Source: Link

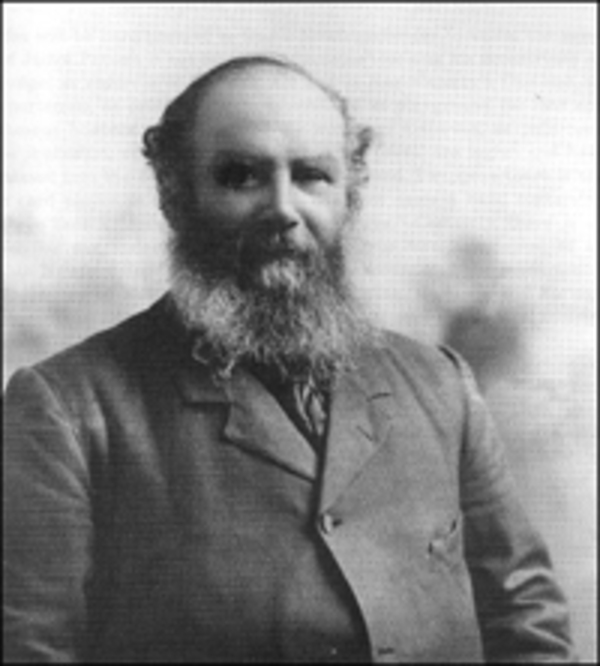

PROWSE, DANIEL WOODLEY, lawyer, politician, judge, historian, essayist, and office holder; b. 12 Sept. 1834 in Port de Grave, Nfld, fourth of the seven children of Robert Prowse and Jane Woodley; m. 13 July 1859 Sarah Anne Edleston Farrar in Sowerby, near Halifax, England, and they had three sons and three daughters; d. 27 Jan. 1914 in St John’s.

The Prowse family from which the inimitable judge and historian Daniel Woodley Prowse descended was of Devon origin, and the first member with a direct Newfoundland connection appears to have been Samuel Prowse of Torquay, a West Country trader, who married the eldest daughter of the Mudge family, also of Torquay and with old Newfoundland interests. Their son Robert came to the colony at the age of ten as an apprentice, married a daughter of Daniel Woodley of St Mary Church, Devon, and by the 1830s was in charge of the Conception Bay operations of the St John’s firm Brown, Hoyles and Company. The first four of their children were born in Port de Grave, a settlement of some 400 inhabitants. Acute economic conditions, not helped on occasion by sectarian divisions, created turbulence during these years, and in 1835 the Prowse house and premises were burnt to the ground, whereupon Robert moved with his family to St John’s. A versatile entrepreneur, he soon established under his name a firm that reached some prominence as a supplier to the Bank fishery and an exporter of fish, and in other ventures.

Daniel received his early education in St John’s at a private school run by a Miss Beenland and at the Church of England Academy. When he was 14, he was sent to the Collegiate School in Liverpool, England. He subsequently spent two years in Spain to study the language and the Newfoundland-Spanish fish trade with a view to entering his father’s business. His elder brother Robert Henry became the principal in the firm when, in 1856, their father retired to England with his wife and several of the younger children. Daniel meanwhile had begun the study of law and, like his almost exact contemporary Robert John Pinsent*, also a native of Port de Grave, he was articled to the accomplished lawyer and politician Bryan Robinson*, clearly a marked influence on him.

Prowse was called to the bar in 1858, and the following year he married Sarah Farrar, in accordance with the general principle he later formulated: “Marry first and get the . . . job after.” He purchased a substantial property on the outskirts of St John’s in 1860, erected a house, and developed gardens; with a pond, stream, and nearby snipe marshes, it was a setting appropriate for his recreations – “writing, shooting, fishing, gardening, natural history” – and the raising of children. From a marriage of uncommon affection, Prowse launched with gusto into the practice of law, politics, the justiciary, writing, and manifold public services.

A sociable creature, he had an irrepressible love of company, of talk and argument. He was an early secretary of the St John’s Athenæum (a subscribers’ club, library, lecture hall, and theatre) and a frequent lecturer. On one occasion at least “Messrs. Prowse and [William] Whiteford kept the audience in roars of laughter, the one in rendering some choice portions of Artemus Ward, the other with Comic Songs.” He seems to have known all his contemporaries, and the history of the colony he was to write is replete with a lifetime’s remembered talk, anecdote, and reminiscence of the small society he grew up in. His career as a barrister was successful without being spectacular. Like many of the legal profession, he ran for political office, first in the turbulent election of 1861, when he followed his brother Robert in Burgeo and La Poile and was elected for the Conservative party under Hugh William Hoyles*. After Hoyles resigned in favour of Frederic Bowker Terrington Carter* in 1865, Prowse was returned for the same district in the election that year. Those parts of his History of Newfoundland that deal with the events of these years contain vivid vignettes by a shrewd participant. He took part in debate: the Newfoundlander reported fourteen substantial speeches of his in 1866, nine in 1867, and six in 1868. Outside the legislature he was active among the supporters of confederation. In October 1867, for example, the Morning Chronicle commented, “‘A Daniel came to judgment’ in the person of D. W. Prowse, Esq., member for Burgeo and La Poile. He appeared that evening to support the views of his friend Mr. [Ambrose Shea*] . . . he made it the occasion of a grand prepared display of forensic eloquence.” A writer for the same journal on another occasion, however, observed of Prowse, “This young man’s information is more remarkable for its breadth than its depth.”

His legal career changed direction with his appointment in 1869 as a judge of circuit court (he would later sit on the Central District Court in St John’s). His duties involved those of stipendiary magistrate, police magistrate, and justice of the peace. These were mostly low-level judicial functions, yet close to the ordinary life of his time. On circuit he acquired unusual familiarity with the communities and people of the colony, his visitations notoriously prolonged when there was a coincident open season on wildfowl, fish, or deer. He brought to his profession, as to sport, energy and thoroughness.

Within eight years he had compiled his Manual for magistrates in Newfoundland . . . (1877), written to provide outport justices with clear instructions and forms for all their ordinary duties. Using earlier English writers on magisterial law, he produced a valuable work, condensed and in particular made applicable to the special circumstances and customs of Newfoundland. Known popularly as “Prowse’s manual,” it served two generations of magistrates and justices of the peace. For him the experience of travelling on circuit became a storehouse on which he would draw as an essayist. He learned to know his fellow-countrymen as few others of his time, or any time, have known them. His steady practice, in an era when the ancient truck system was still alive, of seeing that balances owing by a supplying merchant to a fisherman were paid in cash is particularly noteworthy. It was, he wrote towards the end of his life, “my great business at first,” and he quoted the remark he had heard one old fisherman make to another: “Prowse’s court is the only fair stand for law in the country. One word from the Judge and the merchant pays out the cash in a jiffy.”

Anecdotes cluster around Prowse, as they do around fellow judge James Gervé Conroy, from the beginning to the end of his career. There is, for example, from his early days as a judge the ritual farewell on a Monday morning, when the “Poet of Pokeham Path,” a St John’s balladeer whose custom it was to elevate his muse with spirituous beverages of a Saturday night, left the court with an impromptu verse:

Good morning to your worship,

Good morning to Judge Prowse,

I hope the little angels

Will hover round your house.

Prowse’s language both on and off the bench could be exuberant on occasion. In one instance three naval officers, convicted of violating the colony’s game laws, brought a suit against him in the Supreme Court, which, however, found that “an action for slander will not lie against a stipendiary Magistrate for words spoken in his capacity of magistrate.” One of the sentences specified in his Manual, “thirty days,” was remembered among contemporary players of whist, and in the 1920s and 1930s among St John’s poker players, in the expression “a Judge Prowse” for a hand of three tens.

In December 1897, on the eve of his retirement, Prowse would write a memorandum to Governor Sir Herbert Harley Murray* in support of a claim for knighthood. He listed his services: his restoration, as superintendent of police, of order to a turbulent capital; the quelling of disturbances in the fishing towns of Harbour Grace and Catalina following reports of the failure of Ridley and Sons in 1870 [see Thomas Ridley*]; the arrest of forgers of Commercial Bank notes and the recovery of the notes on the French island of Saint-Pierre in 1874; the restoration of order on the then unregulated frontier area of St George’s Bay in 1877; his firm handling of the riotous opposition by landowners to the construction of the railway on the Avalon peninsula. Next to his Manual and his History, Prowse gave pride of place to his nautical adventures in the late 1880s, when “at an hour’s notice I was sent off to Fortune Bay with two old tugs to carry out the Bait Act.” The act restricted the sale and export of bait fish taken in Newfoundland waters to the French cod fishery, and it was enforced by Prowse and his flotilla with an energy and enthusiasm that comes through even the characteristically cautious notation of Attorney General Sir James Spearman Winter on Prowse’s record. “I think he has somewhat overstated the value of his work, and in others he went a little outside of his proper sphere. . . . I can bear testimony to . . . the fearlessness of consequences which he has always shewn in what he believed to be the discharge of his duty.” But for Prowse his adventures as “Admiral of the Bait Squadron” marked “the turning-point in my life.” His plunge into a modern episode of the ancient rivalry between English and French in Newfoundland led him to study not only the legal and other aspects of the immediate confrontation, but also the long tale of a fishery which he saw as a major theme in the history of the colony itself. In the time his other duties allowed, he now immersed himself in the materials that came to hand or could be collected on a subject which would occupy him for seven years.

A hundred years after its appearance in 1895 Prowse’s History remains unchallenged, for the four centuries that it covers, as the best (some would say “unfortunately the best”) general history of Newfoundland. He had able predecessors: John Reeves*, Lewis Amadeus Anspach*, Charles Pedley*, and others whose interpretations of their common subject left their mark on his work. But what distinguishes Prowse’s ample study, considered as a work of its time, is not simply its scale but his uncommon use, as the title-page declares, of the “English, colonial, and foreign records.” His bibliography of the published sources used in writing the book stood for decades as the most comprehensive listing in print. His net was cast wider than the printed documents, however: uncalendared state papers, commercial, parish, and other local records on both sides of the Atlantic, and French, Spanish, and Portuguese sources were also drawn on. In gathering his primary material Prowse was assisted by his older sons, especially George Robert Farrar Prowse, an indefatigable worker in the British and European archives who helped to see the History through the press.

Prominent in the work is Prowse’s intention not only to describe how the colony grew but also to show the influence of its founding on England, and thus to avoid the frequent limitation of contemporary colonial writers, who looked at the world from the wrong end of a telescope. His work expands on that of James Anthony Froude on the rise of the first British empire, but with a clearer sense than Froude’s of the economic drive of the West Country–Newfoundland enterprise. Prowse was well read in the work of the great historians of his century, Lord Macaulay and Henry Hallam in Britain, for instance, but equally the Americans John Lothrop Motley, William Hickling Prescott, and Francis Parkman*. He knew and corresponded with his contemporary New England colleagues Justin Winsor, an authority on the voyages of Jacques Cartier*; Charles Levi Woodbury, an expert on the fisheries of the North Atlantic; and James Phinney Baxter, who studied the coeval overseas plantation of Maine. Among these readers the reception of Prowse’s work was immediate and warm.

The History appeared in June 1895, and it carried a graceful preface by the eminent man of letters Edmund Gosse, son of Philip Henry Gosse* and a lifelong friend of the judge. Edmund’s son Philip, in a memoir written half a century later, described his first visit to St John’s as a schoolboy that summer, and his being greeted by his host in a voice “famous throughout the Colony.” “Whenever the judge addressed any one more than a few feet distant, he bellowed in a voice such as the skipper of a fishing schooner might use when shouting to his crew in the teeth of a howling gale. This impression was strengthened by his appearance: burly and broad, with a big straggling beard. . . . His famous History of Newfoundland had just appeared, printed at his own expense, for the author held decided views on the honesty of publishers, booksellers and the trade generally.” Philip Gosse goes on to describe the judge as salesman – to the Newfoundland government three hundred copies at a pound each, to Robert Gillespie Reid*’s railway company one hundred copies. Wherever Prowse went, by train, by boat, or with horse and buggy, copies of his book went too, to be pressed upon all he encountered until, within a year, the first edition was exhausted and a second, without the huge apparatus of notes, appendices, indexes, and illustrations, took its place. (A photographic reprint of the 1895 volume, issued in 1972, and the salvaged text of a long-lost third edition from the judge’s hand, issued in 1971, have met a continuing demand for the work.)

By the time the History appeared, Prowse’s days on the bench were drawing to a close. His decisions as a judge, while seldom overturned on appeal, had not always been either uncontroversial or to the liking of the lawyers who appeared before him, and he was inclined to bellow and roar on occasion and had lately developed the exasperating habit of suddenly becoming, or seeming to become, deaf. In passages at arms, especially with lawyer-politicians who mistook Prowse’s court for the floor of the House of Assembly, his opponents received short shrift. The wily and assertive Alfred Bishop Morine*, for example, was, for repeatedly refusing to sit down, called by his Honour “a low – very low – man. . . . Very disrespectful to the Court,” and ordered to be removed by the attendant constable. But Prowse could still rise to a much admired level, as with his ruling in the case of two neighbours and their conflicting witnesses. “Morrissey vs. Brien, for the recovery of a goat, was heard before Prowse, this morning, and gave rise to considerable merriment. From the evidence it appears that the plaintiff, Morrissey, lost a goat on Sunday last, which he alleged was now in the possession of Brien. Quite a number of witnesses were called to prove the rightful owner of the goat. One of the witnesses, when asked how he knew the goat, answered that ‘Any man who had a garden opposite, would easily know his neighbor’s goat.’ The manner in which the case is to be settled is, Constable Wheeler has been appointed deputy judge, he will take a drive on the Battery Road, this evening, and the kid which Morrissey has in his possession, is to be produced, and should it recognize the goat as its mother, or go to Morrissey’s house, he is the owner, or should it go to Brien’s house, he is the owner.”

At last Prowse retired, reluctantly, in January 1898, accompanied as always by verse compositions: an elegant poem by his friend Isabella Rogerson [Whiteford*] and another in a different manner – and level – of literary composition that began:

O, many a heartful mother’s prayer,

And prayer of many a drunkard’s wife,

Has reached high Heaven for all the care,

That marked thy long judicial life.

Retirement, however, did not diminish Prowse’s energies or narrow the range of his activities; it expanded them. In 1900 Cabot Tower, an imposing granite structure on the highest point of Signal Hill, overlooking the entrance to St John’s Harbour, was officially opened. Its initiation three years earlier was largely the result of Prowse’s unflagging energy and imagination as secretary of a committee formed to raise funds for a monument commemorating John Cabot*’s voyage of 1497 and the diamond jubilee of Victoria’s reign, while also providing a modern ships’ signalling facility – and, incidentally, eclipsing the modest brass tablet to Cabot placed at Halifax by the Royal Society of Canada. In 1901, to boost his modest pension, Prowse was appointed secretary of the fisheries board, which he helped to make a useful centre of information from other fishing nations. He was indefatigable in pressing for the passage of an act respecting libraries and the securing of a grant from American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to establish a library in St John’s, which had been bereft of such an institution since the destruction of the Athenæum in the great fire of 1892. With James Johnstone Rogerson*, James Patrick Howley, William Frederick Lloyd*, and others, he was a founder in 1906 of the Newfoundland Historical Society, which replaced the lapsed Newfoundland Historical and Statistical Society, and he was a frequent lecturer, as he had been in the earlier organization.

Prowse continued, but now in a torrent, writing his essays and periodical articles. In 1901, a typical year, he revised his long article on Newfoundland for the tenth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica; published essays on France in Newfoundland, Cromwell, the United States and the North American fisheries, French colonization and functionaries, and the life of Jean Serres, a Huguenot galley-slave, in journals on both sides of the Atlantic; and contributed a paper on the Treaty Shore question to the Canadian Law Review (Toronto) and a regular column on the military strategy of the South African War to the Daily News. At the same time he was drafting essays soon to appear in the newly founded Newfoundland Quarterly and in the Cornhill (London) and McClure’s (New York) magazines: a sketch of the experiences of “an old colonial judge” on circuit, a singular record of the practice of “wracking,” or looting, shipwrecks among coastal people, memories of hunting and fishing over a long lifetime, the growing of hardy annuals in the thin soil and short summers of Newfoundland, obituaries of his contemporaries as they passed on before him, and, as always, gasconading essays “booming” Newfoundland with wit and style.

In this endeavour his Newfoundland guide book (1905) was the best known. It was aimed at informing travellers about the colony’s people and resources, particularly the increasing number of hunting and fishing visitors, to attract whom Prowse included contributions from some who had already explored the island’s forests, barrens, and streams. John Guille Millais and other famous English sporting figures were guests of the hospitable Prowse and among his correspondents. Millais, who returned several times to hunt and to paint, has preserved a sketch of the Prowse of these years, hunting for snipe on the marshes one October morning. “The Judge, with his hat on the back of his head and a pair of bedroom slippers on his feet (‘Ye get wet anyhow, my boy’), jumped over the streams and fences like a two-year-old, working a somewhat wild pointer, and so, whistling and prancing from marsh to marsh, he covered the country in a manner that quite astonished me. Nor shall I forget his charming disregard for appearances, so characteristic of the true sportsman, when he kindly came to see me off by the crowded Sunday train, bearing in one hand a bucket full of potatoes and in the other . . . a big bag of worms.”

He was still active in his last year. Though an earlier plan for a short school history of Newfoundland had collapsed in the intricacies of denominational veto power over educational texts, material for the third edition of his History was completed and with the London printer as World War I loomed. He was reading again the novels and stories of his favourite, Thomas Hardy, and was still a familiar figure in St John’s, where his old habit, in making a purchase, of plonking down what he judged to be its proper worth continued to secure him the prompt and attentive service of shop clerks. But he was forgetful of ordinary things (his wife would sew his mittens to the sleeves of his overcoat) and, the children all gone away, he missed company. There was a short illness just before the morning of 23 Jan. 1914, when he fell downstairs; on the 27th he was found dead in his chair shortly before noon. His wife died within a month. The obituaries record of him a “pertinacity that recognized neither rebuff nor failure.” In the House of Assembly Premier Sir Edward Patrick Morris* remarked, “He was a man of wonderful enterprises. There is not a branch of the public life of the Colony that he was not at some time identified with.” And these words from a severe editor: “To this country he was Judge Prowse; to the coming generations . . . he will be remembered best as Prowse the historian.”

[Daniel Woodley Prowse is the subject of a brilliant one-man play, Judge Prowse presiding (1989), by the actor and writer Frank Holden.

Genealogical details were provided by K. J. R. Prowse of Deer Lake, Nfld, the subject’s only surviving nephew. Anecdotes concerning him have been collected by the author from Mr Prowse, Len Murphy, and the late Harry Conroy, Captain Colin Story, and Mrs Beatrice [Story] Gaze.

The first edition of A history of Newfoundland from the English, colonial, and foreign records appeared at London and New York in 1895, and has been reprinted (Belleville, Ont., 1972); the second edition was published in London in 1896, and the third, with Prowse’s revisions and additional material supplied by James R. Thoms and F. Burnham Gill, at St John’s in 1971. An account of the third edition’s troubled history appears in my article, “Judge Prowse: historian and publicist,” Newfoundland Quarterly (St John’s), 68 (1971–72), no.4: 19–25.

Just before his retirement, Prowse published The justices’ manual . . . (2nd ed., St John’s, 1898), a revised version of his 1877 Manual for magistrates thrice the size of the original. He also prepared second and third editions of The Newfoundland guide book . . . (London), both issued in 1911.

A facsimile reproduction of Prowse’s 1897 memorandum to Governor Murray and the negative response to it, drawn from Murray’s private papers, appears in the third edition of the History, pp.677–95. Autobiographical details appear also in an article which Prowse wrote late in his life, “Random recollections,” Christmas Post (St John’s), 1913: 12 (copy available at the Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Memorial Univ. of Nfld, St John’s). g.m.s.]

Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Arch., MF-270 (D. W. Prowse scrapbook). Courier (St John’s), 29 Jan. 1868. Daily News (St John’s), 7 June, 14 Nov. 1895; 28 Jan. 1914. Evening Telegram (St John’s), 29 June, 13–14 Nov. 1895; 28 Jan. 1914. Morning Chronicle (St John’s), 15 Oct. 1867, 1 March 1869, 16 April 1870. Royal Gazette and Newfoundland Advertiser (St John’s), August–December 1907. Times (London), 28 July 1859. J. E. Candow, “Daniel Woodley Prowse and the origin of Cabot Tower” and “Cabot Tower: the Prowse–‘Mariner’ correspondence,” Parks Canada, National hist. parks and sites branch, Research Bull. (Ottawa), nos.155 and 156 (both issued 1981). St John Chadwick, Newfoundland: island into province (Cambridge, Eng., 1967), c.3. Encyclopedia of Nfld (Smallwood et al.), 1: 687–88. Philip Gosse, An apple a day (London, 1948), c.8. McKay v. Prowse (1878), Newfoundland Reports (St John’s), 6: 166–68. Keith Matthews, “Historical fence building: a critique of the historiography of Newfoundland,” Newfoundland Quarterly, 74 (1978–79), no.1: 21–30; Lectures on the history of Newfoundland, 1500–1830 (St John’s, 1988). J. G. Millais, Newfoundland and its untrodden ways (London, 1907; repr. New York, 1967), 79. M. P. Murphy, Pathways through yesteryear: historic tales of old St John’s, ed. G. S. Moore (St John’s, 1976), 147. Nfld, House of Assembly, Journal, 1869–97, app., reports of police magistrates. Newfoundland Hist. Soc., Constitution of the Newfoundland Historical Society (St John’s, 1906; copy in its arch., St John’s). G. M. Story, “D. W. Prowse and nineteenth-century colonial historiography,” in Newfoundland Hist. Soc., Newfoundland history 1986: proceedings of the first Newfoundland Historical Society conference . . . , ed. Shannon Ryan ([St John’s, 1986]), 34–45; “Judge Prowse (1834–1914),” Newfoundland Quarterly, 68, no.1: 15–25. F. F. Thompson, The French Shore problem in Newfoundland: an imperial study (Toronto, 1961), c.4. Isabella Whiteford Rogerson, The Victorian triumph and other poems (Toronto, 1898), 149.

G. M. Story, “PROWSE, DANIEL WOODLEY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/prowse_daniel_woodley_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/prowse_daniel_woodley_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | G. M. Story |

| Title of Article: | PROWSE, DANIEL WOODLEY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |