Source: Link

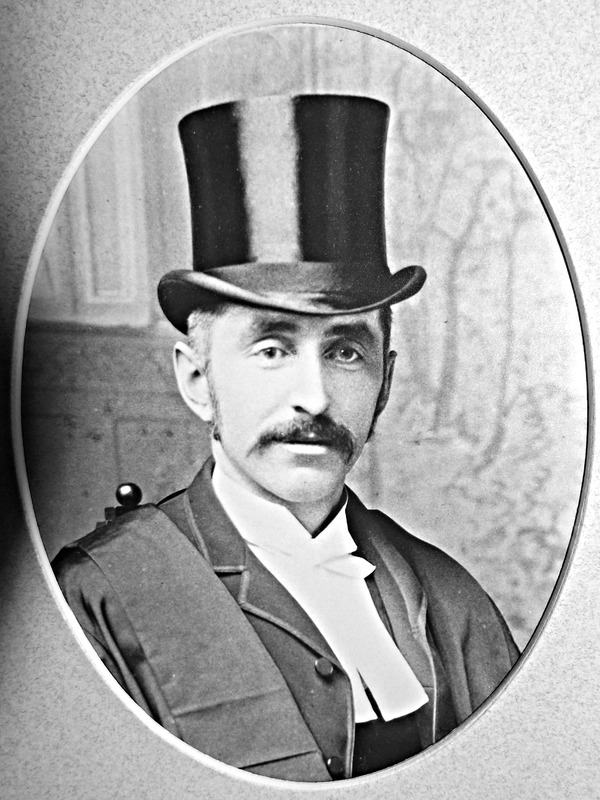

WHITE, ALBERT SCOTT, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 12 April 1855 in Sussex, N.B., son of James Edward White and Margaret Scott; m. 8 June 1892 Ida May Vaughan in St Martins, N.B., and they had one son; d. 17 March 1931 in Saint John.

Albert Scott White was a great-grandson of the fighting American loyalist who gave his name to Whites Cove, N.B. Destined by his father for a mercantile career, Albert was determined to become a lawyer. After graduating in 1873 with a ba from Mount Allison Wesleyan College (he would later serve on the governing body of his alma mater), he proceeded to Harvard law school. He received his llb in 1877 and was called to the New Brunswick bar the same year. In reference to his early days in court, he once remarked that it had seemed to him almost a joke that he was getting paid to do what he most liked to do. Throughout his 30-year career he practised in Sussex, then as now the centre of the province’s dairy industry; he was created a qc in 1894.

Subsequently appointed to the bench, White was but one of the judicial nominees in post-confederation New Brunswick whose path to advancement, in the words of historian D. G. Bell, “lay through partisan politics” [see Sir John Campbell Allen*]. Yet he was to prove unusual among this group because of his eminence as both a lawyer and a judge; in this regard he was a throwback to the prelapsarian meritocracy before confederation. White’s political career began with the official birth of the New Brunswick Liberal Party in the spring of 1886, when, a few days after his 31st birthday, he was elected as a Liberal for Kings County. A wunderkind of provincial politics, he was a member of the House of Assembly for 14 years, speaker of the house at age 35, and a minister at 38. A protégé of Premier Andrew George Blair*, White got his break in 1892 when the newly appointed solicitor general, Ambroise-D. Richard, did not win election and White was named in his stead. He retained office under James Mitchell* and went on to serve as attorney general and commissioner of public works in Henry Robert Emmerson*’s administration.

He failed, however, in both of his attempts to become an mp. The first was during the federal election of 1900 when Blair, then minister of railways and canals in the cabinet of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, moved from the riding of Sunbury and Queens to Saint John City. White resigned his safe seat in the provincial legislature to contest Blair’s old constituency but was defeated. White did not return to provincial politics. Instead, he kept busy as chair of the commission to revise the New Brunswick statutes; he also drafted, on Blair’s behalf, the Railway Act of 1903. His second unsuccessful bid for election to the House of Commons was in 1904, when he ran as a Liberal for the constituency of Kings and Albert.

His final political service came during the spring of 1907: he acted as co-counsel with William Pugsley*, the attorney general and premier, in the prosecution of Fredericton newspaper proprietor James Harvie Crocket*, charged with libelling Emmerson. After standing over for several months, the case was stayed in January 1908; later that month White was appointed puisne judge of the Supreme Court of New Brunswick. He had been offered the succession to Chief Justice William Henry Tuck* but declined; it went to senior puisne judge Frederick Eustache Barker, then aged 70, who entirely lacked White’s distinction. In 1906 the Judicature Act legislated changes that were to be made to the province’s court system, but reform would be deferred until 1913. That year the Conservatives, under James Kidd Flemming*, brought in an amended act which created the Supreme Court of Judicature, with appeal, trial, and chancery divisions; White was named a justice of the Court of Appeal. His Blairite Liberalism, however, would rob him of the chief justiceship in 1914, when Ezekiel McLeod was appointed, and again in 1917, when the post went to John Douglas Hazen. Partisan politics may have also denied White the opportunity to chair the two commissions of inquiry into the scandals that drove Flemming from office in 1914. Describing the candidates in a letter to Hazen, John Babington Macaulay Baxter*, who was soon to be attorney general, dismissed White as “impossible.” Responsibility for the commissions went instead to Harrison Andrew McKeown.

From 1918 to 1922 White chaired Ottawa’s Paper Control Tribunal (the other members were William Edward Middleton* and Charles Archer), set up under the War Measures Act [see Sir Robert Laird Borden] to regulate the price of newsprint. The Supreme Court of Canada reversed White’s judgement in Hetherington v. Security Export Company Limited; his greatest legal triumph followed in 1924, when the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ruled that administrative actions cannot be subjected to judicial review and reinstated his decision.

White was too much the instinctive lawyer ever to have reached the top of the greasy pole in provincial politics. The bench was his element, and in his 17 years as an appellate judge he was largely responsible for restoring the reputation of the New Brunswick judiciary. His enviable record and his legacy go some distance towards explaining why, in the 20th century, most Atlantic Canadian justices who served on the Supreme Court of Canada were from New Brunswick. In his time he was the most highly regarded jurist in eastern Canada. Had it not been Nova Scotia’s “turn” to send a puisne judge to the Supreme Court in 1924, White would have succeeded native New Brunswicker Francis Alexander Anglin (the post went to Edmund Leslie Newcombe instead).

Albert Scott White died suddenly in 1931 and was replaced on the bench by Baxter, who resigned from his position as premier to fill the vacancy. White’s son, Donald Vaughan (1895–1962), was a successful criminal defence lawyer in Halifax before returning to New Brunswick, where he became a county-court judge in 1945.

Kings County Record (Sussex, N.B.), 1887–1931. D. G. Bell, “Judicial crisis in post-confederation New Brunswick,” in Glimpses of Canadian legal history, ed. Dale Gibson and W. W. Pue ([Winnipeg], 1991), 189–203. D. M. G., “Review by Certiorari,” Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), 3 (1925): 47–50. B. J. Hibbitts, “A change of mind: the Supreme Court of Canada and the Board of Railway Commissioners, 1903–1939” (llm thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1986). Vital statistics from N.B. newspapers (Johnson), 1873–92.

Barry Cahill, “WHITE, ALBERT SCOTT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/white_albert_scott_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/white_albert_scott_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barry Cahill |

| Title of Article: | WHITE, ALBERT SCOTT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2015 |

| Year of revision: | 2015 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |