Source: Link

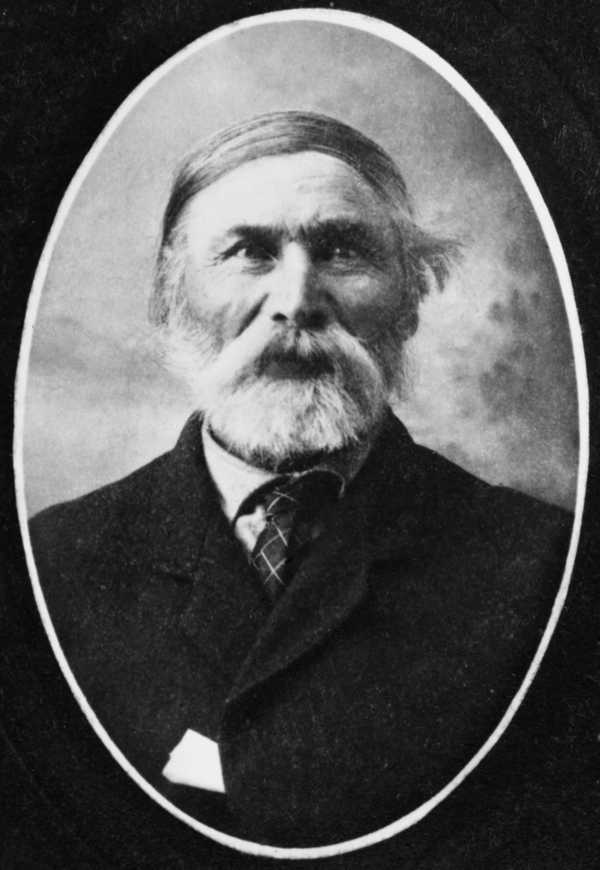

ISBISTER, JAMES, fur trader and farmer; b. 29 Nov. 1833, probably at Oxford House (Man.), third child of John Isbister and Frances Sinclair; m. 1 Jan. 1859 Margaret Bear at “Nepowewin Station” (Nipawin, Sask.), and they had at least 16 children, 9 of whom were still living in 1888; d. 16 Oct. 1915 in Prince Albert, Sask.

James Isbister was a leader of the people known in his day as English half-breeds or English natives; the designation Métis is now applied to them as well as to persons of French and Indian ancestry, and Isbister is recognized as a Métis. His father was an Orkneyman employed by the Hudson’s Bay Company and his mother an English Métis. He was well educated, probably having attended a school in the Red River settlement (Man.), and was fluent in English, Gaelic, Cree, Chipewyan, and Michif, the last a hybrid primarily of Cree and French. He followed his father into the service of the HBC, engaging as a labourer in August 1853. His entire career there was spent in the Cumberland and Saskatchewan districts, mostly in the region around Cumberland House (Sask.) and the forks of the North and South Saskatchewan rivers. Although his prospects of achieving a high position were limited by both systemic racism in the company and the low rank of his father, he rose rapidly from labourer to interpreter to postmaster and, finally in 1868, to clerk.

In 1862–64 and again in 1867–68 Isbister temporarily left the HBC; he would retire permanently in 1871. Company service was a means to an end for him. Through it he could afford to establish a farm on the lower North Saskatchewan River, on 3 June 1862. He and his wife, an English Métis, were the area’s first settlers and the site was initially known as the Isbister settlement. Four years later, the Presbyterian minister James Nisbet* erected a mission nearby and renamed the place Prince Albert. Isbister’s rightful claim to be the founding father of the community has largely been overlooked and credit given to the missionary instead.

Like many Métis, Isbister had a flexible economic strategy. To augment his agricultural income he carried freight for the HBC and worked at the government farm on the John Smith (Muskoday) Indian Reserve. He and his family lived on their property, river lot 62, until the early 1880s when, after acquiring another 160 acres nearby, lot 17, he sold it. Late in that decade his new farm had some 60 acres under crop, along with pasture for livestock.

After the troubles of 1869–70 at Red River [see Louis Riel*] any French and English Métis there lost their land. Dispossessed, they would flock to the forks of the Saskatchewan to re-establish their lives. Prince Albert became the largest English Métis settlement in the area; places such as Batoche and St Laurent (St-Laurent-Grandin) were French Métis centres. Soon the problem of land surveys became critical, not only for the Métis, but also for white settlers. The federal government was slow to respond to pleas for the surveys, without which no one’s title was certain. By the early 1880s the ownership of land had been made the central issue in the North-West Territories by ineffective or non-existent government action.

The struggle for secure title temporarily overcame ethnic differences and united virtually all the white and Métis residents of the territories. At the time, the English and French Métis were considered to be two distinct ethnic groups, and were often at odds with each other, largely because of religious differences which were encouraged by many white clergymen. Isbister, a member of the Church of England and a lifelong lay leader, set aside any sectarian feelings he may have had and joined in working for the common good. He took a leading role in the Settlers’ Union, which was established at Prince Albert on 16 Oct. 1883 to press for redress of grievances concerning land. The union represented the white majority as well as both Métis communities and was initially endorsed by the Prince Albert Times and Saskatchewan Review, the voice of the white population. It began organizing local committees and drafting a petition.

By the spring of 1884 both Métis communities agreed with Gabriel Dumont*’s opinion that they needed stronger advocacy than any current member of the union could provide. Louis Riel was their choice, and a delegation was sent to Montana to seek his aid. Its only English member, Isbister worked hand in hand with Riel upon his return to Canada, trying to achieve the union’s goals through “constitutional agitation,” as he later put it. However, mistrust and fear of Riel caused most of the white community quickly to withdraw from the once-common movement.

When the government’s insensitivity finally led to violence in March 1885 [see Lief Newry Fitzroy Crozier*], Isbister and most of the English Métis did not follow the new path taken by Riel. None the less, Isbister was imprisoned for five weeks at Prince Albert until the resistance was crushed. Upon his release late in May, he publicly defended his previous actions and criticized the recent widespread violation of civil rights. For his efforts he was condemned by the Prince Albert Times as a “coward” and a “liar.”

After 1885 Isbister fades into obscurity except for his parish activities. Briefly in the 1880s, however, he had been the most important leader of the English Métis and a driving force in uniting them and the French Métis, perhaps in the process sowing the seeds of the single Métis Nation of today.

GA, M7144, file 670000. NA, RG 15, 921, claim 323; 1328, esp. 22 July 1885. PAM, MG 3, D1; D2; HBCA, B.239/k/3; James and John Isbister search files. Saskatchewan Arch. Board (Saskatoon), Homestead files, 61409, 73871, 503265. Daily Sun (Winnipeg), 19 June 1885. Prince Albert Times and Saskatchewan Review (Prince Albert, [Sask.]), 1882–85. J. S. H. Brown, Strangers in blood: fur trade company families in Indian country (Vancouver and London, 1980). Can., Dept. of the Interior, Annual report (Ottawa), 1878–79, reports of the deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs, continued by Dept. of Indian Affairs, Annual report, 1880–85; Royal commission on rebellion losses, Report to the honourable the minister of the interior ([Ottawa, 1887]). Robert Choquette, The Oblate assault on Canada’s northwest (Ottawa, 1995). P. R. Mailhot and D. N. Sprague, “Persistent settlers: the dispersal and resettlement of the Red River Métis, 1870–1885,” Canadian Ethnic Studies (Calgary), 17 (1985), no.2: 1–30. Frits Pannekoek, A snug little flock: the social origins of the Riel resistance of 1869–70 (Winnipeg, 1991). D. P. Payment, “The free people – Otipemisiwak”: Batoche, Saskatchewan, 1870–1930 (Environment Canada, National Historic Sites, Parks Service, Studies in Archaeology, Architecture and Hist., Ottawa, 1990). Louis Riel, The collected writings of Louis Riel, ed. G. F. G. Stanley (5v., Edmonton, 1985), 3. Owen and Margaret Sanderson, Some places where the creaking carts ended (Prince Albert, [1980]). D. N. Sprague, Canada and the Métis, 1869–1885 (Waterloo, Ont., 1988). G. F. G. Stanley, The birth of western Canada: a history of the Riel rebellions ([2nd ed.], Toronto, 1960). The voice of the people: reminiscences of the Prince Albert settlement’s early citizens, 1866–1896, ed. Marion Lamontagne et al. (Prince Albert, 1985).

David Smyth, “ISBISTER, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isbister_james_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isbister_james_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Smyth |

| Title of Article: | ISBISTER, JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |