Source: Link

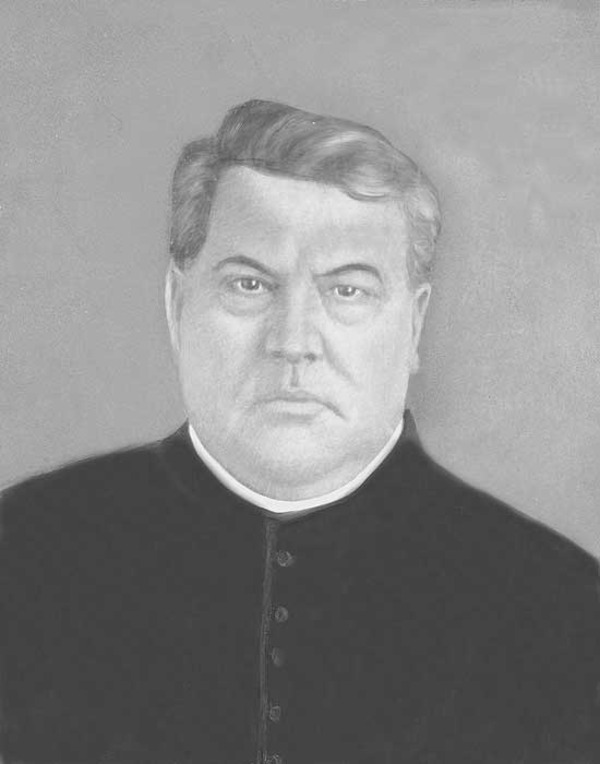

LANGEVIN, ANTOINE, Roman Catholic priest and vicar general; b. 7 Feb. 1802 in Beauport, Lower Canada, son of Antoine Langevin, a day-labourer, and Catherine Leclaire; d. 11 April 1857 in Saint-Basile, N.B.

Antoine Langevin entered the Séminaire de Nicolet in 1826. Four years later he was appointed prefect of studies, a post he held until 1833; he probably undertook studies in theology at the same time. On 29 Sept. 1833 he was ordained priest at Quebec, and shortly after he was appointed curate at Nicolet.

In 1835 Langevin became parish priest of Saint-Basile, in the Madawaska region of New Brunswick. This parish, founded in 1792, was the only one then established canonically in Madawaska. By the time Langevin came it boasted a chapel, sacristy, and presbytery in good condition. In addition he looked after two chapels, one at Saint-Bruno (Van Buren, Maine), 15 miles downstream from Saint-Basile, and the other at Sainte-Luce (St Luce Station, Maine), at the same distance upstream. Although the Madawaska mission, extending 70 miles along the Saint John River, was part of the diocese of Charlottetown (established in 1829), the bishop, Angus Bernard MacEachern*, had left various administrative powers to the archbishop of Quebec. Thus it fell to Archbishop Joseph Signay* to appoint the French Canadian priests responsible for ministering to a population that by 1830 had risen to 2,612 settlers of Acadian and French Canadian origin. Langevin had to adapt to a rather primitive existence which none the less offered some compensations. As his predecessor, François-Xavier-Romuald Mercier, noted in 1834, “If the missionary at Madawaska has the misfortune to be isolated, he has on the other hand the joy of having a large number of virtuous settlers who love their religion and practise it faithfully.”

In 1838 Langevin was appointed vicar general of the Madawaska mission by Bernard Donald Macdonald, the new bishop of Charlottetown, in the course of a pastoral visit to New Brunswick. During his 22 years at Saint-Basile, Langevin was remarkably successful. He worked zealously and unremittingly in a number of spheres. His correspondence with Signay shows that, despite his energy and devotion to his widely scattered flock, he could not cope with the amount of work. Many of the faithful had to be satisfied with eight or nine visits annually from their parish priest, since more frequent visits could not be managed, given the distances and primitive means of transportation involved. Langevin repeatedly asked Signay to create other parishes with a resident priest. Thanks to his persistent requests, the parishes of Saint-Bruno and Sainte-Luce were founded in 1838 and 1843 respectively.

The Malecites of the region were also the object of Langevin’s pastoral concern. He used his good relations with the lieutenant governor of New Brunswick, Sir John Harvey, to obtain an annual sum of £50 from the government so that he could secure the help of a priest for his ministry at the Tobique Indian Reserve and at Saint-Bruno, where there were a number of Malecite families.

Langevin was reputed to be a good administrator. He made judicious use of the fabrique’s lands and of some properties in the region owned by the archbishop, renting them to farmers or cultivating them to make them profitable for their owners. During his years there the settlement of the Madawaska region made considerable progress. The population increased noticeably and the area prospered. Hence Langevin was able to replace the old presbytery with a new one of impressive size, and he started construction of a new church, which was still unfinished at the end of his life. He seems to have had enough money himself to lend funds at interest to various local people. From 1839 until his death he lent substantial sums (amounting to at least £1,700) to the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière.

In the field of education Langevin stood out as a leader. He encouraged the setting up of primary schools and bolstered the dedication of itinerant teachers. But his zeal was especially evident in the assistance he gave to the young men of the Madawaska area to enable them to pursue their studies at college, particularly at the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière. From 1839 Langevin, with Signay’s permission, used the income from the lands belonging to the archbishop to pay the students’ board, “in the hope of making ecclesiastics of them for this poor diocese . . . which needs them so badly.” Part of his own income was put to the same purpose. Between 1855 and 1857 he gave the college donations totalling £2,000 for bursaries that are still offered. The college inherited his estate, estimated to be worth £3,079.

The vicar general’s influence and action also extended to the political sphere. He maintained good relations with the authorities in New Brunswick, especially with Harvey, the lieutenant governor, who was Langevin’s guest at the time of his visit to the Madawaska region during the quarrel between Maine and New Brunswick over the border between them. Langevin was an ardent defender of all things British, and it may have been because of his control over his parishioners that they remained quiet during the conflict. He continued to minister to the parishes which found themselves on the American side of the border when the Webster–Ashburton Treaty was concluded in 1842 [see James Bucknall Bucknall Estcourt]. Harvey wrote concerning Langevin: “The Madawaska region and the entire province of New Brunswick were fortunate in having such an enlightened guide in such a critical period of their history.”

Although Langevin was generally esteemed during his years at Saint-Basile, his authoritarian, domineering, and sometimes uncompromising character occasionally aroused the displeasure, and even the hostility, of some parishioners. In 1849, for example, 44 of them signed a petition to Signay complaining about the conflicts between Langevin and the fabrique over control of parish funds, and stressing that they no longer had confidence in “a man whose daily conduct only tends to tyranny, and who takes pleasure in calling [us] morons and ranking [us] with brute beasts, whenever the opportunity arises.” On the other hand, nine of the region’s leading citizens wrote to Signay some months later that they were “perfectly satisfied” with their parish priest’s behaviour.

These conflicts darkened the last years of Antoine Langevin’s ministry. “A man with superior administrative ability,” of “indomitable energy, unflagging perseverance, [and] an authoritarian character,” to quote the Reverend Thomas Albert, the historian of Madawaska, Langevin stood out as one of the region’s great benefactors and as a zealous priest who generously helped Madawaskans to weather one of the most difficult periods of their history. He died prematurely in his parish on 11 April 1857, and was buried on 20 April in the church of Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (La Pocatière).

[The author wishes to thank Mgr Ernest Lang of Edmundston, N.B., for information on Antoine Langevin. g.r.m.]

AAQ, 311 CN, IV: 122–24, 127–34, 137–38, 140–42, 147–48, 150–54, 163; 60 CN, II: 88. ANQ-Q, CE1-5, 7 févr. 1802; CE3-12, 20 avril 1857; CN2-30, 29 mars 1841; 29 juill. 1842; 12, 21 mai 1852; 6 déc. 1856; 10 mai 1857. Allaire, Dictionnaire, 1: 302. Tanguay, Répertoire (1893), 214. Thomas Albert, Histoire du Madawaska d’après les recherches historiques de Patrick Therriault et les notes manuscrites de Prudent L. Mercure (Québec, 1920). H. G. Classen, Thrust and counterthrust: the genesis of the Canada–United States boundary (Don Mills [Toronto], 1965). Douville, Hist. du collège-séminaire de Nicolet. Wilfrid Lebon, Histoire du collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (2v., Québec, 1948–49). Roger Paradis, “La bourse Langevin: une page de l’éducation des Acadiens au Madawaska,” Soc. hist. acadienne, Cahiers (Moncton, N.-B.), 7 (1976): 118–30. “Une grande et noble figure de l’histoire du Madawaska, le grand vicaire Langevin, 1835–1857,” Le Brayon (Edmundston), 3 (1975), no.2: 16–19.

Guy R. Michaud, “LANGEVIN, ANTOINE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 2, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/langevin_antoine_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/langevin_antoine_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Guy R. Michaud |

| Title of Article: | LANGEVIN, ANTOINE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 2, 2024 |