Source: Link

SCHAACK, NICHOLAS JOHN, farm labourer and protester; b. 15 Nov. 1883 near Kranzburg (S. Dak.), son of John Schaack and Anna Schmidt, farmers; d. 18 Oct. 1935 in Regina.

There were seven boys and eight girls in Nick Schaack’s family; twelve children lived to adulthood. His parents, who were from Luxembourg, had married there and emigrated to the United States about 1870. They lived first in Minnesota before homesteading near Kranzburg. Nick was a member of the village’s Holy Rosary Roman Catholic Church and he probably finished grade eight in school. A man of medium build with glasses, he is identified on his death certificate as a widower, but a record of his marriage has yet to be found. Being widowed might explain why he moved to Saskatchewan in 1910. He is listed in the United States census for South Dakota for 1900, but not 1910.

In Canada, Schaack worked as a farmhand and then as a tractor operator. By the time of the Great Depression of the 1930s, he was living in the Prince Albert area of Saskatchewan and he spent time in one of the relief camps for the unemployed in Prince Albert National Park. Many of the men in these camps were transferred south to the Department of National Defence camp at Dundurn during the spring of 1935. As soon as word of a march on Ottawa by unemployed men from British Columbia reached the camp, some 200 men headed for Regina in the third week of June to become part of the On-to-Ottawa trek, the most significant protest movement of the depression. Nick Schaack, then 51, was among them.

He found himself in an extremely tense situation in Regina. When 1,000 striking relief-camp workers had clambered aboard freight trains in Vancouver without hindrance in early June, to take their demand for “work and wages” directly to Ottawa, few realized their trip would acquire a momentum and symbolism that went well beyond a simple regional movement. Many observers believed that the resolve of the men would melt away as they passed through the interior. But once the trek reached southern Alberta and rolled towards Saskatchewan, picking up recruits at every stop along the way, it had come to epitomize all that was wrong with the federal government’s handling of the single, homeless unemployed during the depression. Conservative prime minister Richard Bedford Bennett* decided to stop the trek in Regina, by force if necessary.

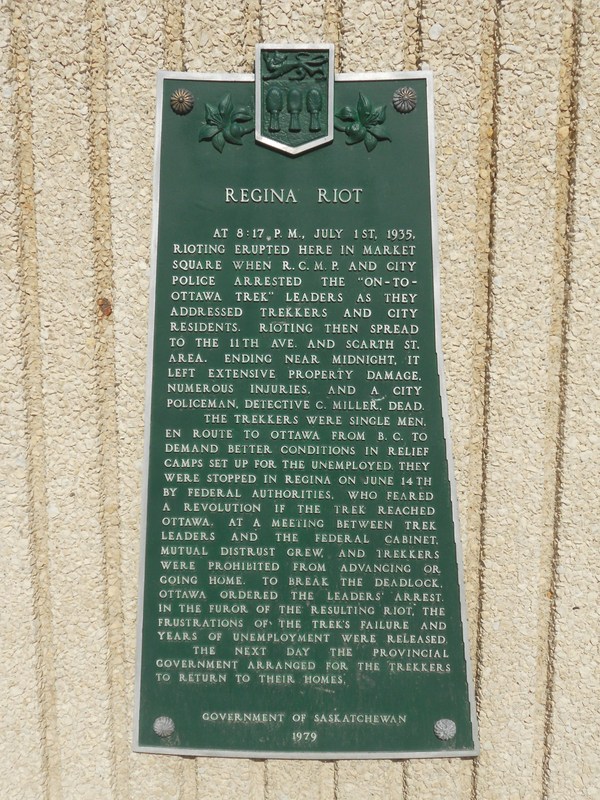

The trekkers reached the Saskatchewan capital on 14 June, and for the next two weeks, while a delegation led by Arthur Herbert (Slim) Evans* went on to Ottawa, they played a dangerous game of brinkmanship with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, each daring the other to make the first move. By the end of June, however, the men grudgingly conceded there was no way out of Regina because of police blockades, and after refusing federal terms for dispersal, they turned to the Saskatchewan government of James Garfield Gardiner* on the afternoon of 1 July for assistance in disbanding the trek. That evening, as the provincial cabinet met to discuss the request, the RCMP, with the support of the Regina City Police, executed warrants for the arrest of trek leaders at a public rally in Market Square. The raid quickly degenerated into a pitched battle between the police, the trekkers, and citizens that spilled over into the streets of downtown Regina, injuring hundreds and causing much damage.

Schaack was one of the rioters during the Dominion Day melee. He was forcibly subdued in a vacant lot and taken to the guardroom at the RCMP training depot. The next day he made a brief court appearance and was moved to the Regina jail, even though he was later remembered by a mounted policeman as having severe head injuries. He was committed to trial on 11 July, ten days after the riot. The only witness at his preliminary hearing was Constable John Timmerman, the Mountie who had made the arrest. He testified that he had found Schaack with a rock in each hand near the RCMP town station and had struck him across the shoulders with his riding crop.

Schaack’s bail hearing was scheduled for 18 July, but by then he was too ill to attend. His state might have gone unnoticed if not for the activity of a mothers’ committee, part of the Citizens’ Defence Committee established to help the imprisoned trekkers. It was during their first trip to the Regina jail on 14 August that the women learned Schaack was seriously ill. He had trouble eating and standing and spent his days confined to his cell bed. At the urging of the mothers’ committee, he was sent to the General Hospital on 25 August, the same day the charges against him were dropped. His condition worsened. He suffered a heart attack and then developed pneumonia. On 9 October the hospital superintendent wrote to Schaack’s family in South Dakota that he was unlikely to recover but that if he did, he would be transferred to the Weyburn mental hospital because of his head injury. He died nine days later. Since the family could not afford to bring his body back to South Dakota, he was quietly buried on the 21st in the Regina Cemetery.

Nick Schaack was the second fatality of the Regina clash, something that was denied at the time by police and government authorities. City detective Charles Millar had also died. The attempt to play down Schaack’s equally tragic death underscores the RCMP’s concern about their public image and reputation in the aftermath of the riot. After all, they were largely responsible for the turmoil and destruction because of their foolish insistence on wading into a volatile situation. But in the end the province’s Regina riot inquiry commission, chaired by Chief Justice James Thomas Brown, blamed the trekkers for the trouble while exonerating the RCMP. William Lyon Mackenzie King*’s new Liberal government in Ottawa subsequently maintained that its hands were tied, on unemployment and the trekkers, by the decisions of the Saskatchewan commission and the criminal courts. It was easier to let the riot and the deaths of Nick Schaack and Charles Millar be remembered as the legacy of the Bennett government.

The references for this article can be found in the author’s All hell can’t stop us: the On-to-Ottawa trek and Regina riot (Calgary, 2003). The 53 vols. of testimony before the Regina riot inquiry commission are held by SAB in Regina (F 415) and the transcript of Schaack’s preliminary hearing is on file with the Sask. justice dept. Lori Krei, née Schaack, of Waterton, S. Dak., kindly provided information about the family. Also useful is Victor Howard, “We were the salt of the earth!”: a narrative of the On-to-Ottawa trek and the Regina riot (Regina, 1985).

W. A. Waiser, “SCHAACK, NICHOLAS JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/schaack_nicholas_john_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/schaack_nicholas_john_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. A. Waiser |

| Title of Article: | SCHAACK, NICHOLAS JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2014 |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |