Source: Link

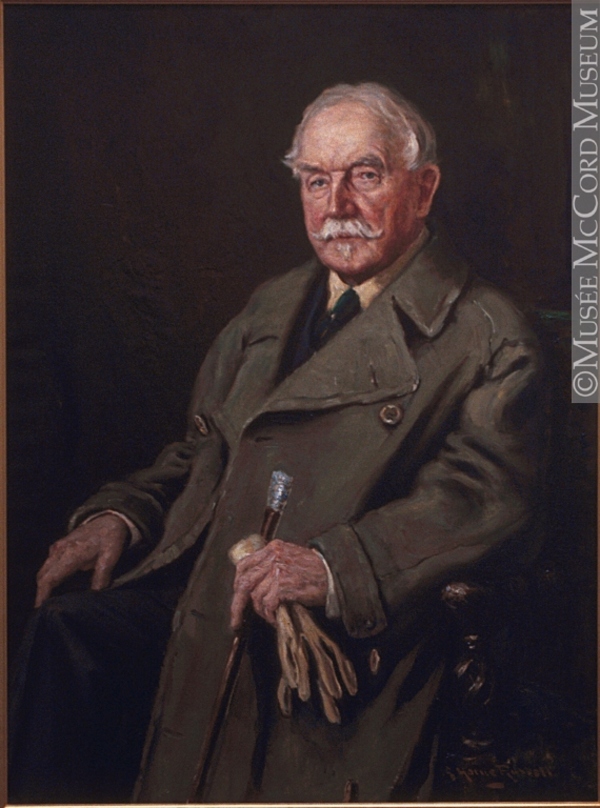

REED, HAYTER, militia officer, office holder, and businessman; b., probably on 26 May 1846, in L’Orignal, Upper Canada, son of George Decimus Reed and Harriet ———; m. first 6 June 1888 Georgina Adelaide Ponton (d. 23 Sept. 1889) in Belleville, Ont.; m. secondly 16 June 1894 Kate Lowrey, née Armour (d. September 1928), in Ottawa, and they had one son; d. 21 Dec. 1936 in Montreal.

Hayter Reed’s mother was Canadian; his father, who immigrated from Surrey, England, became a registrar in the village where his son was born. Hayter received his education in Toronto at Upper Canada College and then the Model Grammar School. Intent on being a soldier, he enrolled in the School of Military Instruction at Kingston, and graduated with a second-class certificate on 25 April 1865; on 28 September the certificate was upgraded to first class. Within two years he would be appointed drill instructor with the 14th Battalion Volunteer Militia Rifles, which he had joined on 15 June 1866. In 1871 he went with the provisional battalion in service in Manitoba to take up garrison duty at Fort Garry (Winnipeg) during the Fenian scare [see William Bernard O’Donoghue*]; by 1873 he was adjutant there. Meanwhile he undertook legal studies and was called to the Manitoba bar in 1872, although there is no evidence that he ever practised as a lawyer. After the disbanding of the battalion in 1877, Reed continued his military career on a part-time basis and also worked for the Department of the Interior as a land guide, assisting settlers in taking up their homesteads. He retired from the militia on 28 Oct. 1881 with the rank of major.

Reed’s long association with the federal Department of Indian Affairs began in 1881 when he was appointed Indian agent in Battleford, North-West Territories (Sask.). The natives under his charge, who were signatories to Treaty No.6, were in precarious circumstances due to the virtual disappearance of the buffalo, and were being pressured by the department to settle on the reserves assigned to them and take up agriculture. The new agent quickly acquired a low opinion of the Indians’ character, believing them to be chronic complainers who could only be reformed through the strict application of the department’s work-for-rations policy. He applied this policy with such harshness that the natives dubbed him “Iron Heart.”

Edgar Dewdney*, who was both lieutenant governor and Indian commissioner for the North-West Territories, was impressed with Reed’s abilities, and in April 1882 named him to the Council of the North-West Territories, a position he would hold until the council was superseded by an elected assembly in 1888. When Elliott Torrance Galt* resigned as assistant Indian commissioner on 15 March 1883, Dewdney boosted his colleague’s career yet again, selecting Reed to replace him; the appointment was made permanent on 5 May 1884.

As assistant commissioner, Reed was Dewdney’s right-hand man, spending much of his time travelling through the territories from his base first in Winnipeg and then in Regina, and quelling native resistance to government policy. During the spring of 1883, for instance, he was deployed to deal with the 3,000 Cree and Assiniboin who were gathered in the Cypress Hills area, where they hoped to obtain contiguous reserves [see Payipwat*]. His instructions were to persuade them to disperse and to settle instead on land in the Qu’Appelle, Battleford, and Fort Pitt districts; rations were withheld until they complied with this order. By his own account, it took three months of “hard labour” and “not a little risk of life” to accomplish the task.

When the North-West rebellion broke out in the spring of 1885, Reed toured the District of Saskatchewan, where the disturbances were concentrated, placating loyal but restless bands and urging them to remain on their reserves. The Métis resistance led by Louis Riel* collapsed in May, and in the uprising’s aftermath Reed’s knowledge of the country and its inhabitants was placed at the disposal of Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton*. His career was almost derailed during this period when he was accused of stealing furs belonging to a Métis named Charles Bremner. Although an 1890 inquiry into the looting would place the blame for the incident on Middleton, Reed’s reputation was tarnished by association.

Reed’s most enduring contribution to the post-rebellion era was his plan for the future management of the Indians. Presented to Dewdney in July 1885, the assistant commissioner’s proposal included the following recommendations, all of which were adopted by the government: disarmament of the Indians, abolition of tribal government, strict application of the work-for-rations policy, use of passes to restrict Indian mobility, denial of annuities to participants in the rebellion, dispersal of the band led by Big Bear [Mistahimaskwa*] for its role in the disturbances, and bestowal of conspicuous rewards on loyal natives. The requirement that Indians obtain a pass from the agent before leaving reserves had no legal justification and was a violation of treaty promises, but Reed championed the practice anyway. He convinced Dewdney and Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* that passes would prevent large gatherings where resistance to government policies might be fomented. The North-West Mounted Police were induced to cooperate in enforcing the rule. These tough measures were at the heart of the coercive system of administration that was imposed on western Indians in the 1880s and that would remain in force for several decades, and Reed was soon to play a role of greater significance in directing it.

On 3 July 1888 Dewdney resigned to enter the federal cabinet as minister of the interior and superintendent general of Indian affairs; one month later Reed succeeded him as commissioner, which made him the Indian department’s senior official in Manitoba and the North-West Territories. He brought the zeal and inflexibility of a military commander to the position and pushed forward with policies calculated to mould the Indians into peoples “imbued with the white man’s spirit and impregnated by his ideas.”

Reed believed that an industrial-school education offered the best means of culturally assimilating the younger generation of natives. There were ten of these schools on the prairies, managed by Christian missionary churches and financed largely by the federal government. The school program was divided evenly between academic and manual work. The half-day system, as it was called, appealed particularly to Reed: “Unless it is intended to train children to earn their bread by brain-work rather than by manual labour, at least half of their day should be devoted to acquiring skill in the latter.” To maximize the impact of the “civilizing” institutional routines, the students, who boarded at the schools, were not permitted to return home for holidays since “such return to their old associations … invariably interferes with the progress secured through uninterrupted residence in the schools.”

Although Reed was confident about the benefits of the department’s educational policy, there was much uncertainty and debate concerning the occupational destinies of those who finished school. It was expected that many graduates would return to their communities and apply their new skills and work habits for local development. Reed hoped that some would integrate into white society. To this end, during the 1890s students were hired out as farm labourers or domestic servants. Known as the outing system, this scheme was introduced in a number of schools with unimpressive results: participation was low, and the practice did little to assimilate native children into white society.

The vast majority of students ultimately returned to their reserves and some undoubtedly took with them skills that were useful in making a living. Their ability to do so, however, was seriously hindered by the Indian commissioner. In 1889 Reed initiated a policy of dividing reserves into allotments of 40 acres to which Indian males could be granted a “certificate of occupancy.” The idea was to promote individualism at the expense of the communal organization of Indian bands, but the scheme was also a prelude to imposing a particular approach to agriculture. Reed’s plan, which was based on the model of the self-sufficient peasant holding, required that Indian families raise a couple of acres of wheat and root crops, keep one or two cows, and conduct their operation entirely with simple hand tools. Native farmers, some of whom had already purchased the modern machinery whose use was now forbidden, were vehemently opposed to the new policy. Many department agents and inspectors objected too, and were dismayed to see crops lost because of the inefficiency of the peasant techniques. But Reed insisted that his orders be respected; he would not “pamper up the Indians in idleness” while machinery did the work.

The peasant-farming concept was partly a response to complaints from non-native farmers about market competition from their successful native counterparts. Under Reed’s policy, reserve agriculture would be removed from the mainstream economy and kept in a state of underdevelopment. As a further benefit to non-Indian farmers in the region, the switch to small holdings would free up “surplus” reserve land for sale to settlers. But more than addressing the infringement on the white farmers’ market, the program also reflected Reed’s belief in an evolutionary theory which held that Indians could not leap from savagery to civilization without duly progressing through the intermediate stage of barbarism.

Reed’s hard-line approach was deeply resented by natives. Yet his superiors in Ottawa approved: they were convinced that natives required strict control and coercive direction. Despite the trouble caused by the stolen-furs incident, Reed’s career was in the ascendant. Before departing Ottawa in the fall of 1892 to become British Columbia’s lieutenant governor, Dewdney had made arrangements with Thomas Mayne Daly*, the incoming minister, to force the retirement of Lawrence Vankoughnet, deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs, whom Dewdney disliked. On 2 Oct. 1893 Vankoughnet was superannuated and Reed moved into the department’s top position at Ottawa.

His tenure as department head, which lasted until February 1897, was brief and unremarkable. Legislative changes introduced during these years were aimed primarily at further strengthening the department’s authority to regulate or suppress Indian social and religious practices. An 1894 amendment to section 117 of the Indian Act extended the powers held by Indian agents, ex officio justices of the peace, allowing them to pursue offences against the Criminal Code as well as certain sections of the act. The following year saw the introduction of an amendment to section 114. Vigorously championed by Reed, the reworded legislation now defined the rites of native festivals that were forbidden, which rendered it more difficult for natives to evade the law, and made engaging in these rites an indictable offence. For Reed, not only did the “heathenish” festivals obstruct the efforts to assimilate and Christianize the natives, they also interfered with Reed’s policy regarding the Indians’ agricultural efforts.

During his years in Ottawa Reed’s personal life took a turn for the better. His first wife, Georgina Ponton, had died a year after their 1888 marriage, and on 16 June 1894 he married Kate Armour. A daughter of future chief justice of Ontario John Douglas Armour and widow of New York lawyer Grosvenor Porter Lowrey, she was a connoisseur of antiques and paintings, and collected shoes as a hobby. Brilliant, popular, and well connected socially, she counted among her friends Lady Aberdeen [Marjoribanks], the wife of the governor general. The Reeds’ marriage was a happy one and the couple had a son, Gordon, who was born in September 1895.

Reed’s advancement in the Indian service was partly owing to his membership in the Conservative Party and his friendship with Dewdney, a party luminary and a prominent dispenser of patronage. His future was therefore far from certain after the accession to power of Wilfrid Laurier*’s Liberals in 1896. The new minister of the interior, Clifford Sifton*, who was also superintendent general of Indian affairs, was determined to create openings for loyal supporters. In February 1897 he announced that the department would be reorganized into three branches, and offered Reed a choice: become head of a branch, or go on the retirement list. The first alternative would have meant a salary drop from $3,200 to $2,000 per year; he found the second more palatable and left the federal government on 31 March 1897.

The Toronto Globe, which had always been hostile to Reed, rejoiced at his downfall. Friends such as Sir William Cornelius Van Horne* were willing to assist, and Reed accepted the position of manager of the Château Frontenac, the Canadian Pacific Railway hotel in Quebec City. By 1905 Reed was manager-in-chief of the CPR’s hotel department. Van Horne, aware of Kate’s artistic knowledge, provided opportunities for her as well. Her genius for design was put to use transforming the company’s hotels from coast to coast, making them the “most home-like of any on the North American continent,” according to an article in the Manitoba Free Press.

After retirement the Reeds divided their time between their Montreal apartment and their cottage in St Andrews, N.B. Kate died in September 1928 and Hayter survived her until 21 Dec. 1936. His obituary in the Montreal Gazette described him as “a vigorous personality and widely known throughout the Dominion.”

Hayter Reed belonged to that enthusiastic breed of Protestant, English-speaking Ontarians who sought personal advancement on the western prairie frontier. Skilled with a gun and comfortable on horseback, he brought the discipline and inflexibility of military training to his work in the Department of Indian Affairs. He is best known for his leadership in shaping and implementing post-rebellion federal Indian policy. But it was a policy that conceived of no native role in a changing Canada, and that caused isolation, economic stagnation, and resentment.

Hayter Reed’s date of birth is usually given as 26 May 1849. Evidence from the 1851 census and military school records, however, indicates that he was likely born on 26 May 1846.

AO, RG 80-5-0-159, no.4824; RG 80-5-0-212, no.2366. LAC, R180-124-1; R180-126-5; R216-0-0; R4505-0-2; R5319-0-1; R7531-0-8; R7693-0-0; R8017-0-X; R10811-0-X; R14424-0-3; R14698-0-8; “1851 Census,” Prescott, Canada West [Ont.], dist.31, subdist.300: 47. Gazette (Montreal), 1936. Globe, 1897. Manitoba Free Press, 1913. Winnipeg Free Press, 1936. Can., Acts, 1894–95; House of Commons, Journals, 1890, app.1 (report of the select committee In re Charles Bremner’s furs); Parl., Sessional papers, 1891 (report of the Dept. of Indian Affairs, 1890). Sarah Carter, Lost harvests: prairie Indian reserve farmers and government policy (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1990). D. J. Hall, Clifford Sifton (2v., Vancouver and London, 1981–85), 1. Douglas Leighton, “A Victorian civil servant at work: Lawrence Vankoughnet and the Canadian Indian department, 1874–1893,” in As long as the sun shines and water flows, ed. I. A. L. Getty and A. S. Lussier (Vancouver, 1983), 104–19. Madge Macbeth, Over my shoulder (Toronto, 1953). Katherine Pettipas, Severing the ties that bind: government repression of indigenous religious ceremonies on the prairies (Winnipeg, 1994). G. F. G. Stanley, The birth of western Canada: a history of the Riel rebellions ([Toronto], 1960). L. H. Thomas, The struggle for responsible government in the North-West Territories, 1870–97 (2nd ed., Toronto, 1978). E. B. Titley, The frontier world of Edgar Dewdney (Vancouver, 1999); “Indian industrial schools in western Canada,” in Schools in the west: essays in Canadian educational history, ed. N. M. Sheehan et al. (Calgary, 1986), 133–53. J. L. Tobias, “Canada’s subjugation of the Plains Cree, 1879–1885,” CHR, 64 (1983): 519–48.

E. Brian Titley, “REED, HAYTER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/reed_hayter_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/reed_hayter_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | E. Brian Titley |

| Title of Article: | REED, HAYTER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2015 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |