Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

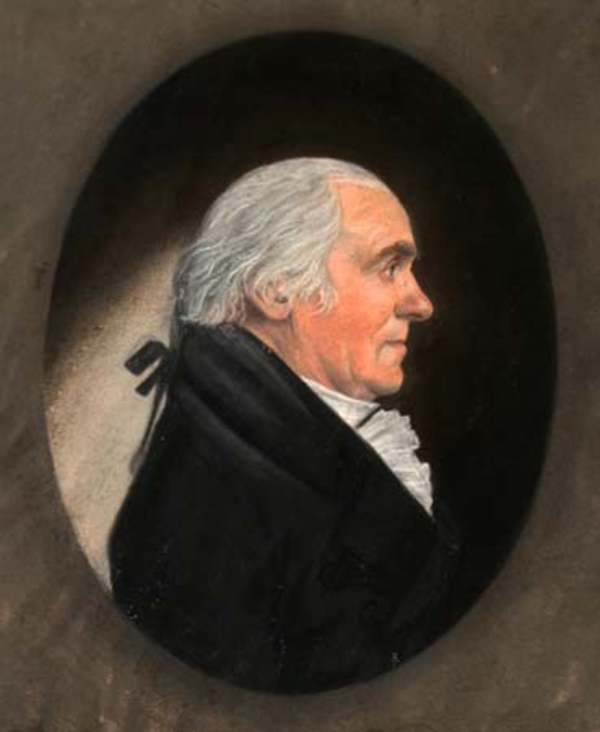

DULONGPRÉ, LOUIS, musician, teacher, stage manager, painter, businessman, and militia officer; b. probably 16 April 1759 in Paris, son of Louis Dulongpré, a merchant, and Marie-Jeanne Duguay; m. 5 Feb. 1787 Marguerite Campeau in Montreal, and they had 13 children, 4 of whom reached adulthood; d. 26 April 1843 in Saint-Hyacinthe, Lower Canada.

There are two versions of Louis Dulongpré’s arrival in North America. According to his obituary in La Minerve, he came with the squadron escorting the troops sent under the Comte de Rochambeau to help the American colonies during the War of Independence, and then out of love for liberty went into the army. But according to Louis-Édouard Bois* in Notice sur M. Jos O. Leprohon, Dulongpré was with the squadron of French vice-admiral Jean-Baptiste-Charles d’Estaing which, after failing to engage the British fleet off Newport, R.I., sailed for the West Indies. There, it is said, he sought a job that suited him, to no avail. Following his return to the American colonies, Dulongpré, who may have been in a musical band of the colonial regulars, reputedly wanted a transfer to Rochambeau’s troops, but the hostilities came to an end. This detailed version is probably the more accurate one, since Joseph-Onésime Leprohon was the son of Jean-Philippe Leprohon, a brother-in-law and neighbour of Dulongpré. Bois also wrote a historical note about Dulongpré’s relative Jean Raimbault.

After he was demobilized Dulongpré visited the former colonies, probably with the idea of settling there. At Albany, N.Y., he met some Canadian merchants who urged him to come to the province of Quebec. He was in Montreal on 30 May and 21 Dec. 1785 when he became godfather to the daughters of the artisans Pierre and Jean-Louis Foureur, dit Champagne.

Dulongpré appeared to Montrealers as a tall, handsome, courteous, and affable figure, elegantly dressed in the style of the ancien régime, with glittering buckles on his shoes and his hair powdered. A man of great urbanity, he was popular with everyone and got along famously with musicians and artists. Those well acquainted with him said he was an accomplished musician who played several stringed and wind instruments. He gave harpsichord and dancing lessons. During the period 1787–92 he regularly advertised his dancing and music school for boys and girls in the Montreal Gazette, and in February 1791 he announced “a Boarding School for Young Ladies, in which they will be taught Reading Writing and Arithmetic, the French and English Languages, Musick, Dancing, Drawing and Needle Work.”

Together with Jean-Guillaume De Lisle*, Pierre-Amable De Bonne*, Joseph Quesnel*, Jacques-Clément Herse, Joseph-François Perrault, and François Rolland, Dulongpré founded the Théâtre de Société in Montreal in November 1789. As manager he undertook to fit out the stage and hall as well as to look after the administrative details, all for £60. He had made his arrangements months before and had rented a large house on Rue Saint-Paul.

In its initial season, from December 1789 to February 1790, the Théâtre de Société put on six plays, among them Colas et Colinette, ou le Bailli dupé, a comic opera by Quesnel. One of the evenings included a ballet and short plays set to choral music for which it seems plausible that Dulongpré and his pupils were responsible. Before the season opened, however, on 22 November the curé of Notre-Dame in Montreal, François-Xavier Latour-Dézery, had denounced theatrical performances from the pulpit, adding that absolution would be refused those who attended. His angry outburst prompted vehement protests and a lively controversy in the Montreal Gazette in which even people from Quebec were involved. As a result, the second season was brief and the members of the company restricted the audience “to a very small number of persons of high birth or noble blood”; they were then accused of favouring the élite and being uninterested in educating the young.

Since Dulongpré was not getting an adequate income from his schools, he changed careers and took up painting. Encouraged by his friends and by the success of painter François Malepart* de Beaucourt, who had been established in Montreal since 1792, Dulongpré decided to go to the United States to complete his training. He stayed from June 1793 till March 1794, living mainly in Baltimore, Md.

Upon his return Dulongpré put an advertisement in the Quebec Gazette stating that he had “lately arrived from the Colonies, where he has improved in the Art of Drawing under the best Academicians” and announcing that he would “paint in Miniature and in Crayons, Pastels.” It is astonishing that in less than one year Dulongpré had mastered his new profession and reached the degree of perfection that characterized his best productions. In addition to his natural gifts he must have possessed a solid artistic base, since he had already painted stage sets. It is not beyond the bounds of possibility that before going to the United States he had taken lessons from Beaucourt. Beaucourt, moreover, had just returned from a stay there and had been able to recommend good teachers.

Dulongpré had few competitors in Montreal other than Beaucourt, who died in 1794, John Ramage*, an excellent miniaturist of Irish descent who died in 1802, and possibly Louis-Chrétien de Heer*. William Berczy* did not take up painting seriously until some 10 years later. At Quebec the only artist who counted was François Baillairgé*.

Dulongpré was successful because he had extensive connections. Over a quarter of a century he painted more than 3,000 portraits – an average of about ten a month – a sizeable number even taking into account the copies attributable to his son Louis and his apprentice Joseph Morant. In his diary William Dunlap, a contemporary American art historian, mentioned that in 1820 Dulongpré would not do portraits and instead was painting historical pictures for Catholic churches at $100 apiece. It is certain, however, that Dulongpré continued to do portraits after this date and that he had become interested in religious art before then.

In fact, upon his return Dulongpré had painted a number of religious pictures for parish churches and convents, and he continued this work throughout his career, with the result that some 200 such items can be attributed to him. He occasionally did gilding and architectural work. He also restored paintings, touching up, for example, several canvassers from the collection sent to Lower Canada by Philippe-Jean-Louis Desjardins*. In 1809 his plan for decorating the vault of the church of Notre-Dame in Montreal was chosen by the fabrique over that of Sulpician Antoine-Alexis Molin.

As a good citizen Dulongpré took an interest in public matters. From 1791 he was a member of the Agriculture Society in the district of Montreal. A few years later he took charge of one of the keys to the fire station on Rue Notre-Dame, a great responsibility at a period when the entire population lived in dread of fires. He dabbled a little in politics and turned out a hundred or so innocuous political caricatures.

Dulongpré also joined the militia. At the outbreak of the War of 1812 he was a captain in the 5th Select Embodied Militia Battalion. He and his men replaced the regular troops in the garrisons of Montreal, Chambly, and Les Cèdres. Promoted a major in September 1813, he took part in the battle of Plattsburgh the following year. On 11 April 1814 he was transferred to the 3rd Select Embodied Militia Battalion. He retired on 30 Aug. 1828 with the rank of lieutenant-colonel as a reward for his loyal services.

For years Dulongpré looked after the affairs of his wife’s family. The estate her father left included at least two properties in the developing Montreal suburbs and a two-storey stone house on Rue Bonsecours. Divided into lots, the properties were rented or sold, with the result that Dulongpré spent a great deal of time in notarial offices, especially as he himself moved a score of times and frequently had to get leases or loans.

Dulongpré owned a huge lot at the corner of Rue Notre-Dame and Rue Saint-Jean-Baptiste with a one-storey stone house. He set out to put a second storey on the house and to build another of similar height next to it. He supervised every detail. The contracts he signed in 1807 with two of the best craftsmen of the period, mason François-Xavier Daveluy, dit Larose, and carpenter François Valade, contained specifications that left nothing to their discretion. Dulongpré lived in his new house for several months, and then in 1808 sold the two buildings for three times as much as they had cost him. In 1816 he had extensive changes made to his old farmhouse in the faubourg Saint-Louis.

In 1812 Dulongpré opened a factory on Rue Notre-Dame for making oiled floor-cloths “as well printed as those imported from Europe . . . at prices as low as those at which they can be imported into the province.” It produced pieces of various sizes: in strips for entrance halls and stairs, and in dimensions suitable for “church sanctuaries . . . with patterns appropriate for the premises.” A complete assortment was available through a Quebec merchant, but Dulongpré’s product apparently could not rival the Bristol one.

In 1832 the Dulongprés left Montreal to be closer to their great friends the Papineaus and Dessaulles, and they took lodgings in Saint-Hyacinthe. At that time they supported themselves mainly through the sale of their real estate in Montreal, the music lessons he gave, and his wife’s modest rentes constituées (secured annuities). An unexpected piece of good fortune, however, soon came their way. Under the terms of a legislative measure to allocate land to veterans of the War of 1812, which was brought forward in the House of Assembly in 1819 but not implemented until 1835, Dulongpré received 1,000 acres in Tring Township.

He invested the major part of his fortune in the Maison Canadienne de Commerce, probably because he heard its praises sung in the Papineau circle. This joint stock company, which had been founded in 1832, proposed to establish a huge warehouse holding all sorts of goods for small merchants, and possibly to finance exports. The moment was ill chosen. A series of poor crops, a slump in the sale of lumber, political events in Lower Canada and abroad: from 1837 everything conduced to the failure of the company.

Mme Dulongpré had to sell her annuities in 1839; she died on 19 July 1840. Dulongpré was deeply affected by the loss of his spouse. A wife without peer for a man who was charming but unconcerned about the future, she was remarkably beautiful, to judge by one of Dulongpré’s best works, Les saisons, which depicts her with her three daughters. As he often used her face in his religious paintings, people would say jokingly that “she had her portrait in all the churches.”

Louis Dulongpré went to live with his daughters in the United States, but he was not happy there, knowing no one, and returned to Saint-Hyacinthe. At the end of 1841 he was living in the home of a Frenchman who had just opened a fine hotel but who took a job in Montreal as a cook a year later. Becoming seriously ill, Dulongpré was taken into the seigneurial manor-house of Saint-Hyacinthe by the wife of Jean Dessaulles*, Marie-Rosalie Papineau, three days before his death.

ANQ-M, CE1-51, 11 janv. 1768, 10 déc. 1779, 5 févr. 1787, 22 nov. 1794, 7 juill. 1796, 21 nov. 1800, 23 mars 1833; CE1-63, 7 févr. 1814, 23 août 1820; CE2-1, 21 juill. 1840, 28 avril 1843; CN1-16, 24 mars, 15 mai 1804; 26 mai 1806; 11 janv., 24 mars, 17 oct. 1807; 11 oct. 1827; CN1-28, 6 oct. 1818; 24, 29 avril, 8 juin, 10–11 août 1819; 5, 7 mai 1821; CN1-74, 19 juill. 1791; 5 juill., 17 août 1811; CN1-110, 5 juin 1822; CN1-121, 28 mai 1789; 29 sept. 1791; 19 sept. 1804; 28 janv., 31 mai 1805; 24, 26 juill., 9 oct. 1811; 5 août 1815; 21 mai 1817; 7 août 1819; CN1-126, 31 déc. 1816; CN1-128, 30 sept. 1796; 29 sept. 1797; 3 avril, 3 août 1798; 28 avril 1802; CN1-134, 22 janv., 24 févr., 2 mars, 29 avril, 16 juin 1816; 22 mai, 22 oct. 1818; 21 juin, 29 sept. 1819; 5, 7 mai 1821; 1er oct. 1822; 18 juin 1824; 30 janv. 1832; 31 mai 1835; CN1-158, 3 févr. 1787; CN1-184, 22 oct. 1805, 14 août 1806, 30 avril 1808; CN1-187, 6 sept. 1832, 11 oct. 1833; CN1-243, 1er oct. 1807; 1er févr., 13 nov. 1809; 19 déc. 1810; 7 févr. 1814; CN1-255, 14 mars 1800; CN1-290, 17 août 1784; CN1-295, 23 août 1803; 11, 15 mai, 28 juill. 1804; 27 janv. 1811; CN1-313, 23 juill. 1796; 28 juill., 23 sept. 1808; CN1-383, 23 févr. 1817. AP, Notre-Dame de Montréal, Boîte 13, chemise 15; Livre de comptes, 1806–18; Plan de décoration de l’église, 27 nov. 1809. AUM, P 58, C2/299; U, Charlotte Berczy to William Berczy, 1 Sept. 1808; William Berczy to Charlotte Berczy, 18, 22 Aug. 1808; Louis Dulongpré à Étienne Guy, 3 juill. 1812; Louis Dulongpré à Hugues Heney, 5 juill. 1828; Jacques Viger à William Berczy, 12 déc. 1811. Bibliothèque nationale du Québec (Montréal), Fonds Édouard Fabre Surveyer, Dulongpré et sa famille. McCord Museum, M21411. PAC, MG 24, B46, 3. La Minerve, 8 mai 1843. Montreal Gazette, 28 Oct. 1787; 20 Oct. 1788; 30 Sept. 1790; 24 Feb., 27 Oct. 1791; 27 Sept. 1792; 4 May 1812; 7 Aug. 1814; 10 June 1816; 14 April, 9, 16 June 1819; 21 May 1825; 8 Sept. 1828. Montreal Herald, 25 Jan. 1816, 1 Feb. 1817. Quebec Gazette, 10 April 1794, 23 April 1812, 3 June 1818, 25 March 1819. [F.-M.] Bibaud, Dict. hist. Canada, an encyclopædia of the country: the Canadian dominion considered in its historic relations, its natural resources, its material progress, and its national development, ed. J. C. Hopkins (6v. and 1v. index, Toronto; 1898–1900), 4: 355. Caron, “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Hubert et de Mgr Bailly de Messein,” ANQ Rapport, 1930–31: 223. Louis Carrier, Catalogue of the Château de Ramezay, museum and portrait gallery (Montreal, 1958). L.-A. Desrosiers, “Correspondance de cinq vicaires généraux avec les évêques de Québec, 1761–1816,” ANQ Rapport, 1947–48: 114. Harper, Early painters and engravers. Langelier, Liste des terrains concédés. Quebec almanac, 1794. Wallace, Macmillan dict. [L.-É. Bois], Notice sur M. Jos O. Leprohon, archiprêtre, directeur du collège de Nicolet . . . (Québec, 1870). C.-P. Choquette, Histoire de la ville de Saint-Hyacinthe (Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué., 1930). [C.-A. Dessaules] e F.-L. Béique, Quatre-vingts ans de souvenirs (Montréal, [1939]). Émile Falardeau, Artistes et artisans du Canada (5 sér., Montréal, 1940–46), 2. Harper, Painting in Canada (1966). Maurault, La paroisse: hist. de Notre-Dame de Montréal. Morisset, Coup d’œil sur les arts; Peintres et tableaux; La peinture traditionnelle. Luc Noppen, Les églises du Québec (1600–1850) (Québec, 1977). Ouellet, Hist. économique, 419, 435, 578. D. [R.] Reid, A concise history of Canadian painting (Toronto, 1973). J.-L. Roy, Édouard-Raymond Fabre, libraire et patriote canadien (1799–1854): contre l’isolement et la sujétion (Montréal, 1974). Sulte, Hist. de la milice. Philéas Gagnon, “Graveurs canadiens,” BRH, 2 (1896): 108–9. J. E. Hare, “Le Théâtre de société à Montréal, 1789–1791,” Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française, Bull. (Ottawa), 16 (1977–78), no.2: 22–26. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Le peintre Dulongpré,” BRH, 26 (1920): 149; “Un théâtre à Montréal en 1789,” BRH, 23 (1917): 191–92. “Le peintre Louis Dulongpré,” BRH, 8 (1902): 119–20, 150–51.

Jules Bazin, “DULONGPRÉ, LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dulongpre_louis_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dulongpre_louis_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jules Bazin |

| Title of Article: | DULONGPRÉ, LOUIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |