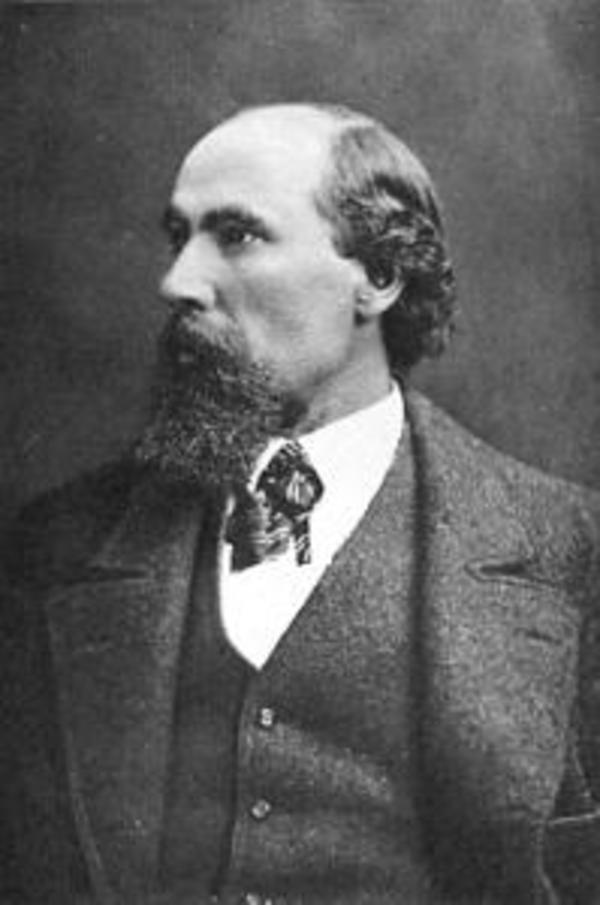

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HILL, JAMES JEROME, railway official and capitalist; b. 16 Sept. 1838 in Eramosa Township, Upper Canada, son of James Hill and Ann Dunbar; m. 19 Aug. 1867 Mary Theresa Mehegan in St Paul, Minn., and they had eight daughters, one of whom died in infancy, and two sons; d. there 29 May 1916.

James Hill’s grandparents emigrated from Armagh (Northern Ireland) in 1829, settling on a farm in Eramosa. His parents continued to work this land until 1848, when James Sr opened an inn in nearby Rockwood. Blinded in one eye in an accident at age 9, James attended the common school there and William Wetherald*’s academy. Perhaps to assert his identity, at 13 he appropriated the middle name Jerome, after the youngest brother of Napoleon, whose biography he had just read. His father’s death in 1852 cut short his formal education.

With his family pressed for money, Hill became a clerk in a grocery store in Rockwood and then in Guelph. Without a position from the fall of 1854, he left for New York in February 1856 and that summer accepted a clerkship with a commission and shipping firm in the booming city of St Paul, on the Mississippi. In 1865 he embarked on his own freight and forwarding business. The following year, in partnership, he built a warehouse, which was served by a siding of the St Paul and Pacific Railroad. An agreement in January 1867 gave him control of the line’s riverside facilities and in September he took Egbert S. Litchfield, who had connections to the railway, into the business, freeing himself to pursue new interests, including the trade in coal. Rather than take coal on consignment, as was the custom, he negotiated purchases and freight charges to achieve greater volumes and profits. By early 1876 he dominated the market and the next year he and other dealers merged into the Northwestern Fuel Company, with Hill as president.

Hill understood that the settlement of the Canadian west would increase commerce at St Paul, a key trade centre on the American route to Red River (Man.). Around 1867 Norman Wolfred Kittson* had transferred to Hill his business with free fur-traders in Rupert’s Land and begun to pass on orders for provisions from the Hudson’s Bay Company. Having bought out Litchfield in 1869, Hill entered into an agreement that year with fuel dealer Chauncey W. Griggs and in 1870 with steamboat captain Alexander Griggs. Two years later, with Kittson, they formed the Red River Transportation Company. Under Hill’s direction the company overcame the competition briefly offered in early 1875 by the firm of Fuller and Milne, and by 1877 the company was operating seven steamboats on the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Despite this success, Hill had already begun to act on his belief that boating had no future.

In 1869 Hill had met HBC officer Donald Alexander Smith, who was passing through St Paul to meet with Métis leader Louis Riel* on behalf of the Canadian government. The two businessmen shared concerns about the effect of the Red River uprising – in April 1870 Hill would report to the government on conditions at Red River and offer to carry supplies – and both recognized the need for better transportation. When Smith visited again, in 1873–74, he proposed to Hill and Kittson, who had been entertaining similar thoughts, that they acquire the St Paul and Pacific, then in receivership and incomplete in its extension to Manitoba. Without sufficient resources for this high-risk take-over, the St Paul partners relied on Smith, to whom they assigned their holdings in Red River Transportation, and George Stephen*, of the Bank of Montreal, to line up financing, primarily through J. S. Kennedy and Company of New York and Stephen’s bank.

By November 1878 the associates had finished the line to the border; in April 1879 the legalities of the acquisition were complete. On 23 May a new entity, the St Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad Company, began to operate the railway, with Stephen as president, Kittson as vice-president, and Hill as general manager. The Manitoba line came into being at a propitious time of economic recovery and settlement on the American plains, and, though running rights to St Boniface, Man., would not be granted to the company until May 1880, it rewarded its promoters handsomely. Hill would become president in 1882 and by November 1885 his interest would exceed $5 million in value. The line also provided the experience, connections, and capital necessary for the associates to undertake a far more ambitious scheme: completion of the transcontinental Canadian railway. Hill agreed to participate in the syndicate organized later in 1880 by Stephen, though he questioned the feasibility of the difficult section to be built north of Lake Superior. For Hill, the logical and more profitable route passed through St Paul to Chicago and Detroit or to Sault Ste Marie, Ont. In a gesture symbolic of his qualified commitment, he took out American citizenship on 18 Oct. 1880, three days before the syndicate signed a contract with the government of Sir John A. Macdonald*.

Hill’s sense of rail strategy told him that the Canadian Pacific Railway needed a western route close to the border to prevent potential competition. In 1881 he hired Albert Bowman Rogers* to find a southern way through the Rockies and, too busy to supervise construction himself, he recruited William Cornelius Van Horne of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St Paul as general manager. Nothing, however, reduced Hill’s apprehensions about the CPR. He complained about the way its construction materials tied up rolling stock on his Manitoba line, rejected its requests for lower rates for through passengers on this railway, and protested the rates it set to keep freight in Canada. In 1882 he objected when the Manitoba line, contrary to its charter but on Stephen’s instruction, purchased the Manitoba South-Western Colonization Railway in order to protect the CPR’s monopoly. In addition, he resented the fact that Smith and Stephen had reduced their Manitoba stock and that he had had to pledge his own shares to secure loans for the CPR. By early 1883 he could take no more: on 3 May he resigned from its board.

As successful as the Manitoba line was, it was still a regional carrier. In 1885–86, however, Hill allied it with the strategically important Chicago, Burlington and Quincy, which provided access to Chicago, eastern trunk lines, and new capital. Looking westward, he revoked an agreement not to invade the territory of the Northern Pacific. He pushed a line into Montana in 1887–88, extended the Manitoba road to Superior, Wis., where he opened a grain terminal and a line of modern lake steamers, and reduced rates on every front. Early in 1889 Hill boldly decided to carry on to the Pacific, a resolution that would propel him to the front rank of North American railway entrepreneurs.

Hill’s actions unsettled several of his eastern backers and provoked the Northern Pacific to contemplate a pre-emptive take-over, but Stephen and Smith came to his side and together the associates bought up whatever Manitoba stock they could. Stephen, who had grown discouraged with the CPR, promoted Hill’s Pacific project and, with Smith, joined the board of the company reorganized in 1889 as the Great Northern. It absorbed many existing lines, among them the St Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba, in 1890, and the new sections were constructed without federal subsidization. At every stage – routing, low-cost but careful building, generating traffic, and running – Hill, one of the few major executives of any railway who had personally mastered the details of operations, excelled. On 6 Jan. 1893, in which year he became president, the last spike was driven to tie Puget Sound, Wash., with St Paul and Duluth, Minn.

The Great Northern went into the depression of 1893 in sound condition, unlike the Northern Pacific. After their competitor fell into receivership, Hill and Stephen planned its buy-out. Though the Minnesota Circuit Court prevented this in 1895, the associates gradually purchased control and by 1901 had achieved de facto unification of the two companies. As well, in 1901 Hill acquired the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy. Antitrust laws did not permit an operational merger, but in late 1901, to consolidate ownership and block any take-over by railway giant Edward Henry Harriman, Hill created Northern Securities Company Limited to hold the securities of the three roads. The following year, however, President Theodore Roosevelt initiated an antitrust suit and in 1904 the Supreme Court ordered its dissolution. Its rail components were redistributed, and though Northern Securities continued as a holding company, the affair left Hill bewildered. “It really seems hard when we know that we have led all Western companies in opening the country and carrying at the lowest rates, that we should be compelled to fight for our lives against the political adventurers who have never done anything but pose and draw a salary.” In context the set-back was minor: by 1906 two-thirds of the trackage in the United States was in the hands of four groups, one being the alliance of Hill, John Pierpont Morgan, and the Vanderbilts.

The proximity of the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific to the border, and their branches to the north, made them factors in Canadian transportation. At the same time, the CPR’s ownership or lease of railways in the United States made it a competitor for American traffic. By 1888 Stephen and Smith had gained control of the Minneapolis, St Paul and Sault Ste Marie to keep it from the Grand Trunk and assumed that Hill would take it off their hands. He had no such intention, and complained bitterly. The CPR’s “Soo” line, completed in 1893 from Moose Jaw (Sask.) through Minneapolis to Sault Ste Marie, also concerned him. When Stephen joined the Great Northern, Hill had offered to purchase the “Soo,” but on terms he knew Van Horne would decline – a traffic-sharing arrangement. Still, from the mid 1890s the CPR was firmly established in Hill’s backyard, in North Dakota and Minnesota; he in turn challenged it in British Columbia and Manitoba.

Hill’s westward expansion had brought him into contact with Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt*, who in 1885–86 sought to connect his coalmines at Lethbridge (Alta) with the Northern Pacific. Though Hill doubted the business value of such a link – there were still fields to be mined in Montana – he worried about its nuisance value and was pleased with Stephen’s assurance that any charter would be killed by the CPR’s monopoly. Following the repeal of the monopoly in 1888 [see Thomas Greenway*], Galt built a line to Great Falls, in Montana Territory, where Hill and others were developing water-power and smelting operations. This time, aware that Galt held a charter to extend his railway to the valuable coalfields of the Crowsnest Pass area, Hill was interested, and in 1890 he gave Galt a contract for coal. In 1901 Galt’s son Elliott Torrance*, unable to finance the improvement of the Lethbridge-Montana railway, offered it to Hill, who agreed to take its American section on the condition that Galt widen the Canadian section.

By then opportunities in southeastern British Columbia, especially the Crowsnest and Kootenay regions, held even greater appeal for Hill. In 1891 he had rejected mla James Baker’s offer of coalfields in the Crowsnest and his charter for the British Columbia Southern Railway. Baker turned to the CPR and Hill proceeded to piece together his own line. The Kaslo and Slocan was built from Sandon to Kootenay Lake, where it met the steamers of his International Navigation and Trading Company Limited. The Bedlington and Nelson tied the lake to the border and connected, via the Kootenai Valley Railway, with the Great Northern in Idaho. In 1898 these pieces were merged into the Kootenay Railway and Navigation Company, controlled by an English syndicate but financed by Hill. At the same time, he tied up the other American entry to the Kootenays by purchasing the Spokane Falls and Northern Railway and its subsidiaries from the Northern Pacific [see Daniel Chase Corbin].

Although Hill was starting to be seen as a counterweight to the CPR in British Columbia, he hoped that the Great Northern, the Northern Pacific, and the CPR could withdraw from each other’s territory. An agreement between Hill and Van Horne in 1898 to fix rates and divide freight stood until 1901, when Hill, who probably never expected a permanent arrangement, launched a new incursion into southern British Columbia, with the intent of draining traffic to Great Northern lines in the United States [see John Hendry]. He perceived that mining operations and the potential for investment in the coalfields had matured to a point where a challenge to the CPR might be worthwhile. As well, he was developing an alliance with William Mackenzie* and Donald Mann* of the Canadian Northern. By purchasing the Vancouver, Victoria and Eastern Railway and Navigation Company from them and combining it with several smaller companies, Hill linked the coastal area to the Kootenay region via his American main line. Mann’s influence on his behalf with the provincial government paid off when Hill, over CPR opposition, received a charter for the Crow’s Nest Southern Railway. To secure traffic, notably coal and coke for the American market, he and his associates bought stock in the Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company Limited sufficient to give them control in 1906. Similarly, he invested substantially in mining companies and by 1905 had taken most of the ore and coal traffic away from the CPR.

The competition in Manitoba was more symbolic than real. In 1897 Hill had purchased the potentially troublesome Duluth and Winnipeg from the CPR, but more effective was public opposition to the CPR, particularly from 1900, during the successive governments of Hugh John Macdonald* and Rodmond Palen Roblin*. Hill shared the CPR’s concern over the province’s lease of the Northern Pacific and Manitoba Railway. In January 1901, arguing that their systems would suffer from provincially set rates, CPR president Thomas George Shaughnessy* urged Hill to purchase the Northern Pacific line since law barred the CPR from doing so. Hill declined. Though he thought that Mackenzie and Mann paid too dearly for the lease, he was probably pleased to see the CPR face new competition. But he did not leave Manitoba totally to the spreading interests of Mackenzie and Mann. After winning control of the Northern Pacific, in 1901 he formed the Manitoba Railway to combine its Manitoba subsidiaries; two years later he obtained charters for the Midland Railway Company of Manitoba and the Brandon, Saskatchewan and Hudson’s Bay Railway. In 1909 the Midland’s operating branches, which cut north and south across the “Soo,” were transferred to the newly formed Manitoba Great Northern.

The annual report of the Great Northern for 1916 valued its Canadian holdings at $37 million. This investment, as well as the interconnections between Hill’s Canadian and American railroads, had made him a wild card in the projection of a second Canadian transcontinental [see Charles Melville Hays] and a vocal supporter of reciprocity. From at least 1903, in a stream of speeches and interviews, he expounded “new trends of trade.” Publicly he emphasized geographical unity: “Canada is merely a portion of our own Western country cut off from us by the accidents of original occupation and subsequent diplomatic agreement.” If not part of the American economy, he told the president of the Illinois Manufacturers Association in 1905, Canada would become “our most formidable competitor.” Privately he recognized that the free admission of coal to the United States would enhance his Crowsnest investment. Hill lobbied hard – he even briefed President William Howard Taft – but in the end he was disappointed: reciprocity went down with the government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier in the election of 1911.

Biographer Albro Martin has concluded that Hill’s Canadian ventures, driven as they were by his “controlled aggression” toward the CPR, accounted for “millions of dollars in hopeless investments.” Even if less productive than his American operations – a likely but as yet unsubstantiated conclusion – the ventures do reveal the overlapping of transcontinental rail systems. The actual mileage of Hill’s railways in Canada was quite modest – just 600 miles by World War I – and its profitability may be indeterminable. Its greater importance was political and strategic, as an alternative route and potential competitor to the east-west transcontinentals. The possibility of a cheaper north-south route on the Canadian prairies had been mooted since the early proposals for the Pacific railway. More significant was the remarkable longevity, nearly 40 years, of the group informally known as George Stephen and Associates. Hill’s contribution was his imaginative ability to devise complexly integrated rail and water systems and, at the same time, personally command the minutiae of operations. Among North American executives, Hill, Van Horne, Harriman, and Collis Potter Huntington of the Southern Pacific/Chesapeake and Ohio were probably the best informed on operations.

A stickler for exact information on costs and efficiency, Hill gave his managers little freedom of action. His omnipresence rested upon the accounting system he imposed on his companies. As Gaspard Farrer, his English financier and head of Baring Brothers, explained of the railway operating sheet devised by Hill, “Once familiar with the principles it does not take ten to twenty minutes a month to grasp the contents. . . . The sheet is in fact an instantaneous photograph taken monthly of the work of every man who is spending money. . . . and where and how he spends it.” Hill was less attentive to keeping investors and his partners well informed. At times he clouded the real financial strength of his corporations, and his annual reports could be deliberate exercises in obfuscation – he did not want regulators to know how profitable his roads were lest they impose rate reductions. Rather than distribute more profits than were reasonable, he reinvested but concealed his actions in operating expenses and assured his partners that they would benefit through the appreciation of their holdings. Such financial wizardry worked hand in hand with Hill’s long involvement in corporate banking. A director of banks in New York and Chicago, he sat on the board of the First National of St Paul from 1880 to 1912, when he acquired control of the Second National and merged the two.

Hill’s management of his empire demanded intense application and on occasion left him physically and mentally drained. His was not a cheery outlook, for he anticipated difficulties which sometimes never materialized. “He does not enthuse,” Farrer observed in 1897. Hill did gradually reduce his involvement from about 1906; succeeded by his son Louis Warren in 1907 as president of the Great Northern, he served as chairman of its board for the next five years.

Away from work, Hill read avidly (Burns and Milton were among his favourites) and he looked forward each year to salmon fishing on the Rivière Saint-Jean west of the Îles de Mingan, Que., where he purchased exclusive rights in 1899. As well, he collected art with the same attention to detail that characterized his business dealings. He installed his 285 paintings, acquired from 1881 at a cost of $1.7 million, in what the New York Journal called in 1892 “a model art gallery of an American private palace.” Hill permitted visitors – college art classes, politicians and visiting dignitaries, businessmen, friends – to view his collection on obtaining tickets from his secretary.

As palatial as his St Paul mansion was, Hill felt most at home on his 3,000-acre farm, North Oaks, a short distance northwest of St Paul. There he diverted himself with crop and stockbreeding experiments, which gave him much to discuss in the public speeches he so greatly enjoyed giving. However busy he may have been, he was devoted to his family. Though not a member of any church, he accommodated himself to his wife’s Roman Catholicism and supported her in making theirs a strict Catholic household. Absorbed with so many concerns, he tended to ignore his health. In 1916 a neglected haemorrhoid became gangrenous. Doctors could not contain the infection, and Hill lapsed into a coma and died.

James Jerome Hill’s publications include “History of agriculture in Minnesota,” Minn. Hist. Soc., Coll. (St Paul), 8 (1898): 275–90; Development of the northwest; address delivered before the Chicago Commercial Association, October 6, 1906 ([Chicago?, 1906?]); The nation’s future: address delivered at the Minnesota State Fair, St. Paul, Minnesota, September 3, 1906 ([St Paul, 1906]); Address delivered before the Kansas City, Mo., Commercial Club, November 19, 1907 ([Kansas City, 1907]); Address at the dedication of Stephens Hall, Crookston, Minn., September 17, 1908 ([Crookston, 1908]); Address delivered at the Chicago convention of the Lakes-to-the-Gulf Deep Waterway Association . . . ([St Louis, Mo.?, 1908]); Address delivered at the Memorial Day exercises, Auditorium, St. Paul, May 30, 1908 ([St Paul, 1908]); Address delivered before the Farmers’ National Congress, Madison, Wisconsin, September 24, 1908 ([Madison, 1908]); The future of rail and water transportation . . . (New York, 1908); The natural wealth of the land and its conservation . . . ([Washington?, 1908]); Highways of progress (Toronto, 1910); Traffic growth and terminal needs . . . ([Minneapolis, Minn., 1910]); Brief history of the Great Northern Railway system ([St Paul?, 1912]); The country’s need of greater railway facilities and terminals . . . ([New York?, 1912]); Credit and railways after the war . . . ([St Louis?], 1914); and How to help business . . . (Chicago, 1915).

Hill’s papers are preserved in the James Jerome Hill Reference Library in St Paul.

Minn. Hist. Soc. Research Center (St Paul), Great Northern Railway Company papers; Northern Pacific Railway Company papers. “Art collection comes ‘home,’” Minn. Hist. News (St Paul), 32 (May/June 1991): 1. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). J. A. Eagle, The Canadian Pacific Railway and the development of western Canada, 1896–1914 (Kingston, Ont., 1989). Heather Gilbert, The life of Lord Mount Stephen . . . (2v., Aberdeen, Scot., 1965–77). Dolores Greenberg, “A study of capital alliances: the St. Paul & Pacific,” CHR, 57 (1976): 25–39. Julius Grodinsky, Transcontinental railway strategy, 1869–1893: a study of businessmen (Philadelphia, 1962). Homecoming: the art collection of James J. Hill, comp. J. H. Hancock et al. (St Paul, 1991). Albro Martin, James J. Hill and the opening of the northwest (New York, 1976; repr., intro. W. T. White, St Paul, 1991). A. A. den Otter, Civilizing the west: the Galts and the development of western Canada (Edmonton, 1982). J. G. Pyle, The life of James J. Hill (2v., Garden City, N.Y., 1917).

David G. Burley, “HILL, JAMES JEROME,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hill_james_jerome_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hill_james_jerome_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | David G. Burley |

| Title of Article: | HILL, JAMES JEROME |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |