Source: Link

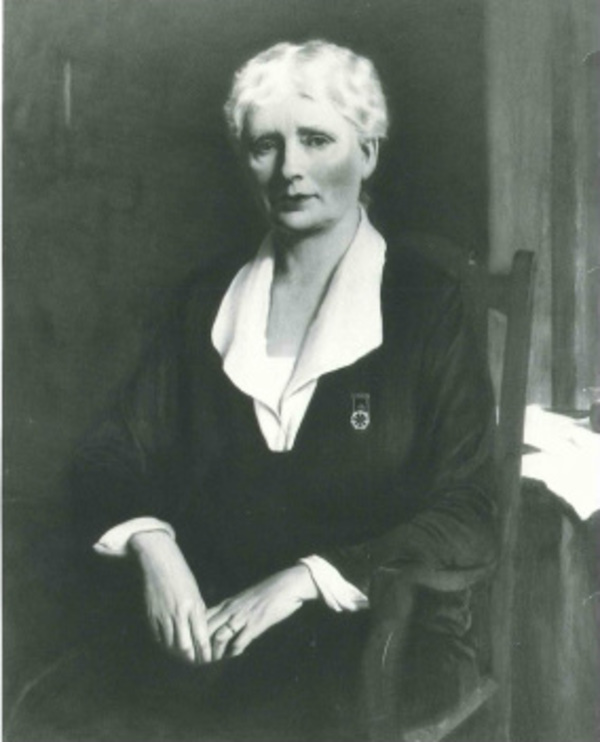

POLSON, MARGARET SMITH (Murray), social reformer, magazine editor, and founder of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire; b. 1 June 1844 in Paisley, Scotland, daughter of Margaret Maclean and William Polson, a starch manufacturer; m. there 20 July 1865 John Clark Murray*, and they had one son and four daughters; d. 27 Jan. 1927 in Montreal.

As a child, Margaret Polson exhibited considerable talent on the piano, but she was not given the opportunity to go abroad for advanced musical studies. She stayed at home and efficiently carried out the duties expected of the eldest daughter in a family of seven children. After her marriage at age 21, she moved to Upper Canada with her husband, who was then professor of philosophy at Queen’s College in Kingston. In 1872 he took up a similar appointment at McGill College in Montreal.

Margaret Polson Murray (she frequently signed using both surnames) was soon an active member of several charitable organizations in Montreal. In 1874 she and six other socially conscious women, including Mary McDougall [Cowans*], met to try to help the needy. The outcome of their deliberations was the foundation of the Montreal Young Women’s Christian Association the following year. The association’s initial objective was to meet young women from the country or abroad at the station or the dock and to “attend to their temporal, moral and spiritual welfare.” The need was great and the scope of the work expanded continuously. Murray took on the arduous task of honorary secretary.

Possessing a lively mind and ever-ready for self-improvement, Murray attended lectures of the Montreal Ladies’ Educational Association [see Anne Molson*]. She arranged a series of instructive entertainments on Saturday afternoons, encouraging others to better themselves. Continuing her musical interests, she helped to establish a choir at St Paul’s Presbyterian Church. Her concern for social issues and her writing skills were shown in her contributions to the Week (Toronto), in her article “Women’s clubs in America,” which appeared in the Nineteenth Century (London), and in “The housekeeper under protection,” published in the Contemporary Review (London). Her interest in children was evident when she founded and edited the Young Canadian (Montreal). Started in January 1891 and subtitled “an illustrated weekly magazine of patriotism for young Canadians,” the journal attracted well-known Canadian authors as contributors on a wide variety of subjects, but it did not last long. Always a staunch supporter of patriotic causes, Murray would lead a brigade of 600 Montreal women to a rally in Dominion Square in August 1914 when the British empire went to war with Germany.

Although Murray was one of seven women who were equally involved in starting the YWCA in Montreal, she was the individual most responsible for the founding of another important and enduring organization. She was in England in 1899 when the first casualties of the South African War became known. She reported that “the whole nation was staggered” but “ablaze with the spirit of giving . . . [in] a perfect stampede of war enthusiasm.” She believed that the women of Canada should seize the opportunity “to place themselves in the front rank of colonial patriotism” by forming an organization ready for prompt and united action. Her ardent support for the empire may have been sentimental, but her recognition that there was urgent need for comforts for soldiers, support for their dependants, and care for their graves was eminently pragmatic.

By the time Murray returned to Canada, she had a clear vision of the organization she wanted to establish. She immediately went to work. She had “one or two tentative meetings in her home,” and then on 13 Jan. 1900 she sent telegrams to the mayors of major Canadian cities asking, “Will the women of [your city] unite with the women of Montreal in federating as Daughters of the Empire, and inviting the women of Australia and New Zealand to join with them in sending to the Queen an expression of our devotion to the Empire, and an Emergency War Fund, to be expended as Her Majesty shall deem fit.” Two days later she outlined her ideas in a press release and gave interviews in Montreal newspapers.

On 1 Feb. 1900 Murray received word that the first local chapter had been formed on 15 January in Fredericton. Twenty-five women attended the meeting she organized in Montreal on 13 February for the founding of a national organization, the Federation of the Daughters of the Empire (its junior branch was named the Children of the Empire), with the motto Pro regina et patria. Once again, she chose to become honorary secretary, a strategic position in which she could keep the movement going.

Throughout the summer of 1900, with little help except, in all probability, that of her two unmarried daughters, she performed what she termed “absolutely prodigious work.” She drafted a detailed constitution, identified the aims and structure of the organization, and devised special titles for officers, such as queen regent, regent, and standard bearer. In addition, she set forth advice on how to form chapters, on procedures at meetings, and on projects to undertake. She envisaged a hierarchy of local, provincial, and national chapters in the various colonies with the imperial chapter in the mother country and Queen Victoria as patron. She established the Canadian headquarters in Montreal, but thought that Toronto, with its greater British population, would be more appropriate. By letter and telegram she contacted the wives of notables throughout the empire, secured the support of Lady Minto, wife of Canada’s governor-general, Lord Minto [Elliot*], and had the satisfaction of knowing that many chapters were being formed, including some in the United States.

Murray maintained an exhausting tempo during the summer and autumn of 1900. She sent cables, postcards, and as many as 500 letters a day “to well-selected people”; sought patrons of high status; filled orders for badges, cheque books, and copies of the organization’s constitution; encouraged the teaching of history in schools and the establishment of prizes and patriotic celebrations for Empire Day; contacted the Department of Indian Affairs so that native women might join; prepared a condensed statement of aims for wide circulation; raised funds; made speeches; organized a huge welcome dinner for returning soldiers; and was determined to “leave no stone unturned.”

The care of war graves was one of her vital concerns. To ensure that the graves (Canadian and Boer, especially those in isolated places) were identified and properly tended, she obtained the cooperation of the British War Office and the Cape Town branch of the Guild of Loyal Women of South Africa. The guild promised to identify Canadian graves, and “keep the sacred spots neat, . . . [and] place flowers at Xmas and Easter.” In Canada she set up a fund for this purpose with the full knowledge of Lady Minto, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, and the minister of militia and defence, Frederick William Borden*. War graves, however, became an interest of other organizations and rivalries soon developed among patriots.

In England in 1901 the Victoria League was formed with goals similar to Murray’s – to bring the people of the empire together and care for the war graves. The league viewed the work she did for her cause in Britain as an intrusion on its territory. In the summer of 1901 members of the Daughters in Toronto entreated their founder to return to London to strengthen their position. Edith Sarah Louisa Nordheimer [Boulton*], regent of the Ontario provincial chapter, sent Murray a telegram urging her to go and “make no concessions.” Although reluctant (she had resigned as honorary secretary in February 1901 possibly because of fatigue, but had withdrawn her resignation and was re-elected at the next annual meeting), Murray sailed again to Britain. In typical fashion, she worked vigorously, preparing the way for national chapters in England, Scotland, and Ireland and an imperial chapter in London with herself as secretary. She visited the offices of the Victoria League, where she “was received most delightfully” and affiliation was discussed. On her return to Montreal, however, she was shocked to receive what she later described as an “infamous” letter from the league, accusing her of “breach of faith” and demanding the names and addresses of her contacts in London. The league said it could not “countenance the formation of Branches of the Daughters of the Empire in the United Kingdom, as that would create endless confusion and destroy the whole idea of the Victoria League.”

Murray felt what she described as “the keen bitterness of misrepresentation” when the Ontario chapter failed to support her against the league. She also felt betrayed by Lady Minto, who not only publicized the league’s accusation but would try to take over her war graves work. Lady Minto had been enthusiastic about Murray’s efforts and had agreed to be honorary president of the Daughters and honorary treasurer of the war graves fund. In April 1901 Murray had learned in “speechless amazement” that Lady Minto was recommending that the graves work be postponed until the war was over. The following year, while the war still continued, she was outraged to find that Lady Minto had set up her own Canadian South African Memorial Association and was requesting that donations be sent only to it. In an unbearable “conflict between loyalty and insurrection,” Murray dared not speak publicly about her betrayal by the queen’s representative. She did protest strongly in private, but Lady Minto stood firm and a break in their relationship was inevitable.

Murray was not well after her second trip to England and in October 1901 she asked the women of the Ontario provincial chapter to assume leadership. They accepted and the Toronto office became the national headquarters. Under the new regime, the organization’s name was changed to the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, its motto became “One flag, one throne, one empire,” its badge was modified, and it was formally incorporated in Ontario. Edith Nordheimer was elected the first national president. Significantly, the ideals, purposes, constitution, and structure Murray had devised remained essentially unchanged. Even the committee on war graves continued its partnership with the Guild of Loyal Women of South Africa.

For a time, relationships between Murray and some of the women in Toronto were strained and there was confusion about her status in the Daughters. Some believed she had severed all ties, but that was not the case. She formed a new Founder’s chapter in Montreal, kept up an active correspondence with the national office, and frequently gave advice. Yet open hostility became apparent in 1906 when the standard bearer of the Hamilton chapter, while acknowledging that Murray was a “wonderfully gifted woman” who had done “stupendous work,” published a bitterly critical account of her early activities, accusing her of handing over the organization “in great disorder.” Murray protested vigorously and repeatedly to members of the national executive but, when they failed once again to support her, she broke her silence. In 1907 she privately published her own version of events in a passionate statement of 94 pages. She detailed the work she had done and described the healthy state of the Daughters (26 chapters established, many more in process) when she passed the head office over to Toronto. Since by that time the Mintos were no longer in Canada, she felt free to expose her feelings about Lady Minto and the Victoria League. Later, to the embarrassment of the national executive, she vindicated herself and even reproached Lady Minto in the pages of Echoes (Toronto), the IODE’s own journal.

Murray’s situation was not properly clarified until after the resignation of Mrs Nordheimer in 1911. In June 1912 she was officially invited to resume her “former position in the Order,” and she was later accorded honorary life membership. Her contribution was fully recognized in the elaborately illuminated address presented to her in April 1915 and by the jewelled badge given to her four years later by the primary chapters in Quebec.

On her death in January 1927 tributes arrived from around the world. At that time there were about 650 chapters of the IODE in Canada and some in other parts of the empire, representing a total membership of over 30,000. The IODE was one of the largest, most active, and best-organized women’s associations in Canada.

Margaret Polson Murray left a remarkable legacy. She had inspired innumerable women and men with a spirit of patriotism and charity, developed the idea of care for war graves, helped authenticate the participation of women in public life, and encouraged patriotic instruction for children. She bequeathed a vigorous, flexible organization. At the beginning of the 21st century, its mission is more squarely focused on Canada, with particular concern for immigrant and native women. Yet it retains strong links with Britain, its insignia still bears the crown and Union Jack, and it guards the tradition that the wife of the governor general is its patron.

Margaret Polson Murray was buried with her husband in Mount Royal Cemetery, Montreal.

Thirty-six issues of the Young Canadian, the children’s weekly edited by Margaret Smith Polson Murray between 28 Jan. and 30 Sept. 1891, are listed in the CIHM, Reg. Murray’s publications also include The Federation of the Daughters of the British Empire and the Children of the Empire (junior branch) (Montreal, 1900) and The Daughters of the Empire and the Children of the Empire (junior branch) and the South African Memorial Association: an unwritten chapter of two important imperial movements founded in Montreal, Feb. 1900 (Montreal, 1907).

General Register Office for Scotland (Edinburgh), Abbey (Paisley), reg. of marriages, 20 July 1865. MUA, MG 3083. NA, MG 28, I 8; I 17. Gazette (Montreal), 28 Jan., 3 Feb. 1927. Montreal Daily Star, 16 Jan. 1900, 3 Feb. 1927. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Encyclopedia Canadiana, ed. K. H. Pearson et al.([rev. ed.], 10v., Toronto, 1975). Lisa Gaudet, “Nation’s mothers, empire’s daughters: the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, 1920–1930” (ma thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1993). D. C. Hamilton, “Origins of the IODE: a Canadian women’s movement for God, king and country, 1900–1925” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., Fredericton, 1992). [Albert Murray?], “An intimate sketch,” Echoes (Toronto), March 1927: 5. C. G. Pickles, “Representing twentieth century Canadian colonial identity: the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire” (phd thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1996). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell).

Margaret Gillett, “POLSON, MARGARET SMITH (Murray),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/polson_margaret_smith_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/polson_margaret_smith_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Margaret Gillett |

| Title of Article: | POLSON, MARGARET SMITH (Murray) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |