Source: Link

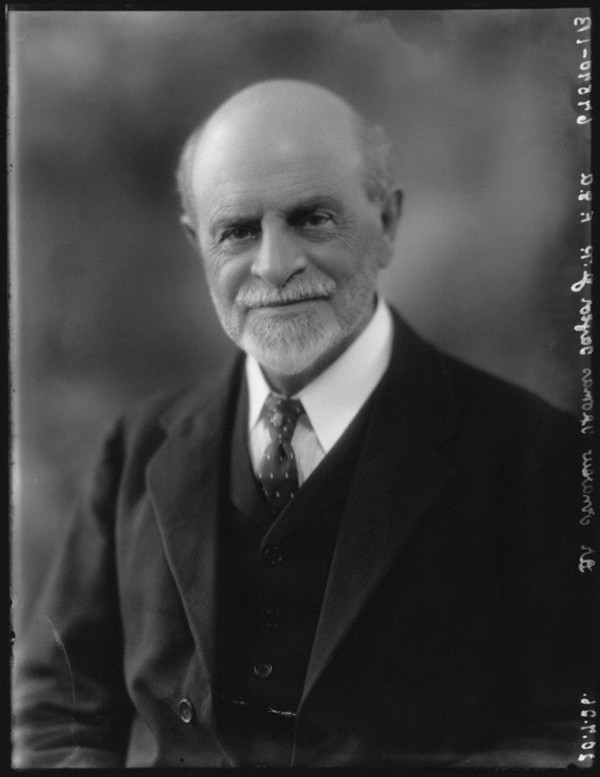

TAYLOR, Sir ANDREW THOMAS, architect, university lecturer, politician, and educational administrator; b. 13 Oct. 1850 in Edinburgh, son of James Taylor, a printer and publisher, and Agnes Drummond; m. 5 Dec. 1891 Mary Elliott (d. 1925) in Lambeth (London), England; they had no children; d. 5 Dec. 1937 in Hampstead (London), England.

Andrew Thomas Taylor’s maternal grandfather, George Drummond, had been an Edinburgh builder and contractor, a circumstance that perhaps influenced his own decision to become an architect. Following the accepted route into the profession, Taylor began a five-year pupillage in 1864 with an Edinburgh firm, Pilkington and Bell, known for its progressive Gothic Revival work. In 1869 he moved to Kelso, where he spent 18 months working for the Duke of Roxburghe’s estate architect. From that position he sought urban experience in the employ of William Smith, city architect of Aberdeen. In 1872 he entered the London office of Joseph Clarke, a prominent Gothic Revivalist who specialized in church design and restoration as well as in the design of schools. In his spare time Taylor attended classes at the Royal Academy Schools and at the Architectural Association and supplemented these studies with sketching tours in Britain and on the Continent. Admitted as an associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1878, he would win three of its medals by 1881. The last award was presented for an essay that was published as The towers and steeples designed by Sir Christopher Wren … (London, 1881).

Taylor opened his own practice in London in 1879. His first notable commissions, a chapel and school for a Baptist congregation in Dover (1880–81) and a row of almshouses in Chislehurst (London) (1881), both reflect the flexible medievalism of the late Victorian Gothic Revival and, in the case of the almshouses, Old English, a new style popularized by London architect Richard Norman Shaw. In 1882, with Henry Hall, he won second place in the important competition for the Glasgow Municipal Buildings. That year he took on a partner, George William Hamilton-Gordon. Now with an associate who could run the London office, in 1883 he opened a branch of his firm, known as Taylor and Gordon, in Montreal, where he had close relatives. During the previous year he had travelled to the United States to study recent work in such cities as Boston and New York. This tour gave him an exceptional grasp of current American styles and technology that would serve him well in Canada.

Taylor’s career in Canada, from 1883 to 1904, would benefit from the country’s growth as well as from family connections. His maternal aunt Jane Drummond was the widow of John Redpath*, founder of the Province of Canada’s first sugar refinery. His maternal uncle George Alexander Drummond*, who had also married into the Redpath family, was one of the nation’s foremost industrialists and financiers. Taylor’s links to leading members of Montreal’s English-speaking community would provide an invaluable source of patronage.

The most significant among Taylor’s early commissions was the renovation and redecoration (1884–86) of a landmark, the Bank of Montreal’s monumental head office on St James Street (Rue Saint-Jacques), designed by John Wells in 1845. Taylor’s uncle George, a director of the institution, oversaw the project, which called for the enlargement of the banking room to nearly twice its original size without significant change to the historic exterior and for extensive interior decorations. The ornamentation, described by the Gazette (Montreal) as being “in a style quite new to this part of the world,” was executed by Herter Brothers, decorators and cabinetmakers whose work had impressed Taylor in New York. The bank’s subdued decor was replaced with rich, warm colours and materials that reflected the fashionable Aesthetic movement at its most luxurious. The renovations were innovative in another way: even before the city’s streets would be electrified in 1889 the bank produced its own electricity from engines and dynamos in the basement. For this complex assignment, Taylor took on an additional partner, Robert William Bousfield, who was associated with the firm until 1888.

It was expected that Taylor’s expansion would accommodate the head office for many years. Yet by 1900 even more space was needed. A further enlargement and redecoration (1901–5), the grandest Canadian bank commission of the time, was carried out by the celebrated New York architects McKim, Mead, and White, whose work Taylor admired. He served with them as associated architect, sharing the fees. Herter Brothers again carried out some interior work.

Between these two notable projects, Taylor had designed many branches for the Bank of Montreal and other Canadian banks across the country. His early edifices confidently broke with accepted classical modes in favour of the more picturesque Queen Anne and Romanesque revivals, whose colour, height, and lively rooflines gave distinction to a townscape. As fashions changed, especially after the 1893 Columbian exposition in Chicago, which Taylor visited, he created a series of classical structures and, finally, in Winnipeg, the Merchants’ Bank Building (1900–2), the city’s first tall office building, which had seven storeys and two electric elevators.

Equally up to date were Taylor’s ideas for residences. The first houses he constructed in Montreal had been built of red brick with some timber, tile, and plasterwork. They show English styles adapted to Canadian conditions, combining Queen Anne and Old English features, but simplified and boasting modern heating systems. His most prominent city house, a mansion for George Drummond in Montreal (1888–89), was in a robust Richardsonian Romanesque with touches of Scottish Baronial, reflecting his uncle’s Scottish heritage and Taylor’s great admiration for the famous American architect Henry Hobson Richardson.

For his country homes Taylor looked to what is known today as the Shingle style. Developed in the United States during the 1870s and 1880s, it was associated in its earliest, picturesque phase with Richardson and in its later, more formal manner with McKim, Mead, and White. Two houses Taylor had designed in the 1880s in the summer community of Petit-Métis (Métis-sur-Mer), Que., reflect the style’s initial phase, while a fashionable Colonial Revival design was chosen for the grand estates of banker Hugh Montagu Allan* in nearby Cacouna and for Drummond in what would become Beaconsfield, near Montreal. These projects both dated from the turn of the century. Taylor also tried his hand at a newer type of residence, the apartment building. One was the stylish Marlborough on Milton Street, the other intended for artisans in a working-class neighbourhood.

Taylor’s receptivity to new trends is perhaps nowhere more evident than on the McGill University campus, where in the 1890s he designed the Redpath Library and the three science buildings financed by William Christopher Macdonald*. These, together with large additions he conceived for the old Medical Building, made him the most important architect at McGill in the 19th century. Harmonizing greystone was chosen for all four, but otherwise the designs varied. Engineering and chemistry were given Renaissance treatments, but Romanesque, with its sturdy, round-arched forms, was chosen for the physics building to provide the stability needed for delicate experiments. Fitted with state-of-the-art equipment, this new structure and its facilities so impressed Ernest Rutherford, then at the University of Cambridge, that in 1898 he accepted McGill’s invitation to serve as the third Macdonald professor of physics.

The Redpath Library (1892–93), also in the Romanesque style, was Canada’s second university library building, preceded by the University of Toronto’s, which had opened in 1892. Indeed, the two were among the few free-standing libraries of any kind in the entire country. While Richardson’s handsome Romanesque libraries were surely influential, McGill’s library has greater affinities with his famous Trinity Church in Boston and demonstrates Taylor’s own background in flexible medieval design. The Redpath building successfully joined a great navelike reading room featuring a fine hammer-beam roof and large, round-arched windows to a modern, extendable stack wing, the second of its kind in Canada.

The Montreal Diocesan Theological College (1895–96) clearly illustrates Taylor’s Gothic Revival roots. A dormitory, classrooms, a library, and a chapel were required, so he looked to one of the century’s most innovative works, William Butterfield’s church of All Saints’ Margaret Street, in London, England, the paradigm of a modern urban religious complex intended to fit a restricted site. Like Butterfield, Taylor disposed independent but linked structures around a small courtyard, using a low wall topped by a Gothic arcade and pierced by a pointed gateway to seclude the ensemble from its busy surroundings. The materials – red pressed brick from La Prairie, Que., trimmed with buff Ohio sandstone set on a grey limestone base – subtly recalls the constructional colours beloved by Butterfield and other mid Victorians.

A second Anglican institution, Bishop’s College in Lennoxville (Sherbrooke), Que., was also the beneficiary of Taylor’s designs in the 1890s. A fire in 1891 had destroyed the main edifice and most of the chapel. First completed was an L-shaped, all-purpose school building in a plain brick Gothic, which harmonized with what remained. Restoration of the chapel continued through much of the decade, while in 1897 a new headmaster’s house and a gymnasium were constructed according to Taylor’s plans.

Various commissions serving medical and charitable needs figured in Taylor’s practice over the years. Among these were alterations to the Montreal General Hospital, whose benefactors included both John Redpath and his son Peter, and to the historic Notman house, originally designed by John Wells (1845), in order to transform it in 1894 into St Margaret’s Home for Incurables, a renovation funded by Drummond. Other projects included a new wing for the Protestant Hospital for the Insane, located in Verdun (Montreal) (1896), and the Jubilee Nurses’ Home (1897), a handsome villa-like structure, the residence for the Montreal General Hospital’s nursing staff. Further afield was the Ross Memorial Hospital (1901–2) in Lindsay, Ont., the gift of Montreal railway contractor James Ross*. The homelike, Georgian Revival exterior of red brick concealed a modern steel frame manufactured in Pittsburgh, Pa, and concrete floors.

One of Taylor’s most novel commissions was his design for the first crematorium in Canada (1901–2). Located in Mount Royal Cemetery, in Outremont (Montreal), this extremely contentious project, which clashed with Christian belief in the resurrection of the body, was pushed through by Sir William Christopher Macdonald, a strong advocate of cremation. A glass-roofed entrance hall that could be filled with flowers was especially welcome during long winters.

In 1892 Taylor had been called on to plan a large extension to the gallery of the Art Association of Montreal on Phillips square. The imposing addition provided ample space not only for the institution’s own exhibitions but also for those of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Taylor had become an associate of the RCA in 1885 and an academician in 1890; he showed his drawings and watercolours in various exhibitions and encouraged his Canadian colleagues to do the same.

Despite his busy, far-flung practice, Taylor spent countless hours seeking to improve the architectural profession in Canada. A founder and early president of the Province of Quebec Association of Architects, incorporated in 1890, he had recognized that dramatic changes in building types, materials, and technology demanded provision for adequate training as well as regulation of the profession. His efforts were critical in Macdonald’s decision in 1896 to endow a chair of architecture at McGill, which led to the creation of Canada’s first university architecture department. Over the years it would train some of the country’s major architects, including such internationally known figures as Arthur Charles Erickson and Moshe Safdie. Taylor himself taught architectural courses during his years in Montreal, serving as instructor in freehand and model drawing for the faculty of applied science at McGill and as lecturer in ecclesiastical architecture at the Presbyterian College of Montreal.

In 1904 Taylor retired and returned to England, where he embarked on a second career in public service. His Montreal firm carried on under the name of Taylor, Hogle, and Davis, run by two younger employees; Taylor’s early partner, Hamilton-Gordon, had been practising independently in England for some time. After settling in Hampstead, in 1908 Taylor won a seat on the London County Council, the city’s governing body. He would be a member until 1926, sitting on a number of important committees and acting as the LCC’s representative on the boards of numerous other organizations. He was mayor of Hampstead in 1922. Among the many institutions that he served, one stands out: University College, founded in 1826 as the first English establishment of higher education with a modern curriculum and no religious restrictions. Appointed by the LCC to the college committee in 1910, he worked with various bodies over the years and was the college’s delegate to the senate of the University of London from 1918 to 1935. Two of his bequests, the Sir Andrew Taylor Prize in Architecture and the Sir Andrew Taylor Prize in Fine Art, expressed his special interest in the Bartlett School of Architecture and the Slade School of Fine Art and continued into the 21st century.

Taylor’s years of service were widely recognized. In 1919 he was granted the Medal of the City of Paris, in 1926 he received a knighthood, in 1928 he was made an honorary fellow of University College, and in 1936 he was awarded the Honorary Freedom of the City of London, the highest honour bestowed by the city. His work in Canada was acknowledged in 1931 when he was made an honorary fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada; this distinction had been given only once before – to Governor General Lord Willingdon [Freeman-Thomas*].

At the time of Taylor’s death, a long-standing colleague on the LCC wrote, “He was outwardly austere, but with a soft heart easily touched by any tale of distress…. His greatest happiness was work. Ascetic and conscientious to a fault, a strict disciplinarian, he never spared himself.”

Taylor was one of a number of British-trained architects who sought opportunities in Canada during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although he benefited from links to some of the country’s most prominent families, his ultimate success was the result of his extensive training, his openness to current developments, and his efforts to improve the architectural profession.

GRO, Reg. of marriages, Lambeth (London), 5 Dec. 1891. Univ. College London Arch. (London), Council records, college committee minutes; Managing committee records, managing sub-committee minutes. Victoria and Albert Museum, Royal Instit. of British Architects Library (London), Drawings and Arch. coll., RIBA nomination papers, vol.6: 11; vol.9: 127. Gazette (Montreal), 29 April 1884, 24 July 1886, 26 Aug. 1897, 7 March 1898. Montreal Daily Star, 18 April 1891, 25 March 1893, 3 Nov. 1894, 4 July 1896, 14 May 1931. Times (London), 3 Dec. 1937. Canadian Architect and Builder (Toronto), 3 (1890): 116; 6 (1893): 104–5; 8 (1895): 96–97, plates 1, 3, 4 (between pp.98 and 99); 11 (1898): 27, plates 2a, 2b (between pp.210 and 211); 13 (1900): 4, plate 6 (between pp.8 and 9); 15 (1902): 64 (see also the corresponding illustration in the architects’ ed.), 146, 175, plate 1 (between pp.176 and 177). Canadian Contract Record (Toronto), 3 (1892–93), no.5: 2; 4 (1893–94), no.27: 2; 7 (1896–97), no.5: 2; 8 (1897–98), no.8: 2. R. G. Hill, “The biographical dictionary of architects in Canada, 1800–1950”: www.dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org (consulted 29 October 2013). Oswald Howard, The Montreal Diocesan Theological College: a history from 1873 to 1963 (Montreal, 1963). K. S. Howe et al., Herter Brothers: furniture and interiors for a gilded age (New York, 1994). P. F. McNally, “Dignified and picturesque: Redpath Library in 1893,” Fontanus (Montreal), 6 (1993): 69–84. R. M. Pepall, Montréal, 1912: building a beaux-arts museum (exhibition catalogue, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1986). Royal Instit. of British Architects, Trans. (London) (1882–83). F. Tillemont-Thomason, “The physics building at McGill University,” Canadian Magazine, 7 (May–October 1896): 425–34. S. [W.] Wagg, The architecture of Andrew Thomas Taylor: Montreal’s Square Mile and beyond (Montreal, 2013); “Bank of Montreal addition,” in Money matters: a critical look at bank architecture (New York and Montreal, 1990), 69–71.

Susan Wagg, “TAYLOR, Sir ANDREW THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/taylor_andrew_thomas_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/taylor_andrew_thomas_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Susan Wagg |

| Title of Article: | TAYLOR, Sir ANDREW THOMAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2014 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |