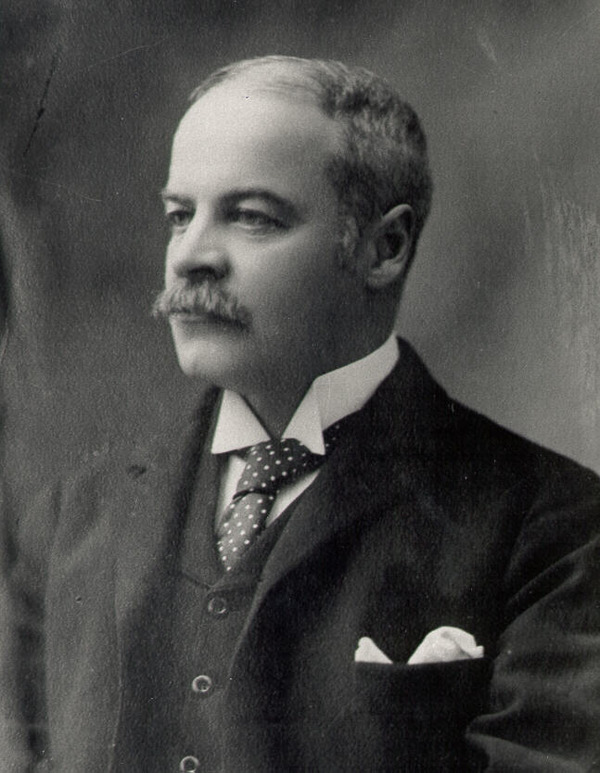

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PETERS, ARTHUR, lawyer and politician; b. 29 Aug. 1854 in Charlottetown, youngest son of James Horsfield Peters* and Mary Cunard; m. there 25 Sept. 1884 Amelia Jane Stewart, and they had two daughters and two sons; d. 29 Jan. 1908 in Charlottetown.

Arthur Peters was born into what passed for an aristocracy in 19th-century Prince Edward Island. As his obituary in the Charlottetown Guardian would note, he “enjoyed the advantage of aristocratic birth, ample fortune, a liberal education and the inherited aptitude for the legal profession.” Despite this “advantage,” young Peters was to live somewhat in the shadow of both his father, a judge, and his elder brother Frederick, a lawyer. Arthur’s early years followed an established family pattern. Educated first in Charlottetown by private tutors and later at Prince of Wales College, he then attended King’s College, in Nova Scotia, where he took an arts degree – the precise route that Frederick had followed. After a period in the law office of Edward Jarvis Hodgson in Charlottetown, Arthur went to England to read law, as had his father and brother. Having worked there with the prestigious G. Brough Allen and later with Richard Everard Webster, the 24-year-old Peters returned to the Island to be called to the bar in 1878; a year later he was admitted to the bar in England. By 1887 he had joined Frederick in a law practice in Charlottetown.

Peters’s marriage, in 1884 in St Peter’s Cathedral (Anglican), was undoubtedly a social highlight. His wife, Amelia Jane, was the daughter of the late Charles Stewart, a former mla for Kings County, 2nd District, the riding in which Peters would make his political début.

The last years of the 1880s, which saw Peters emerge as a rising member of the establishment in Prince Edward Island, constituted the high-water mark for the Island’s self-sufficient economy. From the early 1890s the province was to suffer a dramatic loss in population, a decline in the value of the output of its farms, fisheries, and manufactories, and a general economic malaise. Once the railway to the Pacific was completed and the federal government’s National Policy was adopted as the blueprint for transcontinental union, the Island was left isolated on the Atlantic margin. Consequently, politics there came to be dominated by issues that flowed from the Island’s declining role in an expanding federation and from its physical insularity: the preservation of Island representation in the dominion parliament, the negotiation of sufficient federal subsidies, and the continuing search for reliable, year-round communication with the mainland.

In 1890 Frederick Peters had formally entered Island politics as a member of the House of Assembly; the following year he became premier. A fellow Liberal, Arthur entered the legislature in 1893 as a member for 2nd Kings, which he would represent until his death. The Island’s political culture of the time was boisterous, parochial, and permeated by patronage and petty corruption. The Charlottetown newspapers, the Conservative Daily Examiner and the Liberal Daily Patriot, were fiercely partisan, putting the required political gloss on almost all reports of public affairs. In the election of 1893, for example, the Examiner charged the premier first with gerrymandering Kings in order to bring his inexperienced brother in as a candidate and then with enlisting the aid of a former premier, Louis Henry Davies*, to help rout the Conservative incumbents.

After his election in 1893, Arthur Peters lived very much in the political shadow of his brother. He spent the rest of the decade establishing his practice and raising a family, with politics as a part-time affair. By 1900 the firm of Peters, Peters, and Ings, which then consisted of just Arthur Peters and Ernest Ings, was located at one of Charlottetown’s best business addresses, Victoria Row on Richmond Street. In addition to law, it advertised “money to loan on instalments or straight loan.” Arthur’s family residence, Elmwood, was in a fashionable part of town, on the Sidmount estate of his father. Judge Peters had passed away in 1891, leaving his sons as trustees of his considerable holdings.

In 1897 Frederick Peters made a decision which astonished his party and would ultimately affect Arthur’s political career. He resigned as premier and moved to Victoria as a law partner of Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper*. Peters was succeeded as premier by Alexander Bannerman Warburton*, who, in turn, stepped down to accept a judgeship. Donald Farquharson assumed office next, but he too resigned, to contest a federal seat. Arthur Peters had joined his government in 1900 as attorney general and in December 1901, after Farquharson’s resignation, he was chosen party leader. On 2 January he was asked by Lieutenant Governor Peter Adolphus McIntyre to form a government. As the province greeted the new year with yet another premier, it was clear that the position was regarded by many as a way-stop on the road to better things.

Peters’s six years as premier and attorney general were to be dominated by established themes: the representation question, the subsidy, and winter communication. The representation issue was particularly vexing for Islanders and their Maritime neighbours. Given six seats in the House of Commons at the time of entry into confederation, the Island had witnessed during the 1890s a decline in both its relative proportion of the Canadian population and its absolute numbers. The figure of 109,078 people in 1891 was the peak; by 1901 it had fallen to 103,259. The redistribution of 1892 had seen the Island’s representation reduced to five seats, and in 1903 it was lowered to four. From the beginning to the end of Peters’s administration, a satisfactory resolution to the question eluded the Island and the region, though Peters was consistently forceful in his advocacy of the province’s case.

Before both the Supreme Court of Canada and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council Peters made strong arguments that the circumstances of the Island, in terms of its smallness and manner of joining confederation, demanded more than the number of seats allowed it under the British North America Act. New Brunswick, which joined the Island in the appeal to the Supreme Court, claimed, in addition, that its status as an original province should guarantee it the number of seats enjoyed in 1867. Nova Scotia made similar claims. In each case the arguments failed. It would not be until 1914, by which time the Island’s population justified only three seats, that Ottawa agreed to a compromise ensuring that no province should have fewer members in the commons than it had in the Senate. This agreement gave the Island four seats in the commons.

Peters found the question of cabinet representation for the Island frustrating as well. When the newly elected Donald Farquharson sought to occupy the place in cabinet vacated by Sir L. H. Davies, who had been appointed to the Supreme Court, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* was unsympathetic. Angry at what he saw as a slighting of the smallest province, Peters wrote bitterly in January 1902 that he did “not see why this Province should be ignored for the sake of the West.”

The subsidy question was equally difficult for the Maritimes and was a potent source of regional discontent. Comparisons with the subsidies given the new western provinces could not be avoided, and revealed to Maritimers what seemed to be unjust treatment. The case of the Island was particularly problematic. The costs of provincial administration and the interest on the Island’s debt had mounted. As the province’s economy faltered and the raising of revenues became more difficult, Ottawa was looked to for assistance. Against a background of frustration not only over representation but also over winter transportation, another issue that would not be resolved during Peters’s lifetime, the negotiations for larger subsidies occupied much of his time. With a Liberal government in Ottawa, Island Liberals were not subtle in their claim to have a special relationship with Laurier. “Vote for the Liberals and an increase to our subsidy” was the rallying cry in the provincial election of 1904. Success did not come quickly, but Peters and the other premiers did make limited progress at the dominion-provincial conference of October 1906. Unfortunately Peters died just days before the increased subsidy was announced in the provincial speech from the throne in February 1908.

As a provincial political leader, Arthur Peters was both respected and effective. Patronage appointments remained as much part of the electoral scene as ever, and a large part of the premier’s correspondence concerned the details of such things in 2nd Kings. He had reason to pay close attention to affairs there. In the election of 1904 he and his Conservative opponent, Harvey D. McEwen, received equal numbers of votes. It was not until after a by-election in March 1905, which Peters won by acclamation, that he returned to office.

In the social, sporting, and legal circles in which he moved, he was considered an ideal family man. When he fell ill in December 1907, most thought it a case of the influenza then common in town, and expected the vigorous 54-year-old premier back in his office in a week. It was not to be. On 29 January he died of Bright’s disease at Elmwood. When probated, his will, which left all his property to his wife, revealed a modest estate of just over $10,000, half of which came from a life-insurance policy. His obituary in the Charlottetown Guardian described him as a man who was “never a seeker after cheap popularity, and at times somewhat indifferent to the favour of the masses.” He would likely have thought it a fair assessment.

NA, MG 26, G: 61618; RG 31, C1, 1891, Prince Edward Island (mfm. at P.E.I. Museum, Geneal. Div.). PARO, RG 25, ser.20; Supreme Court of Prince Edward Island, Estates Div. records, liber 13: f.3; liber 17: ff.370–71 (mfm.). Charlottetown Guardian, 30 Jan. 1908. Daily Examiner (Charlottetown), 25 Sept. 1884; 17 Jan., 11 Feb. 1890; 21, 30 Nov., 1 Dec. 1893. Daily Patriot (Charlottetown), 17 Nov. 1893, 10 Nov. 1904. Canada’s smallest province: a history of P.E.I., ed. F. W. P. Bolger ([Charlottetown], 1973), 232–327. Directories, Atlantic prov., 1900; Canada, 1896/97; P.E.I., 1889/90, 1900. J. W. Driscoll, “Prince Edward Island and parliamentary representation: the beginnings of a Maritime regionalism” (ma thesis, Univ. of N.B., Fredericton, 1990). W. E. MacKinnon, The life of the party: a history of the Liberal party in Prince Edward Island (Summerside, P.E.I., 1973). P.E.I., Legislative Assembly, Journal, 8 Feb. 1908. Andrew Robb, “Michael A. McInnis, the Maple Leaf and migration from Prince Edward Island,” Island Magazine (Charlottetown), no.17 (summer 1985): 15–19. Frank Schwartz, “An economic history of Prince Edward Island,” Exploring Island history: a guide to the historical resources of Prince Edward Island, ed. Harry Baglole (Belfast, P.E.I., 1977), 93–116.

Andrew Robb, “PETERS, ARTHUR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/peters_arthur_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/peters_arthur_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Andrew Robb |

| Title of Article: | PETERS, ARTHUR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |