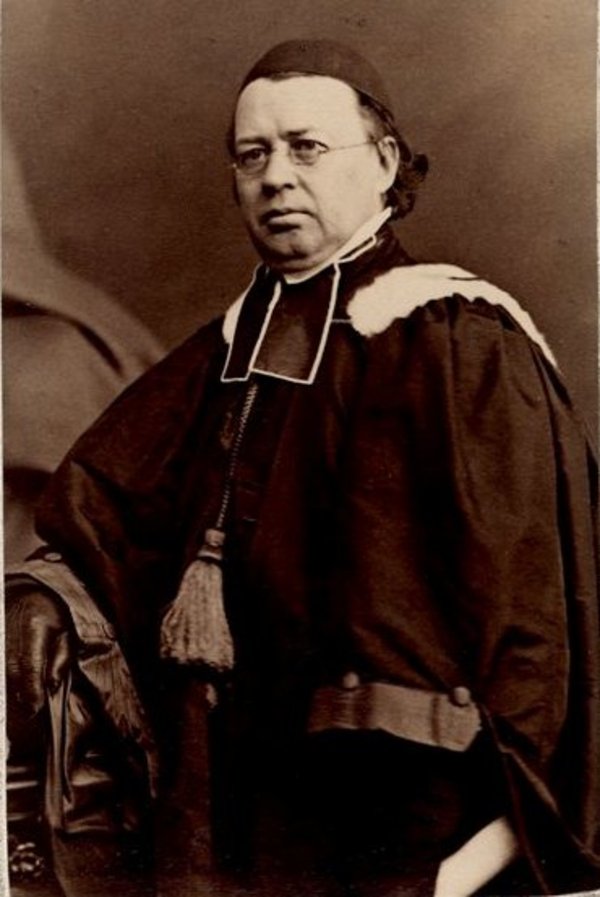

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BRUNET, LOUIS-OVIDE, priest, botanist; b. 10 March 1826 at Quebec, son of Jean-Olivier Brunet, merchant, and Cécile Lagueux; d. 2 Oct. 1876 at Quebec.

In 1835 Louis-Ovide Brunet entered grade viii at the Petit Séminaire of Quebec; Octave Crémazie was one of his fellow-pupils. Abbé Edward John Horan, the future bishop of Kingston (Ontario), introduced him to natural history. Brunet spent part of his holidays with his uncle, the notary Louis-Édouard Glackmeyer*, an ardent collector of plants, who was assembling a herbarium. Brunet entered the seminary in 1844, and was ordained priest on 10 Oct. 1848; after being a missionary for two years at Grosse Île, he was a curate from 1848 to 1851 and again in 1853 and 1854, and was parish priest of Saint-Lambert-de-Lévis from 1854 to 1858.

When in 1856 Abbé Horan was appointed principal of the École Normale Laval at Quebec, his post of professor at the seminary and at the young Université Laval became vacant. In considering a replacement, the names of Abbé Léon Provancher* and Louis-Ovide Brunet came up; they had not as yet published anything, but were actively engaged in botanical pursuits and each was preparing a description of Canadian flora. Brunet was chosen. From 1858 to 1861 he devoted himself at the seminary to the teaching of botany, at the same time giving a course in dogma to the theology students. In 1862, the mineralogist Thomas Sterry Hunt* having left the Université Laval for McGill, Brunet succeeded him in the chair of natural history, which he occupied from 1863 to 1871. He was appointed titular professor in 1865.

Meanwhile, according to Georg August Pritzel, Brunet had published a short paper on Canadian woods (1857), and a first study (1861) on the voyage of the botanist André Michaux* in the direction of Hudson Bay in 1792. The latter’s diary being at that time unpublished – it was not published until 1888 – Brunet worked with fragmentary notes, whose deficiencies no doubt explain errors of interpretation in his text.

His botanical excursions at Petit Cap (Montmorency County), near Cap Tourmente, enabled him to meet Abbé Léon Provancher, at that time parish priest of Saint-Joachim. In 1861 they made botanical expeditions to various places: Petit Cap, Île d’Orléans, Saguenay, and Lac Saint-Jean. Between them there soon developed a stubborn enmity, of which their correspondence and writings preserve traces: it reached the point of Brunet’s refusing to contribute to the Naturaliste canadien, which was owned by Provancher. In 1860 the professor of the Université Laval had gone to Niagara on his first journey in Upper Canada. The following year, alone, or with T. S. Hunt or Abbé Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland*, he gathered more specimens at Quebec, Montreal, Saint-Hyacinthe, Drummondville, in Lotbinière County and along the Rivière Sainte-Anne.

A plan was put forward at this time to set up a botanical garden at Quebec under the auspices of the seminary, with the collaboration of the municipality and the government. To prepare himself for the task of future director of this undertaking, Brunet travelled in Europe for a year (1861–62), associating with botanists of repute, visiting Regent’s Park in London, the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, the botanical gardens of Liverpool, Kew, Montpellier, Florence, Pisa, Rome, Brussels, Louvain, Bonn, Düsseldorf, Utrecht, Amsterdam, Leyden, Rotterdam, and a Danish nursery.

At the Sorbonne, Brunet attended the lectures of Pierre-Étienne-Simon Duchartre, and at the Jardin des Plantes those of Adolphe-Théodore Brongniart and of Joseph Decaisne. With the latter he visited the gardens of Nantes and Angers, and again Kew Gardens. At the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, where he worked freely, in the company of some remarkable scientists, he undertook a study of the Canadian plants of Michaux, which were preserved in the herbarium of that institution, and of the Canadian species mentioned in the Canadensium plantarum . . . historia, by Jacques-Philippe Cornut. The identification of these species was assuredly a valuable help to Abbé Joseph-Clovis Kemner* Laflamme, his pupil and then his successor, when the latter presented a communication on this work to the Royal Society of Canada.

Once back in Quebec, Brunet resumed his teaching and research. He went to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington in 1864, and Anticosti Island and the Strait of Belle-Isle in mid-summer 1865. And according to his travel diaries, he was on botanical expeditions in 1866 at Ottawa, London, Belleville, Hamilton, Brockville, Chatham, and Newbury in Canada West, and at Montreal, Trois-Rivières, Rimouski, and Rivière-du-Loup in Canada East.

Before his return from Europe, Brunet had already begun to prepare a study on the flora of Canada. The notes he amassed from 1860 to 1866 cover 582 pages, and have remained unpublished, no doubt because in 1862 Léon Provancher published his Flore canadienne. In a letter to Asa Gray, Brunet deemed the publication of his rival’s work to be too hasty. Other manuscripts of Brunet would be worthy of publication if they were accompanied by the commentaries of a sagacious botanist. The only work on flora that Brunet published, Éléments de botanique et de physiologie végétale . . . (1870), deserved a better fate. But Provancher’s Flore, and the Sulpician Jean Moyen’s Cours élémentaire de botanique . . . published in 1871 at Montreal, stole the market from him. Brunet’s work comprises numerous accounts of what he had observed, lists of popular names, and the description of five botanical entities new to the science. Several vegetable species will recall to botanists the active life of this man that was too early cut off, in particular the Crataegus brunetiana Charles Sprague Sargent and the Astragalus brunetianus (Merritt Lyndon Fernald) Jacques Rousseau*.

Apart from his courses, his publications, the founding in 1862 and the organization of the herbarium of the Université Laval, Brunet prepared collections of Canadian woods for exhibitions in Dublin (1865) and Paris (1867). The plan for a botanical garden at Quebec absorbed part of his energies from 1861 to 1870. In the latter year he thought of creating a school of forestry, in reality simply an arboretum, for want of a more elaborate undertaking. This project, like that of the botanical garden, did not come to fruition: the seminary struck it off its programme in 1879.

In 1870 the government of Quebec invited the Université Laval to give a course in applied sciences and offered to subsidize it. Entrusted to Louis-Ovide Brunet and Dr François-Alexandre-Hubert La Rue*, the course began, but after a few lessons the rector of the university, fearing that politics would push its way in, terminated the project.

At the age of 44, a sick man, disappointed by repeated failure to achieve success, Louis-Ovide Brunet retired to the home of his mother and sister, where he lived until his death. Self-taught, like all scientists in Quebec before 1920, Louis-Ovide Brunet none the less proved to be the best French Canadian botanist of the last century. His contemporaries, who lacked the necessary training to judge him, were not capable of seeing in him the scientist who might have brought great lustre to his milieu. Working with minute care and unobtrusively, he was not one of those who seek to be first at all costs in the field of publishing. Furthermore, as Brunet did not receive the necessary encouragement, the major part of his work, and the most interesting, remains unpublished.

[L.-O. Brunet, Catalogue des plantes canadiennes contenues dans l’herbier de l’université Laval et recueillies pendant les années 1858–1865 (Québec, 1865) (The complete catalogue was to contain more than 200 pages and several plates; however, only the first section was published. The four plates cited by Brunet do not appear in the copies which were consulted; were they ever published?); Catalogue des végétaux ligneux du Canada pour servir à l’intelligence des collections de bois économiques envoyées à l’exposition universelle de Paris, 1867 (Québec, 1867); Éléments de botanique et de physiologie végétale, suivis d’une petite flore simple et facile pour aider à découvrir les noms des plantes les plus communes au Canada (Québec, 1870); Énumération des genres de plantes de la flore du Canada précédée des tableaux analytiques des familles . . . (Québec, 1864); Histoire des Picea qui se rencontrent dans les limites du Canada (Québec, 1866); [ ], “Journal de voyage en Europe de l’abbé Ovide Brunet en 1861–1862,” Arthur Maheux, édit., Le Canada français (Québec), 2e sér., XXVI (1938–39), 591–99, 681–90, 783–90, 886–92, 983–87; [ ], Manière de préparer les plantes et autres objets de musée (n.p., n.d.); “Michaux and his journey in Canada,” The Canadian Naturalist and Geologist (Montreal), new ser., I (1864), 325–37; “Notes sur les plantes recueillies en 1858, par M. l’abbé Ferland sur les côtes du Labrador, baignées par les eaux du Saint-Laurent,” La littérature canadienne de 1850 à 1860 (2v., Québec, 1863), I, 367–74; Notice sur le musée botanique de l’université Laval . . . (Québec, 1867); Notice sur les plantes de Michaux et sur son voyage au Canada et à la baie d’Hudson, d’après son journal manuscrit et autres documents (Québec, 1863); “On the Canadian species of the genus Picea,” Canadian Naturalist and Geologist (Montreal), new ser., III (1868), 102–10; Voyage d’André Michaux en Canada, depuis le lac Champlain jusqu’à la baie d’Hudson (Québec, 1861). j.r.]

Frère Marie-Victorin [Conrad Kirouac], Flore laurentienne (1re éd., Montréal, 1935), 15, 308, 356. Jacques Rousseau, Les Astragalus du Québec et leurs alliés immédiats (Contributions du laboratoire de botanique de l’Université de Montréal, 24, New York, Montréal, Leipzig, 1933). Arthur Maheux, “Louis-Ovide Brunet, botaniste, 1826–1876,” Le Naturaliste canadien (Québec), LXXXVII (1960), 5–22, 53–57, 120–48, 149–64, 228–36, 253–68, 277–86; LXXXVIII (1961), 78–83, 149–60, 324–36; LXXXIX (1962), 265–78. Jacques Rousseau, “Les entités botaniques nouvelles créées par Brunet,” Le Naturaliste canadien (Québec), LVII (1930), 132–35; “Provancher et la publication des Éléments de botanique de Brunet (accompagné d’une lettre inédite),” Le Naturaliste canadien (Québec), LVII (1930), 196–202; “Un travail de l’abbé Brunet,” Le Naturaliste canadien (Québec), LVIII (1931), 69; “Un travail oublié de l’abbé Ovide Brunet,” Le Naturaliste canadien (Québec), LXVII (1940), 200; “Le voyage d’Asa Gray à Québec en 1858 (lettres inédites),” Le Naturaliste canadien (Québec), LVII (1930), 202–4. Jacques Rousseau et Bernard Boivin, “La contribution à la science de la Flore canadienne de Provancher,” Le Naturaliste canadien (Québec), 95 (1968), 1499–530.

Jacques Rousseau, “BRUNET, LOUIS-OVIDE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 2, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brunet_louis_ovide_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brunet_louis_ovide_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jacques Rousseau |

| Title of Article: | BRUNET, LOUIS-OVIDE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 2, 2024 |