Source: Link

PEENAQUIM (Pe-na-koam, Penukwiim, translated as seen from afar, far seer, far off in sight, and far off dawn; also known as Onis tay say nah que im, Calf Rising in Sight, and Bull Collar), chief of the Blood tribe of the Blackfoot nation; b. c. 1810, probably in what is now southern Alberta, son of Two Suns; d. 1869 near the present city of Lethbridge, Alta.

From about 1840 until his death this Indian warrior was considered to be the leading chief of the Blood tribe, which hunted over much of what is now southern Alberta. Tribal tradition has still much to say about his deeds but it is difficult to assign dates or locations to such records. Peenaquim was a close friend of fellow chieftain Sotai-na*, and both had the reputation of being fearless in battle. On one occasion Peenaquim led a war party to raid the Crees. At the North Saskatchewan River they unexpectedly met a brigade of Hudson’s Bay Company boats. Peenaquim was recognized as a chief, exchanged gifts and clothing with the chief factor, possibly John Rowand*, and left the brigade in peace. When the Bloods shortly after discovered a Cree camp, Peenaquim walked boldly into it and shot their chief, Handsome Man. Not long after, near the Sweetgrass Hills, Peenaquim and fellow chief Calf Shirt [Onistah-sokaksin*] led a three-day pursuit of nine Cree raiders and surrounded and killed them. In another battle, against the Assiniboins, he cut off the hand of one of their warriors. His most famous battle was against some Crow Indians. While he and Sotai-na were spying on their camp, Peenaquim deliberately flashed a mirror to let them know they were being watched. When the Crows attacked, Peenaquim, then known as Bull Collar, killed a chief bearing the same name and Sotai-na did the same.

Peenaquim had a large tribal following, estimated at the time of his death as being 2,500 people. Of these, some 260 were from his own band; called the Fish Eaters (Mamyowis), they had received that distinctive name when starvation had forced them to eat fish, a food they normally abhorred.

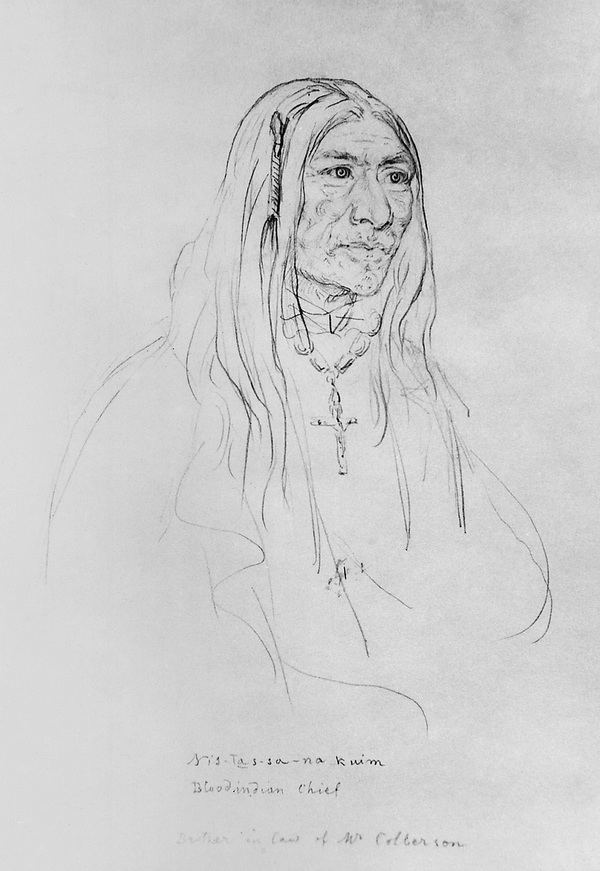

In about 1840, Peenaquim’s sister, Medicine Snake Woman, married Alexander Culbertson, chief trader at Fort Union on the Missouri River. This alliance gave the Americans great influence among the Bloods and, at the same time, made Peenaquim the most powerful chief in the Blackfoot nation. He received many gifts from the traders, and also carried on a limited trade himself. An entry for 26 March 1855 in the Fort Benton journal indicates the chief’s importance: “A party of Blood Indians arrived for trade, headed by Mr. Culbertsons Bro in Law, Gave them a salute and hoisted our flag.” When the American government negotiated a treaty with the Blackfoot tribes in 1855, Culbertson was prominent in the proceedings. The first to sign the treaty for the Bloods was Peenaquim, using his name Onis tay say nah que im [see Onistah Sokaksin].

Because of his close relationships with the Americans, Peenaquim usually hunted in southeastern Alberta and northern Montana, taking his tribe’s robes and dried meat to Fort Benton on the Missouri River. By 1866 the influx of gold seekers into Montana had resulted in several conflicts, and in that year the chief took his followers north to southern Alberta between the Belly and Red Deer rivers. They were in danger of attack by Crees, but Peenaquim successfully kept his warriors at peace during this trying period.

In 1869, Peenaquim was among the first of his band to die in a devastating smallpox epidemic. During the winter of 1869–70 no less than 630 Bloods were victims. Shortly before his death, Peenaquim spoke to his people: “The last hour of Pe-na-koam has come, but to his people he says, Be brave; separate into small parties, so that this disease will have less power to kill you; be strong to fight our enemies the Crees, and be able to destroy them.” Peenaquim was buried in the valley of the Oldman River, just north of Lethbridge. He was described by one Montanan as “the greatest chief Major Culbertson ever saw amongst the Blackfeet – having 10 wives and 100 horses,” and William Francis Butler*, a visitor to Rocky Mountain House, said he was “one of their greatest men.” Peenaquim’s chieftainship was taken for a few months by his older brother, Kyiyo-siksinum (Black Bear), and when the latter died in 1870 his nephew Mekaisto* (Red Crow) became chief of the Bloods and famous in his own right.

Private archives, H. A. Dempsey (Calgary), Interviews with John Cotton, 1953; Percy Creighton, 1954; Charlie Pantherbone, 1954; and Frank Red Crow, 1954 (unpublished field notes). W. F. Butler, The great lone land: a narrative of travel and adventure in the north-west of America (2nd ed., London, 1872). “The Fort Benton journal, 1854–1856,” ed. Anne McDonnell, Mont. Hist. Soc., Contributions (Helena), X (1940), 13, 26. H. A. Dempsey, Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet (Edmonton, 1972), 38–39. S. H. Middleton, Kainai chieftainship; history, evolution, and culture of the Blood Indians; origin of the sun-dance (Lethbridge, Alta., [1953]), 116, 133, 136, 157–58. J. W. Schultz and J. L. Donaldson, The sun god’s children (Boston and New York, 1930), 170. J. H. Bradley, “Characteristics, habits, and customs of the Blackfeet Indians,” Mont. Hist. Soc., Contributions, IX, (1923), 256.

Hugh A. Dempsey, “PEENAQUIM (Pe-na-koam, Penukwiim, Onis tay say nah que im) (Calf Rising in Sight, Bull Collar),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/peenaquim_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/peenaquim_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hugh A. Dempsey |

| Title of Article: | PEENAQUIM (Pe-na-koam, Penukwiim, Onis tay say nah que im) (Calf Rising in Sight, Bull Collar) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |