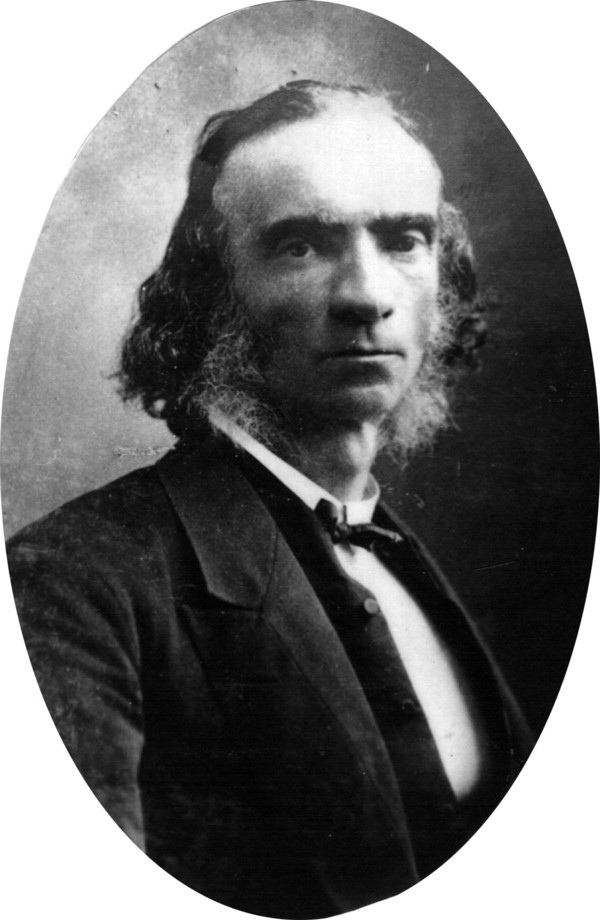

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WILSON, Sir DANIEL, artist, author, ethnologist, and university teacher and administrator; b. 5 Jan. 1816 in Edinburgh, son of Archibald Wilson, a wine merchant, and Janet Aitken; m. 28 Oct. 1840 Margaret Mackay (d. 1885), and they had two daughters; d. 6 Aug. 1892 in Toronto.

After attending the Edinburgh High School, Daniel Wilson entered the University of Edinburgh in 1834 but left the next year to study engraving with William Miller. In 1837 he went to London to establish himself as an illustrator and worked briefly for the painter J. M. W. Turner. Both in London and in Edinburgh, to which he returned in 1842, Wilson eked out a living through literary hack-work, producing reviews, popular books on the Pilgrim Fathers and on Oliver Cromwell and the Protectorate, essays for magazines, and art criticism for the Edinburgh Scotsman.

While still in his teens Wilson had taken to exploring and sketching the old buildings of Edinburgh. His Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (2v., Edinburgh, 1848) is profusely illustrated with his own woodcuts and engravings of picturesque structures and architectural details, and it contains an evocative but rambling history of the city. Wilson’s fascination with the past expressed a romantic feeling stimulated by the novels of Sir Walter Scott as well as a patriotic pride in the indigenous antiquities of Scotland, and it extended beyond the history that could be documented by written records to encompass much earlier relics and even skeletal remains. As honorary secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland from 1847, Wilson visited sites and corresponded extensively with collectors throughout the country. In 1849 he compiled a synopsis of the holdings of the society’s museum which, in turn, provided him with the outline for The archæology and prehistoric annals of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1851), the first comprehensive survey of Scottish archaeological remains and one that departed substantially from the tradition of merely gathering and cataloguing curious rarities. Wilson regarded such artefacts as weapons, ornaments, implements, and tombs as the historian’s equivalent of the geologist’s fossils: just as fossils enabled the scientist to identify and characterize eras in the earth’s history, so material remains enabled the student of prehistory (a word which he introduced into the English language) to document the sequence of ages in the human past and to infer attitudes, beliefs, and rites of long-vanished cultures. Wilson adopted the three-tiered division established by Danish antiquaries and arranged Scottish artefacts in terms of the stone, bronze, and iron ages. By connecting these ages to the Christian era, moreover, he drew links between archaeology and written history and thereby extended enormously the chronological depth of the country’s past. Through the examination of skeletal remains and the measurement of skulls Wilson showed that other peoples had lived in Scotland before the Celts. His book also constituted a protest against the tendency to attribute relics that showed skill of workmanship and invention to Roman or Scandinavian influences and to assign all that was rude to Britons, and a plea that archaeology, in order to assume the status of a science, be closely associated with ethnology and that data on Scotland be compared with material from other parts of the world.

Wilson’s book helped establish prehistory as a science in Great Britain as well as his own reputation as a scholar. In 1851 he received his only degree, an honorary lld from the University of St Andrews, and in 1853, despite slight academic experience, he was appointed to the chair of history and English literature in University College, Toronto. His application was supported by Lord Elgin [Bruce*], governor of the United Province of Canada and a fellow member of the Society of Antiquaries.

Wilson’s move to Canada accentuated some of his intellectual interests and closed off other lines of development. Although he kept abreast of discoveries in Scottish prehistory and reworked and reissued his books, he was removed from direct contact with source materials and co-workers. On the other hand he responded eagerly to the ethnological possibilities of the New World. His enthusiasm for the study of the North American Indians was reinforced if not ignited by some members of the Canadian Institute. Wilson joined this scientific society in 1853, edited its periodical, the Canadian Journal: a Repertory of Industry, Science, and Art (Toronto), between 1856 and 1859, and served it in many administrative positions, including that of president in 1859 and 1860. He was instrumental in broadening the scope of its reportage on science to include ethnology and archaeology, and even added literary criticism. Members of the institute had shown a determined interest in preserving the relics, languages, and lore of the vanishing Indians; some, such as painter Paul Kane*, explorer Henry Youle Hind*, and Captain John Henry Lefroy* of the Royal Engineers, had travelled extensively in the northwestern wilderness. Wilson grew especially fond of Kane and of his patron, George William Allan, who collected native artefacts. Wilson’s growing knowledge of the native peoples owed much more to the experiences, collections, and publications of his new acquaintances than to firsthand encounters, and he saw the native peoples in the light of his European preoccupations: they were important not in and for themselves but rather because they exemplified living, primitive cultures that had once existed in prehistoric Europe.

In his new environment Wilson’s early interests in cranial types and measurement grew into an obsession, largely in response to the controversy over whether the various races of people had separate origins (polygenesis) or had developed from a single creation (monogenesis). A group of American writers, including Philadelphia physician Samuel George Morton, an acquaintance of Wilson’s, ascribed mental and moral qualities to races on the basis of the shapes of heads, argued that races were distinct species, and contended that a single head type was to be found among all North American native peoples other than the Inuit. The implications of polygenesis, and its association with justifications of Negro servitude, offended Wilson’s moral sense as well as his scientific instincts. He had grown up in a family of pronounced anti-slavery views, and in 1853 in Philadelphia he was surprised and hurt to find that people dismissed as ridiculous the idea that “the black man is sprung from the same stock as the white.” All his life Wilson remained true to the cardinal doctrine of the philosophers of the late 18th-century Scottish Enlightenment that humankind was everywhere and in all ages the same and that variations of culture and attainments were due to the circumstances in which people were placed, not innate racial character. In a series of articles, Wilson challenged the view that a single head type characterized the North American Indian race by pointing out how varied specimens actually were and how difficult it was to generalize about skulls that had been altered by diet, deliberate deformation, and burial rites.

The twin themes of the unity of mankind and the importance of the indigenous native culture of North America for illuminating European prehistory dominated Wilson’s Prehistoric man: researches into the origin of civilisation in the Old and the New World (Cambridge, Eng., and Edinburgh, 1862). Its two discursive and synthetic volumes attempted to establish man’s innate capacity by examining how certain faculties or instincts were expressed among a great diversity of races and cultures. Thus Wilson wrote of water transport, metallurgy, architecture, fortifications, ceramic art, narcotics, and superstitions in order to illustrate the ways in which human beings revealed a common ingenuity in invention and in artistic and religious expression. His entire inquiry was based on the belief that despite an immense variety of cultures and conditions all people were capable of progress, that levels of attainment were matters of social learning and environment rather than biological destiny, and that progress was by no means inevitable because man was a free agent and could relapse into savagery. Wilson was especially intent on isolating parallels and correspondences between the cultures of North America and those of prehistoric Europe. In discussing sepulchral mounds, for example, he compared the funeral rites of an Omaha chief who was buried with his horse and those of an ancient Saxon interred with his chariot: “For man in all ages and in both hemispheres is the same; and, amid the darkest shadows of Pagan night, he still reveals the strivings of his nature after that immortality, wherein also he dimly recognizes a state of retribution.”

For Wilson there was no contradiction between the psychic unity of man and the fact that certain races, favoured by environment, were more advanced than others. He was intrigued by the cultural contacts between Amerindians and Europeans and by the resulting displacement and extinction of the weaker races. North America seemed to him a gigantic laboratory of racial intermixture, and he insisted that interbreeding had already taken place in Canada to a larger extent than was commonly recognized. Because the polygenists had argued that different species of people were incapable of perpetuating hybrids that would be permanently fertile, Wilson made much of the Métis of the Red River settlement whose offspring were, he felt, in some respects superior to the original stocks. The Métis also seemed to him to point to the fate of all the aboriginal peoples of Canada: they would ultimately disappear as distinct groups, not by extinction, but by absorption into a new type of humanity. Wilson was therefore highly critical of a policy that isolated Indians on reserves and kept them in a state of pupilage; he argued that Indians themselves should manage their reserves and resources, that they should as individuals have the right to dispose of their share of reserve lands, and that individuals should be freed to compete equally with whites.

Throughout his study Wilson dwelt upon the profound differences between human beings and animals. Unlike Charles Darwin, whose theory of evolution through natural selection attempted to explain the continuity of human and animal intelligence, Wilson contrasted man’s moral sense, and his capacity to reason, accumulate, and transmit experience, with the fixed, mechanical instincts of animals. Wilson also found fault with Darwin’s hypothetical mode of argument, pointed to the lack of geological evidence for transmutation, and objected to a scientific explanation of a reality that was both material and spiritual on material grounds alone. Though in time he accepted elements of the evolutionists’ argument – such as a vast age of the earth and a remote prehistory of man – and even conceded the possibility of man’s physical evolution, he always insisted on a special creation of man’s moral feelings, instincts, and intelligence.

A British reviewer of Prehistoric man was amazed that such a study issued from the “woody depths of Canada”; closer to home, Henry Youle Hind dismissed Wilson as an armchair anthropologist who relied excessively upon the observations of others. But, though Wilson did almost no field-work in Upper Canada’s prehistory (apart from a trip to Lake Superior in 1855 to examine ancient workings of copper deposits), he did travel to museums in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston to study Indian skulls. He also visited the impressive earthworks in the American Midwest which he, like most others, concluded were the products of a race of mound-builders who had been displaced by the Indians, and he made determined efforts to gather information by sending questionnaires to Indian agents. Still, Wilson’s originality lay more in calling the attention of European scholars to the evidences of the prehistory of the Old World that could be seen in North America, and in making the ideas of European anthropology better known in Canada. His book, however, appeared at a time when Darwin shifted the terms of the debate about man from the multiple or single creation controversy to the question of man’s descent from brutish ancestors. Wilson never fully engaged this problem, nor did he ever follow other anthropologists and ethnologists inspired by the theory of evolution in constructing stages of lineal social progress along which peoples were assigned positions on the grounds of racial capacity. His reluctance to pursue these lines of argument is perhaps why one of his students, the poet William Wilfred Campbell*, judged Wilson too old and conservative to be affected by the growth of science in the latter decades of the century. On the other hand modern anthropologists, who have freed themselves from the post-Darwinian obsessions with race, have found Wilson’s work refreshing and forward-looking precisely because he was in his own time so reactionary.

Prehistoric man drew together the main elements in Wilson’s eclectic anthropological and ethnological thought, and in his later papers, some of which were collected in The lost Atlantis, and other ethnographic studies (Edinburgh, 1892), he refined and qualified ideas already set out in it. He continued to write about migration and racial intermingling, the aesthetic faculty in aboriginal people, and the relationship of the size of the brain to intellectual vigour. He came to doubt that cranial capacity offered any reliable measure of intelligence. One of his minor interests was why most people were right-handed (Wilson was left-handed and became ambidextrous) and whether this preference was due to social habit or physiology. This seemingly trivial inquiry led him to consider evidence from archaeology, philology, literature, and anatomy, and to the conclusion that the left hemisphere of the brain, which controlled the right side of the body, developed earlier than the right hemisphere.

Wilson always seemed to have several projects under way simultaneously, not all of them tangential to the subjects he taught as professor of history and English literature. Though Caliban: the missing link (London, 1873) has most often been described as a playful comparison of Shakespeare’s imaginary creation, a being between brute and man, and the fanciful inventions of modern evolutionary science, it is no less a study of the dramatist’s artistry, the supernatural creatures in his plays, and the intellectual milieu in which he wrote. In Chatterton: a biographical study (London, 1869) Wilson documented the life of the young poet who had like himself sought fame and fortune in London but who had met only despair and death by his own hand. Of these two books and the third edition of Prehistoric man, published in 1876, Wilson said in 1881 that Chatterton was his favourite.

By this date Wilson’s energies were absorbed in university administration and academic politics. He misled his friends and possibly deluded himself when he confessed a preference for the quiet scholarly life, for he relished and excelled in the affairs of the University College council and the University of Toronto senate. His prominence in the university was already established in 1860, seven years after his arrival, when he, rather than the president of University College, John McCaul*, appeared with the vice-chancellor of the university, John Langton, before a select committee of the Canadian assembly to defend the college. In his testimony Wilson adumbrated the principles of higher education that would guide him as president of University College after 1 Oct. 1880 and as president of the University of Toronto from 1887 to 1892.

Under the University Act of 1853 the University of Toronto had become solely an examining and degree-granting institution with teaching being delegated to University College and to such denominational colleges as Victoria at Cobourg and Queen’s at Kingston which were expected to affiliate with it. The University of Toronto and University College had prior claims upon the revenues from the endowment first established for King’s College; any remaining surplus was to be divided by the government among the denominational institutions. However, with the construction from 1856 to 1859 of the quasi-Gothic University College building [see Frederic William Cumberland*], to which Wilson contributed designs for gargoyles and carvings, no funds were left to be shared. The cause of the denominational institutions was taken up by the Wesleyan Methodist Church which in 1859 requested the Legislative Assembly to investigate the alleged mismanagement of University College. At the select committee hearings held the next year, before which Wilson and Langton appeared, Egerton Ryerson*, the superintendent of education for Upper Canada, denounced the unjust monopoly of revenues intended for all colleges by this “temple of privilege” run by a “‘family compact’ of Gentlemen”; censured the wastage of public funds on a needlessly elaborate building; upheld as models the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, which concentrated on the classics and mathematics, in contrast to University College, which offered too many optional subjects in the sciences, history, and modern languages; and doubted that a Christian education was attainable in a godless institution in which teachers were not imbued with the feelings and principles of religion. Ryerson hardly endeared himself to Wilson by also mentioning that there was no need to teach history and English literature at the college level since these subjects were covered in the grammar schools.

In his response on 21 April 1860 Wilson endorsed the Scottish model of higher education, especially the teaching of abroad range of subjects and the provision of options that would help prepare students in practical ways for particular professions. Wilson was contemptuous of appeals to the examples of the two old English universities which were accessible only to a privileged class and some of whose graduates struck him as men who had “just emerged from the cloister.” Both he and Langton pointed to the unmistakable trend in Britain towards severing the denominational associations of universities and the removal of all restrictions on faculties other than the theological. On this matter Wilson spoke with considerable feeling: his brother George, a chemist, had for years been kept from a university position because he could not in good conscience sign the confession of faith and the formula of obedience of the established church in Scotland. Wilson detested the sectarianism of colonial society. He argued that public financial support for the religious colleges would perpetuate class and denominational differences, whereas in a non-denominational system people with different religious convictions would intermingle and be trained to cooperate.

Wilson’s support for the principle of nondenominationalism did not mean that he wanted to divorce religion in general from higher learning or that he was an outright secularist. He believed profoundly that, though there were many ways of attaining an understanding of God and nature, truth itself was one, and that science would supplement, not challenge, the essential teaching of Scripture. Thus, far from promoting an indifference to religion, Wilson attacked ecclesiastical interference in the teaching of science precisely because such intervention in the past had impeded the discovery of truth which was both secular and spiritual.

Like Ryerson, Wilson could not refrain from mixing statements of principle with personal abuse. He insinuated that since Ryerson did not possess a university degree he could not be taken as an informed witness on higher education, to which Ryerson replied that Wilson’s own academic experience in Scotland had been brief and his only degree was an honorary one. As for Wilson’s scholarship he added that Wilson had a particular affinity for relics and that “in his leisure moments in this Country [he] has devoted himself to disembowelling the Cemeteries of the Indian Tribes, in seeking up the Tomahawks, Pipes and Tobacco which may be found there, and writing essays upon them.”

Though the select committee issued no recommendations, the hearings left a lasting impression on Wilson. He conceived an intense distaste for Ryerson in particular – “the most unscrupulous and jesuitically untruthful intriguer I ever had to do with,” he confided in his journal – and a suspicion of Methodist designs against University College in general. All subsequent proposals for a closer association of the religious colleges, especially the Methodist Victoria, with the University of Toronto, appeared to Wilson as a revival of the attempt of 1860 to despoil University College. Wilson played no role in initiating in the mid 1880s the proposals for the federation of denominational colleges with the university and, had he had his way, University College would have remained the primary teaching arm of the university with the denominational colleges becoming merely centres for theological instruction. In the difficult and protracted negotiations over the terms upon which Victoria College would enter federation, Wilson’s role was one of obstruction and resistance. He had no appreciation for the creative possibilities of the principle of university federation (which in any case was only fully realized after his death) and little understanding of the risks its Methodist supporters undertook. For him federation was a Methodist plot abetted by politicians out to secure the Methodist vote.

Wilson’s life as president of University College and later of the University of Toronto was complicated by the fact that all appointments to the teaching staff were made by the government on the recommendation of the minister of education for Ontario, and that university statutes could take effect only with the minister’s approval. These arrangements maximized the opportunities for intrigue and interference both on the part of politicians responsive to the critics of the college and university and on the part of disaffected academics who could and did take their complaints to the minister. Wilson was frequently challenged on appointments by those who advocated the hiring of native-born Canadians (or even exclusively Toronto graduates), but the most illuminating example of the cross-pressures under which he worked was the issue of the admission of women to classes at University College. Their status was quite anomalous: after 1877 they could write the matriculation examinations but they could not attend classes or obtain degrees. In 1883 Wilson cavalierly rejected applications for admission by five women. Their cause was taken up by Emily Howard Stowe [Jennings*] and the Women’s Suffrage Association, by William Houston*, legislative librarian and a member of the University of Toronto senate, and by two members of the legislature, John Morison Gibson* and Richard Harcourt*, both of whom were also members of the university’s senate. On 5 March 1884 the legislature approved a motion that provision be made for the admission of women to University College. Wilson attempted to overturn this decision by publishing on 12 March an open letter to the minister of education, George William Ross*. Wilson declared himself in favour of the higher education of women and pointed out that in 1869 he had helped found the Toronto Ladies’ Educational Association in which, until its dissolution in 1877, he had given virtually the same lectures to large groups of women that he had delivered to men at University College. He believed, however, that mixing young men and women in their most excitable years would only distract their attention from their studies. Wilson preferred the establishment of a college for women in Toronto modelled on Vassar or Smith in the United States. For Wilson coeducation was simply a cheaper and inferior alternative to these models. He later admitted privately that lecturing on Shakespeare to young men in the presence of young women would be a trying ordeal because of the sexual allusions in some of the plays.

Wilson had great faith in the powers of passive resistance and he informed the premier, Oliver Mowat*, that he would do nothing unless forced to act by an order in council. Though Ross had assured him that the government would back up its commitment with additional financial support and give the college adequate time to make adjustments, an order in council on 2 Oct. 1884, one day after the start of classes, compelled him to admit female students. To Wilson this action was not only a personal betrayal but another instance of the politicians caving in to pressure.

As the result of such experiences as these Wilson developed a hypersensitivity to even the most trivial matters as potential points of criticism or political trouble. When he learned that someone had made measurements for a five-foot-high mirror for the female students’ toilet-room he protested to the minister that it was not necessary (an ordinary mirror was sufficient for brushing hair and adjusting neckties) and might arouse unfriendly comment. In June 1886 Wilson prevented the trade union leader Alfred F. Jury* from speaking at the Political Science Club because he loathed the “communist” and “infidel” and feared that by providing a platform for the controversial figure to address students the university would invite criticism, most likely from Methodists. He constantly fretted about other opportunities for politicians to meddle in the university, and much of his surviving official correspondence with Ross is devoted to defending professors’ long summer holidays and instructing the minister on such matters as the evil effects of political appointments.

Wilson’s last years as president were hardly uneventful. On the evening of 14 Feb. 1890 fire gutted the eastern half of the University College building, destroying the library and all of Wilson’s lecture notes. In addition to dealing with restoration and reconstruction, Wilson, haunted by the spectre of total blindness from cataracts, began to rewrite his notes. During his years as a university administrator Wilson made repeated visits to Edinburgh, wrote a warm memoir of publisher William Nelson, who had helped him in the days when he had tried to make a living as a writer, and kept abreast of the activities of the Society of Antiquaries. He also closely followed developments in North American Indian ethnology and prehistory. Usually away from the university from mid July to mid September, Wilson spent many summers with his daughter Jane (Janie) Sybil sketching and executing water-colours of the natural scenery in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Upon his death he left her an estate valued in excess of $76,000, over half of which was in the form of bank shares and debentures. Following her father’s instructions, she destroyed his papers except for a diary.

Aside from the astonishing diversity of his intellectual interests, the most arresting feature of Wilson’s temperament was a romantic, poetic streak that rejoiced in ancient ruins, valued the sheer variety of cultures, and emphasized the mysterious and unknowable elements in life. Raised as a Baptist, Wilson became an Anglican evangelical; in Toronto he supported the Church of England Evangelical Association, which campaigned against ritualism, and he was one of the founders in 1877 of the Protestant Episcopal Divinity School (later Wycliffe College). He was involved in the Young Men’s Christian Association in Toronto, serving as president from 1865 to 1870, and was instrumental in establishing a Newsboys’ Lodging and Industrial Home for young street urchins, giving public lectures to raise funds to maintain it.

There was a combative element in Wilson’s character. His biographer, Hugh Hornby Langton*, who knew him well in his last years, judged that Wilson was of “an irascible disposition” but that he had learned to control his temper in public. Certainly his journal and his many letters to his friend Sir John William Dawson, principal of McGill University, bear witness to a character that did not easily suffer fools, particularly if they were clerics or politicians. In the privacy of his journal he usually referred to his political opponents in the university as “Moloch” or “the snake” and he was utterly contemptuous of politicians in general. This was one reason why he at first declined (but later accepted) a knighthood at the rank of knight bachelor, which the government of Sir John A. Macdonald announced in June 1888: since politicians were honoured with higher orders of knighthood, Wilson regarded his own as a slight to all men of letters and science. He passed acerbic judgements on the latter too. When he was requested to advise the Marquess of Lorne [Campbell*] on nominations for the Royal Society of Canada (of which he became a charter member in 1882 and president in 1885), he told Dawson he considered the whole idea premature. Although he admitted that the scientific sections of the society might do creditable work, the section on English literature and history appeared ridiculous. Wilson had written encouraging reviews of Canadian poetry in the 1850s but 30 years later he felt that, apart from Goldwin Smith*, all the prospective candidates in the men of letters category were mediocrities. “As for this Canadian Academy,” he exploded, “call it the A.S.S. or noble order of nobodies.”

Time has played strange tricks with the reputation of this self-taught, eclectic polymath. Wilson has been remembered in Britain as a man of science and letters and as a radical pioneer in Scottish prehistory, but in Canada his career as a university statesman who fought against denominational control and political interference was judged most important, while his scholarship in history, anthropology, and ethnology was treated as incidental. Thus, mainly through Langton’s biography, Wilson became primarily a university figure – indeed, the tall, spare, erect old man with a luxuriant white beard was a local character. After 1960 both historians interested in the impact of Darwin in Canada and anthropologists concerned with the indigenous roots of their discipline paid far more serious attention to his scientific writings which can no longer be dismissed as the dabblings of a dilettante.

In addition to the works cited in the text, Sir Daniel Wilson is the author of Spring wildflowers (London, 1875); Coeducation: a letter to the Hon. G. W. Ross, M.P.P., minister of education (Toronto, 1884); William Nelson: a memoir (Edinburgh, 1889); and The right hand: left-handedness (London and New York, 1891). Other writings are listed in B. E. McCardle, “The life and anthropological works of Daniel Wilson (1816–1892)” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1980), 173–91.

An oil portrait of Wilson, painted by Sir George Reid in 1891, hangs in the National Gallery of Scotland (Edinburgh), and is reproduced in H. H. Langton, Sir Daniel Wilson: a memoir (Toronto, 1929).

AO, RG 2, D–7, 14; RG 22, ser.155. McGill Univ. Arch., MG 1022. MTRL, Sir Daniel Wilson scrapbooks. UTA, B65-0014/003-004. Doc. hist. of education in U.C. (Hodgins), vol.15. The university question: the statements of John Langton, esq., M.A., vice-chancellor of the University of Toronto, and Professor Daniel Wilson, LL.D., of University College; with notes and extracts from the committee of the Legislative Assembly on the university (Toronto, 1860). J. A. Wilson, Memoir of George Wilson, Regius professor of technology in the University of Edinburgh and director of the Industrial Museum of Scotland, by his sister (new condensed ed., London and Cambridge, Eng., 1866). Marinell Ash, “‘A fine, genial, hearty band’: David Laing, Daniel Wilson and Scottish archaeology,” The Scottish antiquarian tradition: essays to mark the bicentenary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and its museum, 1780–1980, ed. A. S. Bell (Edinburgh, 1982), 86–113. I. G. Avrith, “Science at the margins: the British Association and the foundations of Canadian anthropology, 1884–1910” (phd thesis, Univ. of Pa., Philadelphia, 1986). W. M. E. Cooke, W. H. Coverdale Collection of Canadiana: paintings, water-colours and drawings (Manoir Richelieu collection) (Ottawa, 1983). Annemarie De Waal Malefijt, Images of man: a history of anthropological thought (New York, 1974). A. B. McKillop, A disciplined intelligence: critical inquiry and Canadian thought in the Victorian era (Montreal, 1979). W. R. Stanton, The leopard’s spots: scientific attitudes toward race in America, 1815–59 (Chicago, [1960]). G. W. Stocking, Victorian anthropology (New York and London, 1987). W. S. Wallace, A history of the University of Toronto, 1827–1927 (Toronto, 1927). Douglas Cole, “The origins of Canadian anthropology, 1850–1910,” Journal of Canadian Studies, 8 (1973), no.1: 33–45. A. B. McKillop, “The research ideal and the University of Toronto, 1870–1906,” RSC Trans., 4th ser., 20 (1982), sect.ii: 253–74.

Carl Berger, “WILSON, Sir DANIEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wilson_daniel_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wilson_daniel_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carl Berger |

| Title of Article: | WILSON, Sir DANIEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |