Source: Link

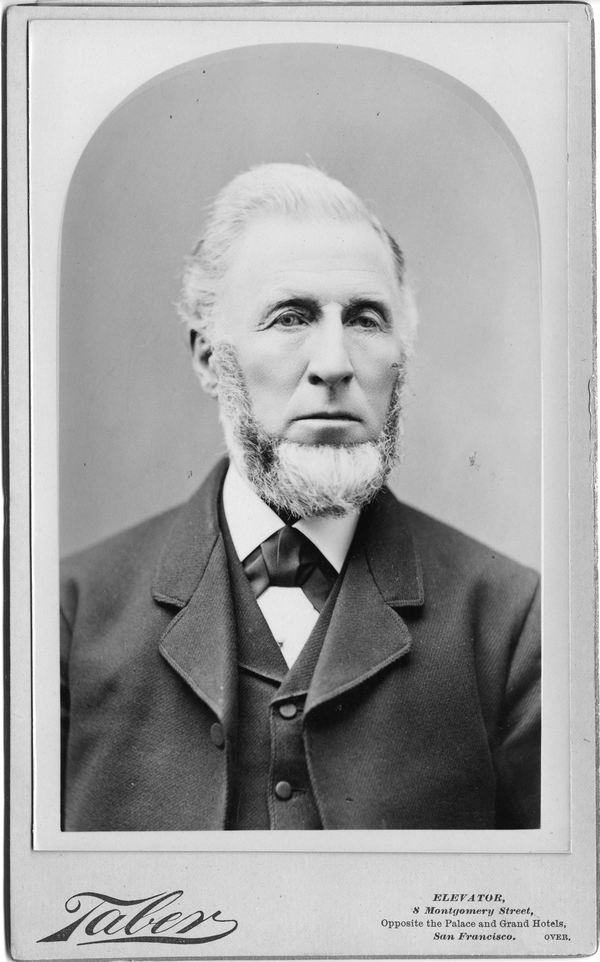

TODD, JACOB HUNTER, businessman and politician; b. 17 March 1827 near Brampton, Upper Canada, son of John Todd and Isabella Hunter; m. first 25 Jan. 1854, in Brampton, Anne Fox (d. 1866), and they had two sons and two daughters, of whom a son and a daughter survived childhood; m. there secondly 24 March 1873 Rosanna Wigley, and they had five sons, of whom three died young, and two daughters; d. 10 Aug. 1899 in Victoria, B.C.

According to descendants of Jacob Hunter Todd, his father, an Irish farmer who spent more time fox hunting than farming, immigrated to the United States in 1816 and was joined by his wife two years later. He worked in New York City at several trades before moving in 1820 to a farm in Trafalgar Township, Upper Canada, preferring, in the words of the Canada Christian Advocate, “life under British rule.” Little is known of the first three decades of Jacob’s life; he received some basic education and then worked on the family farm. Later he and a brother sold sewing-machines from house to house, travelling by horse and buckboard. It was a modest enterprise with modest returns.

Todd and his wife Anne moved to Victoria, Vancouver Island, in 1862, the year the town was incorporated. Jacob went first, arriving in May after a five-week journey by train across the United States and by steamer from San Francisco to Esquimalt, Vancouver Island. It is possible that he returned to Upper Canada later that year to accompany his wife and children to the west; their two-year-old daughter apparently died on the ship from San Francisco.

Within two weeks of his arrival in May, with a capital of $575, Todd had embarked on his first venture, importing 296 bushels of potatoes from Seattle, which yielded a net profit of $148 on his investment and expenses of $356. His next notable undertaking was a contract to build a fence around the property of Governor James Douglas*. Using unbroken staves from discarded barrels, he was able to obtain the materials virtually free of charge and thus made a respectable profit. The fence remained a source of great pride to Todd even when he had become one of the wealthiest citizens of the colony. More important for his future, however, was the opportunity to make the acquaintance of the governor. Douglas was from the outset well disposed toward Todd, regarding him as a man of initiative, attached to British institutions.

In 1863 Todd went to the Cariboo district on the mainland, where he established a general store at Barkerville, the heart of the gold-mining community [see William Barker]. In the 1868 fire that destroyed the town, he lost about $10,000 worth of goods and buildings, but he began at once to rebuild. Known for his fairness, Todd, who chose as the motto for his store “Live and let live,” was popular among the miners, both white and Chinese. His store flourished, and he was willing to grub-stake miners and prospectors in whom he had confidence. Despite his frequent claims that more gold went into the ground than ever came out of it, he speculated with considerable shrewdness in gold claims and properties, although he himself never became a miner. No doubt he owed his success in speculation partly to his position as a merchant, since debts were sometimes settled in claims.

Todd spent the winters with his family in Victoria, but returned each spring to the gold-fields. When the Cariboo gold began to peter out, he left Barkerville in 1873 to establish new enterprises on Vancouver Island and the coast. On Wharf Street in Victoria he opened a dry-goods and outfitting store that served as ship-chandlery to many sealing vessels, and he also operated a grocery store on lower Yates Street. In 1875 he set up J. H. Todd, a wholesale grocery firm, to supply goods to the interior of the mainland. Two years later he took his son Charles Fox into the company, renaming it J. H. Todd and Son. Shortly after his departure from Barkerville in 1873, Todd had returned briefly to Ontario to remarry, having been widowed seven years earlier. His new wife, a 35-year-old schoolteacher from Brampton, was not allowed by Todd to continue teaching, but she became active in the community in other ways, notably as one of the first of the serious amateur gardeners for whom Victoria became known, and as a staunch supporter of St John’s Church (Anglican).

The most important of Todd’s ventures after leaving the Cariboo was his entry into the salmon-canning industry. Canneries had been operating in British Columbia since the early 1870s and were becoming increasingly important in the economic life of the province toward the end of the decade [see Alexander Ewen*]. J. H. Todd and Son’s trademark “Horseshoe” brand was the first to be registered (1881). The company, together with a number of other investors, purchased the Richmond Cannery on the Fraser River in 1882 and built the Beaver Cannery in 1889; it would eventually own five canneries on the coast, including the largest, the Empire Cannery at Esquimalt, purchased in 1906. Todd’s success was owing partly to the business skills he had developed in other fields. For instance, he understood advertising, and when salmon canners had difficulty selling red sockeye salmon, he began an extensive advertising campaign using the slogan “This salmon is guaranteed not to lose its colour when canned.”

Todd was also one of the first to establish large-scale commercial fish traps. Of the four ultimately operated by his company, the one near Sooke survived until the mid 1950s, probably the only early commercial trap on the coast to last so long. Todd and his sons Charles Fox and Albert Edward, both of whom became active in the business, chose the locations well, and the traps were very profitable. The Todds were despised by those who fished from boats, on account of the efficient manner in which they harvested high-quality fish. A considerable number of the approximately 100 men employed at Sooke were guards hired to prevent vandalism. In the late 1880s, when salmon runs were declining, new federal fishery regulations were introduced [see Thomas Mowat], which meant that cannery operators and independent fishermen competed for fishing licences; many months and much money would be spent by the Todds lobbying in Ottawa for concessions to the family company.

With characteristic energy, Todd adopted advances in the fishing industry. He owned scores of small fishing boats, which he leased to fishermen in return for a percentage of the catch. Tugs were purchased to tow the boats from the canneries or villages to the fishing grounds. Steam vessels were constructed to take the catch to more distant canneries. Markets were developed in Great Britain and Europe, and his “Horseshoe” brand won prizes at London’s Crystal Palace exhibition and at other world fairs. Through the efforts of the Todds as well as others in the industry, canned salmon became a popular food, particularly in Great Britain, where it was known as “the working man’s feast.”

During the 1880s and 1890s Todd invested in real estate much of the profits yielded by his business; he owned commercial and residential land in most of the cities of the province, especially in Vancouver, and he had substantial holdings of farm land in the Fraser valley. After his death in 1899 it was reported in the press that his estate was the largest ever probated in British Columbia.

In addition to his business interests, Todd took an active part in public life. He ran unsuccessfully in the Cariboo for a seat in the House of Commons in the election that followed British Columbia’s entry into confederation in 1871. Before the elections of 1878 he sought and won the Liberal-Conservative nomination in Victoria, but when Sir John A. Macdonald lost his seat in Ontario, Todd gave up the nomination to the party leader. In return he obtained a promise of a graving dock for the province, which was eventually built at Esquimalt, to the chagrin of the residents of Vancouver. He served as alderman in Victoria for two years and was among the founders of its board of trade.

Jacob Hunter Todd emerges from his few surviving letters as a stern man in the Victorian mould, whose instructions to his sons at school in Upper Canada are filled with exhortations to behave in a pious and proper manner and, in particular, to refrain from reckless expenditures. He is believed to have been deeply disappointed when his daughter Sarah Holmes eloped with a fashionable Victoria physician, Dr John Chapman Davie (brother of premiers Alexander Edmund Batson Davie* and Theodore Davie). Although he was described as a hard businessman, Todd was probably no more so than most of his peers. Certainly he was honest in his business and personal affairs, and he was generous to civic causes and the church. He was noted for helping others in difficulty, and the fact that his loans were generally repaid is a tribute to his good judgement of character; there is no evidence that he took advantage of the misfortune of others by requiring onerous repayment terms. His attitude toward Chinese immigrants was generous and liberal, contrary to the popular views of his day. He was held in high esteem by his contemporaries, who regarded him, according to his obituary in the Daily Colonist, as “one of those who made Victoria her reputation as the commercial center of the Pacific Northwest.”

[Information for the preparation of this biography was provided by Mrs J. W. [Sheila] Anderson of Victoria and Bridget Bartlett Todd (Mrs Fialkowska) of Senneville, Que. d.a.]

British Columbia Geneal. Soc. (Richmond), File information on J. H. Todd. Univ. of B.C., Special Coll. (Vancouver), M634 (Todd and Sons Company, Ltd., records). Victoria City Arch., File information on J. H. Todd. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1893, no.10c. Canada Christian Advocate (Hamilton, [Ont.]), 8 March 1854. Daily British Colonist and Victoria Chronicle (Victoria), 6 Jan., 27 Oct. 1863; 28 April 1872. Daily British Whig, 10 March 1873. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 11 Aug. 1899. B.C. directory, 1863, 1877–78, 1883. Cicely Lyons, Salmon & our heritage: the story of a province and an industry (Vancouver, 1969). H. W. McKervill, The salmon people: the story of Canada’s west coast salmon fishing industry (Sidney, B.C., 1967). Daily Colonist, 5 Nov. 1961.

David Anderson, “TODD, JACOB HUNTER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/todd_jacob_hunter_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/todd_jacob_hunter_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Anderson |

| Title of Article: | TODD, JACOB HUNTER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |