Source: Link

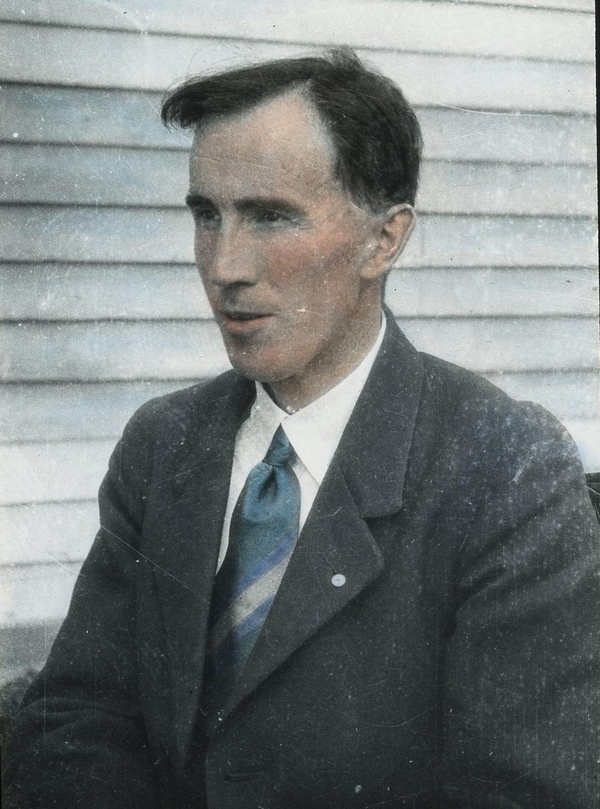

JACKSON, OLIVER, Methodist and United Church clergyman, educator, editor, author, and social reformer; b. 18 July 1887 in Abergavenny, Wales, son of George Jackson and Melinda Lythe; m. 24 July 1918 Rosalie Noseworthy in Clarke’s Beach, Nfld, and they had three sons and one daughter; d. 3 Nov. 1937 at sea off the southwest coast of Nfld.

After acting as a Methodist lay preacher in his native Wales, Oliver Jackson volunteered in 1911 for service in Newfoundland and became a probationer of the Newfoundland Conference of the Methodist Church of Canada. He was stationed from 1911 to 1913 in Campbellton, and from 1913 to 1915 in Clarke’s Beach. At the latter post he met his future father-in-law, Frank Noseworthy, a general dealer and Methodist layman. Noseworthy represented to Jackson the ideal of a contemporary member of his church, and he likely served as a role model to the young probationer, as he had been to other aspiring ministers. Writing his obituary in December 1929, Jackson stated that his father-in-law “was not afraid of emotion but guarded against excitement” and that the anchor of his faith, his love of Jesus, had been “first ethical and then merciful.” He also admired the fact that Noseworthy’s “ethic of the gospel” had been “brought to bear on the lives and relationships of others,” and a selfless commitment to service would become Jackson’s own trademark.

In 1915 the Newfoundland conference recommended Jackson for further education in arts and theology at Wesleyan Theological College in Montreal [see George Douglas*], which was affiliated with McGill University. He studied there until 1918, and at the 50th anniversary celebrations of the college five years later he and two other Newfoundland ministers would receive their bachelor of divinity degrees. Upon his ordination on 3 July 1918 at Gower Street Methodist Church in St John’s, he was admitted to full connection with the Newfoundland conference.

Jackson’s first posting was to Brigus, where he remained until 1923, and from 1921 Cupids was also listed as his charge. He served the pastorate of Freshwater, Conception Bay, from 1923 to 1928, during which time the Methodist Church became part of the United Church of Canada [see Samuel Dwight Chown], and he was responsible for Bell Island and Portugal Cove from 1928 to 1931. Beginning in 1919 Jackson served the conference for several years as an examiner of probationers in sociology; in addition, he chaired numerous committees and held various offices, such as conference treasurer and district secretary for religious education. After Mark Fenwick retired in 1931 as the conference’s superintendent of missions, Jackson succeeded him, relocating to St John’s. He would retain this position, along with that of field secretary of Christian education, until his death in 1937.

As superintendent of missions Jackson travelled indefatigably by boat, making known the religious and social conditions of the country in numerous realistic accounts that were published in the conference’s periodical, the Monthly Greeting, under the title “The superintendent’s log.” In his description of one of these trips he matter-of-factly observes: “The men I met going into the woods today seemed very poor; the children in the settlement are not robust or warmly clad and the women look too old for their years. The families go from [one] job to another but do not see a dollar in cash. Wages are low and prices generally high. If anything is left over after the accounts are squared, it has to be left on the merchant’s books to be taken up over his counter and no one else’s.”

In June 1932 Jackson became editor-in-chief of the Monthly Greeting, replacing the long-serving Levi Curtis. With Jackson’s arrival the entire staff of the periodical changed, as did its editorial policies and outlook. He sought to increase local-news content and raise social issues that pertained to Newfoundland and its United Church congregations. His theological indebtedness to Walter Rauschenbusch and the American Social Gospel movement was made explicit in 1934 when he serialized a selection of prayers from Rauschenbusch’s For God and the people: prayers of the social awakening (Boston, 1909) on the cover of the Monthly Greeting.

Jackson had a deep concern for people who were facing dire hardships during the Great Depression. He saw education, self-sufficiency, and economic independence as solutions that would lead to a general betterment of the living conditions of ordinary Newfoundlanders. It was Jackson’s love for the common people, as well as his fear that further deprivation might have serious social consequences, that led him to criticize the truck system, which had resulted in their endemic indebtedness to local merchants. “How has it come to pass in Newfoundland,” he wrote, “that the producers all around her coasts, in schooner or on land, fishermen, sailors, small farmers or loggers are now dumb slaves of a truck system which deprives them of their economic freedom? They are afraid to speak out because to do so would mean suffering for their families, but a hot sense of injustice can be felt, and a good deal of ominous grumbling heard, among the men themselves.”

In 1934 Newfoundland relinquished its dominion status in favour of a British-appointed commission of government [see Frederick Charles Alderdice], and Jackson initially welcomed the change as an opportunity to achieve non-sectarian, honest, and efficient rule. Two years later he was deeply disappointed by the continued economic difficulties, the lack of a policy for reconstruction, and what he considered to be a lack of interest on the part of the commissioners. As he complained bitterly to the commissioner for finance, Everhard Noel Rye Trentham, neither educational changes nor economic diversification was showing any noticeable fruit. He wrote: “I am disillusioned, the only people benefitting are a couple of individuals in many of the outports, and a third of St Johns.” For Jackson the cure to Newfoundland’s ills lay “not in charity but in a growing sense of competence, and direction toward economic security.”

Jackson considered education to be of great significance in human evolution. He wrote prolifically on religious education and worked to establish opportunities for young people in Newfoundland’s outports through summer schools, adult education, reading circles, leadership training, and private tutoring. He personally prepared gifted individuals for entry into Memorial University College, whose president, John Lewis Paton*, shared his passions for the Social Gospel and educational advancement. Among those whom Jackson encouraged and guided were Herbert Lench Pottle, a future member of the Commission of Government and cabinet minister under Joseph Roberts Smallwood*, and the eminent fisheries scientist Wilfred Templeman.

Well in advance of his time, Jackson was a fierce critic of the denominational-school system, which he held responsible for a needless duplication of services and for the poor educational standards outside St John’s, notably in the natural sciences. “We have got to break through the sectarian system with its waste, overlapping, and its criminal neglect of the child in small communities,” he wrote to his protégé Pottle. “This is not an old saw, boy, it is a real problem standing like a sturdy wall in our path, and someone has to keep hitting and kicking until a gap is made and the youth of Nfld march on to self-activity and self-discipline.”

Jackson also encouraged the forming of cooperatives and self-help organizations for fishermen, and he promoted among his parishioners a broadly based subsistence pattern that incorporated horticulture and the keeping of livestock. To advance such diversification he wrote popular pamphlets and articles, such as “Our friend the pig,” in which he advocated hog raising, and he penned a recurring section on gardening and health in the Monthly Greeting. He was well aware of international developments concerning cooperatives and participated in the first annual convention sponsored by the West Coast Co-operative Council on the subject. As it was for his theological mentor Rauschenbusch, the “co-operative way” was for Jackson intimately bound up with the social principle of Christendom and its fraternal ideals. “There are many who fear the idea of Co-operation,” Jackson wrote. “The fact is that it is the most hopeful Christian idea arising out of the welter of economic greed and failure today. We can find, through Co-operative Societies, the way by which there can be a release of the motive power of the spirit of our people such as can rejuvenate and reconstruct our producers and our country.”

With many other Social Gospel theologians, Oliver Jackson shared a postmillennial vision of the Kingdom of God, in which human initiatives were needed to create a just order for God’s children on earth. In the January 1934 issue of the Monthly Greeting he encouraged his readers, with special reference to Rauschenbusch, “to shift our emphasis from the individual and his safety, to that of the Kingdom of God and the individual’s responsibility for extending it.” As Jackson put it, this change in attitude “includes repentance, guilt, conversion, and sanctification, but gives a social instead of an individual content, and puts into the personal experience a demand, a responsibility, which challenge manhood and womanhood.”

A peace activist, Jackson promoted through talks and articles the importance of international cooperation and the work of the League of Nations. He strongly opposed totalitarianism, and in the St John’s Daily News he once challenged a local apologist for Francisco Franco to acknowledge the atrocities committed by the Fascists in the first months of the Spanish Civil War. Jackson considered Franco’s rule inimical to Spanish self-determination and the creation of “a righteous social and economic order.”

In 1936, citing his “valuable services” to community and church, King Edward VIII made Jackson a member of the Order of the British Empire (civilian division). A year later he drowned along with a student minister, Wallace J. Harris, when their boat, Mizpah, capsized in rough waters while they were visiting the Petites and Grand Bruit mission on the southwest coast. His body was recovered and interred in the General Protestant Cemetery in St John’s. Hailed after his death as the “apostle of the outports,” Oliver Jackson was remembered in Newfoundland by three buildings: Jackson House at Western Bay and, on Bell Island, Jackson Memorial School and Jackson United Church, which still stands.

Oliver Jackson’s numerous articles and editorials can be found in the Methodist Monthly Greeting (St John’s) from 1919 to 1925, and in its successor journal, the Monthly Greeting (St John’s), from 1925 to 1937. He occasionally contributed to the St John’s Daily News and authored at least two other articles: “Nature study,” N.T.A. Journal (St John’s), 24 (1932), no.2: 8–9; and “Church life in Newfoundland,” United Church Record and Missionary Rev. (Toronto), 13 (1937), no.11: 8–9.

Jackson’s activities as minister and administrator from 1911 to 1937 are documented in Methodist Church (Canada), The Methodist year book: including minutes of the annual conferences of Canada and Newfoundland (Toronto), 1911–25, and UCC, Newfoundland conference (Toronto), 1926–37. His local pastoral activities, with the exception of those carried out at Bell Island and Portugal Cove, are recorded in the Methodist/United Church parish records available at RPA. The official correspondence and documents from Jackson’s activities as superintendent of missions were likely destroyed in the fire that consumed the United Church Mission Office and Community Centre in St John’s on 28 Jan. 1945. Contemporaneous tributes and coverage of his death and burial can be found in the Daily News and Evening Telegram, the two major St John’s newspapers, from 4 to 12 Nov. 1937. One of Jackson’s sons, Professor Francis Lindbergh Jackson of St John’s, kindly made available to the author the documentation about Jackson’s being received as a “Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (civil division)” in 1936.

Two substantive and biographically important collections of unpublished correspondence were consulted in preparation for this biography: Jackson’s correspondence with John Lewis Paton of Memorial University College, St John’s (Memorial Univ. of Nfld, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Arch. and Special Coll., Coll-470), and letters that Jackson wrote to his protégé, Herbert Lench Pottle (in private possession). Pottle remembers his mentor in “A tribute to late Rev. O. Jackson,” Daily News, 10 Nov. 1937; Newfoundland, dawn without light: politics, power & the people in the Smallwood era ([St John’s], 1979), 51–52; and From the nart shore: out of my childhood and beyond (St John’s, [1983?]), 114–18.

The literature on Jackson is scant. The fullest appreciation of his life and work is a 20-page biography from the pen of his student and successor as superintendent of missions and field secretary of Christian education, H. M. Dawe, titled Apostle of the outports: a resumé of the life and work of Rev. Oliver Jackson, b.d., o.b.e. (Toronto, [1939?]). Other tributes and sketches include K. J. Beaton, “He has gone forward to God: a tribute from the boards of home missions and of Christian education,” United Church Record and Missionary Rev., 13 (1937), no.12: 4, and “There is sorrow on the sea,” New Outlook (Toronto), 12 Nov. 1937: 1043; H. M. Davis, “A terrible tragedy,” United Church Record and Missionary Rev., 13, no.12: 18–19, and “The last entry in the superintendent’s log,” United Church Record and Missionary Rev., 14 (1938), no.1: 12–13; H. M. Dawe, “Oliver Jackson – friend of youth – goes forward,” United Church Record and Missionary Rev., 14, no.1: 19–20. See also the more recent works of D. G. Pitt: “Oliver Jackson: pioneer and apostle,” Touchstone (Winnipeg), 16 (1998), 2: 47–54; “Prominent figures from our recent past: Rev. Oliver Jackson,” Nfld Quarterly (St John’s), 86 (1990–91), no.1: 32–34; and the entries for “Jackson, Oliver” in DNLB (Cuff et al.) and Encyclopedia of Nfld (Smallwood et al.), 3: 90.

Hans J. Rollmann, “JACKSON, OLIVER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jackson_oliver_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jackson_oliver_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Hans J. Rollmann |

| Title of Article: | JACKSON, OLIVER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2018 |

| Year of revision: | 2018 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |