Source: Link

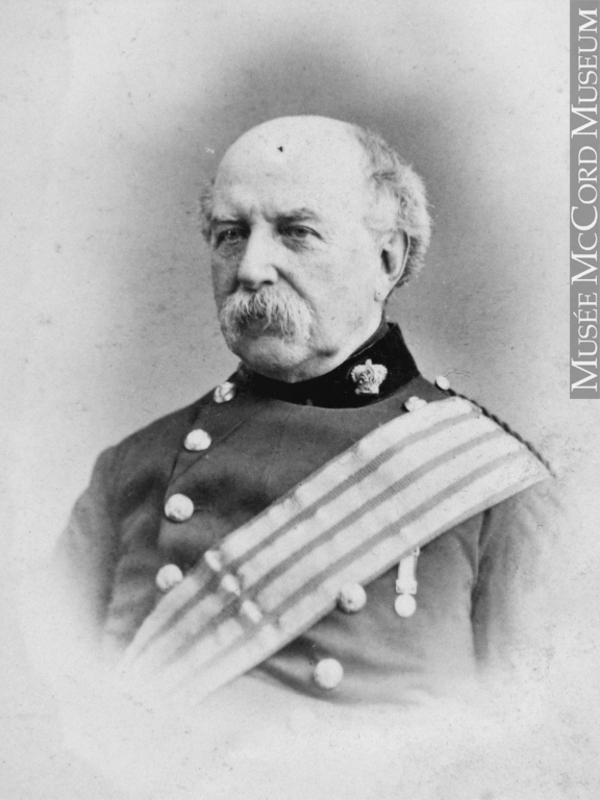

WILLIAMS, Sir WILLIAM FENWICK, soldier and military and colonial administrator; b. 4 Dec. 1800 in Annapolis Royal, N. S., son of Maria Walker and possibly Thomas Williams; d. unmarried on 26 July 1883 in London, England.

It was widely believed at the time of his birth and throughout his career that William Fenwick Williams’ father was Edward Augustus*, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, who had been living in Halifax and who left for England, with Thérèse-Bernardine de Saint-Laurent*, in August 1800. Williams himself made no effort to discredit this possibility, which would have meant he was Queen Victoria’s half-brother. Williams’ putative father, however, was the commissary general and barrack master of the British garrison at Halifax. William, like his elder brother Thomas, was destined for a military career and in May 1815 he entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich (London) England. Following his graduation he spent some years travelling and, owing to the slowness of all military appointments in the decade after Waterloo, was commissioned 2nd lieutenant in the Royal Artillery only in July 1825. He served on army stations in Gibraltar, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and England, and was promoted 2nd captain in 1840, 1st captain in 1846, and brevet colonel in 1854. In 1841 he went to Constantinople (Istanbul) with Captain Collingwood Dickson to reform the Turkish arsenal. In 1843 he was appointed British commissioner in charge of defining the Turkish-Persian border, a task that took nine years and for which he was awarded a cb in 1852.

When the Crimean War broke out in 1854, Williams was appointed British commissioner to the Turkish army in Anatolia, to help reorganize it after the Turks had been badly defeated by the Russians in the opening months of the war. He reached Kars, in the far northeast of Turkey, in September 1854 but returned shortly to Erzurum to persuade Turkish authorities to reinforce Kars. Receiving news in May 1855 of a Russian plan to take Kars, he went back there on 7 June. A Russian army of 25,000 attacked a week later. It was repulsed with heavy losses, but Kars was invested and another Russian attack was launched on 7 August. The Russian general, Murav’ev, attacked again on 29 September, and failed, losing 6,000 men. By now, however, hunger, cold, and cholera were beginning to take effect on the population of Kars, and early in November, when news came that there would be no reinforcements, Williams decided to negotiate a surrender. He told Murav’ev that if unconditional surrender were insisted upon, they would spike every gun, burn every flag, and then let him work his will on the town’s survivors. Murav’ev was generous to such a spirited enemy; the garrison marched out with their flags and with their swords. Williams was given a comfortable imprisonment at Ryazan, and when the Crimean War ended a few months later he was presented to Czar Alexander II before returning to London in March 1856.

There he was lionized. His defence of Kars had been one of the great achievements of the British army in a war in which achievements had been few. Williams was made a kcb and given an Oxford dcl; France gave him the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour; and the British parliament voted him an annual pension of £1,000 for life. He was made a major-general, given command of the Woolwich garrison, and elected to parliament for Calne in July 1856, a seat he held until April 1859.

He then accepted appointment as commander-in-chief of the British forces in British North America, and was thus in a position to organize the defences of the Province of Canada when the American Civil War broke out in April 1861. Williams believed Southern independence was permanent, and that in consequence the North would seek in British North America, especially Canada West, “a balance for lost theatres of ambition.” As he wrote to the Duke of Cambridge, “our danger begins when their war ends . . . .” Three additional British regiments were sent to Canada at Williams’ request and, in December 1861, at the time of the Trent crisis, a further 15,000 troops followed. Williams ordered heavy batteries set up at Toronto and Kingston. In fact, Governor General Lord Monck* had trouble holding Williams in and convincing the old warhorse that Britain was not yet actually at war with the United States. Williams’ energy was not matched, however, by Canada’s provincial legislature; in May 1862, when the crisis was to all appearances over, it threw out the militia bill by which the government of George-Étienne Cartier* and John A. Macdonald* proposed to raise an active militia force of 50,000 men at an annual cost of $1,110,000. The succeeding moderate Reform government strenuously opposed any significant Canadian defence measures. Hence Colonial Secretary Edward Cardwell insisted in 1864 on the concentration of British forces in the valley of the St Lawrence, rather than having them strung out in small units from Quebec to London, Canada West, without any substantial support from a militia in the event of American military action. Cardwell’s insistence drew no immediate objection from Williams, who believed that neither the government nor the people of Canada had lived up to the promises of military support made during the Trent crisis and felt that the withdrawal of troops from much of western Upper Canada might force them to make adequate defensive preparations. Williams complained to London on 13 June 1864 of Canada’s “fruitless party politics,” but he wrote when they were at a particularly unproductive stage, on the day before the fall of the Étienne-Paschal Taché*–Macdonald ministry. A week later, however, the Taché–Macdonald–George Brown* coalition was formed; it was committed to the federation of all the British North American provinces and, imperial authorities-hoped, the creation of a Canadian defence force.

Williams’ next tour of duty was to be in his native province. The lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, Sir Richard Graves MacDonnell, had been frequently critical of moves toward confederation, which the British government, by the end of 1864, firmly supported. The difficulties of persuading Nova Scotia to adopt confederation were substantial, but Cardwell decided the chances would be much improved by a positive and likeable lieutenant governor. Sir Richard went to Hong Kong, and Sir William Fenwick Williams arrived in Nova Scotia in November 1865.

Williams was a soldier, told to do what he could. His good temper and military fame had made him popular in his native province even before he arrived, but Nova Scotians who opposed confederation could be under no illusions. When chided by Lord Monck for having encouraged the anti-confederate government of Albert James Smith in New Brunswick by not mentioning confederation in his speech from the throne in February 1866 – an omission both deliberate and regarded by Nova Scotia Premier Charles Tupper* as essential – Williams admitted to Arthur Hamilton Gordon*, lieutenant governor of New Brunswick, that the omission had deceived few people. “My total abandonment of Confederation [in the throne speech] is too much like Punch even for their sincere belief. They know what I was sent here for.” With confederation in mind, in March Williams invited William Annand, leader of the anti-confederates in the Nova Scotia assembly, to suggest a new confederation conference. Annand refused but another opposition member, William Miller*, agreed. This move was received most favourably by Tupper, as well it might be; but it did not break the log jam, for that depended on a clear-cut commitment by the Smith government in New Brunswick either for or against confederation. Once the Smith government was forced out of power there, as it was on 10 April, then Tupper could, and did that same day, move the resolution for confederation in the Nova Scotia assembly. A week later, on 17 April, while British troops were being sent from Halifax by ship to meet the Fenian threat in the St Croix estuary, the Nova Scotia assembly passed the confederation resolution by a vote of 31 to 19. When Cardwell retired as colonial secretary in July 1866, he warmly congratulated Williams. “Let us rejoice together,” he wrote, “in the success which has attended your Mission, & in the now, I trust, secure & certain union of the B.N.A. Provinces.”

Sir William Fenwick Williams continued as lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia until October 1867, when he was replaced by Charles Hastings Doyle. Williams was a free man for the next three years and spent some time in Sussex, N.B., where he had relatives, and also travelled to England. In September 1870 he was made governor and commander-in-chief of Gibraltar, and stayed there until 1876. His last official appointment was as constable of the Tower of London, in May 1881. Williams died at his hotel in Pall Mall and was buried in Brompton cemetery.

Williams was an interesting example of a colonial-born son of a British military family. He had been a good soldier, with something of a colonial’s self-reliance and willingness to take on responsibility. He was firm as a rock when it came to duty, but he was never a slave-driver. However, one must not assume that, in the conventional phrase of the time, he lived and died “a gallant old soldier.” Edward William Watkin described him in 1861 as “a worn out old roué who might get the 10,000 men the Iron Duke spoke of into Hyde Park, but who never could get them out again.” By 1861 this was an all too general opinion. The young, eager British colonels who came out to Canada in December 1861, Garnet Joseph Wolseley* for example, believed that if war with the United States really came, Williams would have to be replaced. When in 1870 it was suggested to the British government that Williams might be given charge of the Red River expedition, Edward Cardwell, then secretary for war, agreed with Colonial Secretary Lord Granville that Williams would be hopeless. Useful enough for military command in time of peace, and in carrying confederation in Nova Scotia, Williams was now, in Cardwell’s mind, impossible for “a post of great difficulty or requiring great power of discretion.” The comment about difficulty is understandable – Williams was now nearing 70 – but the reference to discretion is biting. Williams may indeed have had, as a friend said, “the kindliest, gentlest heart that ever beat”; that was not inconsistent with his having become, at the end of his career, as many others doubtless do, something of a Colonel Blimp.

[There are obituaries of Sir William Fenwick Williams in the Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, the Morning Chronicle (Halifax), and the Times (London), all for 28 July 1883, and in the Illustrated London News, 4 Aug. 1883. There is a small but useful collection of Williams papers in the N.B. Museum consisting mainly of letters he received. During the period of his North American command from 1859 to 1865 Williams wrote some 300 letters to the Duke of Cambridge, commander-in-chief of the British Army. These are in the Royal Arch., Windsor, Eng. There are letters from Williams in the Cardwell papers and in the Carnarvon papers at the PRO (PRO 30/48 and PRO 30/6 respectively), and in the Stanmore (Arthur Hamilton Cordon) papers at the UNBL (MG H 12a). More official sources are his dispatches to the secretary of state for war, PRO, WO 1; his dispatches from Nova Scotia, PRO, CO 217; and his very interesting telegram book, PANS, RG 2, sect.2, 5–6.

For an eye-witness account of the siege of Kars see Humphry Sandwith, A narrative of the siege of Kars . . . (3rd ed., London, 1856). The most useful secondary source for his British North American career is Adrian Preston, “General Sir William Fenwick Williams, the American Civil War and the defence of Canada, 1859–65: observations on his military correspondence to the Duke of Cambridge, commander-in-chief at the Horse Guards,” Dalhousie Rev., 56 (1976–77): 605–29. See also Elisabeth Batt, Monck, governor general, 1861–1868 (Toronto, 1976); Creighton, Road to confederation; K. G. Pryke, Nova Scotia and confederation, 1864–74 (Toronto, 1979); C. P. Stacey, Canada and the British army, 1846–1871: a study in the practice of responsible government (rev. ed., [Toronto], 1963); and Waite, Life and times of confederation; as well as Dent, Canadian portrait gallery, IV: 5–9, and Notman and Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, I: 51–66. There is a good article on Williams in the DNB, but it omits his North American career. p.b.w.]

P. B. Waite, “WILLIAMS, Sir WILLIAM FENWICK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/williams_william_fenwick_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/williams_william_fenwick_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | P. B. Waite |

| Title of Article: | WILLIAMS, Sir WILLIAM FENWICK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |