Source: Link

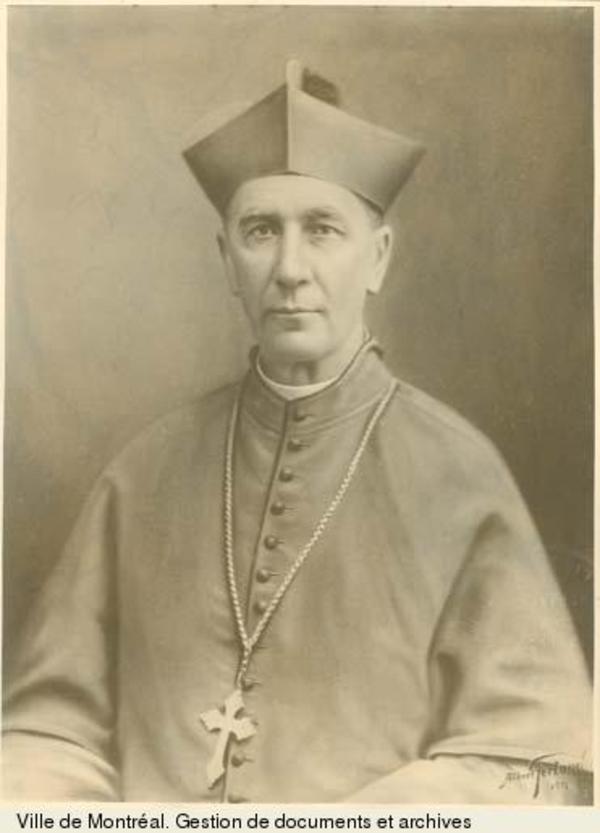

GRAVEL, ELPHÈGE (baptized Alphée), teacher, Roman Catholic priest, and bishop; b. 12 Oct. 1838 in Saint-Antoine-sur-Richelieu, Lower Canada, fifth of the 12 children of Nicolas Gravel, a farmer, and his second wife, Julie Boiteau; d. 28 Jan. 1904 in Nicolet, Que.

It was by an unorthodox and roundabout route that Elphège Gravel came to an ecclesiastical career. He began his classical studies in Lower Canada at the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe in 1849, continued them at the Jesuits’ Holy Cross College in Worcester, Mass., and completed them at the Petit Séminaire de Montréal. From 1859 he lived at the Grand Séminaire de Montréal, studying theology for thirty months; next he moved into the bishop’s palace for five months, during which time he was tonsured. In the fall of 1862 Gravel was at the Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir in Marieville, where he taught for two years. He then abandoned the ecclesiastical life and went to Quebec. In the summer of 1864 he attended the military school there and that fall he enrolled in law courses at the Université Laval. According to Abbé Isidore Desnoyers, “This year of set-backs and ordeals strengthened the young student in his original vocation.” Thus Gravel donned his ecclesiastical vestments once more and in August 1865 returned to the Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir. Still under the authority of the diocese of Montreal, he wanted to be on the strength of the diocese of Saint-Hyacinthe, where Bishop Charles La Rocque* had agreed to accept him provided that he teach at the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe. It was there that he received the three minor orders on 28 April 1869. On 2 April of the following year he was made a subdeacon and on 4 and 11 September, respectively, deacon and priest. Gravel, who by then was 31, informed his bishop that he wanted a different assignment. La Rocque refused his request, judging that the seminary needed him as a teacher. In 1871, however, he saw fit to appoint him curate in Sorel. Two years later Gravel received a similar appointment in Saint-Hyacinthe and in 1874 he became priest of Saint-Damien parish at Bedford in Stanbridge Township, located in the southernmost part of the diocese and near the American border.

In addition to Saint-Damien, Gravel served the missions of Saint-Ignace and Saint-Armand-Ouest, where he was assisted by a curate. As the second curé of this young parish, which had been created in 1866 for an area first colonized by loyalists, he was confronted with problems caused by the presence in 1878 of 1,700 Catholics, some of whom were Irish, and 1,500 Protestants. The question of schools and the issue of establishing municipal jurisdiction over parish lands were among the sources of tension. Further pastoral problems arose from other factors. Parishioners were dispersed over vast distances. There were differences of opinion about the boundaries of proposed parishes and quarrels over the location of places of worship. The proximity of the American border, which was easily crossed, caused troubles and made it difficult to exercise social and religious control.

Saint-Damien was also a poor parish, as its material circumstances in 1878 show. There was a temporary church of inadequate size which it was out of the question to replace and a fabrique having only the bare minimum for religious observances. The income for the curé was rather low: the tithe, the limited surplice fees, the collection (a concession granted by the bishop), and the bookkeeping for the fabrique brought Gravel only $350 to $450, depending on the year. In 1876 he considered himself unable to pay his mensal revenue to the bishop because of his modest income. According to him, the poverty of the parish had an effect on its religious life. Only a little more than a third of the families – 150 out of 350 – attended religious services regularly because the others “[did] not have a carriage.” It was true, he explained, that their absence was “an old habit which they developed when they lived far from the church [and which] has not yet been overcome. That will come in time,” he concluded. This circumstance, more readily than poverty, explains why every year some 200 Catholics did not make their Easter communion.

In the spring of 1878 Gravel was offered an appointment as curé of Saint-Nom-de-Marie in Marieville. He refused it, not because he would have felt uncomfortable to be near the Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir and the priests residing in it, but because he would have had to stay there. He could not do so because “out of filial piety” he had his mother and one of his sisters living with him. In the fall of 1880, however, he became the new curé of the cathedral parish of Saint-Hyacinthe. He was very close to the bishop, Louis-Zéphirin Moreau, with whom he had carried on a friendly correspondence; for his part, Moreau had often called on Gravel to conduct inquiries. The prelate was to have a better opportunity to form an opinion of this priest for whom, obviously, he had a strong kindred feeling. He was familiar with Gravel’s knowledge of the law, his talent as an orator, and his deep piety imbued with devotion to Rome. When in 1883 a candidate had to be chosen to head the proposed diocese of Nicolet (one who could be from neither Trois-Rivières nor Quebec, where the question of dividing the diocese of Trois-Rivières had aroused intense debates [see Calixte Marquis; Louis-François Laflèche*]), Bishop Moreau may have suggested Gravel.

Gravel was consecrated bishop of Nicolet on 2 Aug. 1885 and took the reins of authority on the 25th. The new diocese was of medium size, having 49 parishes and missions, all but one located in the counties of Nicolet, Yamaska, Arthabaska, and Drummond. With its population of some 80,000 Catholics, it was the third largest rural diocese in Quebec, after Saint-Hyacinthe and Rimouski. Twenty years later there would be 61 parishes, although no more than 88,000 Catholics. There were only about 1,500 Protestants, almost all in the southern townships, at the turn of the century.

When he arrived, Gravel had a diocesan clergy of 79, including parish priests, seminary teachers, and administrators. There was, however, no community of regular priests. In the report he prepared on the occasion of his ad limina visit in 1895, the bishop, who by then had 107 priests, declared himself satisfied with this number (there would be 119 by the beginning of 1905). In his evaluation of them, however, he expressed some reservations. He noted first that they managed property competently and were on close terms with their parishioners, who held them in high esteem. Moreover, he added, there was little in their personal lives that could give rise to scandal; when five cases of drunkenness and three of immorality had become known, he had put a stop to them and had even succeeded, he said, in rehabilitating the culprits. But Gravel then passed a harsh judgement on the intellectual calibre of his clergy, emphasizing their low level of education and in some cases their disturbing ignorance. In his view, these deficiencies might explain their lack of care in preparing their sermon material. (Ten years later his successor, Hermann Brunault, would note that the situation had improved and that the clerics were graduating from the seminary with a better education, an increasing number having done part of their theological studies in Quebec or Montreal, as Gravel had desired.) Finally, he accused them of lack of respect for the bishops, whom they criticized quite freely, but he noted that this shortcoming was common among the Quebec clergy.

Gravel made these remarks at a time when he was involved in a dispute with the priests of the Séminaire de Nicolet, who were entrenched behind the privileges of their long-established institution. It had trained most of the diocesan clergy and had resisted a planned closure when Bishop Laflèche of Trois-Rivières sought to strengthen the young seminary in his cathedral city; it had also led the struggle to get a new diocese created. Gravel accused its priests of undermining his authority over the clergy of the diocese. In short, the seminary wielded considerable influence and it is possible that he took umbrage at it. There is no doubt, however, that the quarrel, which even reached Rome, left its mark and intensified the conflict between him and some of his clergy, who had already been offended at the beginning of his episcopate by the appointment to administrative offices of priests from other dioceses, such as Louis-Victor Thibaudier, whom he had brought with him from Saint-Hyacinthe as his secretary.

The atmosphere was tense, therefore, when the question of designating a coadjutor arose. Opinions came from Trois-Rivères – Laflèche still had annexationist ambitions – and from the seminary, needless to say. The naming on 30 Sept. 1899 of Hermann Brunault, who taught at the seminary, seemed a victory for that institution, but Gravel was delighted. The appointment was timely, moreover, since he was in poor health and often had to leave the diocese to rest and recuperate. From 1899 he turned over to his coadjutor the task of visiting the parishes, thereby ending a custom begun in 1886.

During his episcopate Gravel had carried out six pastoral visitations. Devoting about 30 days a year to the task and stopping a day here and two days there, the bishop took three years to complete the rounds. Preceded sometimes by a secretary who examined the books of the fabrique, accompanied by at least two priests (occasionally oblates), and surrounded by the curés of neighbouring parishes, he fulfilled his dual role as pastor and administrator. On arriving in a parish, the bishop would peruse a report prepared by the priest. This document contained answers to some 80 questions, providing detailed information about the numbers of people in the parish, moral standards, participation in rites, and the management of church property. The bishop would pick out some of the data and incorporate the information into the minutes of the pastoral visit. These minutes demonstrate how much attention he paid to property management and finances and show the paramountcy of material and financial matters: his central concerns were the church building, the presbytery, and the fabrique. There were many instances when Gravel intervened in favour of repairing or constructing churches and presbyteries, or sometimes to discourage such a step, as happened during his visit in July 1895 to Saint-Cyrille. He agreed that the church was no longer large enough, but he gave two reasons for not authorizing the desired addition: the forthcoming creation of Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Conseil parish, which would draw away some of the congregation, and especially the expected closing of a lumber industry which would cause about 50 families to leave in search of work. Since he was more knowledgeable than the parishioners and aware of the sizeable population shifts in the diocese of Nicolet, Gravel gave an informed final opinion.

Financial matters left their mark on Gravel’s episcopate from the outset. There was no moderating of antagonism with the creation of the diocese, witness the altercations arising from the problem of sharing the accumulated assets and debts which faced Trois-Rivières and Nicolet. Rome announced its decision on 21 Jan. 1888: neither diocese owed anything to the other. Gravel at this time considered replacing the old and dilapidated fourth parish church with a cathedral church. Work on it did not begin until 1897, for lack of funds. Two years later, still unfinished, it collapsed, leaving nothing but ruins and debts. Even though the liability of the builders was proved, the bishop received little compensation. Another cause for concern was the income of the clergy, which the curés were insisting should be adjusted. They were able to show that recent changes in agriculture, as well as the consolidation of villages and increase in the number of wage-earners, had led to a situation where the tithe alone was no longer sufficient. Gravel had come to this realization and had taken measures as necessary. But he hesitated a long time before issuing a general edict. He began by approaching the curés, who came forward with solutions that suited them. He listened cautiously to all suggestions and waited until his decision was accepted by everyone. For many the general regulation of 1891, which laid upon all the faithful, both farmers and workers, the responsibility for maintaining the clergy, confirmed the status quo. The bishop’s hesitation and precautions nevertheless gave the impression that its application was not a foregone conclusion. But at least Gravel had been able to satisfy the majority and show the others that Nicolet was not taking a different approach from that of the diocese of Trois-Rivières, where Laflèche had adopted a similar measure that year. The similarity was no mere coincidence. Gravel was also responsible for the territory of the diocese and was called on to divide parishes in order to create new ones. Here, too, he met with the opposition not only of parishioners, but also of curés, who considered themselves wronged, being deprived of income. The correspondence occasionally reveals unkind and even acrimonious exchanges, which justify his opinion of the clergy. Where attempts to convince failed, authority prevailed. There is no doubt that the climate of relationships was affected.

First and foremost a shepherd of souls, Gravel typified the prelate assiduously spreading the Roman Catholic faith. He developed a pedagogy based on it. For example, because he wanted pastoral visitations to take on the character of a “true retreat,” special importance was given to preaching, confession, and communion. His activities were aimed essentially at giving concrete expression to what is called religious ultramontanism: Christ-centred and Marian worship, devotion to the saints, the worship of relics, and the practice of pilgrimages as a model of public prayer and a magnificent example of the display characteristic of Roman Catholic piety. His devotion to Bishop François de Laval* and to relics was exemplary. He encouraged Calixte Marquis, about whom he had no illusions, to build a chapel as a repository for the many relics he had collected, thanking him for his valuable donation of several of them to the episcopal church. Inheriting the fruits of the religious acculturation achieved by work several decades earlier, Gravel was able in 1895 to express his complete satisfaction that fewer than “25 persons fail to make their Easter obligation as a result of their faith weakening.”

In the diocese, ecclesiastical and clerical thought was disseminated largely through the teaching carried on by religious congregations of women, especially the Sisters of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, who directed no fewer than 15 convents [see Edwige Buisson]. The Brothers of the Sacred Heart, one of the two male congregations (the other being the Brothers of the Christian Schools), had their provincial house in Arthabaskaville (Arthabaska). During Gravel’s episcopate, educational institutions continued to increase in number. In 1886 he had some Sisters of Charity come from Saint-Hyacinthe to Nicolet, where they founded the Hôtel-Dieu [see Aurélie Crépeau]. Ten years later he brought in the Sisters Adorers of the Precious Blood, and in 1898 the Little Sisters of the Holy Family arrived at the seminary, where for a time they worked in the service of the bishopric.

In this way Nicolet received a bit of the prestige the bishop wanted to confer on it. Elphège Gravel indeed made great efforts to foster the development of the large rural village that was Nicolet, in order to make it into a cathedral town. His correspondence with federal cabinet ministers shows how much hope he placed in works connected with river and rail transport. In this respect he was a man of his day, knowledgeable in using the influence that went with his social and religious role. It would have been surprising therefore if he had not become involved in politics. His friendly relations with the Liberal bourgeoisie of Arthabaskaville were obvious, certainly too obvious for some, including Laflèche. He was also imprudent enough to become involved in the quarrels of Franco-Americans. Friendship led him to take sides and he was caught in a trap from which he extricated himself in great embarrassment. His thorough familiarity with the situation, however, is shown by a lucid opinion he expressed in 1895 about the future of the French language in the New England states; in it he distinguished language from religion and recognized that the process of Americanization was taking its toll.

Arch. de la Chancellerie de l’Évêché de Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué., Isidore Desnoyers, Hist. de la paroisse de Saint-Damien, 8 déc. 1885; Reg. des lettres des évêques. Arch. de l’Évêché de Nicolet, Qué., Corr. des diocèses, 1885–1904; Rapports paroissiaux; Reg. des insinuations ecclésiastiques, A, B; Reg. des lettres, 1–3. Arch. du Séminaire de Nicolet, F017 (Elphège Gravel). Arch. du Séminaire de Trois-Rivières, Qué., 0226 (fonds Elphège Gravel). Denis Fréchette, Le diocèse de Nicolet, 1885–1985 ([Nicolet, 1985]). Claude Lessard, Le séminaire de Nicolet, 1803–1969 (Trois-Rivières, 1980). Mandements, lettres pastorales et circulaires des évêques de Nicolet (12v. parus, Nicolet, 1904– ), 1. Yves Roby, Les Franco-Américains de la Nouvelle-Angleterre (1776–1930) (Sillery, Qué., 1990). Jean Roy, “Le clergé nicolétain, 1885–1904: aspects sociographiques,” RHAF, 35 (1981–82): 383–95; “L’invention du pèlerinage de la Tour des martyrs de Saint-Célestin (1898–1930),” RHAF, 43 (1989–90): 487–507; “Les revenus des cures du diocèse de Nicolet, 1885–1904,” CCHA Sessions d’étude, 52 (1985): 51–67. Philippe Sylvain et Nive Voisine, Les XVIIIe et XIXe siècles: réveil et consolidation (1840–1895), vol.[3] of Histoire du catholicisme québécois, sous la direction de Nive Voisine (4v. parus, Montréal, 1984– ). Nive Voisine, “La création du diocèse de Nicolet (1885),” Les Cahiers nicolétains (Nicolet), 5 (1983): 3–41; 6 (1984): 147–214.

Jean Roy, “GRAVEL, ELPHÈGE (baptized Alphée),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 1, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gravel_elphege_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gravel_elphege_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Roy |

| Title of Article: | GRAVEL, ELPHÈGE (baptized Alphée) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 1, 2024 |