Source: Link

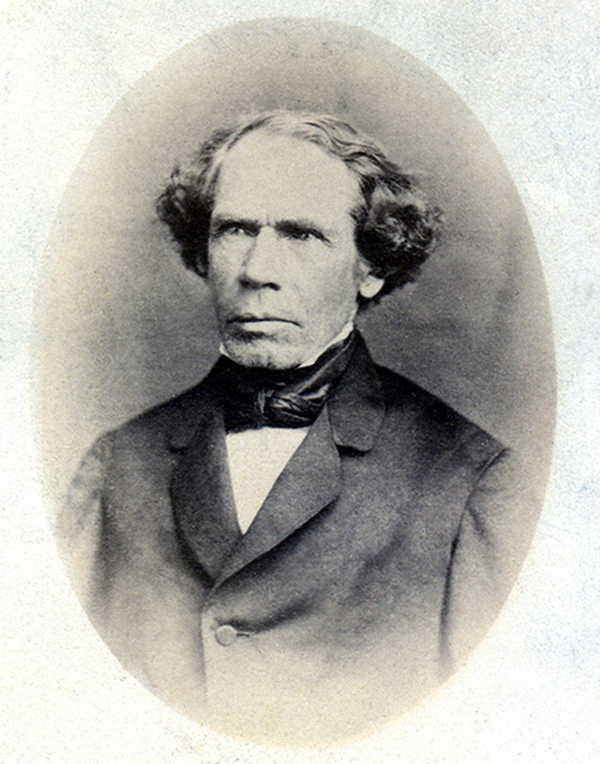

BOURGEAU (Bourgeault), VICTOR, joiner, carpenter, woodcarver, and architect; b. 26 Sept. 1809 at Lavaltrie, Lower Canada, son of Basile Bourgeault, a master wheelwright, and Marie Lavoie; d. 1 March 1888 in Montreal, Que.

Victor Bourgeau seems to have begun working in his father’s business at an early age. During the 1820s he was employed at building sites in the region around Lavaltrie, as an apprentice joiner and carpenter to his uncle (also Victor Bourgeau). Little is known about his upbringing. When he married Edwidge Vaillant on 17 June 1835 he could not sign the register and his biographers attribute his lack of schooling to the precarious financial position of his father.

In the 1830s an event known by oral tradition, and recorded by his biographers, is believed to have changed the course of his career. Now an accomplished craftsman, Bourgeau is said to have met in Montreal the Italian painter Angelo Pienovi*, who being penniless offered to teach him the techniques of draughtsmanship. Although this story cannot be verified, something significant must have happened at this period because subsequently Bourgeau appears literate and skilled in draughting.

His first known works were executed in 1839 at Boucherville, where he received payment for the completion of altar carvings and other embellishments. These were unfortunately destroyed when the church of Sainte-Famille burned down in 1843. The craftsman, who still called himself a joiner and woodcarver, completed several projects for the church of Notre-Dame in Montreal, including a pulpit which was much lauded by his contemporaries and was described by his biographers as “a little masterpiece of elegance and strength.”

Bourgeau entered seriously upon his long and fruitful career as an architect after 1847. He had come to Montreal in the 1830s in time to witness important architectural developments, which were increasingly influenced by neo-classical and neo-Gothic styles; it was the architect John Ostell* who, along with James O’Donnell*, John Wells, and William Footner, perhaps exemplified this trend most strongly and who in the 1840s exercised a preponderant influence. Several facts suggest that Bourgeau received his training under Ostell. Since the kind of work carried out by Ostell required numerous assistants it is likely that Bourgeau went to work as a trainee. This was the only way to enter the profession at that time; moreover, Ostell was his immediate predecessor in the field of religious architecture. After 1850 Bourgeau finished some of the work undertaken by Ostell, who had embarked on a business career, and took over his responsibilities in relation to the diocese and the religious communities. In addition, Bourgeau maintained a stylistic continuity, as his first architectural works demonstrate.

In 1849, when he was beginning to establish himself as an architect, the important project of enlarging the church of Sainte-Anne at Varennes gave Bourgeau an opportunity to display the general conformity to architectural tradition which was one characteristic of his art. Indeed, in commencing the enlargement of the nave between the towers and chapels, he reverted to a method of alteration which had been used in 1734 at Notre-Dame in Montreal. This type of modification was undoubtedly calculated to demonstrate that he was a practical architect thoroughly familiar with sensible, tested solutions. In 1850 the parish council of Sainte-Rose (now in the city of Laval) commissioned Bourgeau to build a new church. Here again, true to his architectural heritage, he constructed a neoclassical façade modelled on the church of Sainte-Geneviève at Pierrefonds, which had been designed by Thomas Baillairgé* and erected in 1839. The church at Sainte-Rose, Bourgeau’s first large one, reveals also that he was sufficiently in command of his profession to be able to carry out major commissions and he used a technical approach which made a good impression on those who employed him.

Victor Bourgeau’s success was now assured. He continued to draw up the plans for numerous buildings and to supervise the work on site. Olivier Maurault in Marges d’histoire, and Gérard Morisset* in his inventory of works of art, have already listed a substantial number of his accomplishments, but further detailed research alone will make it possible to do justice to the talent and industry of this prolific architect who, according to a study now in progress, designed some 100 buildings. After the church of Sainte-Rose (1850) Bourgeau prepared the plans for many buildings in which the influence of Thomas Baillairgé is noticeable. The church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul (1857), now in the city of Laval, is an example of this continuation of a late form of neo-classicism. Testimony to the architect’s ability to adapt himself to projects of a more modest scale can be found in the less elaborate churches of the Joliette region: Saint-Alexis (1852); Saint-Félix-de-Valois (1854); L’Assomption-de-la-Sainte-Vierge, in the village of L’Assomption (1863); and Saint-Antoine, at Lavaltrie (1869). All the edifices of this type have two characteristics: a façade on which ornamentation is developed regardless of the structure standing out behind it, and belfries of the usual octagonal or circular design but with two tambours superimposed and topped by a spire. Here we have what might almost be called Victor Bourgeau’s signature. He copied these belfries, as well as some of the façades, from architectural texts. There is an obvious relationship between this type of building and certain edifices by the Americans Benjamin Henry Latrobe and Minard Lafever.

At the same time Bourgeau promoted the development of neo-Gothic architecture. The church of Saint-Pierre-Apôtre in Montreal, built in 1852–53, as well as the cathedrals of L’Assomption at Trois-Rivières, finished in 1858, and Saint-Germain at Rimouski, completed in 1862, are evidence of the architect’s mastery of this new style. Bourgeau’s neo-Gothic works were not, however, original creations, as the obvious affinity of the cathedral at Trois-Rivières with St Luke’s in London makes clear. Bourgeau’s debt to British and American architecture is substantial. His great neo-Gothic achievement remains the restoration of the interior décor of Notre-Dame in Montreal. The plans were submitted in 1857 but the work went on until 1880. Bourgeau set out to modify the building’s appearance, which was deemed too severe, and the interior décor he created in Notre-Dame so well reflected Quebec tastes in architecture that it quickly became a model widely copied throughout the province.

But the use of neo-Gothic architecture inevitably resulted in confusion of Roman Catholic with Protestant churches in the province of Quebec. Indeed, after the earliest phase of this architecture (adopted for the symbolism of forms inherited from a glorious period of western Christian civilization), this structural affinity between the churches of the two religious groups gave rise to a quite violent reaction. In Montreal the Jesuits and Bishop Ignace Bourget advocated a return to classical forms and baroque ornamentation. It was undoubtedly Bourget who led the way, with a plan worked out by 1852 for the reconstruction of the cathedral of Saint-Jacques (now the basilica of Marie-Reine-du-Monde) in Montreal, on the model of the basilica of St Peter’s in Rome. Bourgeau was sent to Rome in 1857 to study and measure St Peter’s, and initially opposed Bourget’s plan because after seeing St Peter’s he did not think it could be copied on a reduced scale. In 1871 the tenacious bishop of Montreal sent Father Joseph Michaud to Rome, and after taking the necessary measurements Michaud prepared a small-scale model. Work began in Montreal in 1875 and Bourgeau agreed to supervise it. The cathedral of Saint-Jacques was consecrated in 1885 but was not finished until 1890. This monument immediately became the symbol of the ultramontane movement and affirmed the supremacy of the neo-baroque style in the Roman Catholic religious architecture of Quebec.

Most of the churches erected by Bourgeau after 1865 were neo-baroque, particularly in their interiors. He followed the simplified model of St Peter’s, with a boldly conceived coffered vault, a nave separated into three aisles by a colonnade, and a simple reredos as an integral part of the architecture, with space for the erection of that pre-eminently baroque feature, a baldachin. The interiors of Saint-Barthélémy (near Berthierville) and L’Assomption-de-la-Sainte-Vierge are two splendid examples of Bourgeau’s architectural skill.

Bourgeau was also actively engaged in convent architecture. The convent of the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général of Montreal (Grey Nuns), which led to some controversy (it was threatened with demolition in the 1970s), was built between 1869 and 1871 according to the plans of Bourgeau and his partner, Alcibiade Leprohon; they followed the main lines of the traditional architecture preserved in the religious communities, except for the façades to which they added a facing of rough-surfaced stone and openings framed in cut stone. The chapel, built between 1874 and 1878, has elements of Romanesque style. Elsewhere, as in the Hôtel-Dieu in Montreal, Bourgeau more directly adopted the neo-baroque style, particularly when he built the cupola over the chapel.

The Bourgeau-Leprohon partnership seems to have attracted a greater diversity of business. The partnership was formed about 1870, at the time when work was beginning on the convent of the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général. The firm was subsequently commissioned to construct a number of buildings which are clearly more eclectic, in particular such commercial buildings as the hotel near the Bonsecours market, erected in 1861, and the examining warehouse in Montreal put up in 1875. One of Bourgeau’s last important achievements was the preparation in about 1885 of the plans for the Canadian College in Rome, a building valued then at $200,000.

Bourgeau died on 1 March 1888 while on his way to make a business call on the Sisters of Charity; he was 78. He had lost his first wife in 1877, and also his two children, one having died in infancy and the other when he was a young lawyer. On 4 May 1878 at Montreal he had married Delphine Viau. His contemporaries remembered “old Bourgeau” as a demanding and relentless worker who had become a legend at the building sites he inspected, invariably sporting a top hat. His work, neglected in the midst of the vast productive activity of the latter half of the 19th century, is just beginning to be rediscovered and appreciated. It would, however, be a mistake to try to distinguish it too sharply from that of his contemporaries. His diversified and important contribution can be understood only in the context of his period and of the architectural climate of the 19th century.

AP, Saint-Antoine (Lavaltrie), Reg. des baptêmes, mariages et sépultures, 26 sept. 1809. IBC, Centre de documentation, Fonds Morisset, 2, B772.5/V64/1; 085/3/J65.5. La Minerve, 11 févr. 1857, 22 mars 1888. Dominion annual register, 1885: 217–18. M. A. Coyle, “Victor Bourgeau (1809–1888), architect: a biographical sketch” (paper presented at McGill Univ., Montreal, 1960). J.-C. Marsan, Montréal en évolution; historique du développement de l’architecture et de l’environnement montréalais (Montréal, 1974). Olivier Maurault, Marges d’histoire; l’art au Canada ([Montréal], 1929), 220–23; La paroisse; histoire de l’église Notre-Dame de Montréal (Montréal et New York, 1929); Saint-Jacques de Montréal; l’église, la paroisse (Montréal, 1923), 54–55. Luc Noppen, Les églises du Québec (1600–1850) (n.p., 1977). Qué., Ministère des Affaires culturelles, “Église de Sainte-Rose . . . histoire, relevé et analyse” (Québec, 1974). Barbara Salomon de Friedberg, Le domaine des sœurs grises, boulevard Dorchester, Montréal (Québec, 1975). Franklin Toker, The Church of Notre-Dame; an architectural history (Montreal and London, Ont., 1970). John Bland, “Deux architectes du XIXe siècle,” Architecture, Bâtiment, Construction (Montréal), 8 (juillet 1953): 20. G. Ducharme, “La maquette de la cathédrale de Montréal (œuvre du père Joseph Michaud, clerc de Saint-Viateur),” Technique (Montréal), 15 (février 1941): 85–91. A.-C. Dugas, “Le plan miniature de la cathédrale de Montréal et le R. P. Michaud, C.S.V., “L’Action populaire (Joliette, Qué.), 7 juin 1923: 3. Alan Gowans, “From Baroque to Neo-Baroque in the church architecture of Quebec,” Culture (Québec), 9 (1949): 140–50. Olivier Maurault, “L’architecte Victor Bourgeau”, BRH, 29 (1923): 306–7; “Projets de décoration de Notre-Dame,” Vie des arts (Montréal), 9 (Noël 1957): 12–13. Gérard Morisset, “L’architecte Victor Bourgeau,” La Patrie, 7 mai 1950: 26–27. Noël Paquette, “Le père Joseph Michaud C.S.V., architecte de la cathédrale de Montréal,” L’Estudiant (Joliette), 6 (mai–juin 1942): 20–21. Émile Venne, “Victor Bourgeault, architecte (1809–1888),” L’Ordre (Montréal), 22, 23 mars 1935.

Luc Noppen, “BOURGEAU (Bourgeault), VICTOR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 28, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourgeau_victor_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourgeau_victor_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Luc Noppen |

| Title of Article: | BOURGEAU (Bourgeault), VICTOR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | November 28, 2024 |