Source: Link

KING, WILLIAM HENRY, schoolteacher, homoeopathic physician, and convicted murderer; b. November 1833 in Sophiasburg Township, Upper Canada, eldest son of George King and Henrietta —; m. 31 Jan. 1854 Sarah Ann Lawson of Brighton Township, Upper Canada, and they had one child, who died in infancy; d. 9 June 1859 in Cobourg, Upper Canada.

William Henry King, who from childhood “gave evidence of a very intellectual and persevering turn of mind,” was sent to school in Sophiasburg at the age of five. His progress was so pronounced that the following year he was taken by his teacher to other schools “on exhibition days to speak pieces on the stage.” In 1844 the family settled in Cramahe Township where William’s father soon amassed “a considerable amount of property” and became “independent.” After the 1851 harvest, William went to the Normal School in Toronto, which he attended during the winter months of the next two years. Married early in 1854, King moved to Toronto where he and his wife took in boarders while he studied for his first-class teaching certificate. After he obtained the certificate, they moved to Hamilton, again taking in boarders, and William taught school and began the study of homoeopathic medicine with a local doctor. In the fall of 1856 King entered the Homoeopathic Medical College of Pennsylvania (Hahnemann Medical College and Hospital of Philadelphia), from which he received his diploma early in March 1858, and on St Patrick’s Day he set up a practice in the small community of Brighton. His income was soon about $200 a month and he felt that he was “in a fair way to acquire both fame and wealth.”

King’s professional ascendancy was, however, offset by personal unhappiness. Three months after his marriage, he claimed, he had discovered that his wife “was not the virgin I married her for.” Shortly thereafter his wife, now pregnant, accused her husband of “misusing” her and returned to her parents; during this time King wrote a number of letters accusing her of infidelity, for which he later apologized. Early in 1855 their child was born (to whom “it is said that he manifested much dislike”) but it was to live only about a month. During King’s stays in Philadelphia in 1856–57 and 1857–58, his wife had again removed to her parents’ farm. It is perhaps not surprising that domestic tranquillity did not await him on his arrival in Brighton in the early spring of 1858.

Shortly after his return, King became involved with one of his patients, Dorcas Garrett. This relationship ended abruptly in the early summer when Miss Garrett threatened to make public a letter from King which entreated her not to marry too quickly since his wife was ill and would probably die. The doctor later claimed to have been ashamed of himself. His wife became pregnant again in June but that fall a further temptation entered his life. On 23 September he met Melinda Freeland Vandervoort, “a young lady of about 20 years, . . . well educated, of a rather . . . coquettish turn, though not what would be called handsome.” She had apparently fallen in love with a photograph of King on a visit to his house and he was “completely intoxicated” by the beauty of her singing voice. They exchanged puerile love letters: one of his, addressed to “Sweet little lump of good nature” on 10 October, claimed that his wife was very ill. Four days later his wife “took sick.” She suffered severely from vomiting until her death on 4 November. Despite the protestations of her parents, who attended her throughout most of the ordeal, King had resisted calling in other doctors when her condition did not improve. He had diagnosed her problem as ulceration of the womb and prayed that the medicine which he frequently administered, and always prepared in the privacy of his office, would “have its desired effect.” On his wife’s death he underwent “a paroxysm of grief’ which was repeated at the funeral. None the less, by 8 November he was back to his practice, no doubt with an eye to the future and Miss Vandervoort. On returning from a professional visit that evening, however, his dreams were shattered. Before her daughter’s death, his mother-in-law had found a likeness of Miss Vandervoort in the doctor’s coat as well as some damaging correspondence, and the Lawson family had become suspicious. A coroner’s inquest had been ordered and King was informed by his father-in-law that it was indeed in session at that very moment. The doctor panicked. He travelled immediately to the Vandervoort farm, persuaded Melinda to flee with him, and made for the border. Four days later he was apprehended by his brother-in-law and an American marshal near Cape Vincent, N.Y., and returned for trial.

On 4 April 1859 the “Wife Poisoning Case” opened in the court-house just north of Cobourg. It was estimated that “not less then fifteen hundred” had come to hear the trial and the court-room, which could “accomodate about four hundred, was filled to excess.” Confident of acquittal during his incarceration, King, a man of “about 5 feet 11 inches, of a pale countenance, dark hair, with sandy whiskers, [and with] a small dark penetrating eye . . . that would seem to penetrate into the mind of his man,” strode into the dock giving an impression that “much more bespoke a city gentleman than one who was about to be tried for the murder of his wife.” The trial was heard before Judge Robert Easton Burns*; the chief crown counsel was Thomas Galt and the defence was headed by John Hillyard Cameron*. The crown established a solid case for arsenic poisoning, aided by the expert testimony of Henry Holmes Croft*, a professor of chemistry at the University of Toronto, and King’s letter to Melinda as well as his actions upon hearing of the inquest sealed his fate. Nevertheless, when on the morning of 6 April the foreman of the jury pronounced him guilty, with a strong recommendation for mercy, the doctor “did not appear to have expected the verdict.” Three days later King listened with composure as Burns sentenced him to be hanged on 9 June, but seconds after the judge had finished King’s “lip quivered, and burying his face in his handkerchief he wept convulsively.”

During his confinement while awaiting execution, King divided his time between prayers for salvation and tearful self-pity. He was visited by a steady procession of clergymen who prayed with him and also kept him informed as to the progress of his appeals for clemency. After all hope of commutation had vanished, King decided to confess. Later described as “a curious combination of self-revelation and sickening sentimentality,” the confession, which blames early marriage, lust, his wife’s infidelity, the devil, and just about everything possible save himself, was sent to the Toronto Globe for publication in May. The editor felt that this self-serving document was “abominable” and refused to print it. King, though offended, went on in pursuit of redemption and in the last days seemed convinced of his salvation.

As the execution approached, the Cobourg Star attempted to dissuade its readers from contributing to a public spectacle on the appointed day, wondering “that the boasted civilization of the nineteenth century has not taken away the opportunity of indulging such an unhealthy, such a prurient curiosity.” None the less, a crowd estimated at between 5,000 and 10,000 gathered before the gallows on the morning of 9 June. King “ascended the ladder . . . with a very firm step,” though “his face bore the mark of recent tears.” He read his prepared address in a clear voice and was praying fervently when the drop fell and he was “launched into eternity.” The Victorian civility of the crowd, which maintained “a respectful deportment befitting the solemnity of the occasion,” was balanced by the fact that the rope was cut into pieces and distributed among certain interested persons. The appearance of polite reverence effectively masked the atmosphere of vengeance. Years later Edwin Clarence Guillet*, who inherited one of the pieces of rope, could observe: “Altogether, no one could want a better execution.”

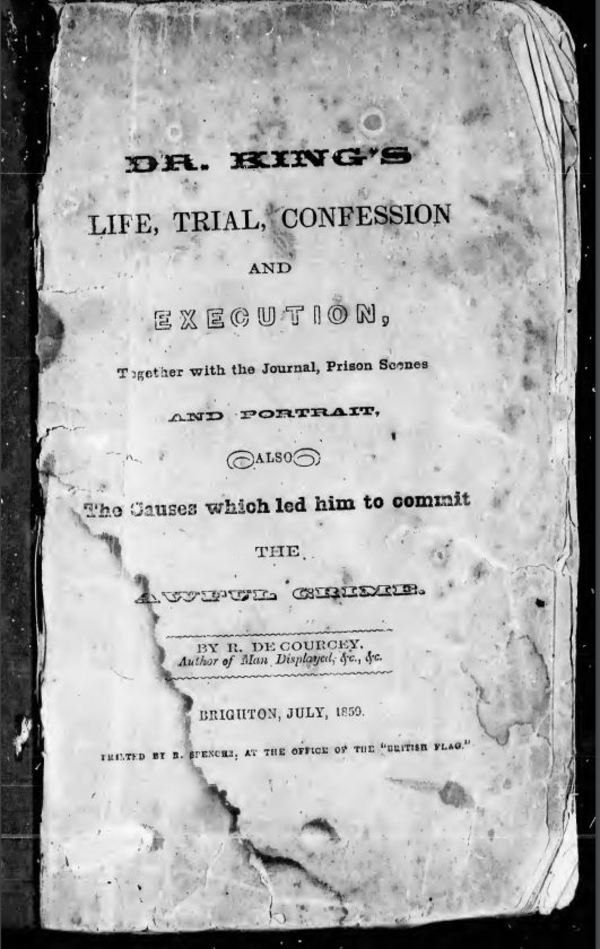

[Contemporary interest in King’s case is indicated by almost verbatim accounts of the trial in the Cobourg Star and the Toronto Globe as well as by the publication in 1859 of at least four pamphlets containing the Globe reports along with information on King’s life, imprisonment, and execution. The earliest of these pamphlets, written by R. De Courcey and shown to King for verification before his death, no longer survives. A second and fuller account by De Courcey, Dr. King’s life, trial, confession and execution, together with the journal, prison scenes and portrait, also the causes which led him to commit the awful crime, was published in Brighton, [Ont.], in July 1859. The journal referred to was kept between 14 April and 9 June by Alexander Stewart, the special constable assigned to guard King until his execution. Stewart is thought to be the author of The life and trial of Wm. H. King, M.D., for poisoning his wife at Brighton (Orono, [Ont.], 1859), which contains the material found in De Courcey plus an account of the inquest. The fourth pamphlet, Trial of Dr. W. H. King, for the murder of his wife, at the Cobourg assizes, April 4th, 1859, with a short history of the murderer (Toronto, 1859), is a reprint of the Globe’s account of the trial with a summary of the addresses of counsel, not found in the other pamphlets. In 1943 E. C. Guillet wrote “The strange case of Dr. King; a study of the evidence in The Queen versus William Henry King, 1859,” based on the above material, as the second volume in his “Famous Canadian trials” (50v., 1943–49). Only the first volume was published; the entire series is available in manuscript at York Univ. Arch. (Toronto), and five typescript copies were produced for distribution to major North American libraries, including MTL and the Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library at the University of Toronto. c.d.]

PAC, RG 31, A1, 1851, Brighton Township. Cobourg Star, 6, 13 April, 18 May, 8, 15 June 1859. Globe, 6–8, 14, 23 April, 24, 25 May, 10 June 1859. Marriage notices of Ontario, comp. W. D. Reid (Lambertville, N.J., 1980). E. C. Guillet, Cobourg, 1798–1948 (Oshawa, Ont., 1948).

Charles Dougall, “KING, WILLIAM HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/king_william_henry_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/king_william_henry_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Charles Dougall |

| Title of Article: | KING, WILLIAM HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |