Source: Link

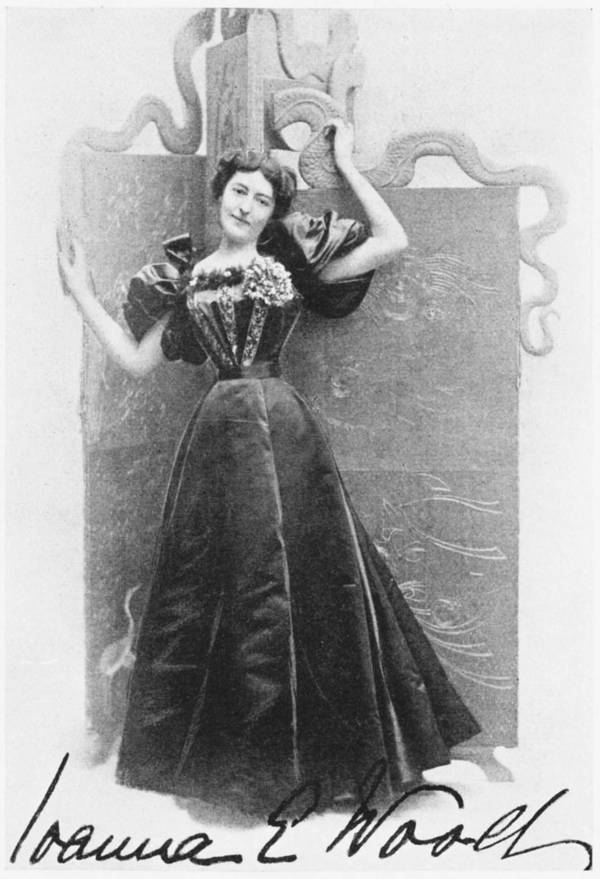

WOOD, JOANNA ELLEN, author; b. 28 Dec. 1867 in Lesmahagow, Scotland, daughter of Robert Wood and Agnes Tod; d. unmarried 1 May 1927 in Detroit.

Hailed as a Canadian Charlotte Brontë on the publication of her first novel in 1894, Joanna, also known as Nelly, Wood was celebrated in an article in the Canadian Magazine (Toronto) four years later as one of Canada’s “three leading novelists,” though “the least familiar.” Meteor-like, her career plunged into obscurity after 1902.

Wood was the youngest of 11 children. From a family long established in the isolated Scottish village of Slamannan, her father followed tradition to become a farmer, first as a tenant in Stirlingshire and then at Lesmahagow between 1862 and 1869, a period marked by the death of a number of his children from tuberculosis. In 1869 Robert, Agnes, and five surviving offspring followed the eldest son, William, to Irving, N.Y. They later moved to Ontario, possibly to be closer to Robert’s brother John Stanton Wood, who had settled near Guelph. In 1874 Robert purchased The Heights, a large, valuable farm overlooking the Niagara River at Queenston. Once settled, Robert and Agnes Wood became founding members of the Presbyterian church in nearby St Davids.

Reports suggest that Joanna was supported by her brother William, an insurance agent, following her education at the St Catharines Grammar School. Between 1887 and 1901 she was based in New York City, using William’s business address there for her mail while she travelled extensively to winter in various American or European cities and summer at Queenston. One of her journeys, to Scotland, enabled her to do research for her last known novel, Farden Ha’ (London, 1902), set in a Scottish coalmining village with a shaft under the owner’s house, as in Lesmahagow.

During a trip to England she had reputedly been presented at court by the sisters of poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, who was said to have been her fiancé. Two essays she wrote for the Canadian Magazine in 1901 fuelled these stories, sustained by family legend, but no archival evidence has been found. Moreover, given Swinburne’s greater age and homosexual leanings, an engagement is extremely unlikely. In her writing, however, Wood did espouse his aesthetics, with their fin de siècle decadence. Like him, she attempted to fuse the sensual with the spiritual through symbolism. Her absence from the Toronto literary scene created a vacuum in which such stories could circulate, mythologizing her within the dominant imperialist nationalism as a leading novelist who, like Charles George Douglas Roberts* and Horatio Gilbert Parker*, the other members of the triumvirate praised in 1898, was a Canadian Cinderella at home in English palaces.

Wood’s father had sold The Heights in 1893 to William, who later turned it over to Joanna; in addition, a neighbour bequeathed her an adjoining farm. According to the census of 1901, she lived at The Heights with her widowed mother, a niece, and two lodgers. The Canadian Magazine, however, corresponded with her in New York that year. In November 1906 Joanna sold the Queenston property and with her mother rented The Knoll on Regent Street in nearby Niagara-on-the-Lake. Joanna resided there more continuously, joining the Niagara Historical Society in 1907 and giving talks on “Reminiscences of Queenston” and “Impressions of Europe” a year later. In 1914 she was an absentee member of the society, resident in Buffalo, though she continued to visit friends in the Niagara area, among them historian Janet Carnochan and the Woodruffs of St Davids, the family of children’s writer Anne Helena Woodruff. In her letters to these friends Wood included poems.

How she had come to be a writer remains a mystery. Quotations in her fiction from the Romantics, Tennyson, Swinburne, and Shakespeare, and from female authors Mme de Staël, George Eliot, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Christina Rossetti on the “woman question” (in relation to women’s aesthetic and sexual yearnings for transcendence) imply that she was well read. They also connote serious literary ambitions. According to Honora S. Howard in the Buffalo Illustrated Express in 1896, Joanna attributed her success to her brother William, her first reader and a severe critic. Apparently on his recommendation she sought a publisher, finding in J. Selwin Tait a sympathetic fellow author who encouraged her to write a novel, which he launched in New York to extravagant praise. His blurb comparing Wood’s The untempered wind (1894) to Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The scarlet letter set the terms for subsequent reviews. Her second novel, Judith Moore . . . (Toronto), appeared in 1898. Most of her writings, reportedly quite numerous and many of them prizewinners, cannot be located. No trace can be found, for instance, of “The mind of God,” which took a $500 award according to the Canadian Magazine in 1898. Equally mysterious is the abrupt end to Wood’s burst of creative energy. No mention is made of her in the Canadian Magazine after 1901, not even reviews of Farden Ha’, perhaps because she no longer sent news-filled letters to its editor, John Alexander Cooper*.

At the pinnacle of her career in 1901, Wood was the highest paid Canadian fiction writer. Her work was also a critical success, especially her first two novels, though they were praised for different qualities. British reviewers commented that she “has a style,” which Americans attacked as overwrought. Characterization was what Canadians admired, along with her innovative “local colour realism,” inspired by English novelist Mary Russell Mitford. The Canadian Magazine, which praised her depiction of Ontario rural life in Judith Moore, later faulted A daughter of witches . . . (Toronto, 1900) for its American setting and forecast greater success had she included “local colour in the Canadian country scenes, with which the authoress is so familiar.” With her treatment of a Scottish village in Farden Ha’, in the tragic manner of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex fiction, Wood no longer fit easily into the mythology of the national landscape that had made her the darling of the Canadian Magazine.

This tension between cosmopolitanism and regionalism echoes the conflict between boundlessness and constraint in the plots of Wood’s novels. They use variations on the love triangle or two-suitors plot common in 19th-century fiction to trace the inward growth of powerful and unconventional heroines confronting the demands of social institutions. Desire, Wood’s central theme, is developed through an impressionistic use of landscape to generate powerful symbols. The fallen woman of The untempered wind, true to her vow of love, escapes through the night woods from the harassment of the narrow-minded women of Jamestown (likely modelled on Queenston); the diva of Judith Moore sings like a lark uncaged in an Ontario orchard, in a reworking of the plot of Corinne, ou l’Italie (a de Staël novel), which dramatizes the conflict for women between artistic triumph and romantic fulfilment. These works bow to convention by ending with marriage. Wood’s next two novels, A daughter of witches and Farden Ha’, deal with the disruptive effects of passion on the institution of marriage. The two novellas published in Tales from Town Topics (New York) highlight the decadent aspect of Wood’s fiction: “A martyr to love” (1897) recounts the adventures of a femme fatale ironically wounded in her heartless conquests, while “Where waters beckon” (1902) draws symbolically on Niagara’s whirlpools and local Indian legends as the setting for a dark tale of a woman married off to a madman by her father and later destroyed with her lover, an engineer developing hydroelectricity.

Americans recognized the feminist argument in Wood’s critique of patriarchal authority constraining women’s desire. However, they made a distinction between the “unconventional theories” in her writing and her fondness for “feminine frivolities” in her clothing. Current Literature (New York) insisted in 1894 that she was no “woman’s-righter.” In 1896 Honora Howard did not see her as a “new woman” since she supported neither the rational dress movement nor the suffrage movement. Yet Wood’s most enthusiastic review, of Judith Moore in 1898, came from a “new woman” journalist, Kit Coleman [Ferguson*] of the Toronto Daily Mail and Empire. Conversely, Wood’s relentless depiction of the persecution of the fallen woman in The untempered wind had been condemned as anachronistic and “half-hysteric” – negatively feminine – by another female journalist (possibly Laura Bradshaw Durand) in the Toronto Globe in 1894. As Wood confessed to William Kirby*, a Niagara correspondent, this “savage” review hurt because it came from a Canadian, and all the more so because the “poetic flight which smacks of the school-girl composition” attacked by the critic was a quotation from Shelley’s “Adonais.”

Wood’s short stories, in the New England Magazine (Boston), the Canadian Magazine, the Christmas Globe (Toronto), and elsewhere, are divided between controlled ironic renderings of local events centred on strong female characters, and masculine adventure stories from a “Mexican series,” which use legend and setting to create atmosphere and suspense. “Unto the third generation,” published anonymously in All the Year Round (London) in 1890 but attributed to Wood, recounts the effect on a young man of the revelation that his mad mother is locked up in a West Indian house, a topic with similarities to Jane Eyre. Among Wood’s unlocated stories, “The lynchpin murders” (announced in the Niagara Times in 1898) suggests that Wood continued to experiment with new fictional forms until she abruptly stopped publishing in 1902.

According to the Niagara Falls Evening Review in 1927, Wood had suffered a nervous breakdown some years before which had compelled her to abandon her writing. She had portrayed such a crisis in Judith Moore, invoking the pastoral myth when a stressed prima donna retreats to a village to recover her health and soul. This scenario poses intriguing questions. Was her brother William a hard taskmaster, like Judith’s New York manager? Did Joanna choose voluntarily to give up her artistic career, like Judith, in the name of emotional fulfilment? Her last recorded publication is a topical poem, “The man in the ranks,” in the St. Catharines Standard sometime between 1914 and 1917.

After her mother’s death in February 1910, Joanna Wood had resided with her brother William, then a life-insurance agent in New York City and later in Freeport, N.Y. She subsequently spent time with her sisters Mary Glennie in LaSalle, N.Y., and Jessie Maxwell in Detroit, at whose home she died of a stroke on 1 May 1927. She was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Niagara Falls, Ont.

Joanna Wood’s concern with women’s self-realization and symbolism has stimulated renewed interest in her work by late-20th-century feminist critics. As a result, The untempered wind was republished in a centenary edition in Ottawa in 1994.

Wood’s novel A daughter of witches was originally serialized in the Canadian Magazine (Toronto), 12 (November 1898–April 1899)–13 (May–October 1899). An excerpt from The untempered wind was published in Current Literature (New York), October 1894: 378 under the title “An inheritance of dishonor: a child’s sorrow,” and an excerpt from Judith Moore entitled “Sam Symmons’ great loss” appeared in the Canadian Magazine, 10 (November 1897–April 1898): 536–38.

Other stories and articles by Wood which have been located include “Malhalla’s revenge” in the New England Magazine (Boston), new ser., 12 (March–August 1895): 184–87; and “A mother,” “Algernon Charles Swinburne: an appreciation,” and “Presentation at court” in the Canadian Magazine, 7 (May–October 1896): 558–61 and 17 (May–October 1901): 2–10 and 506–10 respectively. Another story attributed to her, “The land of manana,” has not been found.

Reviews of The untempered wind appeared in Current Literature, October 1894: 298; the Globe, 10 Nov. 1894: 9; the New York Nation, 30 May 1895: 426; and the Toronto Week, 12 Oct. 1894: 1099. Judith Moore was reviewed in the Canadian Magazine, 10: 460–61; the Daily Mail and Empire, 19 March 1898: 4; and the Nation, 6 Oct. 1898: 264. Reviews of A daughter of witches can be found in the Canadian Magazine, 16 (November 1900–April 1901): 91–92 and 388–89; in three London publications – the Athenæum, 1 Sept. 1900: 276; the Bookman, October 1900: 28; and the Spectator, 8 Sept. 1900: 309; and in the New York Saturday Rev., 6 Oct. 1900: 432.

AO, F 1076-A-23. Brock Univ. Library, Special Coll. and Arch. (St Catharines, Ont.), Women’s Literary Club of St Catharines Arch., E. M. Stevens, J. E. Wood scrapbook. North York Central Library, Canadiana Coll. (Toronto), J. A. Cooper papers, Canadian Magazine files. Daily Record (Niagara Falls, Ont.), 2 March 1910: 3. Evening Review (Niagara Falls), 3 May 1927. H. S. Howard, “Joanna E. Wood,” Buffalo Illustrated Express (Buffalo, N.Y.), 26 Dec. 1896: 7. Niagara Advance (Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.), 28 Aug. 1919. St. Catharines Standard, 7 May 1927. Times (Niagara-on-the-Lake), 21 Oct. 1898: 5; 14 Feb. 1908: 1; 17 April 1908: 4; 4 March 1910: 1. Canadian Magazine, 11 (May–October 1898): 180, 270; 12: 473. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Wendy D’Angelo, “Joanna E. Wood: a ‘new woman’ and her works” (ba thesis, Dept. of English, York Univ., Toronto, 1987). Dictionary of literary biography (317v. to date, Detroit, 1978– ), 92 (Canadian writers, 1890–1920, ed. W. H. New, 1990). Barbara Godard, “‘Petticoat anarchist’?: Joanna Wood, the sex of fiction, the fictive sex,” in Women’s writing and the literary institution, ed. C[laudine] Potvin et al. (Edmonton, 1992), 95–125; “A portrait with three faces: the new woman in fiction by Canadian women, 1880–1920,” Literary Criterion (Bombay), 19 (1984), nos.3–4: 72–92. Carrie MacMillan, “Joanna E. Wood: incendiary women,” in Silenced sextet: six nineteenth-century Canadian women authors, ed. Carrie MacMillan et al. (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1992), 169–200. The Oxford companion to Canadian literature, ed. Eugene Benson and William Toye (2nd ed., Toronto, 1997). E. M. Stevens, “She’s Canada’s Charlotte Brontë, but Joanna E. Wood goes unrecognized here,” Early Canadian Life (Oakville, Ont.), 4 (1980), no.4: B3, B15; “Writers of the Niagara peninsula: Wood, Joanna Ellen,” Ontario Geneal. Soc., Niagara peninsula branch, Notes from Niagara (St Catharines), 4 (1984), no.2: 6. Types of Canadian women . . . , ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903).

Barbara Godard, “WOOD, JOANNA ELLEN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_joanna_ellen_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wood_joanna_ellen_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barbara Godard |

| Title of Article: | WOOD, JOANNA ELLEN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |