Source: Link

HEUSTIS (Huestis), DANIEL D., Patriot filibuster and author; b. 1806 in Coventry, Vt, son of Simon Heustis; d. after 1846.

The son of a farmer “in moderate circumstances,” Daniel D. Heustis was one of ten children who were educated, he later recalled in his autobiographical Narrative, “as well as their limited means would allow.” The family was staunchly Presbyterian and republican; though he would claim at his trial in 1838 that he had “no religion,” as a youth he adopted his father’s republican views. “For the blessings of liberty and republican government,” he wrote, “I was early taught to cherish a lively gratitude. Tyranny and oppression, of every kind, I was led to abhor and detest.” At age 10 he moved with his family to Westmoreland, N.H., and in his early manhood he was employed by a farmer near Roxbury (Boston), Mass., and then by a storekeeper there. In 1834 Heustis settled in Watertown, N.Y., where he worked in an uncle’s “boating business” before joining a firm of morocco dressers as a sales and purchasing agent in 1835. Two years later he went into partnership with a cousin, butchering as well as trading in groceries and West Indian goods. At his trial the following year he described himself as a butcher; he was unmarried at the time and appears to have remained so.

It was during his commercial travels between 1835 and 1837 that he became familiar with the deep discontents that stirred many people in both Upper and Lower Canada. The outbreak of rebellion in the lower province in 1837 [see Wolfred Nelson*] induced him to “embark in the attempt to liberate the people of Canada from the thraldom of British tyranny.” It was not, however, until after William Lyon Mackenzie*’s defeat north of Toronto and escape to the United States that Heustis decided, at Watertown on 10 Jan. 1838, to give up business and devote himself entirely to “the cause of Canadian liberty.” He made for Rochester, where he encountered John Rolph*, Donald M’Leod*, and Silas Fletcher, all Upper Canadian fugitives, who sent him on with three cannon to Buffalo, the Patriot headquarters [see Thomas Jefferson Sutherland*]. There Heustis met Mackenzie and received a captain’s commission in the Patriot army. Returning to Watertown with Mackenzie, he was later arrested for violating American neutrality laws – part of the official American reaction to William Johnston*’s abortive Hickory Island raid – but was soon discharged.

That spring he was enrolled, along with 1,900 others, as a member of the Hunters’ Lodge at Watertown, then a hotbed of Patriot activity. Several weeks later he was one of the 50 men from Watertown who joined a larger force at Youngstown, N.Y., for the purpose of rescuing the Patriots captured after the Short Hills raid in June and jailed at Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake). The removal of the prisoners, including Jacob R. Beamer, Samuel Chandler*, and Linus Wilson Miller*, to Fort Henry at Kingston, however, caused the raiders to disband. Heustis next joined the force which left Sackets Harbor on 11 November to invade Upper Canada. Under the leadership of Nils von Schoultz, he participated two days later in the battle of Windmill Point, near Prescott on the St Lawrence River. Of the 186 men in the invading force, 177 were killed or taken prisoner [see Plomer Young*; James Philips].

Heustis, as one of the prisoners, was brought to Fort Henry to be tried before a court martial in December 1838. According to a dispatch later sent by Lieutenant Governor Sir George Arthur* to Lord Normanby at the Colonial Office, “persons of higher influence” entered a plea on Heustis’s behalf on the grounds that his “station in society (appeared) to have been rather above that of the generality of the brigands.” The plea, however, was rejected. He was found guilty of “piratical invasion” and on 17 December was sentenced to death. “We were in the hands of the Robespierres of Canada,” he dramatically recalled, “and the guillotine was in readiness to despatch its victims.” Heustis’s first appeal to Arthur for clemency, prepared in his cell late that month and conspicuously absent from his Narrative, was followed by petitions from residents and officials in the Watertown area, all affirming that Heustis had been misled in his Patriot actions. In April 1839, by which time ten of the Patriots involved in the Prescott action had been hanged, Heustis pleaded convincingly that he had been deceived by “evil and designing men in his Country and by Refugees and Rebels from this province to join in the late unwarrantable attack.” As a result of the appeals on his behalf, he was considered for a pardon by the Executive Council, though he was still regarded by one government official as “one of the most active & influential of the Brigands.” In the end, 60 of those not executed, including Heustis, had their sentences commuted to transportation for life to the British colony of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania).

While in jail in Fort Henry, the prisoners, almost all Americans, had been visited by Arthur, whom Heustis later described as a “short, stout-built man” with “a tyrannical look about him.” Soon after, wrote Heustis, the Americans celebrated the “ever glorious Fourth of July . . . as well as circumstances would permit. Out of several pocket handkerchiefs a flag was manufactured, as nearly resembling the ‘star-spangled banner’ as we could conveniently make it. . . . We had faced the enemy, as did the heroes of Bunker Hill, . . . and we saw no cause for self-reproach.”

In September 1839 the prisoners were taken to Quebec, where they were joined by 18 Patriots captured in western Upper Canada (including Elijah Crocker Woodman), 58 Lower Canadians, and 5 other criminals. All were put aboard the transport Buffalo, which sailed on 27 September and reached Hobart Town (Hobart) on 12 Feb. 1840. After some days in dock, where the prisoners were addressed by Lieutenant Governor Sir John Franklin, the Lower Canadians sailed on to Sydney and the Upper Canadians and Americans were taken to Sandy Bay road station, a few miles along the coast from Hobart Town. They were put to work on the roads. According to Heustis, the variety and quality of their food never changed: “one pound and five ounces of coarse bread, . . . three fourths of a pound of fresh meat, half a pound of potatoes, and half an ounce of salt, with two ounces of flour for skilly in the morning, and the same at night. This was the daily ration for each man, without variation, from one end of the year to another.” From a pint of the broth made from boiling the meat, “it was frequently no difficult matter to scrape off a spoonful of maggots.”

After four months at Sandy Bay road station the prisoners were divided up; some, including Heustis, were sent to Lovely Banks station, then to Green Ponds station, and later to Bridgewater (east of Hobart Town), where they worked on a causeway. From there Heustis and others went on to Jericho and Jerusalem, in the southern midlands of the island. “On their journey they passed through Jericho and crossed the River Jordan,” he commented sourly, “and at Jerusalem they ‘fell among thieves.’ There were no Samaritans in that region.” He was moved next to Browns River station, near the coast, where they found the “conveniences for flogging . . . in a high state of perfection,” though, he recorded, no American was ever flogged during his stay on the island.

On 16 Feb. 1842, after the normal two-year probation period had expired, Heustis and his fellow prisoners were granted tickets of leave, which allowed them to move freely within a designated area. Heustis was assigned to Campbell Town, in the midlands, where he earned good wages cradling wheat. The next year he had a visit from his brother. Heustis was recruited that year to hunt bush-rangers (escaped convicts), but did not have much success. He was none the less commended for his good “conduct” and, when free pardons began to be distributed in 1844, he was among the first to receive one, at Hobart Town. In January 1845 he joined 25 other former prisoners in signing on as replacements for an indifferent crew on the whaler Steiglitz, bound for New Zealand and northwestern America. The group left the ship and broke up at Honolulu, in the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands.

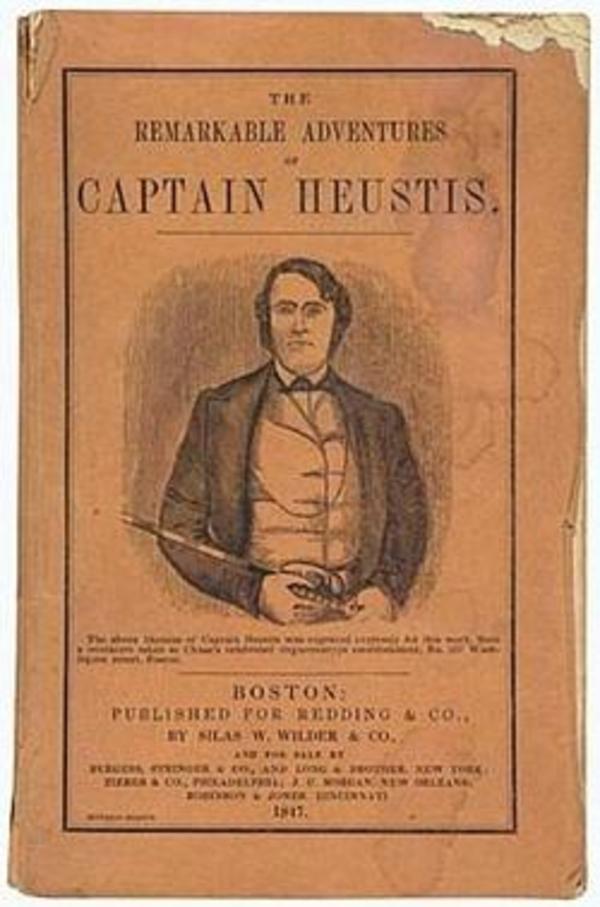

After various adventures and delays in California and Chile, Heustis eventually arrived in Boston on 25 June 1846 on the Edward Everett. He went on to Watertown to face a tumultuous reception from his family and friends, who “fired cannon and called out a band of music.” Shortly after, he paid a visit to the battlefield near Prescott; he noted later that he would “leave the reader to imagine the feelings with which I trod again that field of deadly strife.” In 1847 Heustis’s Narrative was published in Boston. Described by the historian Edwin Clarence Guillet* as “the most scholarly of the Patriot narratives,” it reveals the fine edge to which Heustis’s Patriot resentments had been honed during his years in penal servitude. He rejoiced that the régime of Sir George Arthur had passed. The emigrant, a recent publication of Arthur’s predecessor, Sir Francis Bond Head*, he dismissed as “the wail of a lickspittle of an aristocracy, who finds himself and his immediate friends kicked out of power . . . by the very men, to obtain whose countenance they shed patriot blood like water, and doomed scores of American citizens to the horrid life of penal colonists.” Above all, he bitterly lamented that “the Canadian people, in whose behalf we fought, were less true and faithful to the cause of liberty than our revolutionary sires.” At this point, in 1847, Heustis’s account ends, and with it such knowledge as we have of his life and adventures.

Daniel D. Heustis’s autobiography, A narrative of the adventures and sufferings of Captain Daniel D. Heustis and his companions, in Canada and Van Dieman’s Land, during a long captivity; with travels in California, and voyages at sea, was published in Boston in 1847.

Arch. Office of Tasmania (Hobart, Australia), CON 31/22; CON 60/1. PAC, RG 5, A1: 117005, 117011, 117049–51, 120741–55. Guillet, Lives and times of Patriots. M. G. Milne, “North American political prisoners: the rebellions of 1837–8 in Upper and Lower Canada, and the transportation of American, French-Canadian and Anglo-Canadian prisoners to Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales” (ba thesis, Univ. of Tasmania, Hobart, 1965).

George Rudé, “HEUSTIS (Huestis), DANIEL D.,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/heustis_daniel_d_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/heustis_daniel_d_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | George Rudé |

| Title of Article: | HEUSTIS (Huestis), DANIEL D. |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |