Source: Link

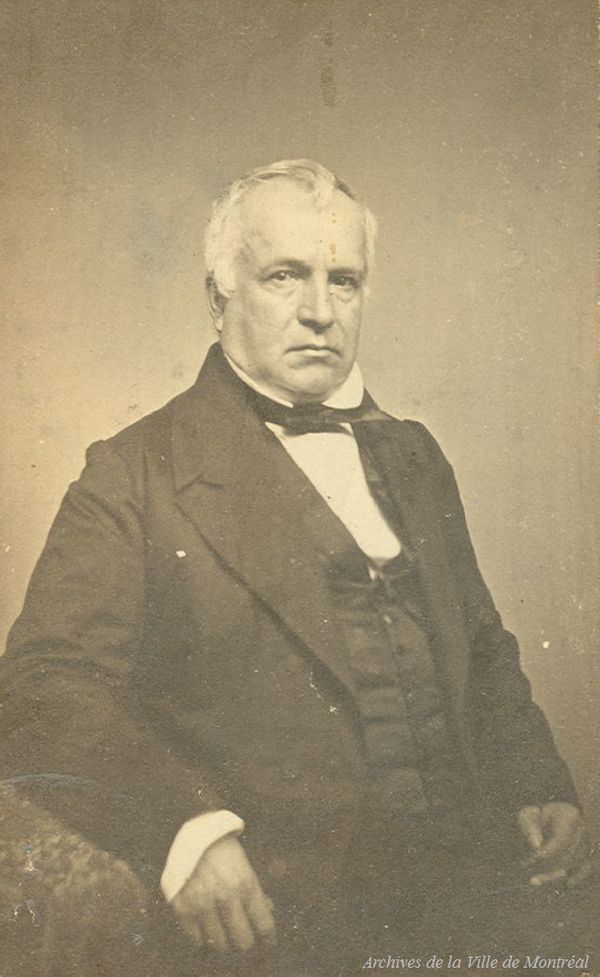

LA FONTAINE (Ménard, dit La Fontaine), Sir LOUIS-HIPPOLYTE (he signed LaFontaine; the spelling Hypolite is used on certain documents including his certificate of baptism), politician and judge; b. 4 Oct. 1807 at Boucherville, Lower Canada, third son of Antoine Ménard, dit La Fontaine, a carpenter, and Marie-Josephte Fontaine, dit Bienvenue; d. 26 Feb. 1864 at Montreal.

Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine attracted attention at an early age. At the Collège de Montréal, where he began classical studies in 1820, he rapidly distinguished himself by a love of work and an astonishing memory. His fellow students called him “the big brain.” He was considered the most gifted, although he always came second in his class. (According to an oft-told story Louis-Joseph Plessis, who always was first in the class, later became a drunkard and for several years sponged off La Fontaine.) At recess, La Fontaine was acknowledged as the most energetic and most skilful, particularly at tennis in which he had no rival. Because of his strong personality and competitive spirit, however, he could not put up with the college régime for long. At the end of his belles-lettres year he left to become a clerk in the office of the lawyer François Roy.

Called to the bar in 1828, La Fontaine rapidly built up a substantial practice and soon was known as a gifted advocate. He made an advantageous marriage at this time. On 9 July 1831, at Quebec, he married Adèle, the daughter of Amable Berthelot*, a wealthy lawyer, bibliophile, collector, and politician. La Fontaine thus laid the foundations of a fortune and legal career both of which would be noteworthy. Even when he was a law student he had become interested in politics. At the request of his friends Ludger Duvernay* and Augustin-Norbert Morin, he published his critical views on law and politics in La Minerve. Hence it is not surprising that he took part in electoral campaigns at the end of the 1820s. In 1830 he entered active politics, and was easily elected to the House of Assembly of Lower Canada for Terrebonne. He was re-elected just as easily in 1834.

In the assembly the young member rapidly demonstrated his solid support of the most impassioned leaders, Louis Bourdages* and Louis-Joseph Papineau*. On 21 May 1832, he accompanied Papineau into the thick of the riot at Place d’Armes, Montreal, which marked the election of Daniel Tracey*; and in 1834, after mha Dominique Mondelet accepted a post on the Executive Council and his brother Charles-Elzéar Mondelet* opposed the 92 Resolutions, La Fontaine replied for the Patriote party in a violent pamphlet entitled Les deux girouettes, ou l’hypocrisie démasquée. Until the beginning of the insurrection in 1837, he loyally went with Papineau to the stormiest meetings, and appeared in Quebec dressed in the Patriote style in a jacket of cloth woven locally. And he was becoming known as one of the most anticlerical mhas; his pamphlet, Notes sur l’inamovibilité des curés dans le Bas-Canada (1837), recalled to Bishop Joseph Signay* of Quebec the acid writings of the precursors of the French Revolution. But it seems that the approach of hostilities caused a totally unexpected reversal of his feelings, which he never explained. Some saw political opportunism in the change, but it is more likely that La Fontaine, a practical politician, lost confidence at that moment in both the party’s strategy and some of its objectives. He had been aggressive and fiery; from November 1837 on, he showed a surprising skill for political manoeuvre and compromise. He would later prove to have a profound understanding of the principles of the British constitution and of their importance for the survival of French Canadians.

Four days before armed violence broke out at Saint-Denis, on 23 Nov. 1837, La Fontaine wrote to the governor, Lord Gosford [Acheson*], urging him to convene parliament immediately. He then went to Quebec with his colleague James Leslie* for a personal interview with the governor on 5 December bringing to him a new request, signed this time by 13 other mhas, including his father-in-law Amable Berthelot and his friend Augustin-Norbert Morin. When Gosford refused to call parliament, La Fontaine left for London, arriving at the end of December. He met frequently with the parliamentary representatives of the English reform party, Edward Ellice and Joseph Hume, before going to Paris in March 1838. Returning to America on 11 June, he stopped at Saratoga, N.Y., to greet Papineau and arrived at Montreal on 23 June. There he rejoined his wife; for six months she had devoted herself to visiting her husband’s former colleagues imprisoned since his departure, and had been endeavouring, with considerable sacrifice, to meet the needs of their families. When hostilities resumed in November, La Fontaine himself was imprisoned, as were his friend and partner Joseph-Amable Berthelot* and other politicians, including Denis-Benjamin Viger, Jean-Joseph Girouard*, and Charles-Elzéar Mondelet. He was released on 13 December after questioning and no charges were laid against him.

During the events of this year, La Fontaine was unquestionably the man of compromise, and the skilful spokesman both of the imprisoned Patriotes and of the former moderates who had put their trust in the flexibility of British institutions and who considered La Fontaine’s visit to London a final attempt at a constitutional solution to Lower Canada’s problems. He had won the confidence of Canadian politicians and the respect of the government. It was he who was chosen as legal adviser to the prisoners granted amnesty by Lord Durham [Lambton*] in June 1838, and who served as intermediary between the government and those deported to Bermuda. He also placed himself at the disposal of the governor’s secretaries, Charles Buller* and Edward Gibbon Wakefield, for discussions on the general political situation. Ultimately it was he who drafted the documents that led the authorities to free him and his friends late in 1838. Most important, in his exchanges with Lord Gosford, Edward Ellice, Joseph Hume, Charles Buller, and Edward Gibbon Wakefield, he put forward the most lucid analysis of French Canada’s situation and most clearly outlined the remedies for its troubles. Thus, he mapped out his own programme in the decade to come.

For the immediate future, La Fontaine insisted on two points: a general amnesty for those guilty of rebellion, and an indemnity for its victims. Since in his opinion no impartial jury could be found to judge the rebels, the British government would gain through clemency. And if in addition the imperial government would consent to compensate the innocent, it might even persuade French Canadians to forget the repression. The questions of amnesty and indemnity were to be the young Canadien leader’s priorities, and their settlement would be one of his principal achievements. Since several of his letters to Ellice on these matters are in Lord Durham’s papers, it is reasonable to suppose that his opinion may have influenced the partial amnesty proclaimed by the governor in 1838; again in 1842 it was he who took the first steps towards the final pardon of the exiles in 1845. He would obtain the nolle prosequi in favour of Papineau in July 1843; and finally he would propose in 1849 the famous Rebellion Losses Bill which marked his accession, amid drama and violence, to the summit of political power.

During the years 1837–38, La Fontaine’s political thinking was shaped. For him, “Canadiens have become British subjects by treaty. They must be treated as such.” As British subjects, French Canadians had a right to an assembly. The young politician therefore insisted that the legislature, suppressed in March 1838, should be restored. “Without it,” he wrote to Berthelot, “we will certainly become just like the Acadians,” legally incapable of reforming their institutions and influencing their destiny. As British subjects, French Canadians had the right in the assembly to exercise their preponderant and majority influence on the government. According to La Fontaine, if the Parti Canadien had been admitted to the governor’s council the disturbances would have been averted, and political and social harmony maintained. “It is a great mistake,” he wrote to Ellice, “to suppose that there is no means of rapprochement between the two parties. I do not hesitate to repeat what I have so often said, in Canada and in England, that it is easy to re-establish harmony among the majority in the two political parties, for their interests are the same. It is even a long felt need. Let local government in all its administrative and social dealings cease to make or to allow distinctions of race, let it advance openly towards a liberal but firm policy, let it abstain from favouritism towards the privileged classes. You will see harmony restored more quickly than one might think.” Indeed La Fontaine was convinced that it was through the union of the French and English of Lower Canada in a single party that the liberal transformation of institutions would be accomplished, to the best interests of the Canadiens and of Great Britain. The “political disturbances” were due to the government’s discriminatory practices and would therefore end with the complete application of the principles of the British constitution, according to which political distinctions were based on “opinions” rather than “origins.” The “bastard, unnatural government’’ before 1837 had encouraged Canadien leaders to look towards the republican institutions of the United States; in future “the soundest policy is to leave us no reason to envy them.” In stressing that “opinions” rather than ethnic “origins” were the basis of parties, La Fontaine, although unaware of it, shared the views of the Upper Canadian Reformer Francis Hincks*.

But in spring 1839, the Durham Report captured the attention of La Fontaine and of the Canadiens. The report defined the kind of government that La Fontaine had described in his letters to Ellice, a system in which the governor must undertake to follow the advice given by his Executive Council, which in turn would always be “responsible” to the elected house. Ministerial responsibility, applied to Lower Canada alone, would have meant that French Canadians would have predominated in the colony’s government. Hence La Fontaine could not do other than accept it. But, in conjunction with responsible government, Durham recommended the union of Upper and Lower Canada. This measure, much less acceptable to the “nationalists” of the two colonies, was anathema in Lower Canada. Almost all the political leaders, and especially Papineau, had fought it since 1822, and Lord Durham was clearly proposing it in 1839 with assimilation as its purpose. With his keen sense of realities, La Fontaine was able to see that union could help his people. It would lead to promising solutions to the colony’s economic and social problems, and in particular, through ministerial responsibility, provide the political instruments necessary for the reform of Lower Canadian institutions, which still reflected the absolutist and arbitrary structures of the old régime. He was therefore ready to agree to it. Twelve years later he recalled his decision: “after having carefully examined the rod by which it was intended to destroy my countrymen, I beseeched some of the most influential among them to permit me to use it, to save those whom it was unjustly designed to punish – to place my countrymen in a better position than they had occupied before. I saw that this measure enclosed in itself the means by which the people could obtain that control upon the Government to which they have a just claim.”

He needed courage, for in the months following the publication of the Durham Report Lower Canadians were hostile to the recommendations. Everything conspired to turn French Canadians against union: the provocative actions of Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson*, the offensive attitude of Upper Canadian members during the debate on union in the House of Assembly at Toronto, and, even more significant, the vital fact that the provisions of the bill adopted by the imperial parliament during the summer of 1840 did not recognize responsible government. La Fontaine summed up the principal objections to the act: “It is an act of injustice and despotism, in that it is imposed on us without our consent; in that it deprives Lower Canada of its legitimate number of representatives; in that it deprives us of the use of our language in the proceedings of our legislature, against the assurance of the treaties and the word of the governor general; in that it forces us to pay, without our consent, a debt we have not contracted; in that it permits the executive, under the guise of the civil list, and without the votes of the people’s representatives, to take illegally an enormous part of the country’s revenues.”

The principal leaders of opinion, journalists and politicians, and especially John Neilson* at Quebec and Denis-Benjamin Viger at Montreal, rejected union outright and fought for its repeal. “Finding ourselves alone,” La Fontaine recounted later, “we could not hide from ourselves the fact that it was impossible to arouse either the town or the countryside, so discouraged were they by events.”

On 25 Aug. 1840, less than ten days after it was learned that union had received royal sanction, La Fontaine published his “Adresse aux électeurs de Terrebonne,” in which he showed himself a realistic and adroit politician by making the following distinctions concerning the plan of union. Although some people reject it, he wrote, “does it follow that the representatives of Lower Canada . . . should commit themselves in advance and unconditionally to seek the repeal of Union? No, they ought not to do it. They should wait before deciding on a course whose immediate result would be perhaps to subject us again, for an indefinite time, to the liberticide legislation of a Special Council, and to leave us with no representation at all.” According to La Fontaine, union would allow a party to be set up on Reform principles rather than on nationality: “Reformers in the two provinces form an immense majority. . . . [Those of Upper Canada] must protest against provisions that subjugate their political interests and ours to the whims of the executive. If they failed to do so, they would place the Reformers of Lower Canada in a false position in relation to themselves, and would thus run the risk of delaying reform for many years. They, like us, would have to endure the inevitable discord with those who oppose them. Yet we share a common cause. It is in the interest of the Reformers of the two provinces to meet on the legislative level, in a spirit of peace, union, friendship, and fraternity. United action is more necessary than ever.” It was union also that would make possible the responsible government promised to Upper Canada but denied to Lower Canada. “For myself,” added La Fontaine, “I do not hesitate to say that I am in favour of the English principle of responsible government. I see in its operation the only possible guarantee of a good, constitutional, and effective government. The inhabitants of a colony must have control of their own affairs. They must direct all their efforts towards this end; and, to achieve it, the colonial administration must be formed and controlled by and with the majority of the people’s representatives.” The conclusion was clear. Union was the price that must be paid for responsible government, “the driving force of the English constitution,” and the means whereby French Canadians would regain all that the less acceptable recommendations of the report sought to take from them. It was also the indispensable condition for a transformation of institutions in an orderly manner, in peace and liberty, and with due regard for the parliamentary institutions to which French Canadians had become accustomed.

La Fontaine had discussed these ideas in his correspondence with Francis Hincks. Between 12 April 1839 and 30 Jan. 1840 the two Reformers had exchanged some ten letters in which they both expressed the view that a political party should be based on common principles rather than on interests of class or origin, and the conviction that together they could create such a party. The Toronto journalist knew he did not have sufficient support to get his plans for reform in Upper Canada accepted without the aid of the French Canadian representatives; La Fontaine knew that he needed the Upper Canadian influence to overcome both the conservative forces that were still strong in Lower Canada and the prejudices of London against his countrymen. On 17 June 1840 Hincks summed up his idea in a letter to La Fontaine: “Your countrymen would never obtain their rights in a Lower Canadian Legislature. You want our help as much as we do yours. . . . Our liberties cannot be secured but by the Union.” For La Fontaine there remained the task of convincing his compatriots.

He was ready. He was in great demand as a lawyer and had an extensive and influential clientele. He was considered to be a rich man. In 1840 he was sufficiently so to authorize Parisian friends to extend credit to Louis-Joseph Papineau. By then he and his partner Lewis Thomas Drummond* already owned a large block of houses and stores at the corner of Saint-Jacques and Saint-Lambert streets in Montreal, and two years later he purchased land on Rue Lagauchetière for £5,200. Furthermore, his activities during the rebellion had earned him the reputation of being pragmatic and resolute. And indeed he had the practical bent of those who solve difficulties easily. His correspondence reveals that he was able to distinguish the important from the secondary. He liked fine points of law, the precise data of a problem; he distrusted theory and valued neither philosophy, which he had never studied, nor fiction, nor poetry. He was not a thinker. In private life he was dour and uncommunicative, had few friends, seldom went out, and shunned social gatherings. In public life, he spoke dispassionately, without excess of emotion. In fact, it was his physical appearance that helped him command attention. Slightly above average height, he walked with a slow, measured tread. His black eyes, his calm, set expression gave him an air of self-assurance. Some thought him pretentious. He bore a striking resemblance to Napoleon, did his hair after the manner of the emperor, and adopted the habit of inserting the fingers of his right hand between the buttons of his jacket. It was said that he was ambitious. But he commanded the respect of all by his ability. The combination of ambition and doggedness made him capable of displaying extraordinary steadfastness and restraint; his difficult, cold nature invested him with an air of mystery which his supporters saw as disinterestedness.

La Fontaine devoted the next ten years of his life to attaining his goals. First, he had to get union accepted. A proven leader at 32, he had to manoeuvre adroitly among the old political hands. He knew the importance of not dividing politicians in a time of crisis, and therefore supported his elders in everything that was not contrary to his tactic of accepting union as a means of obtaining responsible government. He took part in meetings at Quebec and organized others at Montreal to protest the terms of union proposed by London. In April 1840 he clearly intimated his disapproval by refusing the post of solicitor general offered him by Governor Thomson. At the same time, he worked hard to get the ideas of his “Adresse . . .” accepted. After the first elections of the new régime had been announced, he worked to find candidates who would support him. In July 1840 he went to Toronto to meet his Upper Canadian allies, and in September received Hincks at his home in Montreal. He also went to Quebec several times to coordinate the efforts of Étienne Parent* and Morin in favour of union. His stand did riot always make him friends. When the polling stations were opened at Terrebonne in March 1841 he withdrew from the struggle, making way for Dr Michael McCulloch; the latter had the support not only of Governor Thomson’s followers but also of those Patriotes who sided with Neilson and Viger. Despite this personal setback, due as much to his desire to avoid compromising his leadership by an electoral defeat as to the fear that the presence of numerous braggarts in each camp would lead to violence, the election results throughout the province brought him a certain satisfaction. He had succeeded in convincing French Canadians to take part in the voting, and he could count on the backing of a good half-dozen members of the assembly. And his defeat at Terrebonne allowed him to test the spirit of solidarity of his allies.

Robert Baldwin*, leader of the party in Upper Canada, had been elected in two counties. On learning of La Fontaine’s defeat, he resigned his York seat and offered it to the Lower Canadian leader. La Fontaine was elected easily on 23 Sept. 1841, after spending three weeks among the Torontonians, accompanied by Étienne Parent. Ties of deep friendship linked him from then on with Baldwin. He was to consult him on all matters bearing on politics and the constitution and to tell him all the events of his personal life. The relationship lasted until Baldwin’s death in 1858. Apart from Joseph-Amable Berthelot, La Fontaine’s papers reveal no one else with whom he had such intimate personal relations.

Elected mla, La Fontaine continued his campaign in support of union in a more assured manner. At each by-election, he took steps to secure candidates favourable to his ideas. He won the confidence of several mlas who had been elected under Neilson’s banner. He also worked at making his message more widely known. In 1841 he offered advantageous terms to Ludger Duvernay to get him to return from exile and establish La Minerve again. This newspaper was to move quickly again to the forefront in the Montreal area, and was entirely devoted to La Fontaine’s interests. He also encouraged the founding of Le Journal de Québec, whose editor Joseph-Édouard Cauchon* always remained loyal to him.

In the summer of 1842, the political situation had become such that the new governor, Sir Charles Bagot*, realized he could no longer work with parliament without turning to La Fontaine. After two weeks of difficult negotiations, the young leader took the oath as attorney general for Canada East and head of the provincial administration. The date was 19 Sept. 1842. On his recommendation Augustin-Norbert Morin, Robert Baldwin, and Quebec lawyer Thomas Cushing Aylwin* also entered the government. A vote of 55 to five expressed the confidence of the assembly. Of the Lower Canadians, only John Neilson had voted in the negative.

La Fontaine was now in a position to prove that union could serve French Canadian interests. He set to work with a will. In less than a year he secured the repeal or amendment of the measures of the Sydenham régime that had most displeased French Canadians. He had the electoral law modified in order to establish a polling station in each parish, and thus diminish violence during elections. To increase French Canadian influence, he secured the adoption of a new electoral map of Canada East redrawn particularly in the areas of the Montreal and Quebec suburbs. He had the capital transferred from Kingston to Montreal, took the first of numerous steps to obtain amnesty for those condemned in 1837–38, and to restore the use of French as an official language in the records of the legislature and of the courts. La Fontaine paid particular attention to patronage. He knew that through it he could probably best demonstrate to his fellow countrymen that union could serve their interests. He gave important posts in the government to men like Étienne Parent and René-Édouard Caron*, clerk and president of the Executive and Legislative councils respectively. And he opened up careers and posts at all levels for all classes; the well-to-do he summoned to the Legislative Council, the modest habitant he had appointed land agent or census commissioner. “Patronage is power,” the Upper Canadian mla James Hervey Price* wrote to Baldwin on 6 Feb. 1843, and La Fontaine fully intended to show that French Canadians had arrived.

It was precisely on the question of patronage that he encountered the opposition of Governor Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*, who had replaced Sir Charles Bagot in March 1843. Metcalfe did not understand responsible government in the way that La Fontaine did. He refused to agree to follow the advice of the council and its leader, and when La Fontaine persisted, there developed in November 1843 what journalists of the day called “the Metcalfe crisis.” La Fontaine and his ministers, with the exception of the provincial secretary Dominick Daly, resigned en bloc. The house supported them, and the governor had to go in search of other councillors.

The years 1843 to 1847, when he was leader of the opposition, were La Fontaine’s most difficult. His health deteriorated and on several occasions he was forced to take to his bed for a week or two. At the end of November 1846 he had to undergo an operation to relieve his rheumatism, which left him weak for three months. In the summer of 1847 he went to Newport, R. I., to recuperate. In January 1848 he was again under medical treatment. During these same years Adèle La Fontaine too was quite ill. They also experienced the grief of losing their niece and adopted daughter, Corine Wilbrenner, who died on 4 Nov. 1844 at the age of 13. “You have children,” La Fontaine wrote at that time to Baldwin, “we have not. Corine was our adopted daughter. Her death will, I am afraid, exercise a great influence on my plans and calculations.”

In the political sphere, La Fontaine had to secure the loyalty of his own people without the use of patronage, and, after the defeat of the Reformers in the general election of 1844, without the hope of soon regaining it. In fact, the election results seemed to justify the views of those who had opposed the union of the Canadas and the union of the Reformers. Canada West returned a majority for Governor Metcalfe and the new government of William Henry Draper*. But Canada East elected 29 supporters of La Fontaine out of 42 members. Thus the partisans of the two groups were almost evenly divided, and two French Canadians, Denis-Benjamin Viger and Denis-Benjamin Papineau*, had joined the Executive Council in order to rally their countrymen to the governor’s side. They envisaged a loose collaboration with Canada West and resorted to the principle of double majority. This principle, which subsequently was more fully elaborated, favoured a temporary coalition of the majority in Canada East with the majority, no matter which party, in Canada West, to last as long as both were satisfied with the arrangement. La Fontaine opposed the principle in theory and in practice. For him ministerial solidarity was an essential condition of responsibility. And he was convinced that even if responsibility could theoretically be exercised without solidarity, Lord Metcalfe would never agree to commit himself to follow the directives of his council. Whatever theoreticians might argue about the principle, La Fontaine was right about Metcalfe. Moreover, neither the British prime minister, Sir Robert Peel, nor the colonial secretary, Lord Stanley, accepted the principle of responsible government for Canada. La Fontaine knew the concession would have to be wrung from them. “I know you think we shall never get Responsible Govt.” Hincks had written to him on 17 June 1840, “that the Ministry are deceiving us – granted – But we will make them give it whether they like it nor not.”

La Fontaine’s tactics were to keep the electors aware of his belief in responsible government. The challenge – in the event it was not met so successfully – was to avoid demagogy, violence, and compromise. By the end of 1843, La Fontaine began to identify responsible government with survival. It was not difficult for him to do so. Control of the executive by the spokesmen of the majority was in fact the best guarantee that French Canadian national institutions, threatened by the conclusions of the Durham Report, would be protected, as La Fontaine’s brief period in power in 1842 and 1843 had demonstrated. And to regain power, unity must absolutely be preserved. “What our countrymen must fear most in the present circumstances and at all times,” he announced as the heading for his programme for 1844, “is division. One cannot be too strongly persuaded of the great truth that union is strength. Let this word be, particularly at this moment, our rallying cry.” All must accept their mutual responsibility, and the “traitors” and “vendus” were those intent on dividing French Canadians. La Fontaine was clever. By taking the theme of unity, he was helping his party to benefit from the French Canadian habit of voting en bloc. In addition, he was using irony. The champion of British parliamentarianism and union, he was busy seeing that the label of vendu was pinned on the brother and the cousin of the principal nationalist of his generation. This theme, that la survivance could be achieved only by the united effort of all French Canadians voting together, has, or course, remained almost a cardinal tenet of Quebec nationalist ideology ever since.

La Fontaine’s political skill is also illustrated in his use of the language question. The proscription of French as an official language by the Act of Union had been one of the main points in the imperial policy of assimilation, and it was perhaps the one most resented by French Canadians. Realizing their concern, La Fontaine manoeuvred to identify his party’s cause with the question of language and thus gain for himself the full emotional allegiance of his followers. It is true that although the Act of Union gave no support to official use of French, French Canadians had come to realize that in their daily lives the law had little meaning. They continued to speak French, their schools taught it, their newspapers maintained it. Moreover if French had no official status at the seat of government, bilingual civil servants such as Étienne Parent imitated La Fontaine himself and wrote their reports in French, while such notables as the bishops of Quebec and Montreal corresponded with successive governors general and their secretaries in their own language. Several French Canadian politicians delivered their first speeches in parliament in French. And in 1844, at the opening of the second parliament of the union, Sir Charles Metcalfe reverted to the old Lower Canadian custom of having the clerk of the Legislative Council read a formal French translation of the speech from the throne. In 1844, however, La Fontaine, as leader of the opposition, began to raise the issue, making it, as his enemies averred, “a claptrap for popularity.”

His newspapers and his partisans accordingly began to refer to their leader’s first speech to the union parliament, in Kingston on 13 Sept. 1842. La Fontaine had begun in French and had been interrupted after a few sentences by a member who asked that he speak in English. After some reflection La Fontaine had grandly retorted: “Has he [the honourable member] already forgotten that I belong to that nationality which has been so horribly illtreated by the Act of Union? . . . He asks me to deliver in a language other than my maternal tongue the first speech I have to deliver in this house! I distrust my ability to speak the English language. But . . . even if I knew English as well as French, I would still make my first speech in the language of my French Canadian countrymen, if only to protest solemnly the cruel injustice of that part of the Act of Union which aims to proscribe the mother tongue of half the population of Canada. I owe it to my countrymen, I owe it to myself.” At the time the incident attracted little notice. But two years later La Fontaine’s propagandists saw to it that no Canadian elector would ever forget it. The leader of the opposition was to emphasize the language problem at every opportunity. Until the end of the decade he managed to manoeuvre almost every debate in the house onto grounds that turned a vote for his opponents into a vote against the French language. By mid 1848, La Fontaine had succeeded in identifying his party with the language issue – indeed, the new governor general, Lord Elgin [Bruce], complained that he spoke of nothing else. When he finally came to power he wished to inaugurate his government by proclaiming a new language policy. He did this by having Lord Elgin read the speech from the throne in French at the opening of parliament on 18 Jan. 1849.

No doubt La Fontaine was sincere. His public letters and his private official communications were always written in French. His reports as attorney general were bilingual, as were his letters of resignation as head of the government in 1843 and 1851 and his letter of thanks to Lord Elgin when he received his baronetcy. He gradually progressed towards nationalism, roved at first by party spirit (especially when he was again in opposition), and some years later by personal ambition. In his correspondence during 1837 and 1838, his “Adresse aux électeurs de Terrebonne,” and his exchanges with Hincks, he showed his concern to obtain reforms which would satisfy and serve the two Canadas. His analysis of the problems of French Canadians was in strictly political terms. But in 1854 he reached the point where he confused political and social with national concerns . . . and with his personal interests. When he accepted the title of baronet, he wrote Lord Elgin a letter in which such distinctions were indeed subdued: “I shall be the first French Canadian on whom this dignity has been conferred. I am equally the first, and in addition the only French Canadian to have been made attorney general and chief justice of my native country . . . . Rest assured, My Lord, that I can appreciate the motives which have prompted you to act on this occasion as on many others, the desire to prove to my countrymen of French origin that political and social inferiority is no longer their lot, and that all doors will be open to [them] as to their fellow citizens of other origins.” He seems however to have had some reservations about adopting nationalist stances. A few weeks after his resignation in 1851, when Le Journal de Québec was discussing an administrative question in a distinctly nationalist tone, he reminded Joseph-Édouard Cauchon of certain past rebukes. The latter replied: “I recall what you said to me with regard to the national question; but I replied to you that it was the only chord that could be struck successfully.” And La Fontaine, with his keen sense of reality, accepted the inevitable . . . and his hereditary title of baronet.

The same realism probably inspired him in the construction of his party’s electoral machine. He knew how elections were won. When in opposition, he set up a network of agents who could keep him informed at all times about the opinions, prejudices, needs, and desires in each county. At election times, these agents were readily transformed into speakers and candidates. Early in 1844, he asked Hincks to come to Montreal to coordinate operations. With the help of organizers such as Joseph-Édouard Cauchon for the Quebec region and George-Étienne Cartier* in Montreal, the Upper Canadian Reformer set up a team that was always ready, during brawls and riots, to cheer “good” candidates, besiege polling stations, and batter opponents. The team demonstrated its strength in a by-election in Montreal in April 1844, and, later, during the general elections of 1844 and 1847–48. It included French Canadians and Irishmen and created the atmosphere of a battlefield in the electoral struggles, especially in Montreal, where the Tories had previously won their greatest victories.

The team of French Canadians and Irish was also Catholic. Quietly, and perhaps inadvertently, La Fontaine found himself towards the end of his opposition years again at the head of a party that was increasingly seeking support from clerical circles. After 1843, his supporters had begun to improve their relationships with the clergy, who had gradually come to look upon politicians more favourably. Just as the latter needed clerical backing among the electors, the clergy for its part knew it must give up its old behaviour. Union had marked the end of the urbane, aristocratic approach through which the bishops of Quebec and the British governors had so carefully merged the interests of altar and throne. Now that real political power was slipping from the hands of the governor into those of the electors, the clergy had to begin to deal directly with electors and politicans, if it wanted the church to continue to exercise the influence that it genuinely believed to be its right. Politicians were therefore welcomed with increasing cordiality at the seminary and the bishop’s palace, and La Fontaine himself won the regard of the episcopate, particularly the new bishop of Montreal, Ignace Bourget*.

Despite early distrust, Bishop Bourget and La Fontaine were born to understand each other. Both were authoritarian and stern leaders, with the same stubborn character, the same profound sense of duty, and the same political skill. In 1845 and 1846 the debate about the bills on education and on the Jesuit estates led La Fontaine’s supporters and the clergy to form a lasting alliance. La Fontaine’s opposition ensured that the education act was satisfactory to the ultramontanes. The discussion on the Jesuit estates helped to enlarge the gap between the supporters of Denis-Benjamin Viger and the Papineau clan on the one hand, and those of the clerics and La Fontaine on the other. Following liberal doctrine Viger claimed the state had the right to dispose of the Jesuit estates as it thought fit; La Fontaine and his followers argued that these revenues belonged by right to the church. After 1846 the clergy was to prove one of the great social forces working for the principle of responsible government.

To what extent was this cooperation a moral compromise for La Fontaine? It is hard to say. When he was young he was reputed to be anticlerical. But at the same time he seems to have been faithful in his religious observances. At official dinners he made a large sign of the cross before sitting down; and he had been known to prostrate himself in the street before the Holy Sacrament, when it was being carried publicly for the communion of the sick. In 1855 he accepted the title of knight commander in the pontifical order of St Sylvester, which Bishop Bourget had recommended for him to Pius IX. But La Fontaine received this decoration with a touch of humour, which might suggest that his public demonstrations of religion were not wholly sincere. “For myself,” he confided to his friend, French historian Pierre Margry, “I cannot tell you to what I am to attribute my parchment and my two crosses, unless it is to my well-known piety, of which I can imagine you would never have had any idea.” At the time of his death in 1864, another friend, the devout Abbé Étienne-Michel Faillon, wrote to Margry: “That is how he died, after postponing from day to day his return to God . . . . He sacrificed himself for others, left few possessions; and despite all that, he did nothing for God and has appeared before Him empty-handed.”

Whatever his personal beliefs, as leader of the opposition La Fontaine was subjected to pressures from both opponents and supporters. He found himself gradually involved in an alliance with the church. He had wanted to break with the particularist and republican nationalism of the Patriotes, and in 1840 had denounced the dangers of an inward looking nationality. In 1848 he was once more at the head of a party to which he had given unity and a firm structure, but it too was moving towards a particularism quite as rigid as that of the republicans in the 1830s.

In the 1847–48 elections La Fontaine and his supporters won a resounding victory. He was elected in Montreal by a majority of 1,400 votes, and in Canada East as a whole his followers succeeded in 32 out of 40 counties. In Canada West, 23 Baldwinite Reformers were elected. The new governor, Lord Elgin, acknowledged that responsible government must finally be instituted. He agreed to entrust the government to the leader of the majority party in the house, and to undertake to follow his advice. Early in March 1848 La Fontaine was therefore sworn in as attorney general. He was the first Canadian to become prime minister, and the first French Canadian elected by his own people to direct their national aspirations.

In power again, La Fontaine took up the work that had been interrupted when he resigned in 1843. The Lower Canadian exiles were now back in the country; several of them had even come to thank him personally for his efforts on their behalf. There remained the indemnities to be paid to the victims of the soldiery of Sir John Colborne.

For La Fontaine, the Rebellion Losses Bill was no more than justice. It was designed as a broad, unstinting gesture that would finally put to rest the bitterness of 1837. But for many in Montreal’s commercial class, already suffering the trials of deep financial depression, and for many of the Tory politicians who had just lost political control of Lower Canada for the first time since 1791, the issue became a symbol. They reacted with the primitive, panic-stricken fury typical of the recently dispossessed. When Lord Elgin gave royal assent to the bill, a mob broke into the parliament building and set it afire. On the next day, 26 April 1849, the mob rushed to La Fontaine’s house, broke in, smashed woodwork and his costly period furniture, pulled off window sills and shutters, ripped up floors, and shattered china and glass. They set fire to the stables, burned several coaches, and pulled up a dozen saplings from the orchard. Later, in August, when some opponents of La Fontaine were arrested, the mob returned to the attorney general’s home. This time he was ready: the house was dark but a group of his friends including Étienne-Paschal Taché and Charles-Joseph Coursol* waited behind the shutters with guns. As the rabble moved towards the front door, shots rang out on both sides; before the rioters had fled, six were wounded, and one, William Mason, was dead. Rumours that La Fontaine would be assassinated filled the city. Twice he was assaulted on the street, and when he testified at the inquest into Mason’s death at the Hôtel Cyrus, it was set ablaze.

The riots of 1849 appeared to La Fontaine as a revealing counterpart of the rebellion ten years earlier. If not in lives lost, at least in national bitterness and property damage, the reaction of the Montreal Anglophones had several parallels with the “violence” of 1837–38. There was even a “rebellion losses” aftermath: La Fontaine’s supporters claimed damage for the destruction of their property: Morin £34, Francis Hincks £34, the Grey Nuns £65, and La Fontaine himself £716. They did not claim it from the provincial government, however, but from the municipal administration of Montreal, headed by Édouard-Raymond Fabre*, a political adversary of La Fontaine. But these outrages against his person and property only served to enhance the prestige of the prime minister.

During his tenure of office, from March 1848 to October 1851, La Fontaine entrusted Hincks with economic and commercial questions, and Baldwin with legal reform and with land utilization in Canada West. He retained responsibility for the courts and the distribution of patronage in Canada East. Hence, in the first session of the new parliament, he presented bills to institute the Court of Queen’s Bench, a court of appeal with four judges. In addition, he created the Superior Court as a court of original jurisdiction and a circuit court for small causes. Thus the broad outlines of judicial organization in Canada East were drawn in 1849–50.

In his administration of patronage, the prime minister utilized his network of agents and relied on the advice of his organizers, Caron, Cauchon, Cartier, and Drummond. He wanted to make certain that by a judicious allotment of favours all French Canadians would become permanently involved in self-rule. For two generations the Canadien professional class had been struggling to secure an outlet for its ambitions: now, with a kind of bacterial thoroughness, its members began to invade every vital organ of government, and assume hundreds of positions as judges, queen’s counsellors, justices of the peace, medical examiners, school inspectors, militia captains, postal clerks, mail conductors. And as the privileges and salaries of office percolated down to other classes of society, French Canadians came to realize that responsible government was no longer just an ideal. It was also a profitable fact. Henceforth, thanks to La Fontaine, all French Canadians would be guaranteed the possibility of room at the political top.

The prime minister did not escape setbacks. Three times, in 1849, 1850, and 1851, he put a bill before the house to increase the number of members for each section of the province from 42 to 75. He insisted that the representation of Canada East and West should remain equal, and he wanted the regions within each section to be equally represented. His bill never received the two-thirds majority required. In 1850 and 1851 La Fontaine was again in the minority over the clergy reserves and seigneurial tenure. On these questions he was absolutely determined to respect vested interests. He knew his ultramontane supporters feared that the secularizing movement prevalent in Canada West, especially with regard to the clergy reserves, would spread to Canada East. “As appetite grows the more it feeds on,” Drummond wrote to him about those who supported secularization in Canada West, “these hungry sectarians, after dividing up the clergy reserves, will perhaps not hesitate to lift a sacrilegious hand against the private properties of our religious communities.” Resolution of the question was, however, postponed.

As for seigneurial tenure, La Fontaine certainly favoured its reform, even its abolition. He had already proposed this in his “Adresse aux électeurs de Terrebonne” in 1840. But since then his alliances had led him in a conservative direction. He therefore insisted that the seigneurs should receive compensation. On 14 June 1850 he proposed in the house that a committee should be set up chaired by Drummond, with instructions to prepare a bill. The following year, when the committee proposed to redeem the rights of the seigneurs by forcing them to accept an amount fixed by the legislature, La Fontaine contended that such action would be confiscation. Finally he succeeded in getting this question postponed also; but meanwhile, on a point of order, he found himself in the minority among French Canadians for the first time since union. Only eight representatives voted with him, whereas his strongest allies, including Drummond, Cauchon, and Cartier, supported the majority.

His authoritarian temperament made it difficult for him to accept even this small setback. Hence he resolved to hand in his resignation. In any case, for some months he had been tired and sick. The dampness of winters in Toronto, which he had had to endure since the capital had been transferred to Canada West in 1850, had aggravated his rheumatism. He was overburdened with work and plagued by insomnia and headaches. On 6 March 1850, he had written to Joseph-Amable Berthelot to say that if paradise was in store for those who had experienced only tribulation in this life, he would most surely obtain his passport. In November 1850 he confided to Lord Elgin that he was weary of public life. Then, during the winter of 1851, his wife also began to complain of rheumatism. The resignations of Baldwin on 27 June 1851, and of Hincks on 15 September, profoundly distressed him. On 26 Sept. 1851, after one last meeting of the Executive Council, held at Niagara Falls, he handed his own resignation to Lord Elgin.

He had attained all the objectives he had set himself in the years 1837–40. Union had been accepted; the rebels had been pardoned and the victims compensated; responsible government had been secured. He had established the structures which would enable Jean-Baptiste Meilleur* to undertake the reform of education, Morin to bring about the transformation of the seigneurial régime and make the Legislative Council an elective body, and the clergy to further their efforts of colonization. He had succeeded in stimulating and coordinating the activity of his colleagues. And his greatest success had been to give expression through the institutions of the country to the social aspirations of the liberal bourgeoisie.

In Montreal, La Fontaine returned to the practice of law with his former partner Joseph-Amable Berthelot. His reputation as a logical, firm, and precise speaker preceded him in the courts, where law students and young lawyers often went to hear him argue. His coolness and self-control were much admired: he persuaded by force of ideas rather than by sonorous periods or brilliant words. His influence also extended to business circles. At the time of the great fire in Montreal in 1852, it was he who was chosen by the city council to negotiate a loan. Then, on 13 Aug. 1853, after the death of Sir James Stuart*, he was appointed chief justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench, the tribunal which he had reorganized in 1849. He sat there for the first time on 1 July 1854.

Throughout the final decade of his life La Fontaine was burdened by illness. “At 40, one is still young,” he wrote to Pierre Margry on 4 Nov. 1859; “at 52, with health daily undermined by too sedentary a life that has already ruined the strongest constitution a poor mortal was ever privileged to possess, one perceives that the years are numbered.” His hair had gone white, and he was becoming fat. In the early 1860s his corpulence had become distressing for him.

He travelled to recover his health. For nearly a year, from the summer of 1853 to the spring of 1854, he made the “grand tour,” stopping in London, where he stayed with Lord Elgin, in Florence, and in Rome, where he was received in audience by Pius IX. He spent several months in Paris and visited museums and art galleries. It was during this stay that his resemblance to Napoleon I sent a stir of excitement through the old soldiers at the Invalides. It was also on this voyage that he had become a friend of the historian Pierre Margry, a regular and interesting correspondent. In 1862–63 he spent a further ten months in Paris for medical treatment; he was accompanied by his brother-in-law, Charles-François-Calixte Morrison, parish priest of Napierville. Meanwhile, in 1855, 1856, 1857, and 1859 he had been obliged to take to his bed following attacks of rheumatism, “an unpleasant companion who persists in visiting me.” But Lady La Fontaine had died before him. On 27 May 1859, at the age of 46, she passed away after a long illness.

On 30 Jan. 1861, he remarried at Montreal; his second wife was Julie-Élisabeth-Geneviève (Jane) Morrison, 39 years old, widow of Thomas Kinton, an officer in the Royal Engineers, and mother of three girls aged ten, eight, and six. She came originally from Maskinongé and was descended from the first Bouchers. La Fontaine, who had taken an interest in genealogy since his retirement from public life, wrote to Margry: “Thus, she and I have a common ancestor.” The new Lady La Fontaine nursed her husband during his last years: he spoke of her as his “sister of charity.” She also gave him the joy of fatherhood. A son, Louis-Hippolyte, was born on 11 July 1862.

Called upon to preside over the special tribunal of 13 judges set up in 1855 to rule on the claims resulting from the 1854 act on seigneurial tenure, La Fontaine became engrossed in the history of the feudal system and of civil law in Canada. He cherished the hope of publishing a scholarly study of the customs of New France and Lower Canada. His correspondence reveals his numerous contacts with genealogists and archivists in France, England, and Canada. “Again and again I go through the registers of the parishes at Quebec, Montreal, and 3 Rivières,” he wrote to Margry on 4 Nov. 1859. He was thoroughly tired of politics. In 1853 he was already showing signs of this disenchantment. When visiting Florence he had met the painter Napoléon Bourassa*. “Your leaving politics,” the young man is said to have remarked, “must have provoked a deep commotion in our country?” “As for reaction, my young friend,” La Fontaine had replied, “I saw only that of the people who rushed forward to take my place.” He began to associate with such historians and men of letters as Abbé Faillon, Jacques Viger*, Georges-Barthélemi Faribault, and François-Xavier Garneau. In 1859 he published an essay on slavery in Canada, and, between 1860 and 1864, several unsigned articles on genealogy. He contributed regularly to La Minerve and to the Annales of the Société Historique de Montréal. However, his history of law was never completed.

On 25 Feb. 1864 La Fontaine had an apoplectic fit in the judges’ chambers. He was taken home, where he gathered his son in his arms, made the sign of the cross, and lost consciousness. He received extreme unction from the vicar general, Alexis-Frédéric Truteau*, and died during the night. At his funeral, presided over by Bishop Bourget, 12,000 persons gathered. Lady La Fontaine gave birth to a second son on 15 July, but he died in 1865; his elder brother, Louis-Hippolyte, followed him to the grave in 1867. Lady La Fontaine lived until 1905.

For French Canadians, La Fontaine’s accomplishments put an end to the period of the sterile nationalist claims of the Papineau type. His work opened up new directions in the areas of administration, law, education, settlement, and politics. It was proof of the power of national unity and of cooperation among those whom history and geography had brought together. Despite the Act of Union, which was clearly directed against French Canadians, La Fontaine was able to demonstrate that cultural survival depended not on constitutional documents but first and foremost on the collective will to live and on enthusiasm engendered by reform. Convinced of the interdependence of the two Canadas, and refusing to follow those who in his opinion failed to understand true grandeur, he transmitted to future generations through his accomplishments his confidence that their cultural fulfilment was linked to the vitality and flexibility of the parliamentary system of Great Britain. Thanks to him, a great and new hope was born.

By his decision to use British principles to strengthen his own nationality, La Fontaine did more than ensure the cultural survival of French Canadians. He also became one of the founders of the future Commonwealth of Nations. For within a century after the French Canadians solved their national problem by political evolution rather than armed revolt, other peoples on continents the Canadians of the 1830s and 1840s had barely heard of made use of the same pattern to achieve their own cultural destinies, and, like the French Canadians, managed not only to gain their collective freedom according to their masters’ own principles but also to accede in peace to ruling their rulers. Thus the practice of La Fontaine’s own life – radical nationalism, imprisonment for rebellion, shift to moderation, and the first prime ministership of a newly self-governing nation – became, a century later, the classic pattern of colonial leaders in most parts of the commonwealth.

For the tradition of Canada as a whole his lasting contribution is obvious as well: he is the father of parliamentary democracy on this continent; or, as he himself expressed it in the play on his name which he officially chose as a motto when he was created a baronet: Fons et origo.

A strange man he was: stubborn, introverted, pragmatic, ambitious; a man of few friends, who loved his country, not with wild passion, but with a devotion hard and steady. He was difficult to love, but he made it much more difficult not to admire him.

[The most important primary material on Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine is found in the La Fontaine collection at the Bibliothèque nationale du Québec (Montréal), in the Robert Baldwin papers at the MTCL, and in the Henry Vignaud papers at the William L. Clements Library (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor); the latter includes his letters to Pierre Margry.

Other archival collections include significant items for La Fontaine’s life and work: at the PAC, the governors’ correspondence (MG 24, A), especially the Elgin-Grey papers (MG 24, A10, 21–37); at ANQ-Q, the Collection Papineau and the Langevin papers (AP–G–134); at the AAQ and the ACAM, the correspondence of bishops Signay, Lartigue, and Bourget. In addition, contemporary newspapers contain a great deal of information on La Fontaine’s activities.

La Fontaine was the author of Les deux girouettes, ou l’hypocrisie démasquée (Montréal, 1834); Notes sur l’inamovibilité des curés dans le Bas-Canada (Montréal, 1837); Analyse de l’ordonnance du Conseil spécial sur les bureaux d’hypothèques . . . (Montréal, [1842?]); and with Jacques Viger, De l’esclavage en Canada (Montréal, 1859).

Biographies of La Fontaine by L.-O. David, Sir Ls. H. Lafontaine (Montréal, 1872), by A.-D. De Celles, Lafontaine et son temps (Montréal, 1907), and by S. B. Leacock, Baldwin, Lafontaine, Hincks; responsible government (Toronto, 1907), have been superseded by the more recent works by W. G. Ormsby, The emergence of the federal concept in Canada, 1839–1845 (Toronto, 1969), by [M.] E. [Abbott] Nish, “Double majority: concept, practice and negotiations, 1840–1848” (unpublished ma thesis, McGill University, Montreal, 1966), and by Jacques Monet, Last cannon shot. The Last cannon shot includes a more detailed bibliography for Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine. j.m.]

Correspondence between the Hon. W. H. Draper and the Hon. R. E. Caron; and, between the Hon. R. E. Caron and the Honbles. L. H. Lafontaine and A. N. Morin . . . (Montreal, 1846). Hommages à La Fontaine; recueil des discours prononcés au dévoilement du monument de sir Louis Hippolyte La Fontaine en septembre 1930 . . . , Clarence Hogue, édit. (Montréal, 1931). Lettres à Pierre Margry de 1844 à 1886 (Papineau, Lafontaine, Faillon, Leprohon et autres), L.-P. Cormier, édit. (Québec, 1968), 13–55). Catalogue de la bibliothèque de feu sir L. H. Lafontaine baronnet, juge en chef, etc. . . . (Montréal, [1864?]). Réjane Soucy, “Bio-bibliographie de sir Louis-Hippolite Lafontaine, bart.” (thèse de bibliothéconomie, université de Montréal, 1947). Olivier Maurault, “Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine à travers ses lettres à Amable Berthelot,” Cahiers des Dix, 19 (1954), 129–60.

Jacques Monet, “LA FONTAINE (Ménard, dit La Fontaine), Sir LOUIS-HIPPOLYTE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/la_fontaine_louis_hippolyte_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/la_fontaine_louis_hippolyte_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques Monet |

| Title of Article: | LA FONTAINE (Ménard, dit La Fontaine), Sir LOUIS-HIPPOLYTE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |