Source: Link

SHEPPARD, EDMUND ERNEST, journalist and author; b. 29 Sept. 1855 in South Dorchester Township, Elgin County, Upper Canada, only son of Edmund Sheppard and Nancy Bently; m. 8 Oct. 1879 Melissa Culver in Mapleton, Ont., and they had one son and three daughters; d. 6 Nov. 1924 near San Diego, Calif.

In his 1888 novel Widower Jones, a melodramatic tale of a prodigal’s conflict with his clergyman father, Edmund E. Sheppard described sons of the manse as bad actors, the worst miscreants. He perhaps drew upon personal experience for this and other judgements. Indeed, his whole career (filled as it was with sensational and unorthodox behaviour) might be interpreted as a lifelong rebellion against his own religious upbringing.

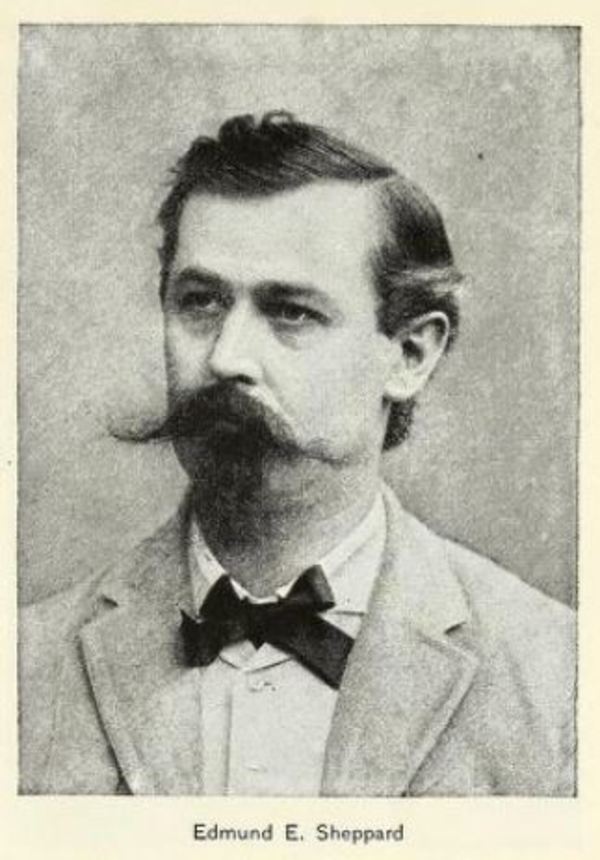

Sheppard’s father had emigrated from England in 1843. After several years as a teacher and then as a superintendent of schools, he became one of the first Canadian ministers in the Disciples of Christ. Edmund Jr received his early education in the St Thomas area and subsequently began medical studies at Bethany College in West Virginia, an institution which his father had attended before him. He apparently dropped out and headed down to Texas and Mexico, reportedly spending several years as a cowboy and stagecoach driver. After his return to Canada in 1878 he regularly affected the cowboy style: a slouch hat, fine Spanish leather riding boots, string tie, handlebar moustache, and goatee. His penchant for chewing tobacco and strong drink probably also dated from those years in the southwest.

Back in Ontario, he turned to journalism, first in London and St Thomas and then with the Toronto Daily Mail, under managing director Christopher William Bunting*. Appointed editor-in-chief of John Riordon*’s newly established Toronto Evening News in 1883, he would become its proprietor later that year. There he gathered around him a bold and somewhat Bohemian crew of writers anxious to stir up the complacent Toronto newspaper world. The News had two main characteristics: radicalism and sensationalism. In politics it advocated an independent, republican Canada where the elective principle would be applied to virtually all public offices, and church and state would be completely separate. The Knights of Labor, the new trade union that burgeoned briefly in the late 1880s [see Alexander Whyte Wright*] and whose intellectual leader, Thomas Phillips Thompson*, acted as assistant editor of the News, had the paper’s full support. All the employees joined the union and in 1886 marched in the Labour Day procession wearing white plug hats. In 1887, with labour backing, Sheppard contested the Toronto West seat in the dominion parliament, losing narrowly to Frederick Charles Denison*. He was subsequently unsuccessful in campaigns for the provincial legislature (1890) and, running against Robert John Fleming, for the office of mayor of Toronto (1893).

His paper’s sensationalism took a variety of forms. Printed on pink stock, it concentrated on local news, carried mildly salacious gossip, and serialized novels (Sheppard’s first fiction, “Dolly,” appeared there). Short paragraphs, pungent language, and racy headlines were designed to catch the reader’s attention. But sensationalism sometimes had a hard edge. Not surprisingly, given Sheppard’s membership in the Orange lodge, the News treated Roman Catholics and French Canadians rudely. In 1885 a story written by Louis P. Kribs* cast aspersions on Montreal’s 65th Battalion of Rifles (Mount Royal Rifles), suggesting cowardice during the North-West rebellion. Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph-Aldric Ouimet*, the unit’s commanding officer and a rising young Conservative mp, brought a libel action against the News and its editor. The charge, and Sheppard’s efforts first to avoid trial in Montreal and then to resist making the apology demanded by the court for the unfounded story, was a minor cause célèbre for over two years. In the end Sheppard lost, apologized, promised to pay a fine and court costs, and, as it turned out, was forced to relinquish control of the financially floundering News. The experience doubtless confirmed his francophobia.

As the trial dragged to its finale, Sheppard joined two others, Walter Cameron Nichol and William E. Caiger, in establishing Saturday Night, whose first issue appeared on 3 Dec. 1887. At the new weekly Sheppard put most of his radicalism behind him. Where the News had aspired to the role of a “people’s paper,” Saturday Night sought to provide “social intelligence” to a culturally aware, socially conservative readership. During the two decades of Sheppard’s editorship – in this period he was also briefly editor of the Toronto Star [see Sir William James Gage] – the magazine featured well-written articles on literature, music, art, politics, business, and religion. Sheppard encouraged many young writers, including women such as Kate Eva Yeigh [Westlake*], with whom he had been associated in St Thomas, Agnes Mary Scott, and Kathleen Blake Watkins [Catherine Ferguson*], to contribute. In his own regular column (written under the Spanish pseudonym Don), he often questioned received opinions. He especially enjoyed tilting at clerical windmills. During his vigorous campaign for Sunday streetcars in Toronto in the 1890s, he claimed that “the preachers are trying to keep a corner on the Sunday, they are afraid if any other attraction is offered their place of worship will be deserted.”

If Sheppard’s earlier radicalism subsided at Saturday Night, his hostility to French Canadians remained untamed. He repeatedly drew parallels between Canada and the pre-Civil War United States, with Quebec cast in the role of the South. Any attempt to extend the French language beyond the Ottawa River – Canada’s Mason-Dixon Line – would be met with force, he contended. For him Quebec was a sink of clerical domination, political corruption, and linguistic aggressiveness. “Why beat about the bush?” he asked rhetorically. “What are we here for? Why did [James Wolfe*] take the trouble to fight with [Louis-Joseph de Montcalm*]? Was is not to conquer Canada? Was it not to make the Anglo-Saxon supreme? . . . We can never become a nation if we continue a dual language.” Though the bellicose tone would moderate in later years, Sheppard’s ethnocentrism never entirely dissipated.

Despite his repeated criticism of clericalism, Sheppard’s writing, Hector Willoughby Charlesworth* observed, frequently had “an underlying religious vein.” Certainly that was true of the three unmemorable novels he published in the 1880s. Each one criticized established Christianity, emphasizing the gap between doctrine and action, yet each also displayed sympathy for what Sheppard called “the spirit of Christ’s teachings.” He apparently shared the theological liberalism so popular among his contemporaries, which inclined some to the Social Gospel. In his case, after ill-health forced his retirement and departure for California in 1906, religious liberalism led down a path to what is sometimes called “mind cure” or “New Thought.”

Sheppard’s 1915 book, The thinking universe, presented a hodgepodge of cultish ideas purporting to demonstrate that Christian Science was the highest stage of religion. Its aim, he wrote, was “to change Man’s attitude towards Infinity; to uplift him into a consciousness of being his own Infinity; to stir his Reason into grasping the fact that he is perfectly equipped for every emergency; to point him to the power he has within him to grapple with sickness and sin.” The nascent religious liberalism of the writer whom John Wilson Bengough had once called “The Journalistic Cowboy” had, logically enough, reached senescence in the power of positive thinking.

He died, after a lengthy illness, near San Diego, on 6 Nov. 1924.

Edmund Ernest Sheppard is the author of Dolly, the young widder up to Felder’s (Toronto, 1886); Widower Jones, a faithful history of his “loss” and adventures in search of a “companion”; a realistic story of rural life (Toronto, 1888); A bad man’s sweetheart (Toronto, 1889); and The thinking universe; reason as applied to the manifestations of the infinite (Los Angeles, 1915).

AO, RG 80-5-0-79, no.2197. NA, RG 31, C1, 1901, Toronto, Ward 3, div.35: 20. News (Toronto), 1883–87. Christopher Armstrong and H. V. Nelles, The revenge of the Methodist bicycle company: Sunday streetcars and municipal reform in Toronto, 1887–1897 (Toronto, 1977). H. [W.] Charlesworth, Candid chronicles: leaves from the note book of a Canadian journalist (Toronto, 1925). Ramsay Cook, “An epitaph for Edmund Sheppard and others,” in his Canada, Quebec, and the uses of nationalism (Toronto, 1986), 175–83. Russell Hahn, “Brainworkers and the Knights of Labor: E. E. Sheppard, Phillips Thompson and the Toronto News, 1883–1887,” in Essays in Canadian working class history, ed. G. S. Kealey and Peter Warrian (Toronto, 1976), 35–57. Paul Rutherford, A Victorian authority: the daily press in late nineteenth-century Canada (Toronto, 1982). Saturday Night (Toronto), 1887–1906; 22 Nov. 1924: 2.

Ramsay Cook, “SHEPPARD, EDMUND ERNEST,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sheppard_edmund_ernest_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sheppard_edmund_ernest_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ramsay Cook |

| Title of Article: | SHEPPARD, EDMUND ERNEST |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |