Source: Link

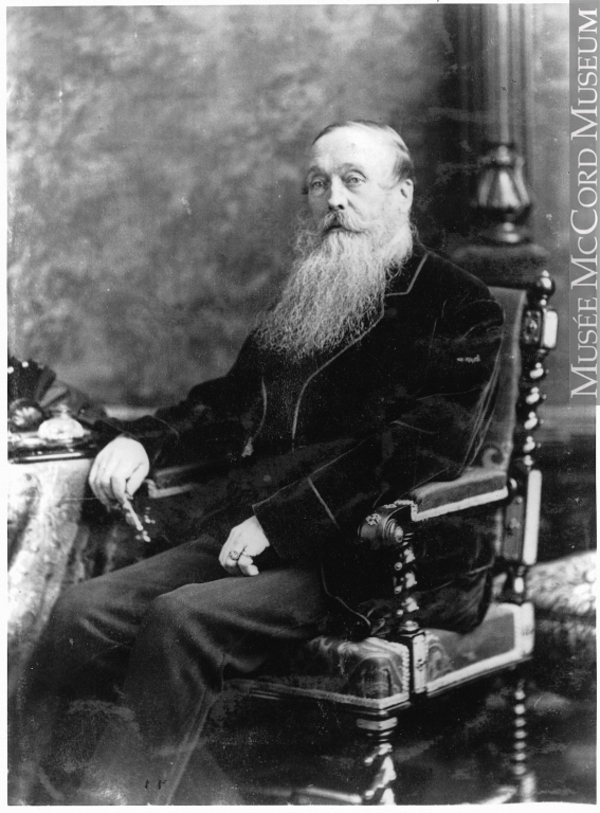

HOWARD, HENRY, doctor; b. 1 Dec. 1815 at Nenagh (Republic of Ireland); d. 12 Oct. 1887 in Montreal, Que.

After studying in Dublin and at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, Henry Howard immigrated to Kingston, Canada West, in 1842. He remained there until 1845 when he moved to Montreal, where he obtained a post at the Montreal Eye and Ear Institution and soon became a specialist in ophthalmology. Displaying considerable interest in scientific questions, from 1845 to 1851 he regularly sent articles to English medical journals and to the British American Journal of Medical and Physical Science (after May 1850 the British American Medical and Physical Journal) which was published in Montreal. In 1850 his reputation as a first-rate eye specialist spread throughout North America as a result of the publication in Montreal and London of his book The anatomy, physiology and pathology of the eye.

As a doctor Howard was involved in a wide variety of concerns in his field: he took an active role in organizations which from 1840 had concentrated on the interests of the medical profession and the advancement of medicine in Canada. From 1844 he belonged to the Montreal Medico-Chirurgical Society, founded the previous year to promote contact among and exchanges between the members of the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery, and by the time of his death he had numerous friends within this society, of which he was the senior person. In 1851 the St Lawrence School of Medicine opened; Howard lectured there in ophthalmology and otology, but his role was a minor one because of the school’s brief existence.

In the next phase of his career Howard made a further contribution to the development of medicine in Canada East. In June 1861 the governor general appointed him medical superintendent of the new insane asylum at Saint-Jean, the establishment of which represented a unique experiment in Canada East. The government had been unable to commit itself to financing construction of the Beauport asylum (the Centre Hospitalier Robert-Giffard) when it was founded in 1845 [see James Douglas] and had adopted a leasing system with management turned over by contract to private individuals who eventually became the owners of the buildings. In contrast, Saint-Jean was wholly financed by the government.

In 1872 Laurent-David Lafontaine, a physician who was a member of the Legislative Assembly of Quebec, questioned certain expenses incurred by the asylum, especially for the purchase of spirits, and recommended that the care of the insane be entrusted to a religious community. Howard defended his administration, and indignantly protested against the government’s desire to put all the psychiatric institutions of Quebec in the hands of private owners, whether professed religious or members of the laity. In his opinion the supervision of the asylums must of necessity be a matter for the medical profession in order to avoid any exploitation of the mentally deranged. In this regard Howard asserted that a system of state asylums offered better protection for the insane; using statistics, he demonstrated a higher percentage of cures at Saint-Jean than at Beauport, where the proportion of incurable patients had become alarmingly high as a result of the economy measures applied to the treatment of mental illness. Aware that the government was prepared to abandon its state asylum system to realize substantial savings, both in capital and operating costs, Howard proposed a compromise formula. While pursuing the objective of putting medical interests before financial ones in the care of the insane, he undertook to meet the cost of building an asylum on condition that the government would grant him a leasing contract similar to the one in effect at the Beauport asylum, which included provision for an annual government allowance of $143 per patient up to 650 patients, and $132 for each additional patient. Despite his plea the government decided in 1875 to transfer the patients of Saint-Jean to Longue-Pointe Lunatic Asylum (Hôpital Louis-H. LaFontaine, Montreal), opened in 1873 and run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence (Sisters of Providence).

Howard himself worked at the Longue-Pointe asylum from 1875 to 1887. During these years he represented the government as either a visiting physician or a member of the medical board which was set up in 1885. The government’s measures in the 1880s to regain medical control of the mental institutions, which had thus far been in the hands of the owners, probably gave him considerable satisfaction. Indeed, in 1885 the government of John Jones Ross*, following criticisms about the leasing system and the state of the asylums in Quebec as well as accusations of failure to institute reforms levelled by the opposition, decided to enact a law giving the government medical control of insane asylums. There were, however, violent confrontations between the members of the medical board and certain owners of asylums who opposed the “secularizing” measures of the government.

The administrative wrangles in which Howard was involved did not adversely affect his work as an alienist. His invention of a ventilation system is evidence of both the precarious state of Canadian asylums during the 19th century and the importance that he attributed to physical treatment in the cure of insanity. Howard defined insanity as “a physical disease caused by a pathological change in the sensory nerves and the organ of consciousness . . . .” Using the resources of logic and rhetoric, he expressed the conviction that any effective treatment would have to come from the application of natural laws, otherwise only the symptoms were being tackled. Moral derangement constituted the second essential element of Howard’s theory about mental illness. The natural order was to a morally sound society what the body was to an intellectually mature mind. In his opinion the ideal remedy would be for the intellectual and moral élite to contrive to isolate the insane in order to control the evolution of society, particularly by preventing such persons from reproducing.

Howard’s ability probably commanded respect. However, several of his colleagues, especially the French-speaking ones, criticized the dogmatic nature of his pronouncements and the implacable logic of his reasoning. In 1881, during a criminal trial, Howard corroborated the case for the defence which rested on the contention that the accused was not responsible by reason of insanity. According to the majority of the other specialists Howard’s arguments were not unassailable, and in their opinion the accused was of sound mind. The verdict of guilty shows the conservative attitude of the authorities in matters of insanity.

Howard’s participation in several Canadian and American medical associations, his political activities in the St Patrick’s Society, and his administrative and professional pursuits show he was an ambitious man with great intellectual energy. His most outstanding endeavour was the management of the Saint-Jean asylum. Thanks to his extensive experience as a mental specialist, he recommended administrative reforms of benefit in the treatment of the insane. On the other hand his theory about mental and moral derangement must be treated with some reservation, especially in view of its empirical nature.

[Henry Howard was the author of The anatomy, physiology and pathology of the eye (Montreal and London, 1850) and A rational materialistic definition of insanity and imbecility, with the medical jurisprudence of legal criminality, founded upon physiological, psychological and clinical observations (Montreal, 1882). He also published many articles for the British American Journal of Medical and Physical Science (Montreal) from 1845 to 1851 and the following articles for Canada Medical and Surgical Journal (Montreal): “Mental and moral science; with some remarks upon hysterical mania,” 6 (1877–78): 439–53; “Some remarks on the medical jurisprudence of insanity,” 6: 210–20; and “Responsibility and irresponsibility in crime and insanity . . . ,” 7 (1878–79): 347–58.

Information on conditions in asylums during the period may be found at ACAM which holds the correspondence between the archdiocesan authorities, the sisters of Longue-Pointe Lunatic Asylum, and the provincial government concerning the laws related to insane asylums, 1880–85; in the annual reports of the inspectors of prisons and asylums, reprinted in Can., Prov. of, Parl., Sessional papers, from 1860 to 1867, and in Qué., Parl., Doc. de la session, 1869 to 1888. r.s.]

Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer, 144–45. Fernand Harvey and Rodrigue Samuel, Matériel pour une sociologie des maladies mentales au Québec (Québec, 1974). Heagerty, Four centuries of medical hist. in Canada, II: 92–112, 119. H. E. MacDermot, One hundred years of medicine in Canada, 1867–1967 (Toronto and Montreal, 1967).

Rodrigue Samuel, “HOWARD, HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howard_henry_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howard_henry_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Rodrigue Samuel |

| Title of Article: | HOWARD, HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |