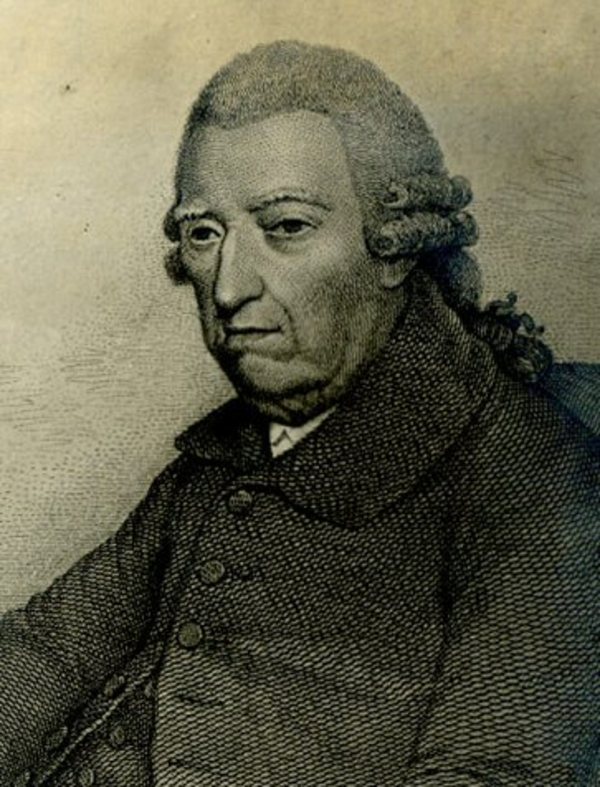

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MASERES, FRANCIS, lawyer, office holder, and author; b. 15 Dec. 1731 in London, son of Peter Abraham Maseres, physician, and Magdalene du Pratt du Clareau; d. unmarried, and was buried 19 May 1824 in Reigate, England.

Francis Maseres excelled in law and mathematics as a student at Clare College, Cambridge, where he received a ba in 1752 and an ma three years later. Giving promise of a distinguished career in law, he was called to the bar in 1758, the year of his first publication, A dissertation on the use of the negative sign in algebra. . . . He proved unsuccessful in establishing a law practice, however, in part, it would seem, from a greater concern that justice – as he saw it – be done in a case than that his client win. Despite his mediocre record as a practising advocate, his reputation for integrity, his exceptional knowledge of the law, and his fluency in French (even if it was the French of the reign of Louis XIV) gave credible backing to his request to friends and acquaintances in 1766 that they secure for him the position of attorney general of Quebec, left vacant by the dismissal of George Suckling*. Among his friends were William Hey*, who had just been appointed Quebec’s new chief justice, and Fowler Walker, London agent for the merchants in the colony. It was perhaps on the advice of Walker that Maseres was recommended by Charles Yorke, attorney general in the Whig administration of Lord Rockingham. In any case, his undoubted qualities marked his appointment, dated 4 March 1766, as one of the happier products of the patronage system.

Maseres immediately set to work studying every available document concerning the province of Quebec and confèrred on several occasions with Hey and Guy Carleton*, the newly appointed lieutenant governor. The three were in substantial agreement on legal and constitutional matters, and Maseres was directed to prepare a pamphlet for circulation among important ministers. In it he seized particularly upon two related questions: the inadequacy of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 as a basis for law in the province of Quebec and the necessity for an act of the British parliament to define the laws, especially those concerning the methods by which revenue might be raised and the position of Roman Catholics in the province. The terms under which a house of assembly might be called (a major bone of contention in the colony between the merchants and Governor James Murray*) needed clarification, but Maseres indicated that he did not consider it expedient to call an assembly for some years.

Maseres sailed for Quebec on 23 June 1766. He found the St Lawrence River “noble” and the country “more beautiful than England itself.” Quebec, however, was “very dirty, partly through the mischief done by the siege . . . and partly from the supineness and indolence of the French inhabitants which make them leave everything in a poor shabby condition.” He observed that the British and Canadian inhabitants “agree together tolerably well and speak well of each other,” but that the British were divided by great animosity [see George Allsopp*].

Maseres himself incurred the wrath of many British merchants soon after taking the oath of office on 26 Sept. 1766, when, in his first important case as attorney general, he argued that customs duties on rum were legal in the province. He cited precedents from the French régime and declared his belief that the British crown had assumed all the powers formerly exercised by the French king. This argument failed to convince a jury composed chiefly of British merchants. In March 1767, in another case, the jury chose to disregard his appeal to them and declared not guilty one of six men charged with assaulting the merchant Thomas Walker*; the result discouraged Maseres from trying the other five. A little more than a year after taking office Maseres again found himself in a controversy with many in the British merchant community for having affirmed that the English bankruptcy laws were in force in the colony; his views appeared in the Quebec Gazette in December 1767 and drew down on him a bitter, anonymous denunciation in the same newspaper, which he ascribed to George Suckling and Thomas Aylwin*, a Quebec merchant.

In large part Maseres’s problems stemmed from the unpopularity of government positions that it was his task to defend. But his own inflexibility and weakness in judging character were clear contributing factors. He seized upon any evidence supporting his views and, for all his training in the law, showed a remarkable tendency to believe those who told him what he wanted to hear. In the Walker case, Maseres continued to reiterate his faith in a crown witness long after others believed the witness’s testimony to be false, and he praised Walker’s conduct in the face of widespread public disapprobation of the merchant. The frequent appearance before the courts of “the violent gentlemen of the army” disgusted Maseres, and he blamed their conduct on laxity in the administration of Governor Murray, whom he described as “a madman of parts.”

Maseres’s weakness in judging character was most evident in religious matters. Coming from a Huguenot family, he was eager to see Protestantism promoted in the colony. He advocated measures intended to favour conversion of the Canadians from Roman Catholicism, without overt persecution or proselytism, through the encouragement of priests prepared to espouse Protestantism and through a gradual weakening of the finances of the Catholic Church in the colony and of the authority of its bishop, Jean-Olivier Briand*. Consequently, he was always willing to hear and to repeat criticism of Briand, and for a long time he assumed that the Huguenot Pierre Du Calvet* and Du Calvet’s later associate, the ex-Jesuit Pierre-Joseph-Antoine Roubaud*, represented a general opinion in the colony. Almost alone, he was convinced of the worthiness of Leger-Jean-Baptiste-Noël Veyssière*, a former Recollet who wished to obtain an Anglican living, and of Veyssière’s ability to persuade Canadian priests and laymen to follow his example in converting to Protestantism. Carleton took a different view, as did Maseres’s friend and confidant, the Reverend John Brooke*, who, for supporting the governor, was accused by Maseres of “a low and foolish piece of flattery” and thenceforth deprived by the incensed attorney general of any further contact with him. Before long Carleton would note Maseres’s “want of knowledge of the World, and his having conversed more with books than with Men.”

Despite a growing concern over the limitations of Maseres’s judgement and his religious views, the governor retained faith in his attorney general’s ability to produce an effective plan for the administration of justice in the colony. After it became known at Quebec in March 1768 that the British government required the governor and council, with tire assistance of the chief justice and the attorney general, to report on the judicial system and to present a draft ordinance covering proposed changes, Maseres was given the task of drawing up the report. It has often been claimed that until then Maseres had been ready to revive the entire body of French civil law, as Carleton desired, but that in the process of preparing his report he deviated from this course. However, his private correspondence before this time indicates frequent shifts in emphasis, as he grappled with the difficulties inherent in any proposal for the administration of justice. It was likely his realization of the complexity of French civil law and of its application in a society ethnically mixed and commercially tied to Britain rather than any sudden change of heart that produced the “Draught of an Intended Report.”

Maseres devoted more than one-third of his document to an examination of the contradictory nature and sometimes dubious legality of each provision made for the government of Quebec since the capitulation. The wording of this section has given rise to speculation concerning Maseres’s change of attitude during 1768, yet on close examination it becomes apparent that many of his statements are conditional; Maseres seems to have been determined to leave the decision to the British government, but to awake its ministers to an appreciation of past errors without overtly criticizing them or their predecessors in office.

After this lengthy introduction, Maseres presented his only concrete recommendations. He advocated essentially a return to the practice of the French régime in the administration of justice, a plan with which the governor would agree. However, the basic problem was not the machinery of justice but the uncertainty as to which law was in force, and here Maseres refused to commit himself. Instead, he outlined four possible solutions, stating the difficulties involved in each and leaving the reader to weigh the evidence. The proposals were: creating a code specifying every law, whatever its origin, that should prevail in Quebec; reviving the entire French legal system with a few English laws introduced by ordinance; introducing English law except for a few general exceptions in which French law should be followed; adapting the third plan so as to specify precisely what former customs were to be the law of the province. Maseres objected to both the second and the third plan because they would involve constant reference to French precedents and “keep up in the minds of the Canadians that reverence for the law and lawyers of Paris, and that consequential opinion of the happiness of being subject to the French government.” He warned that the apparently easiest methods of dealing with the problem would be attended by the worst results.

Maseres seems to have considered that a code of laws combining English and French usages was the ideal solution, but the difficulties in preparing such a code had become obvious to him. When François-Joseph Cugnet* had prepared a digest of French laws, Maseres and Hey had taken four hours to master the first five pages, even with the author present to explain them. Yet Maseres concluded, “When I did understand it, I thought the several propositions neatly and accurately expressed.” Presumably other lawyers could also be led to understand the digest, but a more serious problem could not be so easily resolved. Other Canadians disputed Cugnet’s version of French law as it had operated in New France, and any effort to secure agreement on a code would have precipitated the reference to French precedents that Maseres sought to avoid.

Maseres presented his report to the governor in February 1769 and had it promptly rejected. Maurice Morgann*, who had arrived at Quebec the previous summer to convey the opinions of colonial, officials back to London, denounced Maseres’s work as “extreamly defective and improper” and declared that there was not a useful idea in it. This statement, obviously far too sweeping, may have reflected the governor’s impatience with his attorney general’s effort. Any administrator was likely to condemn a report that failed to provide a clear line of direction or to present proposals that could be immediately translated into the required ordinance. Hey and Morgann were then enjoined by Carleton to prepare material, and in September 1769 the governor dispatched to London over his signature a report that owed something to a variety of documents, including, it would seem, earlier work by Maseres on the character of the pre-conquest legal system. Both Hey and Maseres sent written dissents from Carleton’s report. In his comments Maseres expressed his views less equivocally. He recommended the formulation of a legal code and stated the opinion, contrary to the one he seemed to hold as recently as a few months before, that English law had been introduced into the province as a result of the conquest. But even in this most extreme statement of his views, Maseres made it clear that he considered it essential to retain, at least for the time being, all French laws pertaining to “the tenure, inheritance, dower, alienation, and incumbrance of landed property, and to the distribution of the effects of persons who died intestate.”

The disagreement between Carleton and Maseres over the latter’s report crowned the attorney general’s increasing disillusionment with the colonial experience. Professionally, he had lost all his major cases in court, judicial reforms that he had projected were blocked by the grand juries or in council, and his carefully considered report on the laws and administration of justice had been rejected out of hand. He had not even the feeling of having made a significant contribution to improvement, which would, he remarked, “balance the disagreeable circumstances of living in a sort of banishment in this frozen kingdom of the Northwind.” Within a year of his arrival at Quebec he had wanted to return to England. The colony lacked natural and social graces. “There are no downs to ride upon, no pleasant green lanes, no parks or forests or gentleman’s seats to go and see, or gentlemen to visit at them,” he complained. The land was covered either by commonplace farms or impenetrable woods. Intellectual life was non-existent, Catholicism ubiquitous. In the autumn of 1769 Carleton granted him a one-year leave of absence, but relations between the two men had so deteriorated that it was understood Maseres would not come back.

After his return to England, Maseres published several works dealing with Quebec. The first, Draught of an act of parliament for settling the laws of the province of Quebec, published in August 1772, proposed among other things the adoption for Quebec of a civil code compiled by Cugnet, Joseph-André Mathurin Jacrau*, and Colomban-Sébastien Pressart* and known in the colony as the “Extrait des Mes sieurs.” Cugnet violently opposed several aspects of Maseres’s plan, and, offended by his attacks, Maseres published in August 1773 Mémoire â la défense d’un plan d’acte de parlement pour l’établissement des loix de la province de Québec, in which he refuted them systematically. Maseres had modified slightly an earlier version of his Draught so as to meet some of the objections of Cugnet and Michel Chartier* de Lotbinière, but he could not agree to the admission of Roman Catholics into the government of Quebec. His contention that he had Canadian support for his plan was based on an optimistic reading of a highly selective correspondence from persons who remained anonymous. In 1774 he was called as a witness before the committee of the House of Commons considering the Quebec Bill and, as spokesman in Britain for the colonial merchants, he unsuccessfully opposed many of Carleton’s judicial and constitutional proposals. He made it clear to the merchants, however, that he remained unwilling to press for either the elective assembly they desired or the immediate uprooting of all French laws and customs. He urged them to support, for the time being at least, an enlarged legislative council, more independent of the governor, but still without the power to levy taxes. There seems little doubt that, from this time on, Maseres was able to exercise a certain restraint upon the demands of the British inhabitants.

Once the Quebec Bill became law, Maseres was the natural conduit through which petitions from British merchants in the colony for its abolition or amendment were transmitted to Westminster. For them he expressed concern over the absence of habeas corpus and trial by jury, and in 1775 he published An account of the proceedings of the British, and other Protestant inhabitants, of the province of Quebeck, in North America, in order to obtain an house of assembly in that province. He followed it in 1776 with Additional papers concerning the province of Quebeck, which included recommendations for effecting a reconciliation between Britain and her rebellious American colonies, consisting largely of concessions to the Americans’ grievances. Among his proposals were repeal of the Quebec Act and its replacement by a new act confirming the boundaries set by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and establishing in Quebec English law with specific exceptions, and, if possible, a Protestant house of assembly, elected by Protestants and Catholics. These proposals were repeated in The Canadian freeholder, published in three volumes between 1777 and 1779. In early 1784, along with Jean-Baptiste-Amable Adhémar*, Jean De Lisle*, Pierre Du Calvet, and William Dummer Powell, he declared his support for a petition brought to London by Powell in which the British merchants of the colony called for a house of assembly. He also published the petition that year.

Governor Frederick Haldimand* fulminated against the influence Maseres wielded in London, not only in favour of the colonial merchants’ reform movement, but also in favour of Du Calvet, who was there to obtain compensation for imprisonment by Haldimand on suspicion of treason. So strongly did Maseres believe in this case that he financed Du Calvet’s lawsuits against Haldimand and the publication of two of Du Calvet’s pamphlets. In addition, with the chief justice of Quebec, Peter Livius*, he is said to have drafted The case of Peter Du Calvet, which he published in March 1784. Du Calvet’s secretary, Pierre-Joseph-Antoine Roubaud, stated that in one meeting “Mr. Maseres explained himself in a tone of vehemence and agitation, which surprised me in an Englishman. There was none of the national phlegm; it was Gascon vivacity and quickness; in a word the most heated enthusiasm.”

However much Haldimand protested Maseres’s activities, he seemed prepared to accept him as chief justice at Quebec. If such a possibility existed it was removed when Maseres’s old adversary Carleton, now Lord Dorchester, secured appointment to Quebec as governor-in-chief; with him came the new chief justice, William Smith*. In London Maseres continued to interest himself in the colony. It may have been he who in 1788 published A review of the government and grievances of the province of Quebec, although the author was more probably Adam Lymburner*; if the publication was Maseres’s, he acknowledged in it more than he had previously done the influence of patriotic, or national, sentiment and social thought. The following year James Monk, who had been dismissed as attorney general of the colony for a virulent attack on its judges and judicial system, drew heavily on the Review in a pamphlet condemning the arbitrary nature of the administration of justice and of government in the colony. When some of the judges published a rebuttal in 1790, Maseres himself replied the same year in Answer to an introduction to the observations made by the judges of the Court of Common Pleas. It was his last new publication on Quebec affairs; probably the partial victory of the merchants represented by the Constitutional Act of 1791 removed the necessity for an agent in legal and constitutional matters. In 1809, however, he reprinted a number of his earlier publications in Occasional essays on various subjects, chiefly political and historical.

After his return to England Maseres had taken up rooms in the Inner Temple (where he had been admitted in 1750); in 1774 he had been made a bencher, in 1781 a reader, and the following year treasurer. He had become a fellow of the Royal Society in 1771 and cursitor baron of the exchequer in 1773 (a sinecure he held until his death). From 1780 to 1822 he was senior judge of the sheriff’s court in London. A man of wealth who could pursue his special interests, he published widely on mathematics and optics, as well as on legal, religious, and historical questions, and financed the publication of many works by authors he deemed worthy of assistance. Much of his time each year was spent in chambers, and the remainder he passed at his country home in Reigate, where he died in May 1824.

Rather short physically, Maseres had always dressed in a fashion “uniformly plain and neat” and he retained to the last “the three-cornered hat, tye-wig, and ruffles” of the reign of George II. He was known, the Gentleman’s Magazine remarked in 1824, for “the cheerfulness of his disposition, his inflexible integrity, the equanimity of his temper, [and] his sincere piety.” Although he made no great mark on the legal profession and even joked of his lack of success as a lawyer before going to Quebec, few knew English law as well, “and in questions of great moment,” noted the Gentleman’s Magazine, “the members of both houses have frequently availed themselves of his judgement and superior information.” Jeremy Bentham called him the most honest lawyer England ever knew.

Out of the controversies in which he engaged, Maseres acquired a reputation for anti-Catholic prejudice (presumably part of his Huguenot heritage) that has established him as an enemy of the Canadians and tended to enshrine his opponents as heroes. Carleton’s declaration – “I very soon discovered his strong Antipathy to the Canadians, for no Reason, that I know of, except their being Roman Catholics” – has pursued Maseres down the centuries, but it does little to explain the changes in his views of a society in which Catholicism was a constant; and there is ample evidence that Maseres’s concepts of law and society were no mere “rationalization of prejudice.” According to a contemporary, he held “the most liberal views of toleration on religious opinions,” yet the same writer affirmed that “the Baron was an Anti-Catholic.” In a sense both these apparently contradictory statements are correct. It was Maseres’s belief in freedom that led him to distrust the political power of the Roman Catholic Church, which he identified with illiberalism. While he would not exclude a deist or an atheist from public office, he would block accession to a Roman Catholic on the ground that it was a tenet of Catholicism not to tolerate heresy, and he felt that “who will not tolerate others ought not to be allowed to possess civil employments, which may gradually give them an influence in the state.” But his refusal to countenance a place for Catholics in government did not prevent him from aiding them against their oppressors during the French revolution; a contemporary observed that “his house was open to the refugees from France, where were to be seen archbishops and bishops . . . driven from their homes by the atheistical bigotry of the time.” At bottom, given Maseres’s perception of Catholicism, his refusal to accept Catholic influence in government was in keeping with his whig political views and insistence on political liberty.

The historian William Stewart Wallace* found in Maseres’s agency in London for the British colonial merchants before and during the American revolution his most significant contribution to Canadian history, for his “championship of the cause of the merchants of Quebec and Montreal was a safeguard and guarantee of the loyalty of a large part of them.” It may be argued that his role was more negative and perhaps more important. At the same time as he distrusted Roman Catholicism in politics, he seems to have underrated the influence of religious faith on human actions and thus the tenacity with which the Canadians would consider their religion to be part of their identity. His views encouraged British merchants to maintain in their program of political and legal reforms anti-Catholic measures that at once intensified opposition to it in some Canadian circles and prevented Canadians otherwise disposed to support the program from joining in a common drive to achieve it. He thus contributed to delaying the entire constitutional and legal development of the colony. He looked for principles in politics that would approach the certainty he perceived in mathematics, but a search for universal values that transcended religion and nationality has earned him repeated denunciations by, in the words of historian Hilda Marion Neatby*, “nationalist romantics of the nineteenth century and nationalist zealots of the twentieth.”

Francis Maseres was a prolific writer on mathematics and on legal and political subjects. His most important works relating to Quebec are: Considerations on the expediency of procuring an act of parliament for the settlement of the province of Quebec (London, 1766); The trial of Daniel Disney, esq. . . . (Quebec, 1767); Considerations on the expediency of admitting representatives from the American colonies into the British House of Commons (London, 1770); Draught of an act of parliament for settling the laws of the province of Quebec ([London, 1772]); A draught of an act of parliament for tolerating the Roman Catholick religion in the province of Quebec, and for encouraging and introducing the Protestant religion into the said province, and for vesting the lands belonging to certain religious houses in the said province in the crown of the kingdom for the support of the civil government of the said province and for other purposes ([London, 1772]); Things necessary to be settled in the province of Quebec, either by the king’s proclamation or order in council, or by act of parliament ([London, 1772]); Mémoire à la défense d’un plan d’acte de parlement pour l’établissement des loix de la province de Québec . . . (Londres, 1773); Réponse aux observations faites par Mr. François Joseph Cugnet, secrétaire du gouverneur & Conseil de la province de Québec pour la langue françoise, sur le plan d’acte de parlement pour l’établissement des lois de la ditte province . . . ([Londres], 1773); An account of the proceedings of the British, and other Protestant inhabitants, of the province of Quebeck, in North America, in order to obtain an house of assembly in that province (London, 1775); Additional papers concerning the province of Quebeck: being an appendix to the book entitled, “An account of the proceedings of the British, and other Protestant inhabitants, of the province of Quebeck, in North America, [in] order to obtain a house of assembly in that province” (London, 1776); The Canadian freeholder: in two dialogues between an Englishman and a Frenchman, settled in Canada, shewing the sentiments of the bulk of the freeholders of Canada concerning the late Quebeck-Act; with some remarks on the Boston-Charter Act; and an attempt to shew the great expediency of immediately repealing both those acts of parliament, and of making some other useful regulations and concessions to his majesty’s American subjects, as a ground for a reconciliation with the united colonies in America (3v., London, 1777–79); Observations and reflections, on an act passed in the year, 1774, for the settlement of the province of Quebec, intended to have been then printed for the use of the electors of Great Britain, but now first published (London, 1782); The case and claim of the American loyalists impartially stated and considered (London, 1783); The case of Peter Du Calvet, esq., of Montreal in the province of Quebeck; containing (amongst other things worth notice,) an account of the long and severe imprisonment he suffered in the said province . . . (London, 1784) [written in collaboration with Pierre Du Calvet and Peter Livius]; Questions sur lesquelles on souhaite de sçavoir les réponses de monsieur Adhémar et de monsieur De Lisle et d’autres habitants de la province de Québec (Londres, 1784); A review of the government and grievances of the province of Quebec, since the conquest of it by the British arms . . . (London, 1788); Answer to an introduction to the observations made by the judges of the Court of Common Pleas, for the district of Quebec, upon the oral and written testimony adduced upon the investigation, into the past administration of justice, ordered in consequence of an address of the Legislative Council, with remarks on the laws and government of Quebec (London, 1790); Occasional essays on various subjects, chiefly political and historical . . . (London, 1809). In addition, Maseres compiled A collection of several commissions, and other public instruments, proceeding from his majesty’s royal authority, and other papers, relating to the state of the province in Quebec in North America, since the conquest of it by the British arms in 1760 (London, 1772; repr. [East Ardsley, Eng., and New York], 1966). His correspondence, with an introduction, notes, and appendices by William Stewart Wallace, was published as The Maseres letters, 1766–1768 (Toronto, 1919).

BL, Add. mss 35915 (copies at PAC). Lambeth Palace Library (London), Fulham papers, 1: ff.120–60. PRO, CO 42/20; 42/26–29. Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1759–91 (Shortt and Doughty; 1918). Gentleman’s Magazine, January–June 1824: 569–73. Reports on the laws of Quebec, 1767–1770, ed. W. P. M. Kennedy and Gustave Lanctot (Ottawa, 1931). William Smith, The diary and selected papers of Chief Justice William Smith, 1784–1793, ed. L. F. S. Upton (2v., Toronto, 1963–65), 1: 264; 2: 65, 67, 69, 77, 90, 145. DNB. A. L. Burt, The old province of Quebec (2v., Toronto, 1968), 1. John Mappin, “The political thought of Francis Maseres, attorney general of Canada, 1766–69” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1968). Neatby, Quebec.

Elizabeth Arthur, “MASERES, FRANCIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maseres_francis_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maseres_francis_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Elizabeth Arthur |

| Title of Article: | MASERES, FRANCIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |