Source: Link

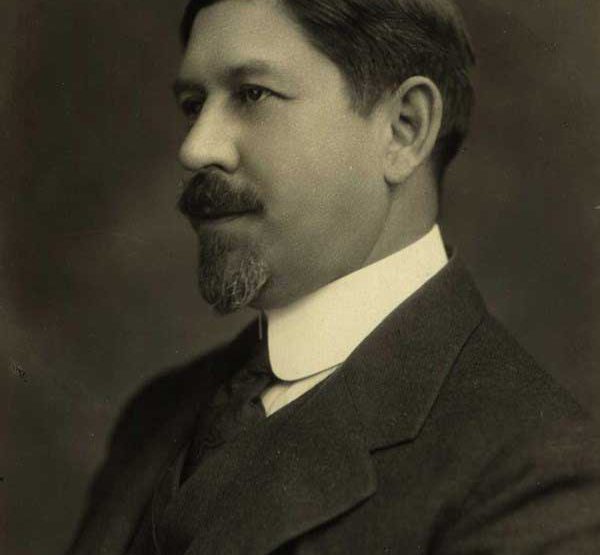

Jacobs, Samuel William, lawyer, author, philanthropist, and politician; b. 6 May 1871 in Lancaster (South Glengarry), Ont., son of William Jacobs, a horse-dealer, and Hannah Aronson; m. 23 April 1917 Amy Stein in Baltimore, Md, and they had four children; d. 21 Aug. 1938 in Montreal and was buried there two days later at Shaar Hashomayim synagogue.

Samuel William Jacobs was descended from a Jewish family that had emigrated from Russia at the beginning of the 1860s. The family took up residence in Ontario and in 1882 settled in Montreal. Jacobs embarked on his secondary education at the High School of Montreal in 1886 and then from 1890 to 1893 attended the faculty of law at McGill University, where he obtained his bcl. The following year he enrolled in law at the Université Laval in Montreal to improve his knowledge of French and he was awarded an llb in 1895. Jacobs was called to the bar of the province of Quebec in September 1894 and would be named kc in 1908. During the course of a legal career, pursued in Montreal, he formed partnerships with a number of colleagues, including Léon Garneau, Alexander Rives Hall, Gui-Casimir Papineau-Couture, and Louis Fitch. At the close of his professional life his partners would be Lazarus Phillips*, Lionel A. Sperber, Louis Mortimer Bloomfield, and Hyman Carl Goldenberg. In 1903 Jacobs published an annotated edition of the Code of Civil Procedure of the province of Quebec with his associate Garneau. His outstanding work, however, remains a voluminous monograph entitled The railway law of Canada (Montreal, 1909), which examines a body of legislation that was going through significant development at the turn of the century.

Jacobs had a diverse practice that encompassed civil, commercial, public, and criminal law. As one of the first lawyers to come from the Jewish community, he was frequently called upon to represent his co-religionists. Over the years he took part in famous trials in which he defended, in particular, the rights of minorities. His colleagues elected him treasurer of the Montreal bar for the year 1916–17.

At the beginning of the 20th century the growth of the Jewish population presented the problem of integrating its children into Quebec’s denominational school system. Indeed, the system, being divided into two networks, one Roman Catholic and the other Protestant, hardly facilitated the integration of Jews. The latent difficulty erupted publicly when the Protestant Board of School Commissioners of the City of Montreal refused a scholarship to Jacob Pinsler, whose Jewish father owned no property and consequently paid no school taxes. In charge of the case, Jacobs sued to compel the school board to award young Pinsler the scholarship. The claim was rejected by Quebec’s Superior Court in 1903. Amédée Robitaille, a Liberal mla and the provincial secretary, introduced legislation, enacted the same year, which resulted in a guarantee that Jewish pupils would be accorded the same rights and treatment as Protestants. This initiative was far from being the end of the matter: the issue of Jewish schools would persist for many years.

Jacobs was also connected with the case of the notary Jacques-Édouard Plamondon*. In 1910 the latter had given a talk of an anti-Semitic nature in Quebec City that was subsequently disseminated in pamphlet form by the printer René Leduc. The Jewish community took the matter seriously. Louis Lazarovitz, president of the Congregation Bais Israel, and Benjamin Ortenberg, a merchant, sued the speaker and the printer for damages for defamatory libel. Jacobs, one of the three Montreal lawyers representing Lazarovitz, was the lead counsel in the case. He even looked after finding funds for the trial within the Montreal Jewish community. At the end of the hearing in May 1913, he delivered his oral argument for the plaintiffs. At the outset he maintained that the case was not a simple conflict of opinion between a Catholic and a Jew: it was a matter of law and, for this reason, must be resolved in the legal realm. Jacobs refuted Plamondon’s statements and cast doubt on the credibility of the defence witnesses. He made certain to remind the court that as early as 1832 the province of Lower Canada had recognized that Jews have the same rights as other citizens, which was the first such acknowledgement in the entire British empire. He called this law the Magna Carta of Canada’s Jews. The plaintiffs’ case was dismissed at trial, but they won on appeal in December 1914.

Jacobs also represented Annie Langstaff [Macdonald*], the first woman to earn a law degree in Quebec, in her fight to join the bar. Langstaff was a court stenographer attached to his own practice, and completed her legal studies at McGill University in 1914. Like her colleagues she wanted to take the bar exams without delay. The board of examiners for the bar refused her application. The case was then referred to the civil courts for a ruling. Jacobs represented Langstaff, and in January 1915 asked Quebec’s Superior Court to compel the bar to let her sit the exams. Her case was dismissed in first instance and the lawyer took it to appeal, but he was again unsuccessful in winning over the majority of the court, which turned down the appeal in November. In February 1916 mla Lucien Cannon took the initiative of introducing a bill that would amend the statute governing the bar so as to allow the admission of women. The bill was studied by a committee of the assembly, which heard witnesses. Jacobs came forward and argued with conviction the case for women. The bill failed to garner a majority of votes.

In addition to practising law, Jacobs took an active part in the life of the Jewish community, both in Montreal and in the rest of Canada. Aware of the importance of creating greater cohesion within this group and of countering anti-Semitism, he and the businessman Lyon Cohen had founded the semi-weekly Jewish Times (Montreal) in 1897. Throughout his life he was engaged in many philanthropic organizations. With the aim of assisting Jewish immigrants to settle in Canada, he helped organize the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society of Canada, of which he would be honorary president from 1920 to 1938. He was the president of the Baron de Hirsch Institute and Hebrew Benevolent Society of Montreal from 1912 to 1914, and of the Canadian Jewish Congress from 1934 to 1938. In carrying out these responsibilities he established relationships both in Canada and abroad. With the rise of anti-Semitism, Jacobs made it a point of honour to demonstrate his indignation whenever he witnessed reprehensible behaviour towards Jews, especially following the publication of anti-Semitic articles in the press.

A highly visible leader in the Jewish community, Jacobs was also a voice for the demands it presented to the provincial government. In 1904 he persuaded Liberal mla Lomer Gouin* to use his good offices to amend the marriage-licence bill to facilitate Jewish marriages. In the legislation adopted in 1907 on the observance of Sunday as a day of rest, a dispensation was granted to Jews who observed the sabbath. In 1909, on the question of Jewish schools, Jacobs pressed for better representation of Jews in the school system.

A Liberal candidate in the federal election of December 1917, Jacobs was elected mp for the Montreal riding of George-Étienne Cartier, which included a large population of Jewish origin. Re-elected five times, he spoke for his constituents until his death. He was one of the first Jews to sit in the House of Commons, where he chaired the public-accounts committee from 1926 to 1930. He was recognized as a talented speaker. Endowed with a rare sense of humour, he was dubbed the Mark Twain of the house. Despite his popularity, he was not appointed to the cabinet, an omission that displeased the Jewish community. Regardless of his seniority, he was not invited to join the delegation that went to London to attend the 1937 coronation of King George VI, an exclusion that was seen as proof of anti-Semitism by Jacobs, the Montreal Gazette, and the city’s Jews.

In the course of his political career, Jacobs took an active part in parliamentary work. He often spoke in the house and participated in committees. Although he was a member of the opposition, shortly after he was first elected he put forward a bankruptcy bill that was taken up by the government and passed in 1919. Jacobs declared himself in favour of the equality of men and women before the law when, in 1924, mp Joseph Tweed Shaw proposed a resolution requesting the presentation of a bill that would make the grounds for divorce identical, regardless of the petitioner’s sex. Jacobs’s interest in electoral procedures led him to draw up legislative amendments. On 23 April 1931 he introduced a private members’ bill to abolish the requirement that an mp stand for re-election after being appointed to the cabinet. The bill was adopted by the government and passed by the house that year.

The stature he acquired as a parliamentarian enabled Jacobs to act frequently as a representative of his community and to defend its interests, particularly with respect to immigration. In a speech given in 1920 he identified problems that, in his opinion, needlessly complicated immigration to Canada. He also spoke out against the preference given to immigrants of Anglo-Saxon origin. He emphasized the advantage of a liberal policy, which, by favouring population growth, would help to ease the burden of Canada’s public debt. During the 1920s and 1930s, a period of restricted immigration, Jacobs, often accompanied by community leaders, interceded for his co-religionists with civil servants or ministers to obtain dispensations from rigid application of the law. In some years his efforts allowed the entry of a few thousand Jews. This concern, however, was not widely shared, especially during the economic crisis of the 1930s. Jacobs was sometimes criticized in the press by, among others, extreme right-wing papers (the Montreal weekly Le Patriote, for example). He had ties to the business world, and was on the board of directors of the Montreal Life Insurance Company, the Laurentian Insurance Company, and the Textile Company of Canada Limited.

Samuel William Jacobs had a remarkable career as a lawyer, during the course of which he won fame particularly for defending the rights of minorities. His renown made him an obvious candidate for the House of Commons. He did not, however, content himself with this personal success and strove through numerous initiatives to help his community. Such extraordinary dedication explains why he quickly became one of the great leaders of the Canadian Jewish community.

Samuel William Jacobs is also the author of The Quebec Jewish libel case … (Montreal, 1913) and “A Canadian Bankruptcy Act – is it a necessity?,” Canadian Law Times (Toronto), 37 (1917): 604–9. The book that he wrote with Léon Garneau is titled Code of Civil Procedure of the province of Quebec: text French and English … (Toronto and Montreal, 1903). Jacobs’s birth registration, issued 15 Nov. 1917, was added to the 1871 register, and is held at the BANQ-CAM, CE601-S96.

Alex Dworkin Canadian Jewish Arch. (Montreal), P0093. BANQ-Q, TP9, S1, SS5, SSS1, dossier 940 (1914) (Ortenberg c. Plamondon) (versement 1960-01-352/157); TP11, S1, SS2, SSS1, dossier 778 (1910) (Ortenberg c. Plamondon) (versement 1960-01-053/563). LAC, R4654-0-5. Le Devoir, 22 août 1938. Gazette (Montreal), 22, 23 Aug. 1938. La Presse, 24 août 1938. Irving Abella and Harold Troper, None is too many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933–1948 (Toronto, 1983). Herman Abramowitz, “Samuel William Jacobs,” American Jewish Year Book (Philadelphia), 41 (1939–40): 95–110. L.‑P. Audet, Histoire de l’enseignement au Québec (2v., Montréal et Toronto, 1971). S. [I.] Belkin, Through narrow gates: a review of Jewish immigration, colonization and immigrant aid work in Canada (1840–1940) ([Montreal, 1966]). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1918–1938. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Canadian Jewry, prominent Jews of Canada …, ed. Zvi Cohen (Toronto, [1933]). The Canadian law list (Toronto), 1913. Arlette Corcos, Montréal, les Juifs et l’école (Sillery [Québec], 1997). Bernard Figler, Sam Jacobs, member of Parliament (Samuel William Jacobs, k.c, m.p.) 1871–1938 (Ottawa, 1970). Gilles Gallichan, Les Québécoises et le barreau: l’histoire d’une difficile conquête, 1914–1941 (Sillery [Québec], 1999). J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise, vol.4. Histoire du catholicisme québécois, sous la dir. de Nive Voisine (2 tomes en 4 vol. parus, Montréal, 1984– ), tome 3, vol.1 (Jean Hamelin et Nicole Gagnon, Le XXe siècle (1898–1940), 1984): 177–215. The Jew in Canada: a complete record of Canadian Jewry from the days of the French régime to the present time, comp. A. D. Hart (Toronto and Montreal, 1926). Joe King, From the ghetto to the Main: the story of the Jews of Montreal, ed. Johanne Schumann, intro. Graeme Decarie (Montreal, 2001). Jacques Langlais and David Rome, Jews & French Quebecers: two hundred years of shared history, trans. Barbara Young (Waterloo, Ont., 1991). Langstaff c. Bar of the province of Quebec (1915), Rapports judiciaires officiels de Québec, Cour supérieure (Montréal), 47: 131. Langstaff (Macdonald) c. Bar of the province of Quebec (1916), Rapports judiciaires officiels de Québec, Cour du banc du roi (Québec), 25: 11. Mario Nigro and Clare Mauro, “The Jewish immigrant experience and the practice of law in Montreal, 1830 to 1990,” McGill Law Journal (Montreal), 44 (1998–99): 999–1046. “A noble roster”: one hundred and fifty years of law at McGill, ed. I. C. Pilarczyk (Montreal, 1999). Sylvio Normand, “L’affaire Plamondon: un cas d’antisémitisme à Québec au début du XXe siècle,” Les Cahiers de droit (Québec), 48 (2007): 477–504. Ortenberg v. Plamondon (1913), Dominion Law Reports (Toronto), 14: 549. Ortenberg c. Plamondon (1915), Rapports judiciaires officiels de Québec, Cour du banc du roi (Québec), 24: 69–78, 385–88. “The Plamondon case and S. W. Jacobs”, comp. David Rome, Canadian Jewish Arch. (Montreal), nos.26–27 (1982). J.‑É. Plamondon, Le Juif: conférence donnée au Cercle Charest de l’A.C.J.C., le 30 mars 1910 (Québec, [1910?]). G.‑É. Rinfret, Histoire du barreau de Montréal (Cowansville, Québec, 1989). G. [J. J.] Tulchinsky, Taking root: the origins of the Canadian Jewish community (Toronto, 1992).

Sylvio Normand, “JACOBS, SAMUEL WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jacobs_samuel_william_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jacobs_samuel_william_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sylvio Normand |

| Title of Article: | JACOBS, SAMUEL WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |