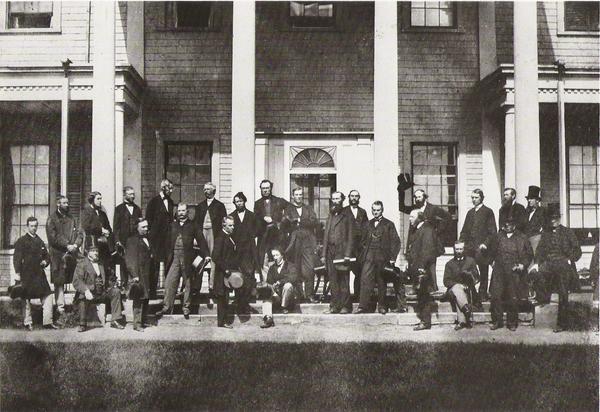

The Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences of 1864

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The conferences held at Charlottetown in Prince Edward Island and Quebec City in 1864 were fundamental to the making of modern Canada. The topic of both meetings was British North American federal union, an idea that reached back to the early 19th century and found increasing support during the 1850s. But it proved impossible to translate the theory into practical politics, and the prospect generated little enthusiasm in Great Britain – as the failure of Alexander Tilloch Galt’s 1858 plan for federal union illustrated.

In the early 1860s, however, the political ground was shifting. The American Civil War (1861–65) highlighted the need for a coordinated British North American defence policy. In 1861 Britain and the United States had come perilously close to war; thousands of British troops had been rushed across the Atlantic and then were compelled to slog their way through the snows of New Brunswick to reach the railway connection to the United Province of Canada (present-day Ontario and Quebec). From the British perspective, a consolidated British North America could provide a stronger counterbalance to American power, and an intercolonial railway linking the Maritimes to Canada could serve important strategic as well as commercial interests. Confederation could also improve east–west economic links if the Americans abrogated the Reciprocity Treaty concluded by the governor, Lord Elgin [Bruce], in 1854 – which indeed they did in 1866.

By 1864 stresses and strains within Canada were near the breaking point. The population of Canada West (Upper Canada; present-day Ontario) was outstripping that of Canada East (Lower Canada; present-day Quebec), yet the political system gave equal representation to both sections of the province. George Brown’s Reform party demanded representation by population, which would have turned French Canadians into a permanent minority. This arrangement was categorically rejected by George-Étienne Cartier’s Bleus, who were in alliance with John A. Macdonald’s Liberal-Conservatives. As the Reform party became stronger in Canada West, the situation became increasingly unstable. Between 1861 and 1864 there were two elections, four administrations, and an atmosphere that was increasingly tense and acrimonious.

Seeking a way out, Brown proposed the creation of an all-party committee on Canada’s constitutional future – and, in June 1864, it reported in favour of federalism, either within Canada itself, or embracing British North America as a whole. Among the opponents was Macdonald, who preferred legislative union with a strong central government to a federal system. But Cartier had endorsed federalism, and without his support, Macdonald would have been politically isolated. Partly for this reason, and partly because he saw the possibility of a broader alliance with Conservatives such as Charles Tupper in the Maritimes, Macdonald quickly adjusted to new realities. Resisting any kind of union were the Rouges of Canada East, led by Antoine-Aimé Dorion: they feared that confederation would result in the assimilation of French Canadians. The Rouges remained on the side when Macdonald and Cartier’s Liberal-Conservatives and Brown’s Reformers came together in what would be known as the “Great Coalition” to pursue federalism.

While these events were taking place, plans were under way in the Maritimes for a September conference in Charlottetown, chaired by Prince Edward Island’s premier John Hamilton Gray (1811–87), to discuss the political union of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. Seizing the opportunity, the Canadians invited themselves to the meeting, and made a strong case for the union of all the British North American provinces. Many of them had visited Atlantic Canada that summer during a goodwill tour (which was dismissed by the anti-confederate Montreal journalist George Edward Clerk as “the Big Intercolonial Drink”). The conviviality continued throughout the Charlottetown conference, and contributed to an atmosphere of camaraderie in which new friendships were established. After four days of secret discussions, the delegates reached broad agreement on the principles of confederation, provided, as Brown wrote to his wife on 13 September, that “the terms of union could be made satisfactory.” To hammer out those terms, they agreed to meet again the next month in Quebec City.

There, over the course of three weeks, the delegates discussed the relationship between federal and provincial powers, forms of regional representation, the allocation of debts, assets, and taxes, the judicial system, the educational rights of Protestant and Roman Catholic minorities, and the linguistic rights of French Canadians. By the time they finished, the delegates from Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia had agreed upon the 72 resolutions that formed the basis of the new Dominion of Canada. The Prince Edward Island delegates rejected the terms, largely because they failed to address the demands of tenant farmers who wanted to buy out their landlords. Newfoundland, which sent two observers to the Quebec conference, opted to maintain its legislative independence. Prince Edward Island would join confederation in 1873; Newfoundland would join in 1949.

The work begun in Charlottetown and Quebec City was completed at a third conference, in London. Between early December 1866 and early February 1867, the Canadian delegates met with representatives of the imperial government to prepare the British North America Act, which was passed on 29 March 1867, and which came into effect on 1 July 1867. It was, declared Thomas D’Arcy McGee in the House of Commons on 14 November 1867, “the first Constitution ever given to a mixed people, in which the conscientious rights of the minority, are made a subject of formal guarantee.” Cartier had ensured that Quebec would exert full control over its legal, religious, educational, and cultural institutions. He and Macdonald were equally happy that the federal government would operate the main levers of political and economic power. And Brown rejoiced that Ontario was no longer subject to what he termed “French domination”; for him, confederation was as much about separating Ontario from Quebec as about building a new country.

The biographies included here are those of the key proponents of confederation at Charlottetown and Quebec City and those of the people who accepted, qualified, or rejected its terms – and who, in doing so, participated in a debate that echoes into the present.