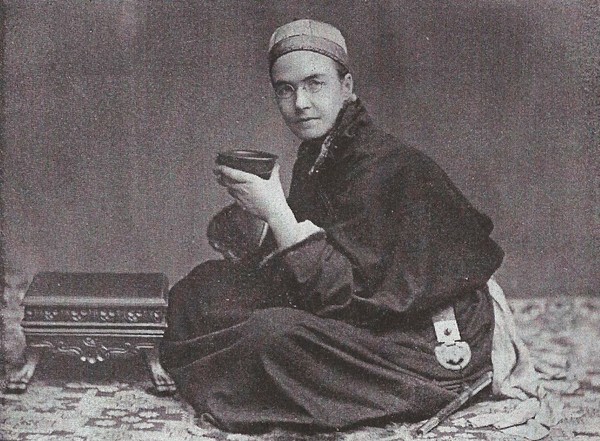

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

CARSON, SUSANNA (Rijnhart; Moyes), physician, medical missionary, and author; b. c. 1868 in Chatham, Ont., daughter of Joseph Standish Carson and Martha —; m. first 15 Sept. 1894 Petrus Rijnhart in Newbury, Ont., and they had a son; m. secondly October 1905 James Moyes, and they had a child; d. 7 Feb. 1908 in Chatham.

Active as a child in the Methodist churches of Chatham and Strathroy, Susanna Carson (usually called Susie) was inspired to become a foreign missionary. Her father, a public-school principal and later an inspector of schools, was a progressive educator who demanded academic excellence from all his children. In 1879 he responded to an advertisement placed in the Toronto Globe by Elizabeth Smith* for “Ladies wishing to study medicine in Canada.” He was “heartily in sympathy” with the medical program for women that she proposed to establish in Kingston, but his interest was hypothetical since his daughters had not finished school. Susie did enter Woman’s Medical College in Toronto [see Emily Howard Jennings] five years later, and she graduated in its second class with an md, cm from Trinity College in 1888. She practised in London, Ont., with her sister Jennie S., also a graduate of Woman’s Medical. Following their father’s death in 1889, they returned home to Strathroy, where they continued in practice.

In 1894 Susie married Petrus Rijnhart, a Dutch enthusiast who had come to Toronto in 1889 and learned English while working in a factory. He had sailed in 1890 for China, where he joined the nondenominational, British-based China Inland Mission and had been stationed in Lanzhou, the last city before Central Asia. The small missionary community there was noted for its frontier spirit. Rijnhart was dismissed by the CIM in 1893, apparently because enquiries in Holland had revealed him to be an imposter. Returning to Toronto at a time when most Christian denominations were clamouring for missionary representatives in so-called heathen countries, he found a ready audience for his charismatic appeal for missions to Tibet (Xizang province, People’s Republic of China).

Whether Susie knew about Petrus’s past is not known. A few weeks after their marriage, the Rijnharts set out for Tibet as independent missionaries supported by the Cecil Street congregation of the Disciples of Christ in Toronto. Criticized by missionary societies as impractical if not reckless for working outside established missionary networks, Susie wrote that she felt “specially called to do pioneer work” and believed firmly in apostolic initiative: “Christ does not tell his disciples to wait, but to go.” The 2,000-mile journey across China by houseboat and mule-cart took six months. They settled beyond Lanzhou at Lusar, a dusty one-street town located inside the border of Outer Tibet (Qinghai province) and near one of the largest Buddhist monasteries in Central Asia. The Rijnharts became “firm friends” with the head abbot, Mina Fuyeh. During their first year, 1895, they were isolated by a Muslim rebellion, which left 100,000 dead and dozens of villages destroyed. Once hostilities ceased, they treated the Muslim wounded, just as they did the Buddhist. Their medical work opened doors, but their evangelistic efforts had no visible effect. In their three years together in Tibet they would record no converts.

The Rijnharts’ next station was Tankar, a trading town where they were rarely visited by foreigners except for fellow missionaries. They could have remained on the fringes of the “Sealed Land,” but their goal was always its holy capital, Lhasa, which few foreigners had entered. “If ever the gospel were proclaimed in Lhasa,” Susie wrote, “some one would have to be the first to undertake the journey, to meet the difficulties, to preach the first sermon and perhaps never return to tell the tale – who knew?” On 20 May 1898 the Rijnharts set out for Lhasa with their ten-month-old son, three guides, many horses, enough food for a year, and 500 New Testaments.

The trip was a nightmare from beginning to end. The Rijnharts’ baby died, they were attacked by robbers, and their guides deserted. On 26 September Petrus spied an encampment of nomads across a river and went to seek their help. Susie never saw him again. For three days she waited, her revolver in her lap, “alone with God.” Two months later, after falling in with some “truly wicked men,” she reached other missionaries in Tachienlu (Kangding), in Sichuan province. When a consular investigation revealed nothing about the disappearance of her husband, she returned to Chatham in 1900, her health broken and her hair turned white by her ordeal.

On a lecture tour of Canadian churches, Dr Rijnhart was described as “a Canadian heroine” with a “most thrilling story of missionary exploration, sacrifice, and possible martyrdom.” She was persuaded to write With the Tibetans in tent and temple, a testament, she stated, to her husband’s “burning ambition to be of service in evangelizing Tibet – whether by his life or his death, he said, did not matter.” The book’s second purpose was to use her long acquaintance with Tibetan culture to correct accounts written by other travellers after brief sojourns.

Susie Rijnhart returned to Tachienlu with several associates in 1902 to found the Disciples of Christ mission to Tibet, which would eventually count seven converts. In 1905 she married James Moyes, the first missionary to greet her after her tragic trip in 1898. Like Petrus Rijnhart, he had limited education, having been a shop assistant and a coalminer in Scotland before joining the CIM. He had to resign in order to marry Susie, because of her past connection to Rijnhart. When her health failed, they moved to Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan, to work with the Christian Literature Society. In 1907 they returned to Canada and settled in Chatham, where Susie died in the local hospital, attended by her sister Jennie. Her final illness may have been complicated by childbirth, for she left a two-month-old baby. Within a week Moyes applied to the CIM, which refused to reaccept him, and to the Canadian Methodist mission in Sichuan, which felt he was not “a man of the calibre . . . desired in our missionaries for West China.”

Susie Carson Rijnhart Moyes was a gentle physician whose life epitomized the dangers of pioneer missionary work: much sacrifice but few results. The Disciples mission folded after her departure and she left no lasting imprint on Tibet. Her monument is her book, which found a readership among many missionary societies. A moving story of Christian adventure tinged with a sense of cultural superiority, it is largely free from the bombast of so many missionary records. Though utterly convinced of the supremacy of the gospel, she maintained that missionaries should not “assume an air of ridicule and contempt for the religious ideas and practices of peoples less enlightened.” It can be read today as a moving, sympathetic witness of Tibet before its destruction in the 20th century.

Susie Carson Rijnhart’s account of her adventures, With the Tibetans in tent and temple; narrative of four years’ residence on the Tibetan border, and of a journey into the far interior, was published at Chicago in 1901, and has been reprinted (New York, 1911).

There is an obituary of her in the Canada Lancet, 41 (1907–8): 566, but it is inaccurate. A better summary appears in the Age (Strathroy, Ont.), 13 Feb. 1908.

Billy Graham Center Arch., Wheaton College (Wheaton, III.), Coll. 215 (China Inland Mission/Overseas Missionary Fellowship records), China Council minutes, files 2-36-37 (mfm. at the Overseas Missionary Fellowship Arch., Toronto). NA, RG 31, C1, 1891, Strathroy, Ward 1: 28 (mfm. at AO). UCC-C, 14/3/1, file 72; Biog. file. Univ. of Western Ont. Library, Regional Coll. (London), Middlesex County, Surrogate Court, reg. of wills, no.3810 (mfm. at AO). Christian Guardian, 12 June 1901: 11, 14. A. J. Austin, Saving China: Canadian missionaries in the Middle Kingdom, 1888–1959 (Toronto, 1986). A. J. Broomhall, Hudson Taylor & China’s open century . . . (7v., Seven-oaks, Eng., 1981–89), 7. Reuben Butchart, The Disciples of Christ in Canada since 1830, their origins, faith and practice . . . (Toronto, 1949). China’s Millions (Toronto), September 1893: 128 (copy in Overseas Missionary Fellowship Arch.). Ruth Compton Brouwer, New women for God: Canadian Presbyterian women and India missions, 1876–1914 (Toronto, 1990), 72. Directory, London, Ont., 1888/89: 111; 1893: 496. J. W. Grant, A profusion of spires: religion in nineteenth-century Ontario (Toronto, 1988), 187. Carlotta Hacker, The indomitable lady doctors (Toronto, 1974). S. [A.] Hedin, Through Asia (2v., London, 1898), 2: 1173–77. Peter Hopkirk, Trespassers on the roof of the world: the race for Lhasa (London, 1982). Methodist Magazine and Rev. (Toronto and Halifax), 49 (January–June 1899): 383; 58 (July–December 1903): 276. Missionary Outlook (Toronto), 17 (1899): 365. Trinity College, Calendar (Toronto), 1884–89; Yearbook (Toronto), 1899–1900 (copies in Trinity College Arch., Toronto).

Alvyn J. Austin, “CARSON, SUSANNA (Rijnhart; Moyes),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carson_susanna_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/carson_susanna_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alvyn J. Austin |

| Title of Article: | CARSON, SUSANNA (Rijnhart; Moyes) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |