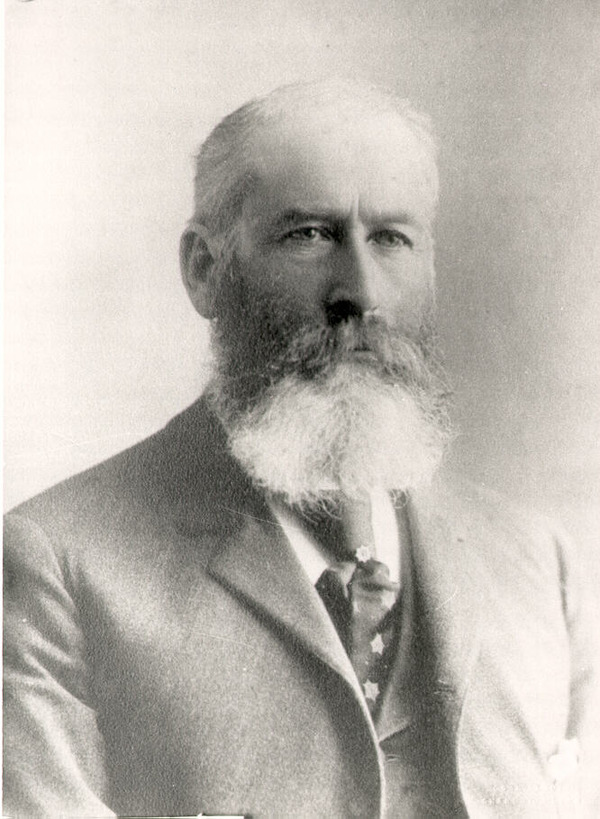

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FARQUHARSON, DONALD, teacher, businessman, publisher, and politician; b. 27 July 1834 in Mermaid, P.E.I., son of John Farquharson, a farmer, and Frances Stewart; m. first 15 March 1860 Dopson May Edwards Smith (d. 1868) of Pownal, P.E.I., and they had two daughters and two sons; m. secondly 20 Oct. 1870 Sarah Moore of Charlottetown, and they had two daughters and a son; d. there 26 June 1903.

Educated at the local school, Donald Farquharson later attended the Central Academy in Charlottetown. He taught school for a time before opening a store in 1860 on the West River, at MacEwen’s Wharf (near New Dominion). Farquharson and his partner, Theophilus Stewart, built up the business, which in 1887 included wholesale, milling, and shipping operations. By that time, in partnership with a son, Farquharson had started a general mercantile company in Charlottetown and had taken up residence there. He was a founding member, part owner, and later president of the Patriot Publishing Company, and a director and major shareholder of the Merchants Bank of Prince Edward Island. He also ran a starch factory at Long Creek and a lobster-canning factory at Canoe Cove. In addition, he owned, by deed or mortgage, numerous residences and considerable land. At his death he was reputed to have been one of the wealthiest men in Charlottetown.

In public life Farquharson was for many years a member of the city’s school board. A Liberal, he was first elected to the provincial legislature in 1876 for Queens County, 2nd District, as a “Free Schooler” and supporter of the Protestant coalition led by Louis Henry Davies*. He would be re-elected in every election until 1901, when he resigned to contest a federal by-election. He was a minister without portfolio in 1878–79 in the dying days of the Davies coalition, and in 1891–97 in the government of Frederick Peters. He was not named to the cabinet of Alexander Bannerman Warburton*, who succeeded Peters in 1897, but when Warburton retired to the bench the following year, Farquharson was chosen to succeed him as premier.

Possessed of a nervous temperament that struck all who knew him, Farquharson achieved success in public life through sheer determination and energy. A highly partisan and combative politician, he held strong, complex, and, in some instances, contradictory views. He had no sympathy for the position of the supporters of denominational schools, as evidenced by his election campaign of 1876 and by his attempt in 1888 to have exempted from taxation only schools that were subject to government inspection. Yet he voted with the Conservative opposition against the Land Assessment Act of 1877, which was introduced by the coalition government to support the new Public Schools Act, because he believed it would be unfair to Queens County. An ardent supporter of free trade with the United States, he regularly moved or supported free trade resolutions in the legislature, and in 1885 he said that the Island should move for separation from the dominion if justice was not done on tariff matters.

Farquharson became a persistent critic of the “extravagance” of the administration (1879–89) of William Wilfred Sullivan*, called regularly for retrenchment in public expenditures, and moved for the reduction of members’ pay. In 1879, however, he opposed his own government’s bill to do away with the province’s upper house because “if that branch of the Legislature were abolished, people might come here by the thousands, out vote property holders of this country, and leave them perfectly helpless.” He held this view for many years. The bill of 1893 which finally created a single-chamber legislature provided that half of its 30 members be elected only by property owners. Because of this provision, Farquharson believed that owners’ rights were adequately protected, and he supported abolition of the Legislative Council.

A teetotaller, Farquharson was a confirmed prohibitionist. In 1887, with a plebiscite pending in Charlottetown under federal temperance legislation, Premier Sullivan had introduced a local-licence act. All except Farquharson agreed that some regulatory act was necessary. He preferred to license no one and enforce total prohibition. Ironically it was his management of the issue when he was premier that gave rise to some of the harshest criticism of him. His pragmatic attempt to strengthen provincial licensing legislation in 1899 was condemned equally by the advocates of prohibition and by the advocates of licensing. The prohibitionists, led by the Morning Guardian, were furious that Farquharson, the “prohibitionist Premier,” had “sold out” to the liquor interests by permitting licences at all. And the supporters of licences were angry because the bill was too restrictive. Even some members of his own party, including Arthur Peters, were opposed, particularly because the bill prohibited selling in private clubs. After conferences with both sides, a less restrictive act was passed. Deeply hurt by the controversy, Farquharson came back with a prohibition bill the following year. Despite protests from some of Charlottetown’s “leading citizens,” the bill received royal assent. Farquharson made no changes to this act in 1901, and his resignation that year spared him further abuse over the controversial issue.

Farquharson experienced less difficulty in federal-provincial negotiations. Sullivan had blamed all of the Island’s financial and economic problems on Ottawa’s failure to provide an efficient ferry service to connect it with mainland railways. Frederick Peters and Warburton continued this line of argument, with only modest success, but Farquharson tried a somewhat different approach. In a memorial to Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* in March 1901 asking for increased federal subsidization, he based the Island’s case on fiscal need, emphasizing the province’s lack of mines, forests, and other sources of revenue and “the unfavourable terms upon which we entered the Union.” Unfortunately the effect of the appeal was lost because the following month Farquharson’s government was awarded $30,000 annually as compensation for the lack of winter communication. It was one of his last successes as premier, for he resigned in October to contest the by-election for the federal constituency of Queens West.

Possibly Farquharson’s only disappointment as a politician followed from his election in January 1902 to the House of Commons. As minister of marine and fisheries, Louis Henry Davies had been the Island’s representative in the federal cabinet since Laurier’s election in 1896. In 1901 he was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada. The plan of the Island’s Liberals was for Farquharson to resign and contest Davies’s seat. They thought that traditional Maritime interest in the marine and fisheries portfolio, combined with Laurier’s past recognition of the “principle” of replacing retired ministers with former premiers, would force the prime minister to appoint Farquharson to the cabinet vacancy. As expected, Farquharson won the seat in 1902, but Laurier, who seems not to have been consulted and who, in any case, wanted to add members from the northwest, refused to name him to the cabinet. Reputedly Farquharson’s great disappointment over this rejection contributed to his death the following year. Some compensation may have been in the offing: at the time of his death the Daily Patriot reported that his name had been “freely mentioned” as the Island’s next lieutenant governor.

A farmer’s son from Mermaid, Donald Farquharson had made an outstanding career for himself. Most would have agreed with the Daily Patriot’s summation: “Born into circumstances which were not golden from the world’s standpoint, he early set his face against adversities; his strength of character, indomitable perseverance, and sturdy will, overcame all obstacles and his reward was a pinnacle of success which is reached by few.” He was buried from Zion Presbyterian Church in Charlottetown, of which he had been a faithful member, and was interred in the Peoples Cemetery there.

NA, MG 26, G; RG 31, C1, 1841, 1861, 1881, 1891, Prince Edward Island. PARO, Acc. 2741/2–14; RG 25, ser.19; Supreme Court of Prince Edward Island, Estates Div. records, liber 16: f.197 (mfm.). Peoples Cemetery (Charlottetown), Tombstone inscription. P.E.I. Museum, Geneal. Div., Licence book no.6: 146; Marriage book no.7 (1856–63): 445; no.11 (1867–71): 459. Examiner (Charlottetown), 1868–80, continued as the Daily Examiner, 1881–1903, 26 June 1903. Morning Guardian, 1890–1903. Patriot (Charlottetown), 1868–81, continued as the Daily Patriot, 1881–1903, 25–26 June 1903. Canada’s smallest province: a history of P.E.I., ed. F. W. P. Bolger ([Charlottetown], 1973), 232–88. Canadian directory of parl. (Johnson). Directory, Charlottetown, 1887. R. M. Farquharson, Family Farquharson (n.p., 1987). Illustrated historical atlas of the province of Prince Edward Island . . . ([Toronto], 1880; repr. Belleville, Ont., 1972). W. E. MacKinnon, The life of the party: a history of the Liberal party in Prince Edward Island (Summerside, P.E.I., 1973). A. E. Mellish, “Canadian celebrities, xxv: Hon. Donald Farquharson, premier of Prince Edward Island,” Canadian Magazine, 17 (May–October 1901): 220–22. Mercantile agency reference book, September 1876. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Debates and proc., 1876–93; Journal, 1876–93; Legislative Assembly, Journal, 1894–1903; Legislative Council, Journal, 1876–93.

Frederick L. Driscoll, “FARQUHARSON, DONALD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/farquharson_donald_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/farquharson_donald_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Frederick L. Driscoll |

| Title of Article: | FARQUHARSON, DONALD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |