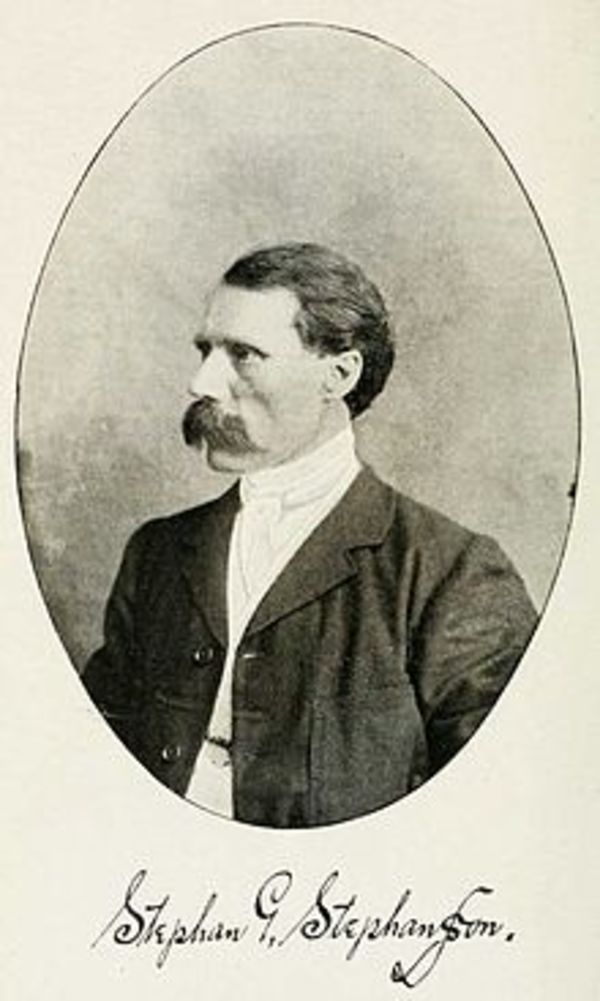

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

STEPHANSSON, STEPHAN GUDMUNDUR (Stefán Guðmundsson), farmer and poet; b. 3 Oct. 1853 near Víðimýri, Iceland, son of Guðmundur Stefánsson and Guðbjörg Hannesdóttir; m. 28 Aug. 1878 Helga Sigríður Jonsdóttir in Wisconsin, and they had five sons and three daughters; d. 10 Aug. 1927 near Markerville, Alta.

Stefán Guðmundsson was born on a rented farm, Kirkjuhóll, in the northern Icelandic region of Skagafjörður. Educated at home, during his teen years he practised verse making, following old skaldic traditions. If poetry was his avocation, farming was his vocation; in Iceland his work was limited to raising sheep. When he immigrated to the United States in 1873 with his family and a small contingent of Icelanders, American officials, misunderstanding his father’s patronymic of Stefánsson, gave the name Stephansson to the entire family. Later in life, Stephan chose to sign his name Stephan G. Stephansson, although he still used his native name of Stefán Guðmundsson among his Icelandic friends. The family settled first in Wisconsin, where Stephan learned the rudiments of tilling the soil and married Helga, his first cousin, in 1878. In 1888, in Garðar (Gardar, N.Dak.), he incurred the wrath of many of his church-going countrymen when he helped organize the Hins Islenzka Menningarfelags (Icelandic Cultural Society), a debating club based on the Society for Ethical Culture founded by prominent freethinker Felix Adler in New York City.

A collapse of the grain market forced the family’s final move, in 1889, to the Alberta district of the North-West Territories. Stephansson would become a naturalized citizen five years later. Homesteading along the Medicine River north of Calgary, on SW10-T37-R2-W5, he raised cattle and sheep. He was the first secretary of the joint-stock company formed by farmers in 1899 to support a dominion government creamery in nearby Markerville. His reliance on livestock, however, did not preclude his planting of various grains, and in 1900 he was the first member of the Icelandic settlement to harvest rye. In addition to the post he held with the creamery company, he was a justice of the peace and a member of the local school board.

Although Stephansson had written some poetry before moving to Alberta, it was during his years on the Canadian prairies that he honed his craft, marrying traditional Icelandic metre (as well as experimenting with new metres) to the philosophy of the American freethinkers. His long view of history and man’s place in it is evident in his poem “Staddur a grothrarstoth” [At the forestry station] of 1917:

Monuments crumble. Works of mind survive

The gales of time. Men’s names have shorter life.

Forgetful time may mask where honor’s due

But mind’s best edifices live and thrive.

Stephansson composed and read mostly at night, and much of his correspondence pertains to literary and intellectual interests. He used verse and prose to criticize the Icelandic Lutheran Church, whose dogma and schisms he viewed as a threat to Icelandic culture. Among others, he sparred with the Reverend Jón Bjarnason*, whom he nonetheless regarded as a true Icelandic nationalist. Another explosive issue for west Icelanders (the designation for those who had come to North America) was World War I. Stephansson was open and vehement in his opposition to it and to Icelandic Canadian involvement. His Vígsloða [The trail of war] is a collection of pacifist poems published in Reykjavík, Iceland, in 1920, only some of which had appeared during the war. Copies sold in Winnipeg brought strong denunciation. Politically he supported the United Farmers of Alberta and he flirted with Marxism, which he viewed as the logical theory of scientific socialism.

Despite controversy, Stephansson was well respected as a poet. Writing only in Icelandic, he excelled at intricate metaphors, wonderful imagery, and neologism. Much of his verse romanticized Iceland and its history; “Þó þú langförull legðir” [Song to Iceland] of 1903 has been set to music and is considered an important national song. The narrative “A ferð og flugi” [En route] of 1898, an excellent example of his descriptive ability, tells of the immigrant experience crossing the prairies by train in mid winter:

The bluish-white tide of the snow had engulphed

Each hillock and hollow as well,

And the frost-haggard trees were like pallid, grey ghosts

From the pale, frozen forests of hell.

Other themes include the value of hard work, adversity as challenge, and the transience of life. Much of his verse dwells on the beauty of the Alberta landscape, and in Iceland he became known as Klettafjallaskadið, or the poet of the Rocky Mountains. The first three volumes of his collected works, Andvökur [Sleepless nights], were published in 1908–9 in Winnipeg. Stephansson’s bitter satire and his use of archaic words and convoluted style generated criticism, but Andvökur also brought new exposure and popularity, which led to reading tours of North Dakota, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan in 1908–9 and the west coast in 1913. The greatest honour came in 1917 when the people of Iceland invited him to return for a four-month tour; he was regarded by many there as the best Icelandic poet to have emerged since the 13th century. With the publication of two more volumes in 1923 and a sixth posthumously in 1938, his output fills more than 2,000 pages, making him one of Canada’s most prolific poets.

Stephansson suffered a stroke in 1926 and he died at his farm a year later. He was buried in the private Kristinsson cemetery near Markerville. In 1976 Alberta declared his homestead a provincial historic resource.

A complete bibliography of the works of Stephan Gudmundur Stephansson can be found in the author’s study, written under the name J. W. McCracken, Stephan G. Stephansson: the poet of the Rocky Mountains ([Edmonton], 1982). Translated examples of his writings are in [S. G. Stephansson], Selected prose & poetry, trans. Kristjana Gunnars (Red Deer, Alta., 1988), and Selected translations from “Andvökur,” ed. Jane Ross (Edmonton, 1982).

LAC, RG 15, DIII, 10, 144, f.25 (mfm. at PAA). Private arch., Edwin Stephansson (Markerville, Alta.), Stephan G. Stephansson papers. Univ. of Manitoba Libraries, Elizabeth Dafoe Library (Winnipeg), Icelandic Coll., Stephan G. Stephansson’s book coll. Peter Carleton, “Tradition and innovation in twentieth century Icelandic poetry” (phd thesis, Univ. of California, Berkeley, 1967). F. S. Cawley, “The greatest poet of the western world: Stephan G. Stephansson,” Scandinavian Studies and Notes (Menasha, Wis.), 15 (1938): 99–109. M[agnús] Einarsson, “Oral tradition and ethnic boundaries; ‘West’ Icelandic verses and anecdotes,” Canadian Ethnic Studies (Calgary), 7 (1975), no.2: 19–32. Stefán Einarsson, A history of Icelandic literature (New York, 1957). V. J. Eylands, Lutherans in Canada, intro. F. C. Fry (Winnipeg, 1945). J. C. F. Hood, Icelandic church saga (London, 1946). Icelandic lyrics: originals and translations, ed. Richard Beck (Reykjavík, 1930). Skuli Johnson, “Stephan G. Stephansson (1853–1927),” Icelandic Canadian (Winnipeg), 9 (1950–51), no.2: 9–12, 44–56. Watson Kirkconnell, “Canada’s leading poet: Stephan G. Stephansson (1853–1927),” Univ. of Toronto Quarterly, 5 (1935–36): 263–77; The North American book of Icelandic verse (New York and Montreal, 1930). W. J. Lindal, The Icelanders in Canada (Ottawa and Winnipeg, 1967). Kerry Wood, The Icelandic-Canadian poet, Stephan Gudmundsson Stephansson, 1853–1927: a tribute (Red Deer, [1974]).

Jane Ross, “STEPHANSSON, STEPHAN GUDMUNDUR (Stefán Guðmundsson),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stephansson_stephan_gudmundur_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stephansson_stephan_gudmundur_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jane Ross |

| Title of Article: | STEPHANSSON, STEPHAN GUDMUNDUR (Stefán Guðmundsson) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |