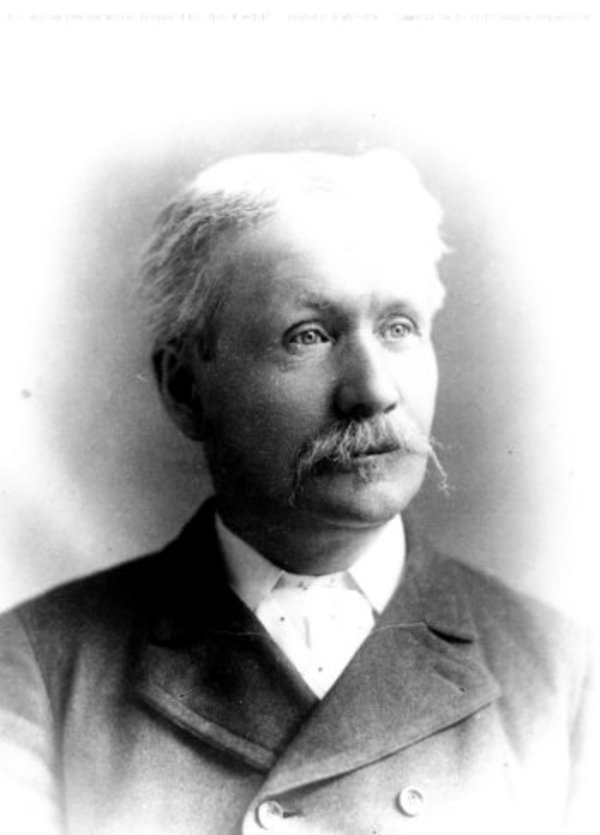

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SEMLIN, CHARLES AUGUSTUS, teacher, miner, packer, hotel owner, rancher, politician, and school trustee; b. 4 Dec. 1836 near Barrie, Upper Canada, son of David Semlin and Susannah Stafford; d. unmarried 2 Nov. 1927 in Cache Creek, B.C.

Charles Semlin was educated at a public school and by private tuition in Barrie; he subsequently became a teacher there. News of the Cariboo gold rush in British Columbia led him to give up his career in central Canada. He travelled to the Pacific coast, arriving in Victoria on 12 June 1862. His career as a miner was neither particularly long nor particularly successful. He prospected and mined for three summers in the Cariboo and then became a packer, carrying supplies between Lillooet and Quesnel.

In the spring of 1865 – evidently en route to the Big Bend of the Columbia River, which at the time was experiencing a gold rush of its own – Semlin came to Cache Creek. It would remain his home for the rest of his life. He soon found work in the area at Ashcroft Manor, managing the roadhouse and adjacent ranch of Clement Francis Cornwall and his brother Henry. Several months later he and a partner, Philip Parke, purchased a roadhouse of their own, Bonaparte House. Their advertisements stressed its strategic location at the junction of the wagon roads north to the Cariboo and east to Savona’s Ferry (Savona) and the upper Thompson River. Parke sold out his interest to Wilson Henry Sanford in 1868 and in 1870 Semlin took over Sanford’s share. Semlin traded the hotel to James Campbell in 1870, exchanging it for ranch land. He had been acquiring land in the area since 1867 through pre-emption and purchase. He gradually consolidated his holdings into one of the largest ranches in the region, which he would operate as the Dominion Ranch until his death in 1927.

Although Semlin became a successful rancher – the Dominion Ranch carried 15,000 head of cattle and was one of the most notable of the large interior ranches – he also engaged in many activities typical of early European settlers. He was the first postmaster in Cache Creek, for example. In 1873 he successfully lobbied the government for a public boarding school in the interior, so that the region’s scattered population of school-age children could receive formal education. As an mla, he introduced the legislation of 1874 that led to the establishment of the school in Cache Creek and he oversaw its official opening in June.

During its 16-year existence the Central Boarding School attracted a good deal of controversy [see John Jessop*]. The choice of Cache Creek over the larger community of Kamloops, the actions of the appointed school board (which comprised Semlin, Parke, Campbell, and C. F. Cornwall), and the conditions at the school all drew critical comment in the press. Semlin staunchly defended the institution, at one point even briefly assuming teaching duties there. It finally shut down in 1890. When a rural school district was created for Cache Creek several years later, Semlin, Parke, and Campbell all served as trustees.

Semlin’s career as a politician had begun in 1871, when he was elected in Yale to the inaugural session of the provincial legislature following British Columbia’s entry into confederation that year. His election was fortuitous. He and another candidate having tied for third place in the three-member riding, the returning officer allegedly put their names in a hat and declared Semlin elected when his name was drawn. His first years as a politician were not especially notable. He ran unsuccessfully in Yale in the general elections of 1875 and 1878. Then his fortunes improved; he was returned in 1882 and would retain his seat in the general elections of 1886, 1890, 1894, and 1898. He became leader of the opposition after the election of 1894, largely in consequence of Robert Beaven*’s failure to win re-election.

Even sympathetic newspapers noted that Semlin was not particularly effective as leader of the opposition. An affable and easy-going person, he appears to have been uncomfortable in the divisive atmosphere and raucous debate that characterized the legislative sessions of the late 1890s. Complicating matters was the fact that provincial politicians had not yet embraced the party allegiances of the federal arena; for example, both he and Premier John Herbert Turner were staunch Conservatives. Semlin was really only the titular head of the opposition, since the oppositionists represented all shades of the political spectrum. They were united in their discontent with the Turner government, a fragile base on which to build an effective political force.

By 1897 the land and railway policies of the Turner administration, as well as the actions of individual cabinet ministers such as Charles Edward Pooley and James Baker, were attracting considerable criticism in the national and provincial press. Semlin issued an official opposition platform that summer on behalf of the Provincial party, calling for an electoral redistribution to correct the over-representation of Vancouver Island and the under-representation of the mainland in the assembly, as well as for a reorganization of the civil service, constraints on Asian immigration, and government control of railways. In October 1897 the first gathering of provincial Liberals formulated a similar platform on which to oppose the Turner government. Although the Liberals split over the issue of introducing party lines in the next provincial election, the arrival earlier that year of prominent Manitoba Liberal Joseph Martin had served to give them greater presence.

The Turner government failed to win a clear majority in the election of July 1898, and contested results and delayed polling meant that the exact standings remained in doubt for some time. In a controversial move, Lieutenant Governor Thomas Robert McInnes dismissed Turner and his ministers in early August. He then turned to Beaven and asked him to form a ministry, in spite of the fact that the former premier had failed to win a seat. Beaven was unable to find sufficient support and so McInnes next called on Semlin. Semlin succeeded where Beaven had failed, although Martin had at first been reluctant to serve under him, likely because he hoped to be named leader at a Liberal convention planned for two weeks later in Vancouver. He would then have been well placed to claim the premiership for himself.

Semlin was premier of British Columbia for just 18 months, from 15 Aug. 1898 to 27 Feb. 1900. As many contemporaries later recalled, it was a tempestuous period, in part because of the loose affiliations and informal structures that held political groups together. Uniting such diverse elements would have been a formidable challenge for the most accomplished politician, and Semlin was not a forceful leader. His difficulties also reflected divisions within his cabinet, which included fellow Conservative Francis Lovett Carter-Cotton* as minister of finance and the mercurial Martin as attorney general. The two men detested each other, an animosity that contributed to the disintegration of the government. Semlin’s efforts to initiate wide-ranging reforms compounded his problems. Moves such as legislating an eight-hour day for hardrock miners were angrily denounced by mine owners and led to a lengthy and bitter strike (June 1899–February 1900) in the Kootenays. Similarly, the many dismissals that accompanied efforts to purge the civil service of patronage appointments caused heated protests and further eroded government support.

A speech by Attorney General Martin ultimately led to the collapse of the Semlin government. On 20 June 1899, just after the Kootenay miners’ strike began, Martin addressed a banquet in Rossland. Irate mine owners in attendance began to heckle. The speech deteriorated into a shouting match and ended in a brawl which had to be broken up by the police. Semlin demanded Martin’s resignation, which he tendered only after the caucus had sided with the premier.

When the next legislative session began in January 1900, Martin sat with the opposition. Semlin had not enjoyed a comfortable majority even with Martin in the cabinet; his departure called the government’s survival into question. The fatal blow came with the defeat at the end of February of a major government bill concerning electoral redistribution. When Semlin advised Lieutenant Governor McInnes of the defeat, he requested time to see if he could regain the confidence of the house. After several days of negotiations, he found several opposition figures willing to join his ministry. McInnes ignored this development and dismissed the government, calling on Martin to form a ministry. The lieutenant governor’s decision created an uproar in the assembly, which responded by passing a motion of no-confidence in Martin. The political situation in British Columbia was degenerating into chaos. Martin could not govern without a popular mandate, which he failed to win in the provincial election of June 1900. McInnes then turned to James Dunsmuir* to form an administration.

Semlin, who had represented Yale since British Columbia entered confederation, did not stand for election in 1900. He later commented that “I felt that I had done my share, and that it was time that younger shoulders were taking up the burdens of public life.” He returned briefly to politics, winning a by-election early in 1903, but he opted not to run in the provincial election held that autumn. He campaigned once more, in 1907, but was unsuccessful.

Throughout his time as a politician Semlin had remained active in his community. He was said to have helped to form a local agricultural association in 1888, probably the Inland Agricultural Society of British Columbia of which he was elected president in 1889. He participated in the establishment of the British Columbia Cattlemen’s Association in 1889 and he continued to play a role as the ranching industry faced a series of challenges, including greater competition from ranches in neighbouring Alberta, the formation and proliferation of company-owned ranches, and growing numbers of sheep in the area. Semlin followed other pursuits as well. His interest in Canadian history was well known and he served as president of the Yale and Lillooet Pioneer Society for many years. A good speaker, he was often asked to chair meetings or act as master of ceremonies, a role he continued to fill until well into his eighties.

Although known as a lifelong bachelor – even his death certificate lists him as single – Semlin raised a daughter, Mary, and left much of his estate, valued at just over $50,000 and consisting mainly of stock in the Dominion Ranch Limited, to his grandchildren. One account of his life, written after his death by a friend, states that he had adopted the girl. This appears to be contradicted by the census records of 1881, which list Mary’s mother, Caroline Williams, a native woman, as living with Semlin and using his surname, but which do not describe them as married.

When Semlin died in 1927, the Vancouver Daily Province carried the news on its front page, noting that he was the last surviving member of the province’s first legislature. Its editorial columns reflected on this fact, pointing out that Semlin’s adult life had spanned the history of the province of British Columbia since its formal creation in 1871. In his own community the local newspaper observed that his grave was next to a cenotaph commemorating European pioneers, “of which the deceased was one of the most beloved.”

BCA, E/C/Se5, 1879-90, 1896-1904; E/D/Se5, 1901-14; GR-1952, file 1928/2; MS-0700. LAC, RG 14, Parl., E-1, vol.1989, 5th session, 8th Parl., Addresses: For copies of all correspondence between the premier, secretary of state, and the lieutenant-governor of British Columbia, having reference to the dismissal of premiers Turner and Semlin. Univ. of B.C. Library, Rare Books and Special Coll. (Vancouver), Charles Semlin fonds. British Columbian (New Westminster), 22 Sept. 1866. R. E. Gosnell, “Prime ministers of B.C., 11: Hon. C. A. Semlin,” Vancouver Daily Province, 23 May 1921: 18-19. Mining Review (Rossland, B.C.), 24 April 1897. Vancouver Daily Province, 3, 11, 13 Nov. 1927. J. D. Belshaw, “Provincial politics, 1871-1916,” in The Pacific province: a history of British Columbia, ed. H. J. M. Johnston (Vancouver and Toronto, 1996), 134-64. Brian Belton, Bittersweet oasis: a history of Ashcroft; the first 100 years (Ashcroft, B.C., 1986). John Calam, “An historical survey of boarding schools and public school dormitories in Canada” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., 1962). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Edith Dobie, “Some aspects of party history in British Columbia, 1871-1903,” Pacific Hist. Rev. (Berkeley and Los Angeles, Calif.), 1 (1932): 235-51. Electoral hist. of B.C. S. W. Jackman, Portraits of the premiers: an informal history of British Columbia (Sydney, B.C., 1969). F. H. Johnson, John Jessop: goldseeker and educator; founder of the British Columbia school system (Vancouver, 1971). J. B. Kerr, Biographical dictionary of well-known British Columbians, with a historical sketch (Vancouver, 1890). E. B. Mercer, “Political groups in British Columbia, 1883-1898” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., 1937). W. [R.] Norton, “Cache Creek: the provincial boarding school, 1874-1890,” in Reflections: Thompson valley histories, ed. W. [R.] Norton and Wilf Schmidt (Kamloops, B.C., 1994), 26-35. B. C. Patenaude, Golden nuggets: roadhouse portraits along the Cariboo’s gold rush trail (Surrey, B.C., 1998); Trails to gold (Victoria, 1995). W. N. Sage, “Federal parties and provincial groups in British Columbia, 1871-1903,” British Columbia Hist. Quarterly (Victoria), 12 (1948): 151-69. J. T. Saywell, “The McInnes incident in British Columbia (1897-1900), together with a brief survey of the lieutenant-governor’s constitutional position in the Dominion of Canada” (ba graduating essay, Univ. of B.C., 1950). E. O. S. Scholefield and F. W. Howay, British Columbia from the earliest times to the present (4v., Vancouver, 1914), 4. G. F. G. Stanley, “A ’constitutional crisis’ in British Columbia,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science (Toronto), 21 (1955): 281-92.

Jeremy Mouat, “SEMLIN, CHARLES AUGUSTUS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/semlin_charles_augustus_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/semlin_charles_augustus_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jeremy Mouat |

| Title of Article: | SEMLIN, CHARLES AUGUSTUS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |