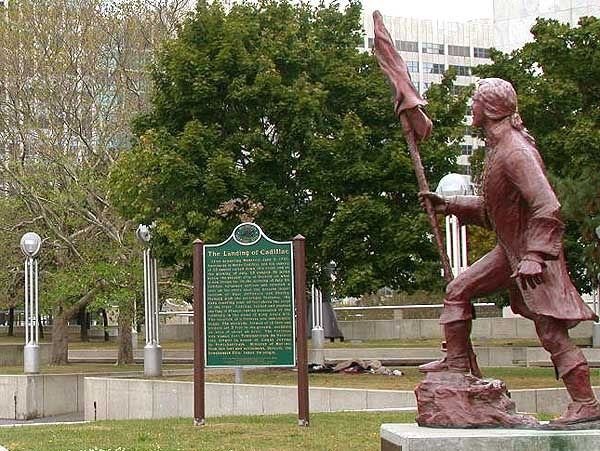

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

LAUMET, dit de Lamothe Cadillac, ANTOINE, seigneur in Acadia, captain in the colonial regular troops, sub-lieutenant in the navy, commandant of Michilimackinac, founder of Detroit, governor of Louisiana, knight of the order of Saint-Louis, governor of Castelsarrasin in France; a turbulent figure in the history of New France, described by Agnes Laut as among the “great early heroes in North American history” and by W. J. Eccles as, “one of the worst scoundrels ever to set foot in New France”; b. at Les Laumets, near Caumont (department of Tarn-et-Garonne), 5 March 1658; d. at Castelsarrasin, 15 Oct. 1730.

Boastful, ingenious, quarrelsome, not too scrupulous about adhering to the truth, Antoine Laumet was a true son of Gascony. He has gone down in history with the impressive noble pedigree he invented for himself, consisting of the title of esquire, a coat of arms, the noble alias of de Lamothe Cadillac, and a father who was counsellor in the prestigious parlement of Toulouse. The truth is quite different. Cadillac’s baptismal certificate, preserved in the parish of Saint-Nicolas-de-la-Grave, shows that his father, Jean Laumet, was a humble provincial magistrate, and his mother, Jeanne Péchagut, of bourgeois stock. Assuming a noble identity was of course a common practice in 17th-century France, but Cadillac may have hoped to gain more by this than merely social prestige. The thorough manner in which he blurred over his real origins, going so far as to alter the name of his mother to Malenfant on his wedding certificate of 25 June 1687, has led several historians to believe that for some reason or other he wished to make it impossible for anyone to inquire about his real identity.

Little is known of Cadillac’s life before he came to Canada. It is clear from his voluminous American correspondence which, although untrustworthy, is invariably witty and well written, that he received a good education. On occasion he even ventured into the field of scholarship with rather startling results. While commanding at Michilimackinac he wrote a report to prove that the western Indians were closely related to the Jews. As for his claim to have held a commission in the French army, it is almost invalidated by the contradictory statements he made about his rank and regiment. In 1690 he told a clerk of the ministry of Marine that he had been an infantry captain; the following year he informed Frontenac [Buade*] that he had held the rank of lieutenant in the Régiment Clairambault; in a memorial of the mid 1720s to the ministry of Marine he had demoted himself to a cadet in the Régiment de Dampierre-Lorraine.

About 1683 Cadillac landed in Acadia as an obscure immigrant and settled in Port-Royal (Annapolis Royal, N.S.). Shortly afterwards he took service under François Guion, a privateer who had stopped there to equip his vessel. While serving under Guion he gained an extensive knowledge of the New England coast which later made him a valuable man in the eyes of the French government. He also had the opportunity to visit Guion’s home at Beauport, near Quebec, where he fell in love with Marie-Thérèse, the daughter of François’ elder brother, Denis. They were married in Quebec on 25 June 1687, and returned to Acadia where Cadillac was granted a seigneury of 25 square miles on the Douaguek River (Union River, Me.).

Cadillac never developed this wilderness tract; fighting with the governor, Des Friches de Meneval, kept him far too busy for that. Cadillac, it seems, had formed a trading partnership with Soulègre, commandant of the Port-Royal garrison, and Mathieu de Goutin, the chief commissary. When Meneval informed Soulègre and de Goutin that as officers they were forbidden to engage in trade, the three partners schemed against him. They sought to alienate the priests from him and, when this failed, tried to turn the people against the priests by urging them not to pay the tithe. Meneval was soon complaining in the strongest terms about the three cronies. “This Cadillac,” he stated in one dispatch, “who is the most uncooperative person in the world, is a scatter-brain who has been driven out of France for who knows what crimes.” A clerk of the ministry of Marine who had occasion to speak with Cadillac shortly afterwards had much the same impression of him: “He was recognized as being very sharp indeed, and quite capable of the practices Mr de Menneval noted.”

In the summer of 1691 Cadillac arrived at Quebec with his family and not a penny to his name. In May of the previous year his Acadia habitation had been destroyed, along with several other houses in the vicinity of Port Royal, by Sir William Phips*. Never had Cadillac’s prospects been bleaker, but they soon began to brighten perceptibly. Although the court had been alerted by Meneval to the type of man he was, it still considered that with his knowledge of the Atlantic seaboard he might render valuable service should an attack be launched against Boston or New York. Frontenac was therefore instructed to grant Cadillac employment in the royal service and to help him in every possible way. The governor, who had taken an instant liking to the glib, boisterous Gascon was only too happy to oblige and made him a lieutenant in the colonial regular troops. In 1692, Cadillac made a reconnaissance trip along the New England coast with Jean-Baptiste Franquelin, the mapmaker, and submitted to the royal government a detailed and accurate report on the geography of the area. In recognition of this service he was promoted to the rank of captain in October 1693. The following year, Frontenac appointed him commandant of Michilimackinac, at the junction of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan.

Michilimackinac was the most important military and trading station held by New France in the western country. To command there at the height of the Iroquois war was a heavy responsibility. Basically the duties of the commandant were threefold: to keep all the western tribes in the French alliance, to make them live in harmony with each other, and to induce them to wage war relentlessly on the Five Nations. It is quite odd that Frontenac and his secretary, Charles de Monseignat, the author of the annual “Relation of the most Remarkable Canadian Occurrences,” should have asserted that Cadillac was acquitting himself very well in this work when the facts they reported proved the exact contrary. Cadillac was unable to prevent the Hurons and Iroquois from exchanging embassies for the purpose of concluding a peace treaty; he was unable to preserve harmony between the various western tribes, much less persuade them to form a large striking force to attack the Iroquois. In 1697, when Cadillac returned to Canada, Monseignat reported that affairs in the Great Lakes region were “extremely confused.”

Cadillac may have been a failure as a commandant but he proved to be very adroit as a fur-trader. When he arrived at Michilimackinac late in 1694, his capital assets consisted only of his captain’s pay of 1,080 livres annually. Three years later he sent to France letters of exchange valued at 27,596 livres 4 sols which represented only a part of his net profits. These gains were realized in two ways: by selling unlimited quantities of brandy to the Indians, a practice which both angered and distressed the Jesuits, Father Carheil and Father Joseph Marest; and by fleecing the coureurs de bois, few of whom dared to complain because they knew that Cadillac was protected by Frontenac. The commissary of the king’s troops, Louis Tantouin de La Touche, best summed up the nature of Cadillac’s tenure as commandant when he stated: “Never has a man amassed so much wealth in so short a time and caused so much talk by the wrongs suffered by the individuals who advance funds to his sort of trading ventures.”

On 21 May 1696, the situation in the west was drastically altered. To reduce the flow of beaver pelts into the colony, a flow which had saturated the French market, Louis XIV issued an edict which abolished the fur-trading licences (congés) and ordered the withdrawal of the garrisons from the principal western posts. This law obliged Cadillac to return to Canada, where he arrived on 29 Aug. 1697, with a large flotilla of canoes bearing nearly 176,000 pounds of beaver pelts. By that date, in order to keep the western tribes under French influence, Louis XIV had issued a second edict which allowed the retention of the posts of Fort Frontenac, Michilimackinac, and Saint-Joseph des Miamis. The ban on trade in the west, however, was not lifted and the governor claimed that this restriction made the reoccupation of the posts unfeasible since it deprived the men of their chief means of subsistence. As for Cadillac, he was not interested in returning to the hinterland if he could not engage in the fur trade. In 1698 he sailed for France to present to the court a new programme for the west which is the master-stroke of his career – the colonization of Detroit.

What Cadillac proposed to establish at Detroit was not a garrisoned post such as the one he had commanded at Michilimackinac but a small colony where a considerable body of Frenchmen would settle and where all the western tribes would regroup. Such a settlement, Cadillac promised, would serve military, economic, cultural, and moral ends. Militarily, it would prevent English expansion in the Great Lakes region and, being located on the doorstep of the Iroquois, would enable the French to send a large army against them at a moment’s notice in case of war. Economically, since the Indians would be far too busy moving to their new home from scattered points in the west to find time for hunting, Detroit would help slow down the beaver trade. Culturally, a large white settlement at the centre of the continent would facilitate the Frenchification of the western tribes. Morally, the exploitation of the Indians by the coureurs de bois which took place in the depths of the wilderness would cease at Detroit where civil and religious personnel would be present to supervise transactions between them.

Pontchartrain, the minister of Marine, was impressed by these arguments, but he prudently decided to refer the whole matter to Louis-Hector de Callière and Jean Bochart de Champigny before making a decision. The reaction of these officials was hardly enthusiastic. The intendant claimed that even if Cadillac did succeed in grouping all the western tribes in one place this would be of no advantage to New France since ancestral rivalries would soon cause them to fly at each other’s throats. Callière feared that the Iroquois might be offended by a settlement built on their hunting grounds and renew their war on Canada. Furthermore, by drawing the western allies close to the Five Nations, Detroit would make it easy for all these Indians to trade together and perhaps eventually to conclude an alliance detrimental to the French. The merchants were also alarmed. Detroit, they realized, commanded one of the main commercial cross-roads of the Great Lakes country and whoever controlled it could rapidly become the master of the whole fur trade. Taken aback by the strength of the opposition, Cadillac, who had returned to Canada in the spring of 1699, hurried back to France in the fall to refute these objections. With his powers of persuasion he was able to overcome Pontchartrain’s hesitations. In the dispatches of 1700, the governor and intendant were told to put the project into execution, unless “insurmountable obstacles” were discovered.

With Alphonse Tonty as his first lieutenant, Cadillac arrived at Detroit with 100 men in the summer of 1701. Two years later Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil became governor of New France and almost immediately the two men were at loggerheads. Personality differences made some friction between them inevitable. A descendant of an old family of the military nobility, formerly a member of the crack Musketeers, the new governor regarded the slick Gascon parvenu with contempt. The root of the quarrel, however, lay in policy, not personalities. By his actions at Detroit soon after his arrival there, Cadillac showed that he wanted to make himself the master of the northwest. In 1704 he was granted the ownership of his post and on a number of occasions afterwards he asked Pontchartrain to make the area under his command into a separate government. Vaudreuil, for much the same reasons as Callière, considered that Cadillac’s experiment was essentially unsound. He favoured a return to the traditional pattern of posts and fur-trading licences into which Detroit, shorn of its pretences of becoming the unique post in the west and the place of residence of all the western tribes, would fit as one of several garrisoned posts. Such a system, however, would also have made it impossible for Cadillac to rise to the position of power to which he aspired. He therefore decided that Vaudreuil was an enemy who had to be destroyed.

His anti-Vaudreuil campaign was cleverly conducted. He began by winning the support of two powerful Canadian notables: Claude de Ramezay, the governor of Montreal, and Ruette d’Auteuil, the attorney general of the Conseil Supérieur, battle-hardened by many years of political infighting with Frontenac. The trio – shades of Acadia! – accused Vaudreuil of persecuting Cadillac and plotting to bring about the downfall of Detroit. Why? Because this new settlement was a challenge to his control of the fur trade. “The great project of the Canadian authorities,” stated Cadillac, “is to establish Michilimackinac on the basis of fur-trading licences and coureurs de bois. This is the great inducement offered by the governor general, and it allows him to be, so to speak, in command of trade.” To hammer the point home, d’Auteuil added that Vaudreuil had experienced “extreme displeasure to see placed in a post that might interfere with his trade a man who was put there by someone other than himself and on whom he could not count for support in his greedy designs.”

Vaudreuil was not endowed with Cadillac’s mental agility, but he invariably struck with force and deadly accuracy once he had assessed a situation. So it was in this case. Cadillac, Ramezay, and d’Auteuil, he claimed, far from being allied by common feelings of concern for the welfare of the colony, simply shared the common ambition of profiting from the Detroit fur trade. Furthermore, their anticipated gains would not materialize through legal trading channels but through contraband. This was the reason why Cadillac was asking that his zone of command become a separate government, since he could then trade with the English, secure in the knowledge that no one could call him to account for his actions. He had won Ramezay to his side by giving him a stake in his settlement; he had completed arrangements with Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville to ship beaver down the Mississippi; he had gone so far as to offer Vaudreuil himself 500 to 600 pistoles annually in return for an agreement not to interfere with his commerce. If he should succeed in his plans, Canada would be ruined irreparably.

Only Pontchartrain could settle this dispute but he hesitated a long time before taking action. Cadillac’s memoirs of 1698 and 1699 had deeply impressed him and for many years afterwards in thinking about Detroit he considered “that one way of retaining possession of North America was to prevent the English and other nations from penetrating inland.” That Vaudreuil, to satisfy his personal ambition, should be plotting to overthrow this important settlement was judged intolerable. In June 1706 the governor was sternly warned to mend his ways or suffer the full consequences of royal displeasure. But even as these words were being written doubts were growing in the minister’s mind about Cadillac’s character and the soundness of his policy. The air of independence assumed by the commandant of Detroit, his extravagant vocabulary, and the wild accusations he hurled at the governor, the intendant, and the Jesuits lent support to the complaints about his insubordination, arrogance, and irresponsibility. Moreover, it was fast becoming evident that his Indian policy was a failure. In 1706 and 1707, in what came to be known as the Le Pesant affair, the Hurons, Ottawas, and Miamis who had settled near Detroit came to blows and almost plunged the west into war. Upon hearing of this development, Pontchartrain finally decided that the time had come to clear the air once and for all. In November 1707 he appointed François Clairambault d’Aigremont to investigate and report on conditions in the west.

D’Aigremont’s report, submitted in November 1708, was a crushing indictment of Cadillac as a profiteer and of his policy as a menace to French control of the interior. It began by pointing out that Detroit was not the highly developed settlement which Cadillac was describing in his dispatches in order to induce the minister to separate it from Canada. Besides the military garrison and a few hundred Indians there were but 62 French settlers and 353 acres of land under cultivation. Over this domain Cadillac exercised a tyrannical rule which had earned him the hatred of white and red man alike. Tradesmen were obliged to pay him large sums of money for the right to ply their craft; a jug of brandy, which cost two to four livres in Canada, sold for 20 at Detroit.

The report also confirmed the governor’s fears about the adverse effect Detroit might have on the French network of Indian alliances. This outpost, for all practical purposes, had become a satellite of New York’s commercial sphere; almost all its fur crop ended up in English hands. As for the Iroquois, they lost no opportunity to trade with the French allies, sometimes allowing them to travel as far as Albany to trade directly with the English, and gradually winning them to their side by these tactics. “This shows,” concluded d’Aigremont, “that the Iroquois have taken advantage of the period since the founding of Detroit to win over our allies in order to have them on their side in case of war, which would certainly be the case.”

It was impossible for Pontchartrain to go on supporting Cadillac after this devastating report, but it was also difficult for the minister to punish him severely. To have done so after upholding him for so long would have been tantamount to admitting his own mistake; rather than share in the discomfiture of his former favourite Pontchartrain preferred to pack him off to Louisiana as governor. François Dauphin de La Forest, who had succeeded Tonty as Cadillac’s first lieutenant, became the commandant of Detroit. The confidential jottings of a clerk of the ministry of Marine explain the reasons for this appointment. La Forest was considered a mediocre officer without enough ability to command a western post. By putting him in charge of Detroit, Pontchartrain hoped to bring about the collapse of this discredited settlement. He would thus rid himself of a troublesome problem without having to take the embarrassing step of reversing his former policy.

Louisiana, of which Cadillac was appointed governor on 5 May 1710, was without a doubt the most dismal colony in the French empire. Founded by Iberville ten years before, it had a total population of 300 to 400 persons, ridden by vice and disease, who eked out a precarious existence on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. The French government, its coffers drained dry by the War of the Spanish Succession, could do little for the development of this territory and was hoping to transfer it to Antoine Crozat, one of the richest men in France. To overcome the financier’s understandable reluctance about such an undertaking, Pontchartrain turned to Cadillac who had gone back to France after leaving Detroit instead of following instructions and proceeding directly to Louisiana. Cadillac presented Crozat with memoirs which spoke of the gulf colony as a land of immense mineral wealth. Like the minister of Marine 12 years before, the millionaire entrepreneur could not keep himself from falling under the amazing Gascon’s spell. In September 1712 a company was formed for the development of Louisiana to which Crozat contributed 600,000 to 700,000 livres and Cadillac his administrative talents. This arrangement, it seems, made Cadillac believe that he would be Crozat’s principal representative in Louisiana; but other officials appointed by the company and the crown deprived him of much of the authority he hoped to wield and also appreciably reduced the possibilities of personal enrichment.

Cadillac landed in Louisiana in June 1713 and he was not impressed by what he saw. The colony, he informed the minister, was a “wretched place” inhabited by “gallows-birds with no respect for religion and addicted to vice.” Prospects of future development, he went on, hinged entirely on the discovery of mines and the establishment of trade relations with Mexico. Cadillac made a serious effort to implement this two-point programme. Soon after his arrival, he sent an overland expedition towards Mexico under the command of Louis Juchereau* de Saint-Denis. Unfortunately, Spain’s policy proscribed trade between her colonies and foreign powers and the expedition completely failed in its purpose. As a prospector, Cadillac was more successful. In 1716 he personally inspected the Illinois country where he located a copper mine.

Meantime, true to his old self, Cadillac was quarrelling furiously with his colleagues in government. Even before landing in Louisiana he had managed to antagonize the colony’s newly appointed financial commissary – the equivalent of the Canadian intendant – Jean-Baptiste Du Bois Duclos. During the voyage across the Atlantic aboard the Baron de La Fauche Cadillac warned Duclos that it would be dangerous to quarrel with him because he had a superior mind. Duclos conceded that Cadillac was a dangerous man, not because of his superior mind, which he judged to be quite mediocre except when his own interests were involved, but because he was “very troubled and very restless” and “the most barefaced liar I had ever seen.” Then, soon after landing in Louisiana, Cadillac began to quarrel with the king’s lieutenant, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne* de Bienville. According to Bienville, the trouble began when he offended Cadillac by refusing to marry his daughter, Marie-Madeleine; thereafter, he complained, he was treated like a corporal. On one occasion the assistant town major paid Bienville a visit to inform him in the governor’s name that he was a “dolt” and a “fop.” Cadillac, unfortunately, did not limit himself to name calling. Out of spite he obstructed Bienville’s work among the Indian tribes and Louisiana’s relations with the native populations sharply deteriorated.

By 1716, Crozat had wearied of Cadillac whom he held responsible for the colony’s stagnation and even suspected of concealing Louisiana’s real wealth in order to profit from it personally. Cadillac, for his part, had wearied of Crozat whom he accused of breach of contract. The decision to recall the governor was taken at the financier’s insistence on 3 March 1716, but it was only in the summer of the following year that Cadillac with his whole family sailed out of Mobile Bay for France. A career of 34 years in the colonies had come to an inglorious end.

On 27 September 1717, less than one month after arriving in France, Cadillac and his eldest son, Antoine, were clapped in the Bastille where they remained until 8 February. The charge against them was that “of having made improper statements against the government of France and of the colonies.” Crozat’s monopoly had recently been transferred to the Compagnie de l’Occident which, to encourage immigration to Louisiana, described the colony as another Eldorado. Cadillac, for his part, regarded Louisiana as “a monstrous confusion” and he protested publicly and loudly against the company’s fanciful description. Lest he jeopardize its entire publicity campaign it was deemed prudent to remove him from circulation for a few months.

Subsequently, however, the ministry of Marine repented the harshness with which it had treated Cadillac. It granted him the cross of the order of Saint-Louis and paid all his salary arrears as governor of Louisiana, even for the period from 1710 to 1712, when he had not yet taken up his position, and for 1718, after he had lost it. Emboldened by these successes, Cadillac next attempted to recover the possession of Detroit, including the exclusive right to the trade of the post, but after studying his petition the council granted him only the ownership of some of the land, buildings, and cattle. Cadillac did not profit from this ruling since he never returned to Detroit nor did he send a deputy there. In 1723, he purchased the governorship of Castelsarrasin, a small town 12 miles from Montauban, carrying an annual salary of 120 livres. He died there on 15 Oct. 1730. His last seven years in France are as obscure as the 25 which preceded his coming to America.

A critical examination of the thousands of pages of archival material relating to Cadillac inevitably leads the historian to the conclusion that he most definitely was not one of the “great early heroes” and probably deserves to be ranked with the “worst scoundrels ever to set foot in New France.” How, then, did the Cadillac myth originate? Perhaps in three ways. First, because the settlement he founded in 1701 grew into one of the principal cities of the United States, it was to be expected that civic-minded Detroiters with a taste for history would seek to make him into a great man. Secondly, Cadillac’s correspondence taken in isolation creates the illusion that he was a devoted, able, and far-seeing servant of the crown who had to struggle unceasingly against the persecutions and petty schemes of less gifted men. Thirdly, Cadillac was anticlerical. His hostility to the Jesuits, his fulminations against what he once termed “an odious, ecclesiastical domination that is quite intolerable” endeared him to English Protestant historians as one of the few persons in the history of New France who dared assert his independence of priestly control and defend the prerogatives of the state against the church. Thus, with the passing of time, an individual who had never been anything but a cunning adventurer in search of personal enrichment came to be regarded as one of the great figures of the French régime in America.

[The bulk of the manuscript material on Cadillac is in the following series: AN, Col., B, 16–42; C11A, 12–43; C11D, 2; C11E, 14, 15; C11G, 1–6; C13A, 2–4; D2C, 47, 49, 51; F³, 2, 7, 8, 9, 10; Marine, B1, 1–55. Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal (Paris), Archives de la Bastille, 10631, 12482. BN, MS, Clairambault 849, 882; NAF 9274, 9279, 9299 (Margry).

Some of these documents have been published by Pierre Margry, Découvertes et établissements des Français, V, but this compilation must be used with circumspection since documents hostile to Cadillac have been either edited or omitted. More satisfactory is “The Cadillac Papers,” edited by C. M. Burton and published in Michigan Pioneer Coll., XXXIII, 36–716; XXXIV, 11–303. A fairly balanced picture of Cadillac will emerge if this compilation is used in conjunction with the correspondence of Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, published in APQ Rapport, 1938–39, 12–179; 1939–40, 355–463; 1942–43, 369–443; 1946–47, 371–460; 1947–48, 137–339.

Readers interested in the evolution of historical opinion on Cadillac should consult the works given below. C. M. Burton, Cadillac’s village (Detroit, 1896); A sketch of the life of Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, the founder of Detroit (Detroit, 1895); and Agnes Laut, Cadillac, knight errant of the wilderness . . . (Indianapolis, 1931) are highly favourable to Cadillac, particularly the last which, although it claims to be based on the sources, reads like a bad historical novel. Between 1944 and 1951 the Jesuit Jean Delanglez published a series of scholarly articles on Cadillac: “Cadillac’s early years in America,” Mid-America, XXVI (1944), 3–39; “Antoine Laumet, alias Cadillac, commandant at Michilimackinac,” XXVII (1945), 108–32, 188–216, 232–56; “The genesis and building of Detroit,” XXX (1948), 75–104; “Cadillac at Detroit,” XXX (1948), 152–76; “Cadillac, proprietor of Detroit,” XXXII (1950), 155–88, 226–58; “Cadillac’s last years,” XXXIII (1951), 3–42. This series of articles utterly destroys the Cadillac myth. Eccles, Frontenac; Giraud, Histoire de la Louisiane française; and Y. F. Zoltvany, “New France and the west,” deal with Cadillac at Michilimackinac, Detroit, and in Louisiana, and are all equally critical of him.

E. Forestié, Lamothe-Cadillac, fondateur de la ville de Détroit (Montauban, 1907), is the only serious inquiry into Cadillac’s early years in France. y.f.z.]

Yves F. Zoltvany, “LAUMET, dit de Lamothe Cadillac, ANTOINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/laumet_antoine_2E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/laumet_antoine_2E.html |

| Author of Article: | Yves F. Zoltvany |

| Title of Article: | LAUMET, dit de Lamothe Cadillac, ANTOINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1969 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |