Source: Link

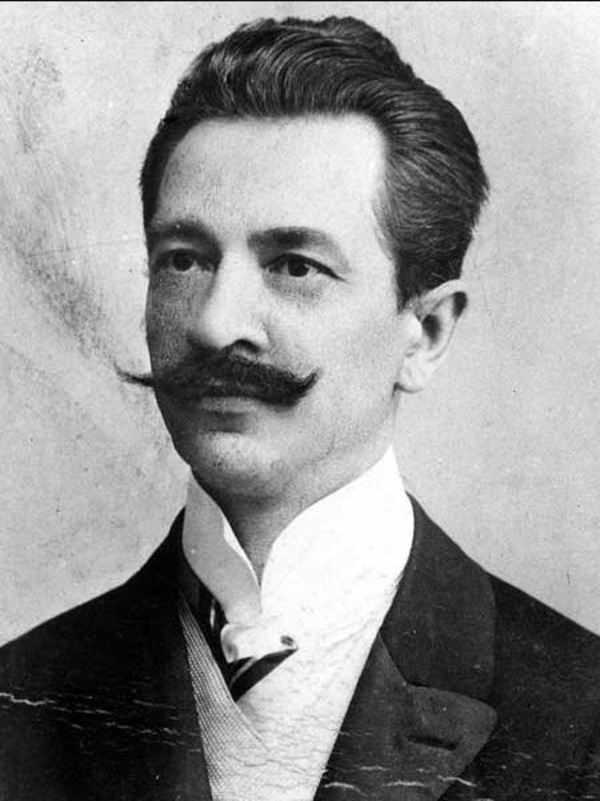

OLESKÓW, JÓSEF (transliterated from the Cyrillic as Osyp Oleskiv; also written Joseph Oleskiw, but he signed his Canadian correspondence Jósef Olesków), immigration agent; b. 28 Sept. 1860 in Skvariava Nova (Ukraine); m. twice, and two sons and two daughters were born of the first marriage; d. 18 Oct. 1903 in Sokal (Ukraine).

Jósef Olesków was born in Galicia, a province of the Austrian empire inhabited by people of Ukrainian and Polish origins. His father, a Greek (Eastern) Catholic parish priest, was a member of the rural élite. Olesków studied geography and agriculture at the University of Lemberg (Lviv, Ukraine), and earned a phd from the University of Erfurt in Germany. He was appointed professor of agronomy at the teacher’s college in Lemberg.

The agrarian policies of the Austro-Hungarian government during the late 19th century adversely affected the peasantry in Galicia by creating land shortages and a declining standard of living. Emigration to North and South America was thought to be a solution to the problem. Although some Ukrainians may have come to Canada at an earlier date, the first recorded immigrants, Ivan Pillipiw and Wasyl Eleniak, arrived in 1891, to explore the opportunities for settlement. They were followed by a trickle of immigrants. Ukrainian leadership was divided on the issue of emigration, however. Olesków was among those who favoured it, but he believed that only carefully planned emigration, rather than a mass exodus, would improve the socio-economic condition of his countrymen, both those leaving and those remaining at home. Over 10,000 Ukrainians had been enticed by offers of free transportation to settle in Brazil and Argentina. From the letters they sent home Olesków learned that conditions there were often more difficult than those in Galicia. So he turned his attention to Canada. On 16 March 1895 he contacted the Department of the Interior requesting information. As a result of the contacts he established, he wrote a pamphlet, Pro vilni zemli (About free lands), published by the Prosvita Society, a prominent Ukrainian educational organization, in July 1895. In this thoughtfully executed work, he strongly endorsed Canada as the most suitable country for Ukrainian agricultural settlement.

On 25 July Olesków and a representative of the farming community, Ivan Dorundiak, set out on a fact-finding mission as guests of the Canadian government. They arrived in Montreal on 12 August, met with immigration officials in Ottawa, and proceeded to Winnipeg, where a German-speaking guide, Hugo Carstens*, was assigned to them by the Winnipeg office of the dominion lands branch. Olesków was particularly interested in the district of Stony Plain (Alta), west of Edmonton, where a number of German settlements had been started. In the region of Beaverhill Creek, northeast of Edmonton, he encountered 16 Ukrainian families who had recently taken up homesteads. Following an inspection of Vancouver Island, he returned to Winnipeg and then travelled to Ottawa via the United States.

In a memorandum prepared for the Canadian government Olesków reaffirmed his faith in Canada and asked, without success, that the government provide subsidies for Ukrainian immigrants. On his return home he held a conference in Lemberg at which an emigrant aid committee was established, consisting of numerous prominent citizens. Olesków continued his enthusiastic promotion of Canada in another booklet, O emigratsii (About emigration), and a brochure in Polish, Rolnictwo za okeanem a przesiedlna emigracja (Farming beyond the ocean and transplanted emigration). Both circulated widely and the author was inundated with visitors and requests for advice on immigration to Canada.

In February 1896 Olesków informed officials in Ottawa that he had about 30 hand-picked families ready to resettle in western Canada. Chosen on the basis of their adaptability and their capital, these settlers were well prepared for the hardships of pioneer life in Canada. Olesków made sure that even their clothing conformed to that of other Canadians, so as not to alienate Canadian residents. Led by Olesków’s brother, Wladimir, the contingent arrived in Quebec City on 30 April 1896. All but three families settled near Edna (Star, Alta).

After the Liberal party under Wilfrid Laurier* assumed power in Canada in June 1896, the government began promotion of large-scale immigration from eastern Europe. In one of his numerous letters to the Department of the Interior, Olesków had urged the appointment of a “Superintendent of Galician Emigration” to act as an intermediary between the government and the Ukrainian settlers. Ottawa refused, but appointed Cyril Genik*, whom Olesków had persuaded to immigrate in 1896, interpreter in Winnipeg later that same year. Genik would become a major influence in the subsequent Ukrainian settlement of western Canada. William Forsythe McCreary, named commissioner of immigration for Canada the following year, recognized Olesków as an important source of reliable settlers. In January 1898 Olesków met with Canadian representatives in London and became Canada’s immigration agent in Galicia. In a confidential arrangement, the federal government provided him with a subsidy to cover the costs of printing and advertising and agreed to pay him $2.50 (half the amount paid to shipping agents) for every adult immigrant he recruited. Olesków’s work for Canada had to remain confidential because of growing opposition in Galicia to his activities. Between 1898 and 1900 the Department of the Interior spent nearly $6,000 assisting Olesków, but it refused to establish a formal Canadian immigration office in Lemberg.

Olesków’s activities proved to be counter-productive to his concept of selective emigration. Profiting from his dissemination of information on Canada, steamship agents intensified their recruitment of prospective settlers; mass emigration occurred. Many suffered severe hardships because of unpreparedness and lack of money. Olesków had always urged poor emigrants to go to the United States, where they could earn money before homesteading in Canada. The number of immigrants he directly recruited is unknown, but it was probably no more than several hundred families. By 1914, however, about 170,000 Ukrainians had settled in Canada, thus becoming the largest Slavic group in the country. In 1981 nearly 800,000 Canadians would claim Ukrainian ancestry.

In 1900 Jósef Olesków was forced by political pressure, the death of his first wife, and his departure from Lemberg to cease his promotion of emigration. He had been appointed principal of a teacher’s college in Sokal. Three years later he died suddenly at age 43. Although initially esteemed as the “father of Ukrainian emigration to Canada,” he was soon forgotten, both in Ukraine and in Canada. He was indeed a man of vision but he had seriously misjudged his countrymen’s future in Canada. He opposed mass emigration of poor peasants, underestimating their tenacity and resourcefulness in coping with the rigours of pioneer life. In his correspondence with Ottawa, he stressed the assimilationist tendencies of the Ukrainians, implying that they would be quickly and easily integrated into the Anglo-Celtic culture. In reality, Ukrainians more than any other minority would resist the loss of their cultural identity and would be in the forefront of efforts to redefine Canada as a multicultural society.

[Jósef Olesków is the author of two pamphlets in Ukrainian, Pro vilni zemli (Lviv, [Ukraine], 1895; repr. Winnipeg, 1975, with an added title-page in English, Free lands) and O emigratsii (Lviv, 1895), and of one in Polish, Rolnictwo za okeanem a przesiedlna emigracja ([Lviv], 1896), on the subject of immigration to Canada. The extensive research of Vladimir Julian Kaye brought to light the role of Olesków in the settlement of Ukrainians in Canada. Little work on this aspect of Ukrainian-Canadian history has been carried out since the publication of his Early Ukrainian settlements in Canada, 1895–1900; Dr. Jósef Olesków’s role in the settlement of the Canadian northwest (Toronto, 1964), which remains the only exhaustive source for documentation on Olesków. o.w.g.]

J.-P. Himka, “The background to emigration: Ukrainians of Galicia and Bukovyna, 1848–1914,” and V. J. Kaye and Frances Swyripa, “Settlement and colonization,” in A heritage in transition: essays in the history of Ukrainians in Canada, ed. M. R. Lupul (Toronto, 1982), 11–31 and 32–58. M. H. Marunchak, Biographical dictionary to the history of Ukrainian Canadians (Winnipeg, 1986) [text in Ukrainian]. Jaroslav Petryshyn, Peasants in the promised land: Canada and the Ukrainians, 1891–1914 (Toronto, 1985). Julian Stechishin, History of Ukrainian settlements in Canada [text in Ukrainian] (Edmonton, 1975); translated by Isidore Goresky as A history of Ukrainian settlement in Canada (Winnipeg, 1992). Statistical tables to “The Ukrainian Canadians: a history”, comp. M. H. Marunchak (Winnipeg, 1986).

O. W. Gerus, “OLESKÓW, JÓSEF (Osyp Oleskiv, Joseph Oleskiw),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oleskow_josef_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/oleskow_josef_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | O. W. Gerus |

| Title of Article: | OLESKÓW, JÓSEF (Osyp Oleskiv, Joseph Oleskiw) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |