Source: Link

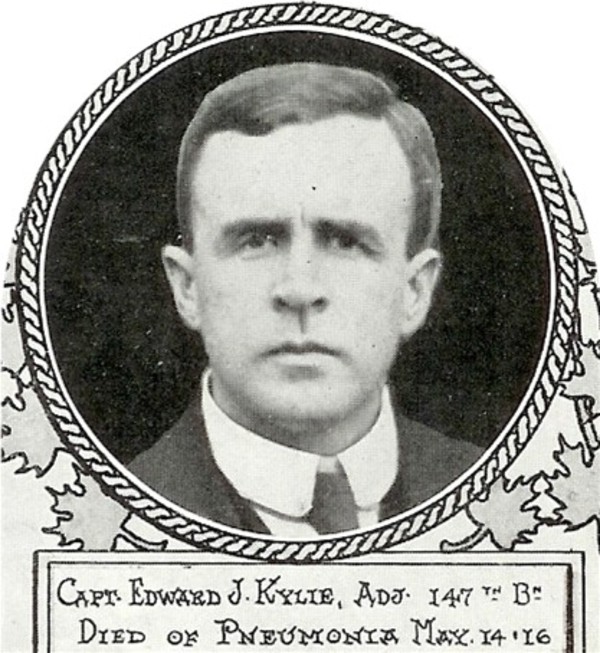

KYLIE, EDWARD JOSEPH, professor, historian, and army officer; b. 19 Sept. 1880 in Lindsay, Ont., only child of Richard Kylie, a blacksmith, and Norah Regan; d. unmarried 14 May 1916 in Owen Sound, Ont., and was buried in Lindsay.

Richard and Norah Kylie provided their son with the best education available in Lindsay: at home, at the Loretto sisters’ school, and at Lindsay Collegiate Institute. They then sent him on scholarship, in 1897, to University College at the University of Toronto. In 1901 he graduated with a ba, having studied classics, English, and history, engaged in student politics, and edited the student newspaper the Varsity. George MacKinnon Wrong*, an Anglican clergyman and chairman of the department of history, which had been established in 1895, recognized his promise and sent him to Balliol College in Oxford, supported by the Flavelle Travelling Fellowship. There Edward Kylie read modern history, obtaining a first in 1904 and an ma in 1906, and again he made his mark in extracurricular affairs: in 1903 he became the first colonial to be elected president of the Oxford Debating Union.

Oxford, particularly its tutorial system, whose virtues he urged on Wrong in 1903, and the sense of being at the heart of the British empire, marked Kylie for the rest of his life. The experience also made him an ideal candidate for Wrong’s first appointment to his department, in 1904, though his rank and salary were settled only after protracted meetings between benefactor Joseph Wesley Flavelle*, university president James Loudon, and provincial education minister Richard Harcourt*. One colleague thought Kylie had returned home “over-refined and sterile.” Kylie’s quick intelligence, charm, and youthful enthusiasm, however, won over any who might have wondered at Wrong’s decision to award the history lectureship to a Roman Catholic in sternly Protestant Toronto. He immediately gained the students’ favour; he served as honorary president of University College’s Literary and Scientific Society in 1905–6 and, the following term, of the Undergraduate Union. By 1912 he had become an associate professor.

Kylie shared his chairman’s ambitions for the department and his vision of Canada’s place in the empire. He divided his scholarly energy between medieval England, publishing The English correspondence of Saint Boniface . . . (London, 1911), and 19th-century Canada, contributing a section on the constitutional development of the united Canadas between 1840 and 1867 to the series called Canada and its provinces. Kylie’s thorough, if unoriginal Whiggish account of these pre-confederation years emphasized the peaceful achievement of responsible government as the key to both Canadian and imperial governments.

Kylie was devoted to undergraduate teaching, especially to Wrong’s modified tutorial system: small groups rather than Oxford’s one-to-one discussions were the best that Toronto could afford. Wrong’s Historical Club – Kylie spoke about the role of the Great Powers in North Africa at its first meeting in 1905 – won his enthusiastic support. This self-selected group of about 25 male students from various disciplines met at the homes of Toronto’s élite to debate the problems of the world. Through the club, members not only sharpened their wits but also developed reputations and networks.

Wrong generously brought Kylie into his own carefully established network. The ambitious young historian soon began to move in influential circles and to appear in public print and on the public platform. In 1909 he addressed the prestigious Empire Club of Canada in Toronto on “The menace of socialism.” His proposed antidote was borrowed from Andrew Carnegie’s “Gospel of wealth”: profit sharing, free education, and a heightened sense of public duty. Nothing there upset the appetites of the local politicians, clergymen, and business leaders attending the luncheon. Kylie’s firm belief in the “responsibility of the individual to the community” would later lead him to involvement in the Toronto Housing Company Limited, a private enterprise that, under the management of urban reformer George Frank Beer, attempted to provide inexpensive rental units.

But it was international affairs that preoccupied Kylie in the years of crisis before World War I. In “The problem of empire,” published in the Canadian Courier in 1907, he worried about changes that threatened to undermine Canada’s British heritage. Only “urgent national duties and concerns” would elevate a materialistic citizenry and their leaders above the quarrels, the corruption, and the pursuit of “private gain” that deadened the country’s spirit.

The solution for Kylie, as for Wrong and such Toronto leaders as Flavelle, banker Byron Edmund Walker*, and journalist John Stephen Willison*, was a reorganization of the empire that would strengthen it and provide Canada with greater influence. Beginning in 1908 and more intensely as the Anglo-German naval competition heated up, Kylie joined in what had become known as the Round Table movement, formed to promote the idea of imperial unity that had emerged from efforts to unify South Africa after the war of 1899–1902. As a member and a secretary of the Canadian branch, Kylie participated in regular private discussions, travelled the country speaking and sounding out opinion, and wrote about Canadian affairs for the movement’s journal, the Round Table. In this debate the past provided a guide. Responsible government and confederation, he wrote in Canada and its provinces in 1913, “have resulted directly in the development of what we now describe as colonial nationalities. They have demonstrated, at the same time, that the Briton beyond the seas can find an outlet for his political aspirations within the corners of the Empire.”

This enthusiasm for the empire and Canada’s place in it ensured that Kylie would view the outbreak of war in August 1914 as an opportunity for both imperial cooperation and personal service. During 1914–15 he organized E Company of the university-based Canadian Officers’ Training Corps and acted as a recruiting officer at the university for Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. His friend and fellow University College graduate George Franklin McFarland became commanding officer of the 147th Infantry Battalion, organized in Grey County in November 1915. Kylie joined it then as adjutant, with the rank of captain, and began his training at Owen Sound. Inoculated for typhoid in May 1916, he contracted the disease and developed pleurisy and lung congestion. Despite the arrival of two medical specialists from Toronto and a new supply of oxygen in a car driven by Major Charles Vincent Massey*, another Wrong protégé and Balliol man, Kylie died on 14 May at age 35. Survived by his parents, he was buried with military honours in his home town, a special train having been chartered to carry mourners from Toronto.

The Edward Kylie memorial fellowship, established by a committee chaired by Massey, ensured that others from the University of Toronto could follow Kylie’s path to Oxford for historical studies.

Kylie’s chapter on “Constitutional development, 1840–1867” appears in Canada and its provinces; a history of the Canadian people and their institutions . . . , ed. Adam Shortt and A. G. Doughty (23v., Toronto, 1913–17), 5: 105–62. His address on “The menace of socialism” was printed in Empire Club of Canada, Speeches (Toronto), 6 (1908–9): 120–28, and “The problem of empire” is in the Canadian Courier (Toronto), 11 May 1907: 14.

AO, RG 80-2-0-152, no.33497. Univ. of Toronto Library, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, ms coll. 1 (B. E. Walker papers); ms coll. 36 (G. M. Wrong papers). Daily Mail and Empire, 15 May 1916. Globe, 15 May 1916. Lindsay Post (Lindsay, Ont.), 19 May 1916. Watchman-Warder (Lindsay), 18 May 1916. Claude Bissell, The young Vincent Massey (Toronto, 1981). Michael Bliss, A Canadian millionaire: the life and business times of Sir Joseph Flavelle, bart., 1858–1939 (Toronto, 1978). Robert Bothwell, Laying the foundation: a century of history at University of Toronto (Toronto, 1991). James Eayrs, “The Round Table movement in Canada, 1909–1920,” CHR, 38 (1957): 1–20. Carroll Quigley, “The Round Table groups in Canada, 1908–38,” CHR, 43 (1962): 204–24. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. Univ. of Toronto, University of Toronto roll of service, 1914–1918 (Toronto, 1921).

Ramsay Cook, “KYLIE, EDWARD JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kylie_edward_joseph_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kylie_edward_joseph_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ramsay Cook |

| Title of Article: | KYLIE, EDWARD JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |