Source: Link

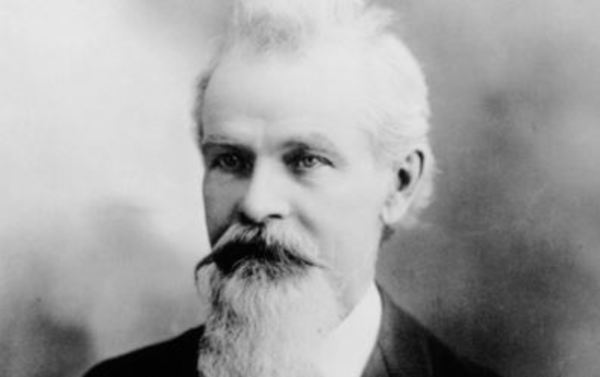

O’DONOGHUE, DANIEL JOHN, printer, trade-union leader, politician, editor, and civil servant; b. 1 Aug. 1844 in Listry, near Killarney (Republic of Ireland), eldest son of John O’Donoghue and Catherine Flynor (Flynn); m. 15 Sept. 1870 Marie-Marguerite Cloutier in Ottawa, and they had 11 children, of whom 3 daughters and 5 sons survived; d. 16 Jan. 1907 in Toronto.

Daniel J. O’Donoghue immigrated to Canada with his family in 1852. The death of his father led to his apprenticeship to an Ottawa printer at age 13. Possessed of little or no formal schooling, the young Dan became a crucial part of the family economy, especially after his brother Morris migrated to the United States to enter the Union army during the Civil War. While serving his apprenticeship, O’Donoghue joined the volunteer First Fire-Brigade as a lamp-boy in 1860 and took part in the St Patrick’s Literary Society. After becoming a journeyman printer, he left Ottawa in the mid 1860s and worked for a time in Buffalo, N.Y., where he joined the National Typographical Union. Following a brief return to Ottawa, he departed for about a year on the customary tramp of young journeymen printers; it took him to Cleveland, Milwaukee, Chicago, St Louis, Memphis, and New Orleans. In 1866 he went back to Ottawa, took a compositor’s case at the Times, and helped to organize Ottawa Typographical Union, Local 102 of the NTU, which would become the International Typographical Union three years later.

The Ottawa union fought its first major battle in November 1869, when it struck the Ottawa Citizen after the paper’s owner tried to cut the rates of compositors working on a recently obtained government-printing contract. The printers prevailed and succeeded in maintaining their rate. The following year O’Donoghue married the daughter of fellow Times compositor and printers’ union leader Georges Cloutier. Marriages within the craft were common; less usual was the linkage of Irish and French Canadian Roman Catholics. In O’Donoghue’s case this interethnic marriage would later aid his political career.

O’Donoghue established himself as an important labour leader in Ottawa and beyond during the workers’ upsurge of the early 1870s in Canada. He first came to prominence in the aftermath of the Toronto printers’ strike and the arrest of union leaders, among them John Armstrong, in the spring of 1872. O’Donoghue and stonecutter Donald Robertson successfully lobbied Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* to persuade him to introduce legislation equivalent to the statute recently passed in Britain legalizing trade unions. The Canadian act would allow Macdonald’s Liberal-Conservative party to parade as the workingman’s friend for the next two decades. In December 1872 O’ Donoghue and Robertson played leading roles in founding the Ottawa Trades Council, a central body for the city’s unions; O’Donoghue was elected secretary in 1872 and president the following year.

In 1873 O’Donoghue, now also president of the Ottawa Typographical Union, led a bitter strike for a nine-hour day, which Toronto printers had gained the year before. The strike ended in failure when employers imported foreign printers and trained women as compositors to replace the strikers. This experience undoubtedly helped shape O’Donoghue’s concern about the role of immigrant workers and may also have sharpened his consciousness of the situation of female workers. For part of the strike he was actually in Toronto attending the founding meeting of the Canadian Labor Union, the country’s earliest central labour organization. At the convention he served on the constitutional and printing committees and was elected first vice-president; he would be re-elected in 1874 and 1875. In 1873 the ITU met in Montreal, and O’Donoghue, the delegate of Ottawa Local 102, was elected to its executive committee.

In January 1874 the Ottawa Trades Council decided to run a workingman’s candidate in the provincial by-election in Ottawa occasioned by the resignation of prominent Roman Catholic politician Richard William Scott*. A nomination meeting chose O’Donoghue but only after considerable partisan opposition led by former ally Donald Robertson. The official Liberal-Conservative candidate eventually withdrew, at least passively in support of O’Donoghue, who scored a convincing victory over the Reform nominee. There can be little doubt that O’Donoghue’s ability to appeal to both Irish and French Canadian Catholics, on account of his religion and marriage, contributed to his success. Returned as an independent, workingman’s candidate, he merits recognition as the first labour member of a Canadian provincial legislature.

Despite the tacit electoral support of the Liberal-Conservatives, O’Donoghue ended up in his first year in parliament supporting most of the program of Oliver Mowat’s Reform government, which included pro-labour legislation regarding trade-dispute arbitration, mechanics’ liens, and employee profit-sharing. In the general election of 1875, however, he found himself opposed by both parties. In a narrow, three-way race he none the less emerged victorious; his return was no mean feat since his opponents were Ottawa mayor John Peter Featherstone, running as a Reformer, and former federal cabinet minister John O’Connor*, a Tory. O’Donoghue’s electoral platform in both campaigns closely paralleled the aims of the Canadian Labor Union. He pledged to work for an extension of the franchise, better mechanics’ lien legislation, the abolition of convict labour, and an immigration policy that restricted the entry of skilled workers. Of more significance to his Ottawa constituents, he also promised to act in the interest of the lumber industry and press for an extension of public works. Although in the legislature his voice was “muffled” in 1874, in his second term he actively promoted restricted immigration and extension of the male franchise, while opposing both convict and contract labour. It should be noted that, though he fought for the vote for male workers, he voted against suffrage for propertied women at the municipal level.

In the election of 1879 O’Donoghue suffered defeat by a wide margin. Mowat had recommended that Ottawa Reformers nominate him, but they refused to do so and consequently the Tory candidate won. No doubt the demise of the CLU, the OTC, and many local unions during the deep depression of the 1870s left O’Donoghue without his former support. As a result of his electoral failure, he moved to Guelph, where he edited a paper for a time.

Settling in Toronto in November 1880, O’Donoghue returned to the case as a compositor at the World. A member of Toronto Typographical Union, Local 91 of the ITU, he again began to play an important, role in the labour movement. The TTU commenced discussions in the spring of 1881 about reorganizing a city central; this initiative received significant impetus from the convention of the ITU in Toronto in June. That August delegates from a number of Toronto unions met and founded the Toronto Trades and Labor Council. Almost from its inception, and for the next 19 years, O’Donoghue chaired its legislative committee, which became his main platform for promoting his personal vision of labour reform. He was especially critical of the federal government’s National Policy and immigration policy. “Protection for labour as well as protection for capital” was his rallying call. O’Donoghue initiated a policy of scrutinizing the actions of Canadian immigration agents in the British Isles and, under his guidance, the legislative committee circulated petitions and literature to unions across Canada. Such enterprise, plus his voluminous correspondence with British newspapers and trade unionists, projected the TTLC beyond local significance.

Of at least equal importance for Toronto workers was the arrival in 1882 of the Knights of Labor, who were to become in the ensuing decade the crucial institution in a remarkable social movement that brought workers in central Canada to the fore in the nation’s political debate. The key element in the Knights’ success was their innovative aim to organize the entirety of the working class. Building on the insights of skilled-craft unionists who in the 1870s had seen their unions defeated by mechanization, the order viewed craft and social distinctions as divisive. Ontario workers, male and female, Catholic and Protestant, skilled and unskilled, black and white, joined the order in masses. Particularly notable was the founding in Toronto of Excelsior Local Assembly 2305 in October 1882. It quickly became the organizational and theoretical centre for the rapidly expanding order in central Canada. As members, O’Donoghue and other labour leaders with experience from the 1870s, such as tailor Alfred F. Jury*, painters Charles March and John W. Carter, and journalist Thomas Phillips Thompson*, plotted the strategies that would hold sway for the next decade or more. Their major achievement was the founding of a new central body, the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada, which first met in Toronto in the fall of 1883. Initiated by the Toronto Trades and Labor Council, especially by O’Donoghue and the legislative committee, the TLC welcomed the membership of both unions and local assemblies of the Knights. The success of O’Donoghue and his colleagues in achieving such integration in the TLC, and then in the TTLC and other city centrals, minimized for a time the conflict between the local assemblies and unions that seriously undermined the order in the United States.

O’Donoghue informally functioned as the Canadian lieutenant of Terence Vincent Powderly, the order’s leader in North America. In that role he carried out important negotiations with Catholic bishops to ensure that they would not follow the lead of those conservative American and Quebec prelates who had denounced the order because of its status as a secret society. He first tackled Toronto’s archbishop, John Joseph Lynch*, on this subject in 1884 and won his support. The hostility of Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau* of Quebec led to difficulties in 1886 and O’Donoghue was given the task of visiting bishops Joseph-Thomas Duhamel of Ottawa and Édouard-Charles Fabre* of Montreal in an attempt to straighten out the matter. Later that year he also visited the papal ablegate seeking to explain the order. The eventual papal decision to agree with other American bishops that there was no incompatibility between Catholicism and the order owed much to O’Donoghue’s lobbying, especially with Lynch, who supported these bishops.

For three years everything went well for the order and for O’Donoghue and “the boys from 2305,” as he referred to his colleagues in his correspondence with Powderly. Labour candidates ran in the provincial election of 1883 in the ridings of east and west Toronto on a program worked out by the TTLC. Although both lost, one took 48 per cent of the vote. More impressive, in January 1886 a labour and social-reform alliance was able to secure the selection of William Holmes Howland* as mayor over incumbent Alexander Henderson Manning, whose connection to the Tory party and especially to the Toronto Daily Mail had alienated labour.

By early 1886 O’Donoghue and the members of Local Assembly 2305 had established their leadership within the TTLC, the TLC, and the Knights, and in the process had broken Tory control of Toronto’s working-class vote. Throughout the year the Knights continued to grow and fought two important strikes, at Toronto’s largest factory, the agricultural-implements works of Hart Almerrin Massey*, and against the Toronto Street Railway. For the Tories the railway battle caused even more difficulties because the owner of the franchise was prominent Conservative senator and cabinet minister Frank Smith. In the light of these problems in Toronto and with the Knights growing nationally, Sir John A. Macdonald set up a royal commission on the relations of labour and capital [see James Sherrard Armstrong*]. His attempt to assuage Toronto workers failed, however, when he appointed to it Samuel R. Heakes, a one-time labour candidate whose appearance on Tory platforms in the provincial election of December 1886 earned the enmity of Toronto labour.

The second and less formal Tory strategy for regaining the political loyalty of Ontario labour revolved around Alexander Whyte Wright*. Wright was a journalist and National Policy advocate who purchased the Toronto edition of the Palladium of Labor in 1886 and reissued it as the Canadian Labor Reformer. He thus set himself up in direct conflict with O’Donoghue, who had started the Labor Record that year. Wright’s major aim apparently was to counter the political success of Local Assembly 2305. His first accomplishment was the creation in May 1886 of a Knights’ city central, Toronto District Assembly 125. O’Donoghue had bitterly opposed this organizational change, for he feared the potentially divisive impact of a central parallel to the TTLC. Instead, he had favoured the creation of a provincial assembly, which would have filled a gap between city centrals such as the TTLC and the national TLC.

Wright’s second achievement, which again brought him into direct conflict with O’Donoghue, came when he skilfully manipulated nationalist sentiment for a separate Canadian order of Knights independent of American control. This movement was co-opted by Powderly at the general assembly of 1887 when he initiated two provincial assemblies and recommended a Canadian legislative committee. After consulting O’Donoghue, he appointed Alf Jury of 2305, George Collis of Hamilton, and John T. Redmond of Montreal. Though O’Donoghue appeared to have regained control, his advantage was only momentary. In late July Powderly appointed Wright as a lecturer under the order’s educational fund. Wright’s triumph was completed at the general assembly of 1888, when he won election to the general executive board and, more important, gained Powderly’s trust. As a result, he took control of recommendations for the Canadian legislative committee and immediately replaced Jury and the others with his own allies. The partisan battles that ensued helped to weaken the order, which was already in precipitous decline in Ontario. Wright’s manoeuvres of the legislative committee also resulted in the gradual displacement of the order as a central lobbying body by the TLC.

During these years of dispute and decline within the order, O’Donoghue remained active in both the TTLC and the TLC. Indeed, it is estimated that he moved nearly half of the motions introduced by delegates of the TTLC in the years between 1883 and 1902. Recognizing the importance of training workers, he served on the board of Toronto Technical School from 1891 to 1901. At the same time he remained at the centre of many disputes in Toronto, including the ongoing fight against the street-railway monopoly. In the battle for public ownership, O’Donoghue fell out in 1891 with his old ally Phillips Thompson, whose Labor Advocate represented the interests of progressive labour reform and denounced O’Donoghue and “his small following of rabid Grit factionists.” The street railway and the related labour question of running cars on Sunday led O’Donoghue to become active in the Lord’s Day Alliance in the 1890s; he served on its executive from 1895 until his death. O’Donoghue had expanded his connection with the Reform party in the 1880s and was rewarded with a patronage position in the Ontario Bureau of Industries, a statistical agency formed in 1882 under Archibald Blue* to gather data on labour, industry, and agriculture. Initially he worked voluntarily or on a part-time basis as an investigator, but in 1885 he was made a clerk in the bureau. Following the passage of the Trade Disputes Act of 1894 he also became registrar of conciliation and arbitration boards. The legislation proved ineffective, however, and few boards were ever appointed.

In May 1900 O’Donoghue was made Canada’s first fair-wage officer. Posted with the federal Department of Public Works, he was soon transferred to the newly formed Department of Labour. In this job he had responsibility for establishing schedules of wages for various areas of the country, investigating complaints of non-compliance, and answering enquiries concerning the regulation instituted in March which guaranteed that on all government contracts and subcontracts workers would receive “wages as are generally accepted as current in each trade for competent workmen in the district where the work is carried out.”

O’Donoghue appears to have worked out of Toronto, for his family still resided there in 1901. Although his wife had died in 1895, he had all eight children at home, with the youngest five in school. The family economy was augmented by the earnings of eldest son John George, a court-worker and law student, and eldest daughter Mollie, a music teacher. O’Donoghue’s father-in-law, no doubt retired from the case, lived with them as well.

While working as a fair-wage officer, O’Donoghue became ill in April 1906 in Ferme, B.C. He died, after a lingering illness, in January 1907 at his eldest son’s home in Toronto. His funeral at St Patrick’s Church was attended by many Liberal party dignitaries, including former labour minister Sir William Mulock* and deputy minister William Lyon Mackenzie King*. The pallbearers, however, were all old trade-union allies, among them former Knights’ leaders Richard Devlin and David A. Carey, Toronto printer and former TTU president Edward M. Meehan, and Montreal labour mp Alphonse Verville*. In his funeral oration Mulock applauded O’Donoghue’s “moderating influence against extreme views” and his belief “that in moderation and fairness a cause was best advanced.” The youthful King, who had got his start in the emerging profession of labour expert through O’Donoghue’s tutelage, termed him the “father of the Canadian labour movement.” The present-day Canadian Labour Congress continues this tradition of recognizing him as a major founder of organized labour in Canada.

O’Donoghue established new paths for Canadian workers, in his success during the 1870s as a union leader and Lib-Lab politician, in his large contributions to labour organization in the 1880s, and in his later career as a bureaucrat in the provincial and federal civil service. Though these paths did not lead to the overthrow of the capitalist system – O’Donoghue opposed socialism when it emerged on the Canadian working-class agenda in the 1890s – they did lead to the recognition of labour as an important component of Canadian society. This recognition, certainly, had been one of his major aims.

Daniel John O’Donoghue is the author of “Canadian labour interests and movements,” in Canada, an encyclopædia (Hopkins), 6: 251–65.

Catholic Univ. (Washington), Dept. of Arch. and mss, John Hayes papers; T. V. Powderly papers. NA, MG 26, A, J; MG 29, A15; D61: 6251–52; D71; RG 31, C1, 1881, 1891, 1901, Toronto. Notre-Dame Cathedral (Ottawa), Reg. of marriages, 1827–1900, 15 Sept. 1870. Catholic Register, 24 Jan. 1907. World (Toronto), 17 Jan. 1907. Armstrong and Nelles, Revenge of the Methodist bicycle company. H. J. Browne, The Catholic Church and the Knights of Labor (Washington, 1949). Christina Burr, “Class and gender in the Toronto printing trades, 1870–1914” (phd thesis, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, St John’s, 1992). Can., Dept. of Labour, Report (Ottawa), 1906–7: 9; Parl., Sessional papers, 1906, no.30: 165. Canada investigates industrialism: the royal commission on the relations of labor and capital, 1889 (abridged), ed. G. [S.] Kealey (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1973). Directory, Toronto, 1881–1900. Eugene Forsey, Trade unions in Canada, 1812–1902 (Toronto, 1982). Doris French, Faith, sweat and politics: the early trade union years ([Toronto], 1962). G. S. Kealey, Toronto workers. G. S. Kealey and Palmer, Dreaming of what might be. Labour Gazette (Ottawa), 7 (1906–7): 915. J. G. O’Donoghue, “Daniel John O’Donoghue: father of the Canadian labor movement,” CCHA Report, 10 (1942–43): 87–96. Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, 1895, no.2: 44; 1896, no.3: 45. Robin, Radical politics and Canadian labour. Trades and Labor Congress of Canada, Proceedings of the Canadian Labor Union congresses, 1873–77, ed. L. E. Wismer ([Ottawa, 1951]). Debi Wells, “‘The hardest lines of the sternest school’: working class Ottawa in the depression of the 1870s” (ma thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1982).

Christina Burr and Gregory S. Kealey, “O’DONOGHUE, DANIEL JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/o_donoghue_daniel_john_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/o_donoghue_daniel_john_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Christina Burr and Gregory S. Kealey |

| Title of Article: | O’DONOGHUE, DANIEL JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |