Source: Link

QUERTIER, ÉDOUARD, Catholic priest, temperance advocate; b. 5 Sept. 1796 at Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu, L.C., the second of 17 children of Hélier Quertier, a sacristan, and Marie-Anne Ariail; d. 17 July 1872 at Saint-Denis-de-Kamouraska, Que.

Édouard Quertier studied at the seminary of Nicolet from 1809 to 1815, and in Abbé Paul-Loup Archambault’s words he was “the best in his class.” In 1815 he enrolled for theology at the seminary of Quebec, which he left three years later. In 1820 he was at Sainte-Marie-de-la-Nouvelle-Beauce, where he was working as a tutor. He then decided in favour of law and in 1822 went to work in Charles Panet’s office at Quebec. Two years later, being destitute, he was forced to abandon his legal training and asked to return to ecclesiastical life. Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis* decided to admit Quertier only after he had had two years for reflection; during this period the young man directed the parish school of Saint-Antoine at Rivière-du-Loup (Louiseville). Finally, on 9 Aug. 1829, on the threshold of his 34th year, Édouard Quertier was ordained priest at Quebec by Bishop Bernard-Claude Panet*.

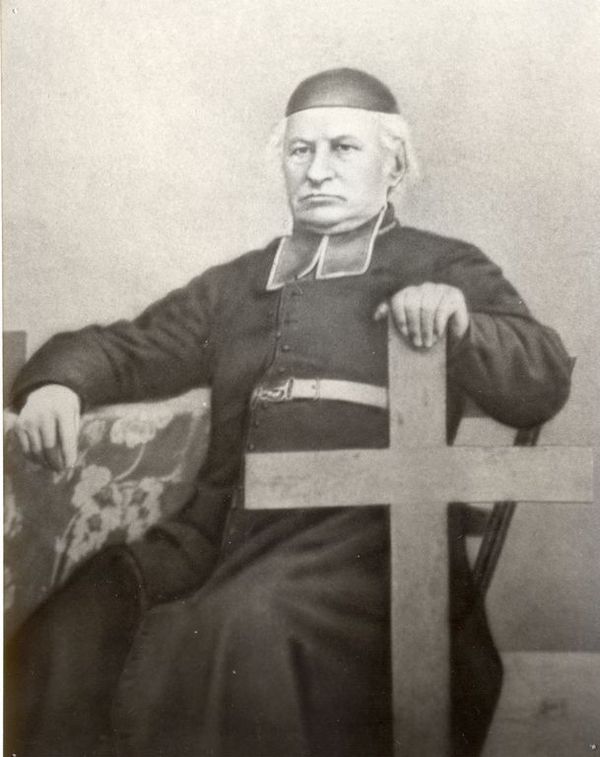

With “an athlete’s build, a rugged face, heavy and prominent features, an imperious look, hair flowing from under the black skull-cap,” Abbé Quertier was a remarkable man. In October 1831, after 26 months as a curate, he was appointed first resident parish priest of Saint-Antoine, on Île aux Grues (Montmagny County). “A charming little spot,” Quertier wrote. “An old hovel for a lodging, the only trouble being that as it had to be half repaired twice in three years, I had to retire to the attic of my little sacristry. If I was not able to build a presbytery, everyone knows who thwarted my endeavours at that time, and everyone also knows that for the sake of peace I gave in and withdrew.” The parish priest was in conflict with Abbé Charles-François Painchaud*, the owner of the site where the parish church and presbytery were built, who fiercely upheld his rights. “All the trouble . . . falls on the great benefactor of the island [Painchaud],” the parish priest wrote to Charles-Félix Cazeau*.

In the spring of 1833 Abbé Quertier visited the Mingan missions (Saguenay County); he returned to his island and lived there, grumbling the while, until 1834, when Bishop Joseph Signay* yielded to his complaints and appointed him parish priest of Saint-Georges de Cacouna. Would he be there “the angel of peace and the agent of reconciliation” that his bishop hoped for? At this period the civil and ecclesiastical powers were continually at variance. A bill designed to modify the composition of the parish council assemblies, by giving more representation to the important persons of the parish, had been presented to the Legislative Assembly during the session of 1831 and rejected by the Legislative Council; it had set the state against the church, at least in the minds of the public, by the stir it had created. Quertier was warned that at Cacouna he would be caught between two opposing groups: one in favour of building in the village itself a church intended to replace the old chapel, the other of building this new church in the country. “It is only a matter of softening and overcoming the prejudice of the people far removed from the place decided upon . . . [which is] so difficult, especially when one proceeds legally.” Quertier did partly satisfy his bishop’s expectations: after seven years as parish priest he had to his credit a new presbytery in the village and a renovated chapel.

As early as 1835, while he continued to assure Bishop Signay that “peace is made and almost solidly established,” the priest was seeking his recall. Every now and again, in pages of bitter claims and mocking insinuations, the prolific letter-writer renewed his pleas. Finally in 1841 he received a reply, but not to his liking. In September 1841, for the second time in 12 years of ministry, Abbé Quertier was called upon to set up a new parish, that of Saint-Denis-de-Kamouraska. “How did I accept this arid rock? . . . When I arrived [in October], there was not even a piece of board on which to place a bed or a table. I had to go down the slope and rent a small house, or rather a cabin. No matter! I waited there, until my lodging was acceptable.”

It was however from this isolated corner that Quertier’s fame was to spread. At Saint-Denis he was to realize the greatest achievement of his career, the founding of the Société de Tempérance, or Société de la Croix Noire. Since 1839 outstanding preachers, including Bishop Charles-Auguste-Marie-Joseph de Forbin-Janson* and Charles-Paschal-Télesphore Chiniquy*, had been protesting against the scourge of alcoholism. But it was Quertier who could claim the credit, in 1842, of drawing up the statutes of the temperance society, formulating the oaths of its new crusaders, and setting up as a symbol a bare black cross. The following year Quertier was able to write: “Temperance prevails everywhere. Each house is decorated with a blessed cross, the reminder of our undertakings.” In 1844, the same happy affirmation: “Everything is peaceful here. I can attribute only to our society of the cross our real tranquillity, in the midst of the discords of our neighbours. . . . This blessed cross . . . must speak with its mighty language.”

From 1847 on, Abbé Alexis Mailloux assisted Quertier. He came to be considered his most powerful collaborator, even his master. Gradually, through Quertier’s action, the preaching of total abstinence spread far beyond the confines of Saint-Denis and even of the diocese of Quebec. Quertier’s marvellous eloquence made him famous: in the pulpit he became in turn “the man of fire,” the passionate orator, the suave preacher or the learned catechist: “There were often more people at catechism than at mass . . . ,” noted the minister. “The church is often so crowded that one can barely get through.” Popular belief attributed miraculous virtue to the black cross, and the Quertier rosary was thought to have extinguished fires and cured sick people.

Although the priest’s memory is still revered, history must perforce acknowledge that the man was difficult: unstable and always fretful, violent by nature, given to finding fault with the neighbouring parish priests, and unreliable in his estimation of the politicians of the time. Quertier had his knuckles rapped many times by the heads of the diocese, and he made life hard for certain of his contemporaries, including the seigneur of La Bouteillerie, Pierre-Thomas Casgrain, the

After 15 years of parish ministry at Saint-Denis, Abbé Quertier, “old [and] worn out,” obtained his retirement, which was spent in calm and serenity. As his hair whitened, the violence of the man lessened, but the faith and zeal of the priest did not decline. He died in Saint-Denis and was buried under the sanctuary of the church. Today his statue looks down from the bare hill that he climbed more than 100 years ago.

AAQ, Cahier Signay, p.196; Registres des lettres des évêques de Québec, 15, f.295; 16, f.260; 19, f.252; Séminaire de Nicolet, I, 217, 238. Archives de l’évêché de Sainte-Anne (La Pocatière, Qué.), Isle aux Grues, I, 10; Saint-Denis, I, 66, 71, 82, 100. AJQ, Greffe d’Étienne Boudreault, 9 sept. 1822. Archives paroissiales de Saint-Denis (comté de Kamouraska, Qué.), Registre des baptêmes, mariages et sépultures, 1872. Archives paroissiales de Saint-Denis (comté de Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué.), Registre des baptêmes, mariages et sépultures, 1872. “Inventaire de la correspondance de Mgr Bernard-Claude Panet, archevêque de Québec,” Ivanhoë Caron, édit., APQ Rapport, 1934–35, 350. J.-B.-A. Allaire, Histoire de la paroisse de Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu (Canada) (Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué., 1905), 256. Julienne Barnard, Mémoires Chapais; documentation, correspondance, souvenirs (4v., Montreal et Paris, 1961–64), I, 191–237; II, 17–22, 36–39, 60, 191–92, 321–24, 346–49. N.-E. Dionne, Vie de C.-F. Painchaud; prêtre, curé, fondateur du collège Saint-Anne de la Pocatière (Quebec, 1894), 399–404. J.-A.-I. Douville, Histoire du collège-séminaire de Nicolet, 1803–1903, avec les listes complètes des directeurs, professeurs et élèves de l’institution (2v., Montreal, 1903). Inauguration du monument Quertier; quatrième croisade de tempérance (Quebec, Kamouraska, 1925).

Julienne Barnard, “QUERTIER, ÉDOUARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/quertier_edouard_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/quertier_edouard_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Julienne Barnard |

| Title of Article: | QUERTIER, ÉDOUARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |