Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BURKE, EDMUND, architect; b. 31 Oct. 1850 in Toronto, son of William Burke, a lumber merchant and builder, and Sarah Langley; m. 27 July 1881 Minnie Jane Black, daughter of Joseph Laurence Black*, in Sackville, N.B., and they had three daughters and a son; d. 2 Jan. 1919 in Toronto.

Edmund Burke was the eldest of six children. His education began at Jesse Ketchum School in Toronto, and then, from 1863 to 1865, continued at Upper Canada College, where he placed near the top of his class. At age 14 he was indentured to his uncle, Toronto architect Henry Langley*. He supplemented his training with evening classes in mathematics at the Mechanics’ Institute. In 1872 Burke entered into partnership with his uncle, an association that was formalized the following year.

Ecclesiastical architecture formed the mainstay of Langley’s practice, so Burke’s expertise in the field was assured. His first important commission – Jarvis Street Baptist Church (1874–75) – reveals an exceptional level of maturity and independence from his mentor. Financed by Burke’s chief patron and a fellow Baptist, Senator William McMaster*, it included one of the earliest church amphitheatres in Ontario, together with a Sunday school made up of radial classrooms, modelled on the famous Akron plan devised by American bishop John Heyl Vincent. McMaster’s American-born wife, Susan, and her nominee for Jarvis Street, the Reverend John Harvard Castle* of Bond Street Baptist Church, appear to have been instrumental in choosing this scheme. Subsequent versions of the plan were remarkable not only for their stylistic variation, but also for the magnitude of their unsupported interior spans. Notable examples are Sherbourne Street Methodist Church (now St Luke’s United) of 1886–87, seemingly one of the earliest structures in Toronto to explore the Romanesque Revival style of American architect Henry Hobson Richardson; Trinity Methodist Church (now Trinity-St Paul’s United) of 1887–89, with an impressive interior defined by four giant arches beneath a lantern roof; and Walmer Road Baptist Church of 1892, a curious arts and crafts amalgam of red brick, a tile-hung clerestory, and rusticated stone.

By contrast, residential works by Langley and Burke of the same period demonstrated a full range of eclectic or “Queen Anne” styling. Those domestic works with which Burke alone can be associated often drew upon the ideas of British architect Richard Norman Shaw. Burke compressed Shaw’s grand, flexible plans into orderly rectangles that conserved heat and oriented each room to catch sunlight. On the exterior, eclectic details such as shingles, terracotta, and decorated bargeboards – all of which Shaw had helped make fashionable – added life to the monotonous idiom of the city’s red-brick town houses. Toronto retailing entrepreneur Robert Simpson* and prominent Baptists Daniel Edmund Thomson and Charles Joseph Holman were among Burke’s clients. The American shingle style, an analogue of “Queen Anne,” was used by Burke’s firm for cottages at Lome Park near Port Credit and later for houses in Sackville and Halifax.

In 1880–81 a second commission for McMaster – McMaster Hall, built to house the Toronto Baptist College and now the Royal Conservatory of Music – combined elements of Richardsonian Romanesque, “Queen Anne,” and High Victorian Gothic in a bold but not altogether satisfactory exploration of eclecticism. In the Army and Navy Store on King Street East, executed in two phases between 1887 and 1890, Burke achieved a more considered synthesis of traditional motifs and utilitarian materials when he framed a three-storey, plate-glass façade within a single monumental arch. This propensity for innovation challenged the traditions of the Langley office, where, by 1890, Burke was design partner. In 1892, faced with the entry of Langley’s son into the firm and despite a deepening economic recession, Burke struck out on his own, purchasing the prestigious practice of the late William George Storm*.

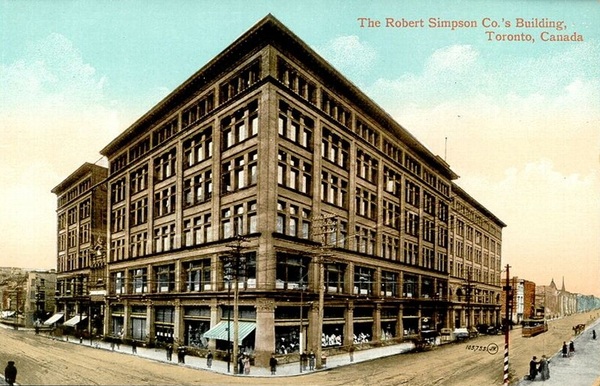

Almost immediately, two landmark commissions signalled radical departures in Burke’s work. First was the Owens Art Gallery (1893) at Mount Allison College in Sackville, where his awareness of contemporary American developments surfaced once more. In a powerful study of beaux-arts eclecticism, he conceived a severe, windowless façade that recalled the solemnity of an ancient Hellenistic mausoleum. This study anticipated the success of the architectural ideas employed for the Court of Honor at the Columbian exposition in Chicago later the same year. Burke’s second commission – the Robert Simpson store in Toronto (1894) – introduced a building style and technology perfected in the skyscrapers of Chicago. In Canada, load-bearing walls were still the rule, so the use of an open, fenestrated grid of narrow brick piers borne at the level of the mezzanine on a series of metal I-beams was a significant departure. The engineering challenges of this type of construction were formidable, but Burke was assisted by informative correspondence from another former Langley student, John Charles Batstone Horwood, who was completing his studies in New York. In December 1894 Burke and Horwood became partners.

A few months later Burke’s masterpiece was destroyed by arson, but Simpson immediately retained his firm to rebuild the store, this time with the fireproofing that Simpson had initially overruled. It was a turning-point in Canadian architecture: after intensely resisting new materials and methods, the Canadian profession came to terms with skyscraper technology, which would eventually lead architecture in Canada to the economical aesthetic of modernism. The reputation of Burke and Horwood in the field of retail design was made. In 1910, when the Hudson’s Bay Company sought architects to design three flagship stores in western Canada, it retained Burke, Horwood, and White – the third partner was Murray Alexander White – in preference to the well-known firm of Daniel Hudson Burnham of Chicago.

At a time when architecture had yet to achieve formal professional recognition in Canada, Burke’s commitment to organization, education, and standards is significant. As early as 1874 he was elected to the newly formed Ontario Society of Artists; two years later he was among those who tried, unsuccessfully, to establish an architects’ association. In 1887, when the Architectural Guild of Toronto came into being, he served on its executive. He then participated, in 1889, in founding the Ontario Association of Architects, which he served as president (1894, 1905–7), as examiner and instructor for many of its educational programs, and for years as chair of its Toronto chapter. In 1906–7 he also sat on the federal board of assessors appointed to select, from an open competition, a design for departmental buildings in Ottawa. When a bitter dispute erupted over the government’s appropriation of ideas submitted by the competing architects, Burke was among those who responded by setting up the Architectural Institute of Canada in 1907. At its first general assembly, in Ottawa the following year, he was elected a vice-president. He served on the Toronto Technical School Board, belonged to the Engineers’ Club of Toronto and the Royal Institute of British Architects, and was an associate member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and vice-president of the Toronto Guild of Civic Art, which involved him extensively in city planning.

Burke’s sober nature, prudent methodologies, and determination to keep abreast of modern developments, along with his tireless public service, earned him the regard of his colleagues and placed him at the forefront of the architectural profession in Canada. In politics he was a Liberal who none the less supported the Conservatives’ National Policy of protective tariffs. According to Henry James Morgan, Burke believed “that Can[ada] should be a united nation, free from sectarian or class distinctions, and for this reason [he] is opposed to a dual language and separate schs.”; “all labour questions affecting [the] genl. public” should, he maintained, be resolved by “compulsory arbitration.” In Toronto he belonged to the National, Canadian, and Rosedale Golf clubs, and served for many years at Jarvis Street Baptist Church as a Sunday-school teacher, chair of the choir committee, and deacon.

Edmund Burke’s unexpected death from pneumonia in 1919 produced a deep sense of loss. The board of the Ontario Association of Architects eulogized his moral rectitude, painstaking care, and altruism, and, more personally, his kindness of heart and graciousness of manner, which had often been tested in acrimonious debate. Survived by his wife and their three daughters, he was interred at Mount Pleasant Cemetery, for which, in 1893, he had designed the mortuary chapel.

The main repositories for drawings from the firms in which Edmund Burke was a partner are AO, Architectural Drawings Coll., C 11 (Horwood coll.); MTRL, SC, Henry Langley papers; Canadian Baptist Arch., McMaster Divinity College (Hamilton, Ont.); PAM, HBCA; City of Vancouver Arch., Add. mss 787 (plans for the Hudson’s Bay Company store in Vancouver); and ANQ-M, P-147 (coll. des plans d’architecture).

Writings by Burke or details concerning his career appear in Allisonia (Sackville, N.B.); American Architect and Building News (Boston); Beaver; Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto); Civic Guild of Toronto, Monthly Bull.; Construction (Toronto); and McMaster Univ. Monthly (Toronto).

AO, C 11, MU 3985, indentures of agreement, 1871–1909; F 1140; F 1403; RG 22-305, nos.13364, 37398; RG 55-17-63, no.694 CP. Art Institute of Chicago, D. H. Burnham letter-books. City of Toronto Arch., RG 5, F, building permits; RG 242 (Civic Improvement Committee), report, 28 Dec. 1911. Mount Allison Univ. Arch. (Sackville), Mount Allison Univ., Board of regents, minutes of meetings, 31 May, 8 Aug. 1893. Mount Pleasant Cemetery (Toronto), Burial records and tombstone inscription. MTRL, SC, Civic Guild of Toronto papers; Picture Coll. NA, RG 11, 4239, file 1298-1; RG 31, C1, 1861, Toronto, St Andrew’s Ward: 1108; 1871, St Andrew’s Ward: 2; St David’s Ward: 9; 1881, St Thomas’s Ward: 19. PANB, RS 159, 15/4: 420, no.8093. Private arch., Robert Hill (Toronto), “The biographical dictionary of architects in Canada, 1800–1950,” ed. Robert Hill (research project in progress). UCC-C, Church records, Toronto Conference, St Luke’s United (Toronto), Sherbourne Street Methodist, board of trustees, minutes, 1871–94; Trinity Methodist/United (Toronto), board of trustees, September–October 1887. UTA, A74-0018/96. Evening Star (Toronto), 4, 15 March, 13 April 1893. Globe, 3 Jan. 1919. Toronto Daily Mail, 29 Dec. 1876. Toronto Daily Star, 3 Jan. 1919. E. [R.] Arthur, Toronto, no mean city, revised by S. A. Otto (3rd ed., Toronto, 1986). Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1907–13. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). A. [K.] Carr, “From William Hay to Burke, Horwood & White: a case history in Canadian architectural draughting style,” Soc. for the Study of Architecture in Canada, Bull. (Edmonton), 15 (1990), no.2: 41–51; “‘On the highest plane of his possibilities’: the career of Toronto architect Edmund Burke (1850–1919)” (phd thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1990); Toronto architect Edmund Burke: redefining Canadian architecture (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1995). Kelly Crossman, Architecture in transition: from art to practice, 1885–1906 (Kingston and Montreal, 1987). William Davies, Letters of William Davies, Toronto, 1854–1861, ed. W. S. Fox (Toronto, 1945). William Dendy et al., Toronto observed: its architecture, patrons, and history (Toronto, 1986). Directory, Toronto, 1850/51, 1878, 1889, 1913. Institute of Architects of Canada, First report of the secretary to the provisional board for 1907 meeting ([Toronto?, 1907?]; copy at the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, Ottawa). Macmillan encyclopedia of architects, ed. A. K. Placzek (4v., New York and London, 1982), 1: 341. Geoffrey Simmins, Ontario Association of Architects: a centennial history, 1889–1989 (Toronto, 1989). Toronto, Board of Trade, “A souvenir”: a history of the growth of the Queen City and its board of trade, with biographical sketches of the principal members thereof (Montreal and Toronto, 1893); City Council, Minutes of proc., 1910–11; Mechanics’ Institute, Annual report, with an abstract of the proceedings of the annual meeting, 1866–67. Toronto Guild of Civic Art, Report on a comprehensive plan for systematic improvements in Toronto ([Toronto], 1909). A village within a city: the story of Lorne Park Estates (Cheltenham, Ont., 1980).

Angela K. Carr, “BURKE, EDMUND (1850-1919),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burke_edmund_1850_1919_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burke_edmund_1850_1919_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Angela K. Carr |

| Title of Article: | BURKE, EDMUND (1850-1919) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |