Source: Link

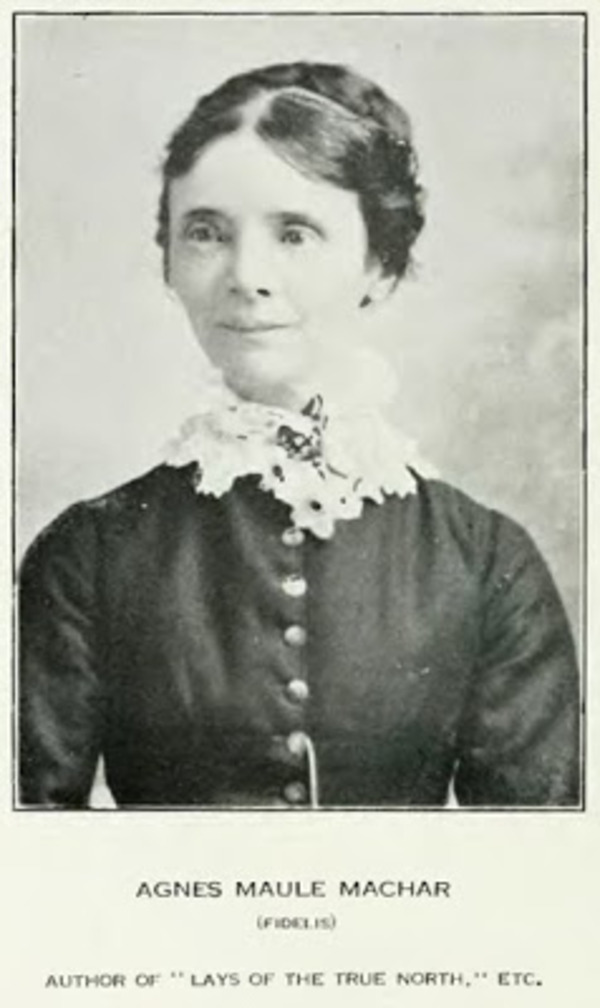

MACHAR, AGNES MAULE, author and social reformer; b. 23 Jan. 1837 in Kingston, Upper Canada, daughter of John Machar* and Margaret Sim; d. there unmarried 24 Jan. 1927.

John Machar, a Church of Scotland clergyman, left Scotland for Kingston in 1827 to become pastor of St Andrew’s Church. He helped found Queen’s College and was its principal from 1846 to 1853. His wife, herself the daughter of a Scottish clergyman, had joined him following their marriage in Montreal in 1832. Their first child lived only briefly; Agnes was born in 1837 and her brother, John Maule, four years later. Except for a year in a Montreal boarding school, she was educated by her father, who possessed an excellent library. Before she was ten he was instructing her in Latin and Greek; French, German, and Italian followed. Agnes throve on this regime, her precociousness in the study complemented by a love of the outdoors. After her father’s death in 1863, she remained with her mother, a leader in good works who died in 1883. Agnes then moved in with her married brother, and she stayed on in his house on Sydenham Street following his passing in 1899.

Despite her residence in a small colonial city, Machar had the benefits of a rich social and intellectual milieu. Along with the sources of stimulation available to her as a youth in the manse, there were those that had come from her parents’ acquaintances, among them politicians John A. Macdonald* and Richard John Cartwright*; Queen’s professor George Romanes, whose son George John would achieve fame in England as an associate of Charles Darwin; and cleric Joseph Antisell Allen and his son Charles Grant Blairfindie, who would make his mark as a novelist and popularizer of Darwinian science, and whose sister Caroline Elizabeth became Agnes’s sister-in-law in 1879. Later, as a well-known author, Agnes developed her own circle and, especially at Ferncliff, her summer home in Gananoque near the Thousand Islands, she hosted international figures who shared her interest in literature, religion, and science. On her travels she came to know some of the era’s famous writers, including the one she most admired, Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier. Among prominent Presbyterians she seems to have been closest to Daniel James Macdonnell*, an intimate of her family from his days at Queen’s, and George Monro Grant*, its principal from 1878 to 1902. A key figure in Canada’s small community of literary and artistic women, and something of a mentor to its younger members, she decried the neglect and premature death in 1887 of Isabella Valancy Crawford*; on happier occasions, she welcomed Emily Pauline Johnson* and other women writers to Ferncliff, which Grant Allen publicized so well in Longman’s Magazine (London).

Agnes Machar had the time, wit, and vigour to turn her opportunities to good account in a stream of publications. These began anonymously in childhood; her first book, a memorial to a janitor at Queen’s, appeared in 1859. The last three decades of the century were her most prolific. Her career could be said to have been launched by her prize-winning novel Katie Johnstone’s cross: a Canadian tale (Toronto, 1870). Often writing under the pseudonym Fidelis, she subsequently produced a memorial to her father, at least eight novels, and numerous poems and essays. She also wrote or collaborated on six works of popular history, in addition to other publications. Her poetry appeared in American, British, and Canadian periodicals, a selection being published as Lays of the “True North,” and other Canadian poems (London and Toronto, 1899). Patriotic and imperial themes informed much of her verse, but the natural beauty surrounding Ferncliff was her joy and most frequent inspiration. Generations of Canadian schoolchildren encountered her verse in their readers. This exposure, and the fact that her poems and novels won prizes and, like her histories, were often reissued, testifies to the degree to which her work struck a chord with contemporaries. Many of her essays can still be read with profit. The range of her interests can best be sampled from the pieces printed in the dominion’s leading intellectual journal, the Canadian Monthly and National Review/Rose-Belford’s Canadian Monthly and National Review, between 1872 and 1882 and in the Toronto Week in 1883–96.

Written for Sunday school libraries, Katie Johnstone’s cross had introduced a classic Machar figure to Canadian literature: the girl or young woman whose faith, moral standards, and good works inspire errant males to turn from wrongdoing or recover their Christian belief. Shifting later in the decade to adult readers in a series of essays in the Canadian Monthly, Machar rose to the challenge of defending the Christian faith against the onslaughts of scientific rationalism and higher criticism. She did not insist on unchanging views of creation and the Bible; rather, she asked orthodox Christians and those on the brink of scepticism to accept evolutionary theory and critical readings of the Bible as the means to a new and fuller understanding of God’s work. She may not have won many over, but she did win respect. In 1876 secularist and skilled controversialist William Dawson LeSueur* declared that, of those who had questioned his arguments in the Canadian Monthly on the efficacy of prayer, Machar had given the most satisfactory response. Although she regarded Christianity as the “fullest revelation” of God and personally remained within the Presbyterian fold, her theological liberalism did allow for a sympathetic interest in other religions, particularly Buddhism.

Machar’s defence of Christianity also sought to make it socially relevant, especially in terms of what a Christian society owed to the poor in the new industrial age. Her thinking here showed considerable development. In an essay in 1879 she recommended measures to assist the urban poor, including Prohibition, state-funded work programs, and refuges. She worried, however, that if the churches became almoners to the largely unchurched poor they might encourage hypocrisy and pauperization. In the years that followed, when economic depression was accentuating poverty, her experience and wide reading, which included American Social Gospel literature, In darkest England and the way out by the Salvation Army’s William Booth, and the 1889 Report of the royal commission on the relations of labour and capital, led her to a broader perspective. She now maintained that the real hypocrisy lay in churches that preached to the poor about their souls while disregarding their bodily needs. Privileged Christians needed to recognize that the poor had a right to work, justice, and the means to rise above subsistence.

Machar delivered this message most fully (if not as forcefully as in some of her articles) in Roland Graeme: knight . . . (Montreal, 1892). In this well-received novel, orthodox Christians applaud a mill owner who gives $5,000 to the church even as they ignore the miserable dwellings in which he houses his workers and the grim factory where they toil for wages he threatens to reduce. Challenging this villain and a complacent clergyman is a crusading journalist, Roland, who espouses “Christian socialism.” He joins the Knights of Labor and stands by the workers when they strike. Inspired by a minister who is the clergyman’s opposite and by Nora, a female paradigm of applied Christianity, he recovers his faith and develops a new attitude to the urban poor. Cautious in its ending and unoriginal in its message, the book was nonetheless a pioneering Social Gospel novel, even somewhat radical in having as its hero a member of a controversial labour organization. Roland was perhaps based in part on Machar’s barrister brother, who sympathized with the Knights and the reformist views of Henry George.

Though the elderly poor did not figure significantly in Roland Graeme, they became a source of particular concern for Machar. In a paper presented to the National Council of Women of Canada in 1895, she recommended that homes be established for them, by the state if necessary, and that the homes be “as little regarded as charity for the veteran in the industrial army, as is the pension of the old soldier.” Moreover, Prohibitionist though she was – three of her essays on temperance had appeared in the Canadian Monthly in 1877 – she wanted the housing to be sufficiently homelike to allow for, it seemed, the occasional drink. In the end, it was elderly women whom she would assist directly, by leaving a bequest to establish the Agnes Maule Machar Home “for old ladies past earning their own livelihood.” Opened in Kingston by the Local Council of Women in 1930, it still functions.

Like many other English Canadians, Machar was a proud nationalist and imperialist. She took little interest in the mechanics of nation-building, instead promoting a vision with high moral purpose, purged of sordid party politics and “racial” tension. This vision was evident as early as 1875 in “Lost and won: a story of Canadian life,” a novel serialized in the Canadian Monthly and so apropos that Machar and her publisher took care to assert that no reference was being made to contemporary political events, then still tainted by the Pacific Scandal. In 1879 she used a Dominion Day poem to suggest that, as leaders of a young nation where the “waxen mould” was still soft, Canada’s politicians had the opportunity to set a moral example. Few of them took note, but parliamentary expert John George Bourinot* was so enamoured of this lofty idea 16 years later that he used a stanza of the poem to conclude his How Canada is governed (Toronto). Reviewers applauded.

Machar’s interpretation of Canada’s history was deployed to this same visionary end, and to promote patriotism. Though she was by no means unique among English/Protestant writers in her celebration of French Canada’s past, her efforts are noteworthy because they were directed towards children as well as adults, were made through poetry and fiction as well as “factual” narratives, and were intended to mitigate French-English tensions. When her Stories of New France, written in two parts with Thomas Guthrie Marquis* penning the second, was published in 1890, in the wake of Quebec’s controversial Jesuits’ Estates Act, reviewers who recognized the book’s moderating purpose praised its timeliness. As history, Machar’s part is a light, unexceptional retelling of the stories of Samuel de Champlain*, Jacques Cartier*, Huronia, and the like. Occasionally she left the relatively safe terrain of history to address contemporary issues directly, as in her poem “Quebec to Ontario, a plea for the life of Riel, September 1885” and in letters advocating clemency for Louis Riel* in the Canada Presbyterian (Toronto). In taking this position she swam against a strong current, as evidenced by letters of chastisement in the latter. In her last literary effort at crisis management, Young soldier hearts of France: a wreath of immortelles (Toronto, 1919), produced in her eighties, she edited and translated the letters of gallant French soldiers who had died in World War I. Given the state of relations between French-speaking Canada and the rest of the dominion, her gesture was sadly naive but wonderfully consistent.

Machar took a similar visionary approach to the British empire and Canada’s place within it. The empire had flourished because it fulfilled a “Divine purpose.” Admittedly for some it was a source of material aggrandisement or chauvinistic pride (shallow young Englishmen are stock figures in Machar’s fiction). But it was here that Canada could play a role, by calling Britain back to its ancient ideals and function as the moral jewel in the imperial crown. Formal ties such as a Canadian presence in an imperial parliament did not interest Machar – spiritual and cultural links that required no institutional structures were her concern. Until 1913, when she published Stories of the British empire . . . (London and Toronto), verse was her main vehicle for promoting such links. Lays of the ‘True North’ of 1899 began with the poem that had won her the Week’s prize for the best verse commemorating Queen Victoria’s jubilee in 1887. The poem touched on what Machar saw as the most important imperial task, advancing the spread of Christianity. This spiritual aspect allowed her to work without national constraint for one of her abiding goals, closer ties between Britain, Canada, and the United States, and the undermining of what the Week called “Yankeephobia.” Her aim led her to positions that were decidedly unusual for a nationalist/imperialist: yes to reciprocity with the United States in 1891 but no to an imperial trade zollverein two years later, and a resounding no to Canada’s stand in the Bering Sea dispute, where Machar’s environmental concerns confirmed her belief that the Americans were right in trying to halt pelagic sealing [see Clarence Nelson Cox*].

As a feminist, Machar was chiefly concerned with education and paid work. She challenged prevailing arguments that higher education would unsex women, maintaining instead that it would allow them to develop their God-given talents, make them better Christians, wives, and mothers, and, if marriage did not fall “naturally to their lot,” assist them to earn “an honourable competence.” Like most of her contemporaries, she assumed that married women should ideally be full-time homemakers, yet she recognized that it was often necessary for poor women to work. In essays and in a resolution presented to the National Council of Women in 1896, she called for legislation to improve the conditions of work for women and children in shops and factories. Her advocacy of shorter hours for female factory workers was challenged by Carrie Matilda Derick*, a lecturer at McGill University and a prominent council member, who maintained that such legislation was inconsistent with women’s calls for equality of opportunity with men. Although Machar seems not to have pressed the council to lobby for equal pay for women, she did make adequate remuneration an issue in her writing.

Machar’s organizational ties reflected her interests. In the 1880s she was treasurer of the Kingston wing of the Presbyterian Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society and in the 1890s she sat on the executives of the Local Council of Women and the national body. She served as president of the Kingston Humane Society and as secretary of the local Young Women’s Christian Association, and was a founder of the Canadian Audubon Society. During the first decade of the new century she was a founding member of the Canadian Women’s Press Club, a vice-president of the Canadian Society of Authors, and a member of the Kingston branch of the Women’s Art Association of Canada. Her intellectual gifts and literary accomplishments would certainly have qualified her for membership in such organizations as the Royal Society of Canada, but her gender kept her out. And she seems not to have belonged to the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, despite her support for Prohibition.

Though widely travelled, Machar never lived extravagantly, and she appears to have carefully managed her income from writing. When she died in 1927, she left an estate worth about $52,800, most of it in mortgages. To her “faithful friend and helper” Matilda Speers she bequeathed an annuity; Ferncliff she gave to two other close friends, T. G. Marquis and Lawson Powers Chambers, a Queen’s graduate and professor of philosophy at Washington University in St Louis, Mo.

An exemplar of the theological liberalism and socially oriented Christianity present in late Victorian Canada, and of the national and imperial zeal that preoccupied many of its writers, Machar was nonetheless unusual in the range of issues she addressed and in some of the apparently paradoxical positions she adopted. Yet in keeping with her pseudonym, Fidelis, she was remarkably consistent. A century after her heyday, scholars may cringe at her poetic references to the “dusky Hindoo,” the “low-browed savage,” and the “hardy Indian,” all succumbing willingly to the “hope and progress” brought by Victoria’s Christian empire. In the end, however, most of those who have studied her career probably share the fond assessment of Alfred Edward Prince of Queen’s, in 1934, that Agnes Machar had lived a large-hearted life and died “rich in character, rich in achievement.”

[No collection of Agnes Maule Machar’s papers has been located. Some of her correspondence is available in the Louisa Murray fonds in York Univ. Libraries, Arch. and Special Coll. (Toronto); the Helena Coleman papers, file 152, in Victoria Univ. Library, Special Coll. (Toronto); and the George Monro Grant papers in NA, MG 29, D38. Her estate file is in AO, RG 22-159, no.3867. Information on her background can be found in Memorials of the life and ministry of the Rev. John Machar, D.D., late minister of St. Andrew’s Church, Kingston (Toronto, 1873), compiled by members of the family and edited by Agnes, and in John Machar’s biog. file at the UCC-C.

Machar’s first book, published anonymously, was Faithful unto death, a memorial of John Anderson, late janitor of Queen’s College, Kingston, C.W. (Kingston, [Ont.], 1859). Her novels include Katie Johnstone’s cross: a Canadian tale (Toronto, 1870); Lucy Raymond, or, the children’s watchword (Toronto, [1871?]); For king and country: a story of 1812 (Toronto, 1874; originally serialized in the Canadian Monthly and National Rev., Toronto); “Lost and won” (serialized in the Canadian Monthly in 1875 but not subsequently published, although journalist and poet Thomas O’Hagan regarded it as one of her two best novels: see O’Hagan, infra); Marjorie’s Canadian winter, a story of the northern lights (Boston, 1892; repr. Toronto, 1906); Roland Graeme: knight (reprinted in Toronto in 1906 and again in 1996; the modern reprint, including an introduction by Carole Gerson, was issued as part of the Early Canadian women writers series); Down the river to the sea (New York, 1894); and The heir of Fairmount Grange (London and Toronto, [1895]). The quest of the fatal river (Toronto, 1904) is attributed to Machar in several sources including Wallace, Macmillan dict., and the Canadian annual rev., 1904: xiv, but researchers have been unable to locate any copies. A memorial entitled Mère Marie-Rose, fondatrice de la Congrégation des SS. Noms de Jésus et de Marie au Canada (Montréal, 1895), which is attributed to Machar in some libraries because its author also used the pseudonym Fidelis, was in fact written by Jules-Henri Prétot.

Besides Lays of the “True North” (a second enlarged edition of which was issued at London and Toronto in 1902), there are several more specialized collections of Machar’s poems, including The Thousand Islands (Toronto, 1935), assembled after her death by Thomas Guthrie Marquis and published in the Ryerson poetry chap-book series. In addition to those discussed in the text, Machar’s historical works include The story of old Kingston (Toronto, 1908). Her work as a historian is discussed in D. M. Hallman, “Cultivating a love of Canada: Agnes Maule Machar, 1837–1927,” in Creating historical memory: English Canadian women and the work of history, ed. Alison Prentice and Beverley Boutilier (Vancouver, 1997), 25–50.

More extensive lists of Machar’s publications can be found in Nancy Miller Chenier, “Agnes Maule Machar: her life, her social concerns, and a preliminary bibliography of her writing” (ma research essay, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1977), and in D. M. Hallman, “Religion and gender in the writing and work of Agnes Maule Machar” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1994). Her contributions to the Canadian Monthly and its successor, Rose-Belford’s Canadian Monthly and National Rev., are listed in the Index compiled by Marilyn G. Flitton (Toronto, 1976).

Among the sketches of Machar written during or just after her lifetime, and useful for identifying her Canadian and international circle of friends, are A. E. Wetherald, “Some Canadian literary women – II: Fidelis,” Week (Toronto), 5 April 1888: 300–1; Thomas O’Hagan, “Some Canadian women writers,” Week, 25 Sept. 1896: 1050–53; L. A. Guild, “Canadian celebrities, no.73: Agnes Maule Machar (Fidelis),” Canadian Magazine (Toronto), 27 (May–October 1906): 499–501; F. L. MacCallum, “Agnes Maule Machar,” Canadian Magazine, 62 (November 1923–April 1924): 354–56; Robert William Cumberland’s tributes in the Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston), 34 (1926–27): 331–39, and Willisons Monthly (Toronto), 3 (1927–28): 34–37; and the entry by Alfred Edward Prince in Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1.

Recent secondary sources on Machar by historians include M[ary] Vipond, “Blessed are the peacemakers: the labour question in Canadian Social Gospel fiction,” Journal of Canadian Studies (Peterborough, Ont.), 10 (1975), no.3: 32–43; Ruth Compton Brouwer, “The ‘between-age’ Christianity of Agnes Machar,” CHR, 65 (1984): 347–70, and “Moral nationalism in Victorian Canada: the case of Agnes Machar,” Journal of Canadian Studies, 20 (1985–86), no.1: 90–108; Ramsay Cook, The regenerators: social criticism in late Victorian English Canada (Toronto, 1985); and Constance Backhouse, Petticoats and prejudice: women and law in nineteenth-century Canada ([Toronto], 1991). A study from a literary perspective is Carole Gerson, “Three writers of Victorian Canada,” in Canadian writers and their works, ed. Robert Leckie et al. (24v. in 2 ser., Toronto, 1983–96), fiction ser., 1 (1983): 195–256. r.c.b.]§

Ruth Compton Brouwer, “MACHAR, AGNES MAULE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/machar_agnes_maule_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/machar_agnes_maule_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ruth Compton Brouwer |

| Title of Article: | MACHAR, AGNES MAULE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |