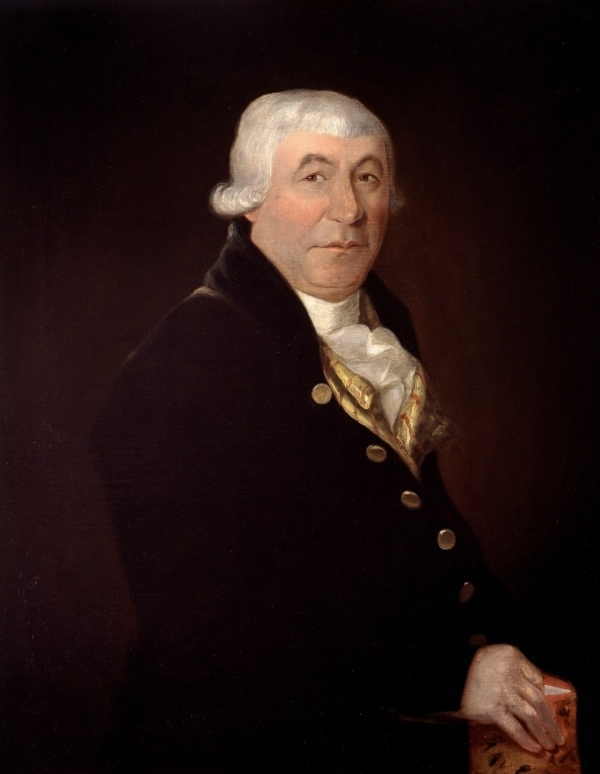

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

McGILL, JAMES, merchant, office holder, politician, landowner, militia officer, and philanthropist; b. 6 Oct. 1744 in Glasgow, Scotland, second child and eldest son of James McGill and Margaret Gibson; d. 19 Dec. 1813 in Montreal, Lower Canada.

The McGill family, probably originating in Ayrshire, had been resident in Glasgow for two generations when James was born. They were metal workers and, from 1715, members of the hammermen’s guild and burgesses of the city. Their fortune rose with Glasgow’s when, following the Union of 1709, the English colonies were opened to Scottish commerce. In 1756, on James’s matriculation into the University of Glasgow, his father was described as “mercator.” The McGills had risen from tradesmen to traders.

When and in what circumstances James McGill emigrated is not known. In 1766 he was in Montreal en route to the pays d’en haut as “the deputy” of the Quebec merchant William Grant (1744–1805). McGill probably wintered on Baie des Puants (Green Bay, Lake Michigan), for in June and July 1767 he was at Michilimackinac (Mackinaw City, Mich.) supervising the dispatch of canoes. He was at Montreal in 1770, but in 1771–72 he was in the field near Fond-du-Lac (Wis.). Like other traders working the southern hinterland of the Great Lakes, McGill conducted simultaneously a number of enterprises with different partners. As early as 1767 he began trading on his own account, obtaining licences for two canoes and cargoes valued at £400. He also posted bonds totalling £2,400 for four traders, one of whom was Charles-Jean-Baptiste Chaboillez, a veteran in the southwest trade. By 1769 McGill had begun his long association with Isaac Todd; about 1770 he also joined with his brother John McGill. John Askin of Michilimackinac, and later of Detroit (Mich.), was McGill’s agent, or “forwarder,” rather than a partner.

In “constant residence” at Montreal from 1775, McGill adapted his family’s urban tradition to Canada. His suppliers were Brickwood, Pattle and Company of London, whose goods he distributed among traders operating in the Indian country. As a minor member of the Anglo-American merchant community, McGill may have felt it expedient to adopt its political views; once in 1770 and twice in 1774 he signed petitions praying for “a general assembly.” Possibly the omission of his name from a memorial against the Quebec Act suggests an improving status that enabled him to act independently. The occupation of Montreal by the troops of the Continental Congress from November 1775 to May 1776 made him conspicuous; he had been one of the group that had negotiated the city’s surrender [see Richard Montgomery*] . He had no truck with rebels, however, and his house became a loyalist rendezvous. His steadfastness cost him 14 puncheons of rum when his cellars were ransacked. “Unhappy people” was his characterization of the despoilers; “many of our Montrl Rebels,” he added, “[have run] off with the others.”

On 2 Dec. 1776 McGill’s marriage with the widow Charlotte Trottier Desrivières, née Guillimin, was solemnized by the Reverend David Chabrand* Delisle, Montreal’s first regularly appointed Anglican pastor. McGill acquired a family, the two surviving sons of Charlotte’s first marriage. The elder, François-Amable*, would become McGill’s partner and principal heir. The younger, Thomas-Hippolyte, would be provided with a commission in the Royal Americans (60th Foot) and his son, James McGill Trottier Desrivières, would be the object of much solicitude at the end of McGill’s life. McGill was fond of children, and he appears to have been drawn especially to the one that bore his name. The years 1775–76 were decisive in McGill’s career; marriage brought him into Mrs McGill’s wide family circle and his commercial position was thus stabilized. His political position was unexceptionable. Shortly after his marriage McGill secured the highly desirable Bécancour house between Rue Notre-Dame and Rue Saint-Paul near the Château Ramezay. It had been the property of Thomas Walker*, one of the chiefs of “our Montrl Rebels.”

In 1776 McGill received his first public appointment, as justice of the peace. It was renewed periodically, and he was thus brought into the administration of Montreal, a function of the justices until 1833. In all, McGill held ten appointments, of which four were of significance: he served in 1788 and 1789 as a member of a commission of inquiry into Lord Amherst*’s claims to the Jesuit estates (educational endowments being considered by many as an alternative use for proceeds from these lands); participated in 1798 with Thomas Blackwood* in the French royalist colony at Windham, Upper Canada; supervised from 1802 the demolition of the old walls of Montreal and the elaboration of plans (entirely abortive) for urban renewal and beautification; and from 1800 oversaw the Lachine turnpike, the first modern road west of the city.

McGill’s business also prospered. In 1775, in association with Todd, Benjamin* and Joseph Frobisher, and Maurice-Régis Blondeau, he sent 12 canoes to Grand Portage (near Grand Portage, Minn.), a shipment that “appears to mark the beginning of large-scale trade to the Northwest . . . and of the Northwest Company,” according to the historian Harold Adams Innis*. Three years later McGill himself was at Grand Portage, probably the farthest point west he reached. With the adoption of the 16-share organization in 1779, McGill and Todd were among the largest shareholders in the NWC. Yet shortly afterwards the McGill group dropped out. Nevertheless, McGill himself continued to post bonds for traders going to the northwest. Todd and McGill retired to “the Ohio Country,” the arc lying south of the Great Lakes. McGill noted about 1785 that this region supplied £100,000 of the total of £180,000 to be derived from the trade in all the territory between the mouth of the Ohio . . . [and] Lake Arabaska [Athabasca].”

The warehouses on Rue Saint-Paul were the centre of the McGill empire. Furs from Detroit and Michilimackinac were exported to Great Britain. Some went by devious ways to New York and John Jacob Astor. The suppliers of furs, the Indians, were carefully cultivated, silver jewellery being bought for them in Montreal. Imported from the West Indies were tobacco, sugar, molasses, and rum; from Britain, metalware, textiles, and powder and shot. Transportation presented problems; the continuation after 1783 of a ban on private shipping on the Great Lakes, begun as a war measure in 1777, provoked McGill to protest. Rudimentary banking was carried on: notes were discounted, foreign currency exchanged, and the pensions of loyalists and French émigrés safeguarded. McGill’s good personal relations with Governor Lord Dorchester [Guy Carleton] were exploited to corner “the flower” supply market of the Great Lakes military posts.

In 1783 the Treaty of Paris, which ceded the Ohio country to the United States, caused McGill and his associates great vexation. In London, Todd, along with other merchants, protested. McGill himself blew hot and cold. In 1785 he threatened to keep his goods at Montreal if “there was the slightest possibility” of a British withdrawal from the ceded territory. At the same time he boasted, “I am clearly of opinion that it must be a very long time before they [the Americans] can even venture on the smallest part of our trade.”

In the threatened area, Detroit was of prime importance. Its geographical advantages were patent and, from 1780 or 1781, it was the home of John Askin, one of McGill’s oldest associates. Askin’s waning success in the fur trade, along with his vast speculation in land, put him heavily in debt to the McGill partners. In brief, they accepted land in lieu of their trade claims and found themselves in legal difficulties after 1796 when Detroit was transferred to the United States. In compensation McGill acquired land on the Canadian side of the Detroit River, along Lake St Clair, and elsewhere in Essex and Kent counties, Upper Canada.

The Detroit land deals, effected between 1797 and 1805, signalled McGill’s entry into systematic land speculation. Earlier acquisitions had been made haphazardly: a farm at L’Assomption, Lower Canada, a water lot at William Henry (Sorel), Montreal properties, a distillery, and probably Burnside, his summer home at the foot of Mount Royal. From 1801 land was secured methodically; that year he acquired 10,000 acres in Hunterstown Township and 32,400 acres in Stanbridge Township, and it was probably in this period that land was secured in Upper Canada near Kingston and York (Toronto).

McGill’s public career approached its apex in the late 1780s. In 1787 he was described as “Militia Mad,” the euphoria being produced by the attainment of his majority; in 1810 he would become the colonel commandant of the 1st Battalion of Montreal’s militia. He began to figure in petitions deploring “the anarchy and confusion” in the administration of civil law. In 1794 he denounced the disturbances in Montreal that attended the embodying of the militia. Two years earlier he had been returned for the riding of Montreal West to the House of Assembly established by the Constitutional Act. His candidacy for the speakership, the highest honour in the assembly, was a tribute to his competence in French and English. In 1792 as well he was appointed to the Executive Council. McGill did not stand for reelection to the assembly in 1796, but he was returned for Montreal West in 1800, and then for Montreal East in 1804.

Around the turn of the century new men entered McGill’s business circle: François-Amable Trottier Desrivières probably in 1792 and Thomas Blackwood eight years later. The newcomers may have prompted new ventures. From 1792 to about 1794 Todd, McGill and Company was a co-partner in the reorganized NWC. In 1796 McGill began to export squared timber. He and Todd were among the planners of a bank in 1807, and McGill himself was active in the Lachine turnpike project. Nor were the old trades neglected. In 1808 McGill joined in the protest against United States interference with the fur traders’ shipping at Niagara (near Youngstown), N.Y.

McGill’s business career epitomized much of the economic development of Lower Canada in the late 18th century. His stake in the fur trade reached its peak in 1782 when he made the largest investment in the colony, some £26,000. By 1790 his investment had fallen to £10,000, the fourth most important that year. Lord Selkirk [Douglas] noted in 1803 that McGill had retired from the fur trade but remained in “the ordinary Colonial trade.” The property on Rue Saint-Paul was sold five years later, and in 1810 the affairs of James and Andrew McGill and Company, which had succeeded Todd, McGill and Company in 1797, were wound up. New interests – “the ordinary Colonial trade,” the manipulation of land, and other activities – had replaced the fur trade. By such means, in a changing economic environment, did James McGill and his fellow merchants assure the metropolitan supremacy of Montreal.

Perhaps warned by deaths in his family circle, of his brothers John and Andrew in 1797 and 1805 and of his sister Isobel, probably in 1808, McGill made his will in January 1811. The major assets were real estate in Lower and Upper Canada and investments in the United Kingdom, the latter not specified as to character or amount. There were also extensive mortgage holdings. The chief beneficiaries were Mrs McGill, her son François-Amable, and James McGill Trottier Desrivières. Old friends were remembered (even the tiresome Askin), the Montreal poor, the Hôtel-Dieu, the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général (Grey Nuns), the Hôpital Général of Quebec, and two Glasgow charities. Alexander Henry* grumbled that McGill’s fortune went “to strangers . . . [and] his wife’s children, Mrs McGill is left comfortable, but young Desrivières will have £60,000.”

McGill also left £10,000 and the Burnside estate of some 46 acres towards the endowment of a college or a university, specifying that the college or one of the colleges of the university should bear the name McGill. The Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning, the agency of the provincial government responsible for schools, was required to open the college or university on the Burnside site before the bequest became operative. It was not till 1821 that a charter was obtained and not till 1829 that teaching began in what is now McGill University. McGill was not a theorist about education; his concern was with “endowments etc,” in the Reverend John Strachan*’s phrase. Strachan certainly encouraged the benefaction. He had joined the McGill circle in 1808 when he married Ann Wood, Andrew McGill’s widow. The actual form of the bequest was doubtless drawn from McGill’s own experience of some 25 years before as a commissioner in the inquiry into the Jesuit estates.

The last 18 months of McGill’s life were clouded by the War of 1812. In February 1812 he warned Governor Prevost of the approaching crisis, probably on the authority of Astor, and on 24 June he communicated the actual declaration. McGill saw no active service but, since he was senior militia officer in Montreal, with the rank of colonel, his staff duties were heavy. He was greatly concerned with the disturbances that attended some of the early militia levies. His civil responsibilities also increased: in 1813 he became temporary president of the Executive Council. He was recommended for membership in the Legislative Council, but death intervened before the appointment became effective.

McGill’s death was sudden; “he had no Idea of going off half an Hour [before] he died” on 19 Dec. 1813. Two days later he was buried in the Protestant cemetery (Dufferin Square), but in 1875 the body was reinterred on the university campus. Contemporaries “reckoned [him] the richest man in Montrl & . . . [one who could] command more cash than anyone”; they savoured “the elevated stations” he attained and admired “the sonorous voice” as he rendered voyageurs’ songs at the convivial gatherings of the Beaver Club. Portraiture presents a less awesome figure. A miniature of about 1790 shows McGill in his prime. The painting by Louis Dulongpré* of only some 15 years later shows the onset of ill health.

James McGill was an 18th-century man. His economics were those of the pre-Adam Smith world. His partnerships, the most complex form of business organization that he knew, were with relatives or close friends. He shared the Enlightenment’s tolerance of confessional divergences; born into the Church of Scotland, he died an Anglican, and half-way through life married a Roman Catholic. He contributed to the support of both the Presbyterian and the Anglican churches at Montreal. In 1805 he became a member of the building committee of Christ Church, which was still in the process of erection when McGill died in 1813. His support of Roman Catholic causes has been noted in connection with his will. McGill felt a strong attachment to place. He left Montreal only on business – there were no sentimental journeys to Scotland. To Montreal his chief benefaction was a university, for which, with characteristic practicality, he gave land and the nucleus of an endowment.

[No complete biography of James McGill exists. The following studies, arranged chronologically, provide the fullest information in print. John William Dawson*, “James McGill and the origin of his university,” New Dominion Monthly (Montreal), March 1870: 37–40, is an amplification of “James McGill and the University of McGill College, Montreal,” which Dawson published in Barnard’s American Journal of Education (Hartford, Conn.), 13 (1863): 188–99. In the 1870 article Dawson incorporated the reminiscences of William Henderson, who, as a young man, had met McGill. The article was reprinted in Dawson’s Educational lectures, addresses, &c. . . . ([Montreal, 1855–95]). Cyrus Macmillan, McGill and its story, 1821–1891 (London and Toronto, 1921), contains a brief biographical sketch. Francis-Joseph Audet* and Édouard Fabre Surveyer included a biography of McGill in their “Les députés au premier Parl. du Bas-Canada,” which appeared serially in La Presse (Montreal) in the late 1920s; the notice on McGill was published on 17 Dec. 1927: 66–67. The biographies were republished by Audet, with valuable notes by Gérard Malchelosse, as Les députés de Montréal. In 1930 Maysie Steel MacSporran submitted her ma thesis, “James McGill: a critical biographical study,” to McGill Univ. The research is very complete, drawing on the collections of the PAC and on the DPL, Burton Hist. Coll. Full use has been made of this thesis. Undated, but probably from the 1960s, is a typescript in the McGill Univ. Arch. by J. M. McGill, “The early history of James McGill, university founder,” based on Glasgow court and municipal records. For what may be called the Scots phase of McGill’s career, J. M. McGill leaves little to add. Finally, Stanley Brice Frost has consecrated an interesting first chapter to McGill in volume one of his McGill University: for the advancement of learning . . . (1v. to date, Montreal, 1980– ). j.i.c.]

ANQ-M, CE1-63, 2 Dec. 1776, 21 Dec. 1813; CN1-363, 2 déc. 1776. ANQ-Q, CN1-16, 27 janv., 17 févr. 1809; CN1-26, 18 déc. 1801; CN1-145, 15 Sept. 1801; CN1-262, 2 oct. 1801. McCord Museum, Beaver Club minute-book. McGill Univ. Arch., James and Andrew McGill journal, 1798–1813; James McGill will. McGill Univ. Libraries, Dept. of Rare Books and Special Coll., ms coll., CH141.S11. NYPL, William Edgar papers (copies at PAC). PAC, MG 11, [CO 42] Q, 30: 202–12; 71: 221; 85: 321–23; 119: 3–5; RG 1, E1, 29–35; RG 4, B28, 115. UTL-TF, ms coll. 31, box 24, notes on the Grant family. “L’Association loyale de Montréal,” ANQ Rapport, 1948–49: 257–73. Bas-Canada, chambre d’Assemblée, Journaux, 1792–96; 1805–8. Doc. relatifs à l’hist. constitutionnelle, 1759–1791 (Shortt et Doughty; 1921), 1: 488–89, 2: 904. Docs. relating to NWC (Wallace). Douglas, Lord Selkirk’s diary (White). “Explorations au Nord-Ouest,” PAC Rapport, 1890: 54–57. [Joseph Hadfield], An Englishman in America, 1785, being the diary of Joseph Hadfield, ed. D. S. Robertson (Toronto, 1933), 112. Invasion du Canada (Verreau), 81–82, 97. John Askin papers (Quaife). [John Strachan], The John Strachan letter book, 1812–1834, ed. G. W. Spragge (Toronto, 1946). Montreal Gazette, 1785–1813. Quebec Gazette, 1777–1813. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Inventaire des cartes et plans de l’île et de la ville de Montréal,” BRH, 20 (1914): 65–66; “Repertoire des engagements pour l’Ouest,” ANQ Rapport, 1942–46. The matriculation albums of the University of Glasgow from 1728 to 1858, comp. W. I. Addison (Glasgow, 1913). Quebec almanac, 1793–1814. Third statistical account of Scotland: Glasgow, ed. James Cunniston and J. B. Gilfillan (Glasgow, 1958). L.-P. Audet, Histoire de l’enseignement au Québec (2v., Montréal et Toronto, 1971). R.-G. Boulianne, “The Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning: the correspondence, 1820–1829, a historical and analytical study” (phd thesis, McGill Univ., 1970). Caron, La colonisation de la prov. de Quebec, 2. I. C. C. Graham, Colonists from Scotland: emigration to North America, 1707–1783 (Ithaca, N.Y., 1956; repr. Port Washington, N.Y., and London, 1972). Henry Hamilton, An economic history of Scotland in the eighteenth century (Oxford, Eng., 1963). L. P. Kellogg, The British régime in Wisconsin and the northwest (Madison, Wis., 1935). Miquelon, “Baby family,” 188–89, 191–92, 194–95. Ouellet, Hist. économique. K. W. Porter, John Jacob Astor, business man (2v., Cambridge, Mass., 1931; repr., New York, 1966). Rumilly, La Compagnie du Nord-Ouest. J. H. Smith, Our struggle for the fourteenth colony: Canada and the American revolution (2v., New York, 1907). L. J. Burpee, “The Beaver Club,” CHA Report, 1924: 73. Ivanhoë Caron, “The colonization of Canada under the British dominion, 1800–1815,” Que., Bureau of Statistics, Statistical year-book (Quebec), 7 (1920): 461–535. Julian Gwyn, “The impact of British military spending on the colonial American money markets, 1760–1783,” CHA Hist. papers, 1980: 91–92. M. G. Jackson, “The beginning of British trade at Michilimakinac,” Minn. Hist. (St Paul), 11 (1930): 259–64. Charles Lart, “Fur trade returns, 1767,” CHR, 3 (1922): 351–58. W. D. Lighthall, “The newly-discovered ‘James and Andrew McGill journal, 1797,’” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., 29 (1935), sect.ii: 43–50. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Quelques maisons du vieux Montréal,” Cahiers des Dix, 10 (1945): 239–41. T. R. Millman, “David Chabrand Delisle, 1730–1794,” Montreal Churchman (Granby, Que.), 29 (1941), no.2: 14–16. Ouellet, “Dualité économique et changement technologique,” SH, 9: 286, 291, 293. Ramsay Traquair, “Montreal and the Indian silver trade,” CHR, 19 (1938): 1–8.

J. I. Cooper, “McGILL, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcgill_james_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcgill_james_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. I. Cooper |

| Title of Article: | McGILL, JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1983 |

| Year of revision: | 1983 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |