Source: Link

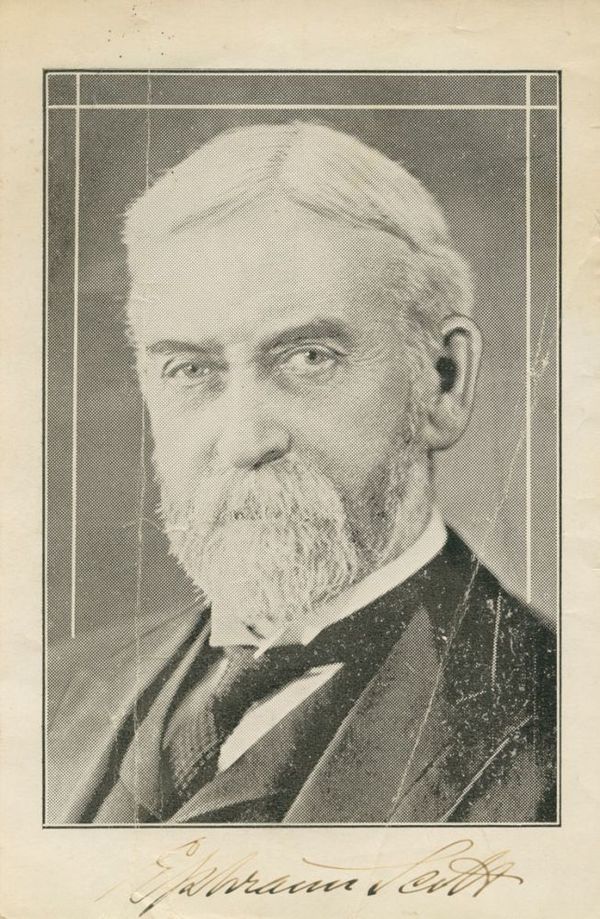

SCOTT, EPHRAIM, teacher, Presbyterian minister, journalist, and editor; b. 29 Jan. 1845 in East Gore, N.S., eldest child of James Alexander Scott and Ann Grant; m. first 4 April 1876 Margaret Ann McKeen (d. 1884), in Gays River, N.S., and they had three sons; m. secondly 5 Feb. 1891 Annie Roy (d. 1928) in Dartmouth, N.S.; there were no children of the second marriage; d. 7 Aug. 1931 in Montreal.

Ephraim Scott was born and raised in the bosom of the evangelical Presbyterian Church of Nova Scotia. His father was an elder and a pillar of the church in a Scottish immigrant community where there had been a Presbyterian house of worship since the 1790s. His first name, Ephraim, which had not been given to other family members, is freighted with theological symbolism in the light of his subsequent history. Like the Old Testament Ephraim, Scott unexpectedly inherited the birthright, as he would discover in 1925. Conservative evangelicalism and anti-establishmentarianism (in the tradition of Robert Burns*) were to define his 56 years as a minister of the Gospel.

Scott’s path to the ministry was indirect. He began his working life in the shipyards of William Dawson Lawrence* in Maitland, Hants County. While there, he came under the influence of the local Presbyterian minister, John Currie, who encouraged him not only to join the church but also to become active in it. The chief obstacle to Scott’s ordination, which soon became his goal, was his lack of secondary education, which he remedied by studying privately. After receiving a teacher’s licence about 1865, he taught in East Gore.

In 1868, in pursuit of his ultimate ambition, Scott registered at Dalhousie University in Halifax. During his undergraduate years he became a candidate for the ministry, spending his summers as a student missionary. After graduating ba in 1872, he remained in the city and enrolled in the Theological Hall of the Presbyterian Church of the Lower Provinces of British North America, where his mentor Currie was a professor. Although Scott did not complete the course, by 1880 he would be a member of the board of management of the hall’s successor, the Presbyterian College, which, in 1905, granted him an honorary dd.

A windfall of unknown origin (probably a legacy) enabled Scott to spend 1874 and part of 1875 on a grand tour of the Holy Land and the Mediterranean. He concluded this overseas sojourn in Scotland, where he attended lectures at the theological halls of the United Presbyterian Church and the Free Church, the Scottish equivalents of the united church to which he belonged. On his return to Nova Scotia in May 1875 he was licensed to preach by the Presbytery of Halifax. In July he received what the Presbyterian Witness (Halifax) described as a “unanimous and enthusiastic call” to Milford and Gays River, a dispersed rural pastoral charge; he was ordained and inducted in September. In June of the same year the Presbyterian Church in Canada had come into existence [see John Cook*; William Snodgrass*]; Scott’s efforts, decades later, to prevent its disruption would be the defining moment in his life.

In September 1878 Scott moved to New Glasgow to become the second minister to serve members of United Presbyterian Church. New Glasgow was to be his true home in many ways. He lies buried there, as do his wives and children, and his legacy endured years after his departure. He was an effective pastor; a census of worshippers conducted one Sunday in November 1888 found fully one-third of New Glasgow’s 1,900 Presbyterians at United Church. He was also a social liberal, a tendency in keeping with his theological education but a far cry from the stance that gave him his later reputation. In 1886, when women had no status in the church except as professed members or adherents and as foreign missionaries, he had boldly suggested to the synod that the unmarried daughter of the late Reverend Peter Gordon MacGregor succeed her father – for whom she had been acting – as church agent (synod treasurer); the proposal fell on deaf ears. During Scott’s pastorate United became the first congregation of the Presbyterian Church in Canada to adopt the system of weekly offerings, which superseded annual subscriptions or pew rentals.

In 1881 Scott founded the monthly magazine Maritime Presbyterian (New Glasgow) as a complement to the weekly newspaper the Presbyterian Witness, the official organ of the Synod of the Maritime Provinces. In 1886 he added a second publication, the Children’s Record, a monthly for youth which he would edit until December 1899. Both these periodicals were chiefly concerned with foreign missions, a subject dear to his heart. By 1891 he was joint convener of the General Assembly’s Foreign Missions Committee; he would serve as a member for 48 consecutive years. That year he succeeded James Croil* as editor of the Presbyterian Record (Montreal), the official voice of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, and he discontinued the Maritime Presbyterian.

After his move to Montreal Scott managed the Record for 35 years and never held a pastorate again. During his editorship his annual “Letters from assembly” became a familiar account of the General Assembly’s proceedings. As a journalist and commentator he was indefatigable; his writing was lean, lucid, and a pleasure to read. When he was not editing, he was sending letters to his counterparts at mainstream and religious newspapers, an activity which became more pronounced as he grew older and his indifference to, and scepticism about, the plan for Presbyterian union with the Methodists and Congregationalists [see Samuel Dwight Chown; Clarence Dunlop Mackinnon] developed into opposition and determined resistance.

Part ideologue and part demagogue, Scott gave neither political nor intellectual leadership to the resistance to church union in Canada, but he was far and away its most effective propagandist and polemicist. One of six ministers appointed to the General Assembly’s union committee in 1912 to represent those opposed to the project, he came to demonize union as an invention not of enlightened Protestants but of the parliament of Canada. He viewed the means deployed to achieve union as a breach of the constitutional liberty for which Presbyterian dissenters in Scotland had fought so hard and sacrificed so much. During what historian John Sargent Moir called the “long crisis of church union,” Scott and Robert Campbell* were among the few opposed to the project who retained senior offices in the church’s administration.

Scott’s position as editor of the Presbyterian Record was exceedingly delicate. Answerable as he was directly to the General Assembly, he kept his position only because the unionist majority did not wish to antagonize further the opposition by making an example of so eminent a resister. Scott had no hesitation in stating his own views and gave ample space in the Record to those who expressed similar opinions, but he was careful to adhere to the church’s official line when he had to.

In June 1922, when rapprochement between unionists and non-unionists still seemed possible, Scott stood unsuccessfully for moderator of the General Assembly. From his standpoint matters went from bad to worse; resistance had increased so much that the General Assembly would not permit a third popular vote on church union. Even Scott’s home congregation, Erskine Church in Montreal, would go into the United Church of Canada. In June 1925 Scott, then aged 80, was elected moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Canada, consisting of those Presbyterians who had opted to continue outside the new organization. The church had lost most of its ministers, much of its property, and two-thirds of its membership. Nonetheless, it seemed fitting that Scott’s moderatorship should coincide with the church’s golden jubilee and his own as a minister. He began his installation address by reciting the words of the old Scottish hymn, “O God of Bethel,” signifying that the disrupted church of 1925 would be what the church formed in 1875 had not been – the product of a counter-reformation. In contrast, some of his colleagues, such as John Cook, had viewed the 1875 church as “too exclusively Scotch.”

Despite his age, Scott was far from being a mere figurehead. In 1925 he assumed the interim principalship of Knox College in Toronto and the Presbyterian College of Montreal; both were ultimately retained by the Presbyterian Church. In December 1926 he relinquished the editorship of the Record, from which office unionist commissioners of the assembly had tried unsuccessfully to oust him in June 1925. He devoted his five-year retirement to doing good works and to writing authoritatively, if somewhat simplistically, about what he called the “Twenty years’ conflict,” comparing church union in Canada with the non-intrusionist controversy in the Church of Scotland (1834–43), which had also resulted in disruption and schism. In Scott’s opinion, state interference in the affairs of the Presbyterian Church in Canada had upset the delicate balance of church–state relations and compromised religious liberty.

Towards the end of his long life Scott was a sad and lonely figure, having lost his second wife and all three of his children. He lived frugally in rooms at the central Young Men’s Christian Association in Montreal, remitting his annual $3,000 pension to the General Assembly’s emergency-relief fund for indigent ministers and their families. In his will he left $50,000 to provide permanent financing for this fund. Old-fashioned towards the end of his life, Scott seems remote from modern Canadian Presbyterians. His conservative evangelicalism was anathema to the younger generation of neo-conservative academic theologians in his own church [see Walter Williamson Bryden*]. Yet Scott is the founding father of today’s Presbyterian Church in Canada and a patron saint of the evangelical renewal within it.

Some personal papers of Ephraim Scott are preserved by his descendants. A partial transcript of his 1874 travel diary was published by his granddaughter: W. S. [Philips] Trutnau, Diary of Dr. Ephraim Scott (Winsen an der Luhe, [Germany], 1989). Scott is the author of: A sermon preached at Shubenacadie, February 11, 1877 ([Truro, N.S.?], 1877); The Presbyterian Church in Canada: its preservation and continuance ([Montreal, 1914]); Continuing the Presbyterian Church in Canada: letters to an inquirer ([Montreal, 1917]); “Church union” and the Presbyterian Church in Canada (Montreal, 1928). His extensive contributions to Presbyterian journalism have not been compiled.

NSA, “Nova Scotia hist. vital statistics,” Halifax County, 1891; Hants County, 1876: www.novascotiagenealogy.com (consulted 9 May 2012). Globe, 8 Aug. 1931. Presbyterian Witness (Halifax, etc.), 1875–1925. Children’s Record (New Glasgow, N.S., etc.), 1886–99. N. K. Clifford, The resistance to church union in Canada, 1904–1939 (Vancouver, 1985). J. V. Duncanson, Rawdon and Douglas: two Loyalist townships in Nova Scotia (Belleville, Ont., 1989). A. L. Farris, “The fathers of 1925,” in Enkindled by the word: essays on Presbyterianism in Canada, comp. Presbyterian Church in Can., Centennial committee (Toronto, 1966), 59–82. B. J. Fraser, Church, college, and clergy: a history of theological education at Knox College, Toronto, 1844–1994 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1995). H. R. Krygsman, “Freedom and grace: mainline Protestant thought in Canada, 1900–1960” (phd thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1997). Barry Mack, “From preaching to propaganda to marginalization: the lost centre of twentieth-century Presbyterianism,” in Aspects of the Canadian evangelical experience, ed. G. A. Rawlyk (Montreal and Kingston, 1997), 137–53. Maritime Presbyterian (New Glasgow), 1881–91. J. S. Moir, Enduring witness: a history of the Presbyterian Church in Canada (3rd ed., Burlington, Ont., 2004); “Presbyterian Record: echo or conscience of the church,” Presbyterian Record (Don Mills [Toronto]), 1 June 1996: 15–17; “‘Who pays the piper …’: Canadian Presbyterianism and church-state relations,” in The burning bush and a few acres of snow: the Presbyterian contribution to Canadian life and culture, ed. William Klempa (Ottawa, 1994), 67–81. Presbyterian Church in Can., General Assembly, Acts and proc. (Toronto), 1891–1932. Presbyterian Record (Montreal, etc.), 1892–1931. I. S. Rennie, “Conservatism in the Presbyterian Church in Canada in 1925 and beyond: an introductory exploration,” Canadian Soc. of Presbyterian Hist., Papers (Toronto), 1982: 29–59. Jack Schoeman, “Ephraim Scott and church union” (ma thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, 2000).

Barry Cahill, “SCOTT, EPHRAIM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_ephraim_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/scott_ephraim_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Barry Cahill |

| Title of Article: | SCOTT, EPHRAIM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |