Assembly, he urged the forming of what became the “Great Coalition,” and he intervened personally to persuade George Brown* to join the ministry. From then onwards, he played a leading role in preparing for federal union, composing dispatches, attending conferences in Charlottetown in September 1864 and at Quebec the following month, and keeping in close, constant, and personal touch with lieutenant governors Sir William Fenwick Williams of Nova Scotia and Arthur Hamilton Gordon* of New Brunswick. He was in London for the conference at the Westminster Palace Hotel in the fall of 1866, and, in February 1867, took part in the debate on the British North America Act in the House of Lords, to which he had recently been elevated as a peer of the United Kingdom, perhaps precisely to allow him this intervention.

Although Monck had never wanted to be an absentee landlord, and by 1866 was anxious to return to manage his estates, he agreed to stay in Ottawa as the first governor general of the new dominion. Like others he had wished it to be designated as a kingdom, and for his office to be that of a viceroy, who would also be the chancellor of a new Canadian order of knighthood. He dutifully remained to commission John A. Macdonald, who had been the elected chairman of the London conference, as prime minister and to recommend the names of the first federal cabinet. Then, in a typically low-key manner, he played down the ceremonies on 1 July 1867, taking his own new oath of office, swearing in the prime minister and the lieutenant governors, as well as reviewing the troops, in a most informal way and in plain clothes.

Monck left Canada from Quebec on 14 Nov. 1868, after seeing to the final purchase of Rideau Hall and its 80 acres of grounds as an official residence for succeeding governors general. He had chosen the site during a visit to the new capital in 1864, moved in with his family in August 1866, and supervised the construction, renovations, and furnishings which soon transformed the original villa built by the architect Thomas McKay* in 1838 into a dignified and homelike residence.

To honour his achievements in Canada, Monck was made a gcmg in June 1869 and called to the Privy Council on 7 August. After his return to Ireland, he was appointed in 1871 a member of the Church Temporalities and National Education commissions, and continued to administer the first until 1881. Between 1882 and 1884 he was a commissioner of the new Irish Lands Act, and between 1874 and 1892 he held the office of lord lieutenant and custos rotulorum of County Dublin. He continued, however, to be in financial difficulties and, towards the end of his life, went into business in London. But he was crippled with arthritis, and after the death of his wife in 1892 he retired to his estates.

Lord Monck came out to Canada an obscure man, inexperienced, discreet, and unfamiliar. An outsider to establishment and empire, he lacked style and imagination. Throughout his seven-year tenure, he seems never to have sought popularity, nor ever to have found it. Politicians disliked him. People found him dull. Still, those who knew him well and worked with him closely came to respect him and admire his great qualities of patience, helpfulness, and genuine impartiality. “I like him amazingly,” Sir John A. Macdonald wrote to Charles Tupper* on 25 May 1868, “and shall be very sorry when he leaves, as he has been a very prudent and efficient administrator of public affairs.” A private man, devoted to his household and friends, he was, in small groups, witty, warm, supportive, kind, courteous, and always available. He and Lady Monck, a cheerful and happy person, created a loving and unpretentious home atmosphere, especially in Quebec, where after the fire of 1863 they rebuilt to their specifications the official residence at Spencer Wood. And so at Rideau Hall, as at Charleville.

Still, whatever his public shortcomings or considerable private qualities, Lord Monck, in British North America during a most difficult time, displayed as few others have done that enviable degree of shrewdness and practical common sense by which a nineteenth-century governor general could use to best advantage the power and influence of his office to bind at once colonial politicians to imperial policy and the peoples of the colonies to each other.

F. E. O. Monck, My Canadian leaves: an account of a visit to Canada in 1864–1865 (London, 1891). Burke’s peerage (1890). DNB. Elisabeth Batt, Monck, governor general, 1861–1868 (Toronto, 1976). D. [G.] Creighton, Macdonald, old chieftain; The road to confederation; the emergence of Canada: 1863–1867 (Toronto, 1964). R. H. Hubbard, Rideau Hall: an illustrated history of Government House, Ottawa; Victorian and Edwardian times (Ottawa, 1967). W. L. Morton, The critical years: the union of British North America, 1857–1873 (Toronto, 1964). C. P. Stacey, “Lord Monck and the Canadian nation,” Dalhousie Rev., 14 (1934–35): 179–91. R. G. Trotter, “Lord Monck and the Great Coalition of 1864,” CHR, 3 (1922): 181–86.

Jacques Monet, “MONCK, CHARLES STANLEY, 4th Viscount MONCK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/monck_charles_stanley_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/monck_charles_stanley_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques Monet |

| Title of Article: | MONCK, CHARLES STANLEY, 4th Viscount MONCK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |