Source: Link

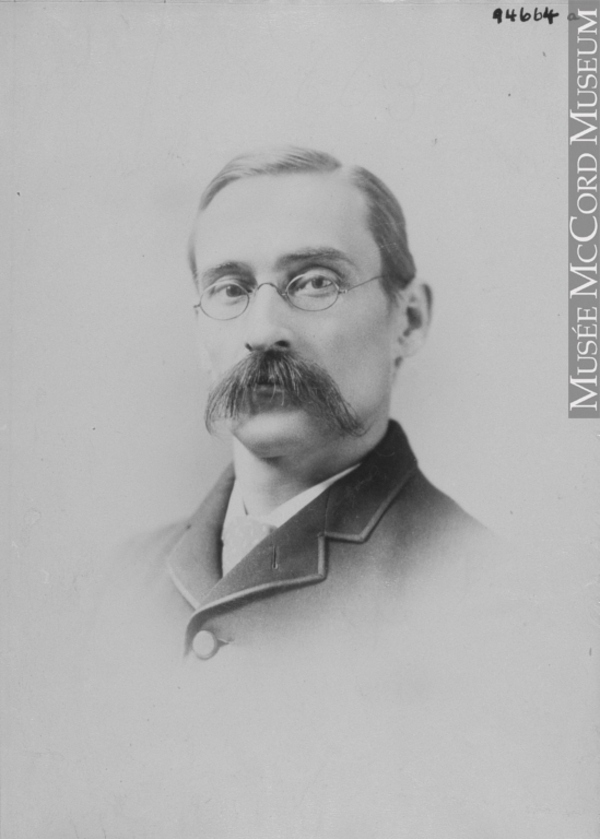

BURGESS, THOMAS JOSEPH WORKMAN, physician, botanist, asylum superintendent, professor, and author; b. 11 March 1849 in Toronto, son of Thomas Burgess, a merchant tailor, and Jane Rigg, both from Carlisle, England; m. 15 April 1875 Jessie McPherson in Toronto, and they had four daughters; d. 18 Jan. 1926 in Montreal and was buried 20 January in Toronto.

Thomas Joseph Workman Burgess attended Upper Canada College in Toronto from 1862 to 1866 and then completed his medical studies at the University of Toronto. Awarded the Starr gold medal by the faculty of medicine, and the first silver medal by the university, he graduated in 1870. He immediately joined the medical staff of the Asylum for the Insane in Toronto, which was under the direction of his godfather and mentor, the renowned Joseph Workman*. In 1872 he accepted a position as surgeon for the international commission responsible for determining the Canadian-American boundary from Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains [see Samuel Anderson*]. Travelling widely throughout Canada in this capacity, he developed an interest in botany, a subject to which he would devote many articles and lectures.

From 1875 to 1887 Burgess worked at the Asylum for the Insane in London, Ont., initially as assistant physician and then as assistant superintendent. Following a dispute with superintendent Richard Maurice Bucke*, he was transferred in 1887 to the Asylum for the Insane in Hamilton, where he was assistant superintendent until 1890. While in Hamilton he participated as a botanist in the activities of the Hamilton Association, serving as vice-president from 1888 to 1890. In May 1890 he became the first medical superintendent of the Protestant Hospital for the Insane in Verdun, Que. During his 33 years in this post, the number of patients in the hospital increased from 139 to 800.

From the very beginning Burgess saw to it that patients in this new institution were treated in the most humane manner, as the annual reports he wrote from 1891 to 1923 show. Although he considered insanity a somatic disease, he had doubts about the effectiveness of medication alone and therefore concentrated his efforts on mental treatment. Opposed to all forms of physical restraint for mental patients, he instead set up an extensive program to keep them occupied (work, physical activity, and leisure pursuits), a practice he had had an opportunity to observe at the London asylum under Bucke’s leadership. In his 1896 annual report Burgess noted that 66 per cent of the patients were engaged in some occupation. From 1901 he also encouraged the admission of private patients (who paid to enter the asylum and who were not subject to the same administrative constraints as public patients in the matter of being discharged) and he declared himself in favour of trial releases for patients who were not fully cured but whose mental health had improved. In 1903 he began implementing an “open-door policy,” leaving the patients’ dormitories unlocked and letting those whose condition allowed it to move about freely and unsupervised within the asylum. In addition, he organized many outings for them and encouraged the public to attend the social evenings held at the asylum. From time to time there were patients who took advantage of such opportunities to run away, but experience showed that they usually came back to the asylum of their own accord after a few days.

Although such reforms were being promoted at the same time by the superintendents of the Asile de Beauport and the Hôpital Saint-Jean-de-Dieu, Burgess had enjoyed much more favourable circumstances for putting them into practice. Unlike the French-speaking asylums, the one in Verdun benefited from the financial support of the wealthy families in Montreal’s English-speaking community. In 1892, for example, a gift from John Henry Robinson Molson made possible the construction of a gymnasium, bowling alley, and curling rink. Through the generosity of George Bull Burland, in 1898 a pathology laboratory was built which Andrew Macphail* directed. In 1900 and 1910 the many donations of Dr James Douglas of New York, whose father had founded the Asile de Beauport [see James Douglas*], made possible the purchase of the land on which the nurses’ residence and the recreational centre known as Douglas Hall were erected.

In return for their gifts, donors were permitted to sit on the institution’s board of directors. This modus operandi had been conceived initially by Alfred Perry, who had collaborated with Cléophée Têtu*, named Thérèse de Jésus, in founding the Asile de Longue-Pointe. The board of directors gave Burgess full authority in the treatment of patients and the hiring of staff. He nonetheless experienced disappointments. He always found it very difficult to retain his most competent assistants and employees because of their heavy workloads and modest salaries. He was also faced with the problem of overpopulation in his hospital. During the first decade of the century, like many alienists of the time, Burgess identified heredity as the principal cause of the increased incidence of mental illness and he was drawn to eugenics. In his 1907 report, for instance, he suggested that the Quebec provincial government, like some American states, should forbid the marriage of carriers of defects considered hereditary, or should introduce compulsory sterilization of alcoholics and other “degenerates.” After noticing in 1905 that nearly 40 per cent of the patients admitted to the Protestant Hospital for the Insane in Verdun had not been born in Canada, he took a clear stand in favour of greater control over immigration. Following the enactment of more restrictive immigration laws in 1906 and 1910, Burgess annually listed numerous mental patients whom he considered candidates for deportation.

Burgess also devoted a great deal of time to promoting psychiatry as a medical specialty. In 1893 he gave a series of lectures on mental illnesses at McGill University (where he would become a full professor in 1899). He also undertook some research into mental diseases, with the help of Dr Macphail and his assistants, including an experimental study in 1895 on the treatment of mental deficiency by the use of thyroid extracts. In 1901 he would try to establish a link between epilepsy and glycosuria. These studies did not lead to conclusive results, however. In 1896 he set up a training school for nurses at the Verdun asylum, where he also taught, as did the rest of the institution’s medical staff. That year he was honorary secretary of a section on nervous and mental illnesses and medical case-law at a pan-American medical congress held in Mexico City. In 1898, to advance their specialty, some 20 alienists from the province of Quebec came together to form the Société Médico-Psychologique de Québec. Burgess was its first vice-president and became its president in 1899. Completely at ease with his French-speaking colleagues and fluent in their language, he encouraged them to establish ties with other North American alienists. He undertook in June 1902 the task of organizing the meeting of the American Medico-Psychological Association, which was held in Montreal. In 1904-5 he became the third Canadian – after Daniel Clark* in 1891-92 (when the association was called the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane) and Bucke in 1897-98 – to serve as president of this organization, which was the forerunner of the current American Psychiatric Association. In 1918 he was a member of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene, whose objectives were to identify the various segments of the population that showed a high risk of mental illness, to organize research on the functioning of the brain and nervous system, and to conduct public information campaigns about insanity and ways of avoiding it.

Credited with being the first to devote himself to the history of psychiatric institutions in Canada, Burgess gave a lecture on this subject to the Royal Society of Canada in 1898. In 1913 the American Medico-Psychological Association delegated him to write the Canadian section of a book entitled The institutional care of the insane in the United States and Canada, which was published in Baltimore, Md, in 1916 and 1917.

Burgess was active in many learned societies, both in Canada and in other countries. He became a member in 1885 of the Royal Society of Canada and in 1886 of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and he took advantage of these forums to publicize his work on Canadian flora. By the beginning of the 1880s Burgess was a regular contributor to the American journal Botanical Gazette, whose pages described the rare plants he had discovered in the course of his travels with botanist John Macoun* in southern Ontario and Nova Scotia. In the fifth volume of Macoun’s Catalogue of Canadian plants, Burgess wrote the sections on ferns. He also took part in meetings of the Canadian Medical Association and the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

By establishing ties with the academic world and serving as an intermediary between the French-speaking alienists of Quebec and their English-speaking colleagues in the rest of North America, Thomas Joseph Workman Burgess made an important contribution to the institutionalization of psychiatry at the beginning of the 20th century. As superintendent of the Protestant Hospital for the Insane, he tried to break down the barriers around the asylum by creating interaction between it and the outside world. Such opening up was quite typical of the life and work of this prolific author, a man active in numerous organizations and interested in many different fields of endeavour.

Thomas Joseph Workman Burgess assisted in the preparation of H. M. Hurd et al., The institutional care of the insane in the United States and Canada, ed. H. M. Hurd (4v., Baltimore, Md, 1916-17; repr. New York, 1973). He also prepared several entries for John Macoun, Catalogue of Canadian plants (7v., Montreal, 1883-1902), 5 (Acrogens, 1890): 253-87. He published a large number of articles in scientific journals and newspapers. For the Hamilton Assoc., Journal and Proc. ([Hamilton, Ont.]), he contributed: “How to study botany” (no.4 (1886-88): 27-53); “Orchids” (pp.113-16); “Notes on the history of botany” (pp.116-17); “Notes on the flora of the forty ninth parallel, from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains” (pp.117-20); “The Lake Erie shore as a botanizing ground” (no.5 (1888-89): 41-59); and “Notes on the genus Rhus” (no.8 (1891-92): 119-30). In the Montreal Medical Journal he published “Thyroid feeding and its application to the treatment of insanity” (24 (1895-96): 842-52); “A compendium of insanity” (27 (1898): 549-50); “Two cases of ephemeral mania, uncomplicated with epilepsy, intemperance or parturition” (28 (1899): 938-41; also published in French in L’Union médicale du Canada (Montréal), 28 (1899): 715-20); “The insane in Canada; presidential address: American Medico-Psychological Association, San Antonio, Texas, April 18th, 1905” (34 (1905): 399-430; also published in the American Journal of Insanity (Baltimore), 62 (1905-6): 1-36); and “The family physician and the insane” (36 (1907): 100-17). His articles in the Botanical Gazette (Crawfordsville and Logansport, Ind.) include: “Notes from Canada” (7 (1882): 95-96); “Trifolium hybridum, L.” (p.135); “A botanical holiday in Nova Scotia” (9 (1884): 1-6, 19-23, 40-45, 56-59); and “Aspidium Oreopteris Swz.” (11 (1886): 63). Burgess also published: “Art in the sick room,” Times (Hamilton), 5 Jan. 1889; “Canadian Filicineæ,” RSC, Trans., 1st ser., 2 (1884), sect.iv: 163-226 (with John Macoun); “A historical sketch of our Canadian institutions for the insane,” RSC, Trans., 2nd ser., 4 (1898), sect.iv: 3-122; “On the beneficient and toxical effects of the various species of Rhus,” Canadian Journal of Medical Science (Toronto), 5 (1880): 327-34; “Polypus of the heart,” Canadian Journal of Medical Science, 4 (1879): 139-40; and “Recent additions to Canadian Filicineæ, with new stations for some of the species previously recorded,” RSC, Trans., 1st ser., 4 (1886), sect.iv: 9-18.

AO, RG 80-5-0-54, no.11075. LAC, RG 31, C1, 1871, Toronto, St David’s Ward, div.4: 8; 1891, Verdun, Que. Gazette (Montreal), 19 Jan. 1926. Montreal Daily Star, 19 Jan. 1926. La Presse, 20 janv. 1926. C. H. Cahn, Douglas Hospital: 100 years of history and progress (Verdun, 1981). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Canadian who’s who, 1910. Directory, Montreal, 1908-10. Denis Goulet et André Paradis, Trois siècles d’histoire médicale au Québec; chronologie des institutions et des pratiques (1639-1939) (Montréal, 1992). Guy Grenier, “L’implantation et les applications de la doctrine de la dégénérescence dans le champ de la médecine et de l’hygiène mentales au Québec entre 1885 et 1930” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Montréal, 1990). John Macoun, Autobiography of John Macoun, m.a. . . . , intro. E. T. Seton ([Ottawa], 1922). André Paradis, “Thomas J. W. Burgess et l’administration du Verdun Protestant Hospital for the Insane (1890-1916),” Canadian Bull. of Medical Hist. (Waterloo, Ont.), 14 (1997): 5-35. Protestant Hospital for the Insane, Annual report (Verdun), 1891-1923. The roll of pupils of Upper Canada College, Toronto, January, 1830, to June, 1916, ed. A. H. Young (Kingston, Ont., 1917), 145. S. E. D. Shortt, Victorian lunacy: Richard M. Bucke and the practice of late nineteenth-century psychiatry (Cambridge, Eng., 1986).

Guy Grenier, “BURGESS, THOMAS JOSEPH WORKMAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burgess_thomas_joseph_workman_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/burgess_thomas_joseph_workman_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Guy Grenier |

| Title of Article: | BURGESS, THOMAS JOSEPH WORKMAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |